Explaining Corporate Success Abstract

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Beecham Group PLC and Another V Triomed (Pty) Ltd [2002] 4 All SA 193 (SCA)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9907/beecham-group-plc-and-another-v-triomed-pty-ltd-2002-4-all-sa-193-sca-369907.webp)

Beecham Group PLC and Another V Triomed (Pty) Ltd [2002] 4 All SA 193 (SCA)

Beecham Group PLC and another v Triomed (Pty) Ltd [2002] 4 All SA 193 (SCA) Division: Supreme Court of Appeal Date: 19 September 2002 Case No: 100/01 Before: Harms, Scott, Mpati, Conradie JJA and Jones AJA Sourced by: PR Cronje Summarised by: D.Harris Parallel Citation: 2003 (3) SA 639 (SCA) . Editor's Summary . Cases Referred to . Judgment . [1] Intellectual property Trade marks Registration of shape as trade mark Where shape is not intended to be used to distinguish owner's products from those of another, it cannot be regarded as a trade mark Application for expungement from trade marks register therefore allowed. Editor's Summary Both parties involved in the present matter were players in the pharmaceutical industry. The Appellants sought the upholding of a trade mark for the shape of a tablet, and a finding that the Respondent had infringed the trade mark. The Respondent imported a tablet with the same composition and shape as that of the Appellants. In the court a quo, the Respondent applied for the expungement from the trade mark register of the shape trade mark. The Appellants launched a counterapplication for relief for trade mark infringement. The latter application failed while that of the Respondent succeeded. Held Interested parties may apply to court for the removal of an entry wrongly made or remaining on the trade mark register. The first question posed by the Court was whether the Appellants' shape mark constituted a trade mark in terms of section 10(1) of the Trade Marks Act 194 of 1993 ("the Act"). -

Glaxosmithkline Plc Annual Report for the Year Ended 31St December 2000

GlaxoSmithKline 01 GlaxoSmithKline plc Annual Report for the year ended 31st December 2000 Contents Report of the Directors 02 Financial summary 03 Joint statement by the Chairman and the Chief Executive Officer 05 Description of business 29 Corporate governance 37 Remuneration report 47 Operating and financial review and prospects 69 Financial statements 70 Directors’ statements of responsibility 71 Report by the auditors 72 Consolidated statement of profit and loss 72 Consolidated statement of total recognised gains and losses 74 Consolidated statement of cash flow 76 Consolidated balance sheet 76 Reconciliation of movements in equity shareholders’ funds 77 Company balance sheet 78 Notes to the financial statements 136 Group companies 142 Principal financial statements in US$ 144 Financial record 153 Investor information 154 Shareholder return 156 Taxation information for shareholders 157 Shareholder information 158 Share capital 160 Cross reference to Form 20-F 162 Glossary of terms The Annual Report was approved by the Board 163 Index of Directors on 22nd March 2001 and published on 12th April 2001. Contact details 02 GlaxoSmithKline Financial summary 2000 1999 Increase Business performance £m £m CER % £ % Sales 18,079 16,164 9 12 Trading profit 5,026 4,378 12 15 Profit before taxation 5,327 4,708 11 13 Earnings/Net income 3,697 3,222 13 15 Earnings per Ordinary Share 61.0p 52.7p 14 16 Total results Profit before taxation 6,029 4,236 Earnings/Net income 4,154 2,859 Earnings per Ordinary Share 68.5p 46.7p Business performance: results exclude merger items and restructuring costs; 1999 sales and trading profit exclude the Healthcare Services businesses which were disposed of in 1999. -

Government Gazette Republic of Namibia

GOVERNMENT GAZETTE OF THE REPUBLIC OF NAMIBIA N$16.68 WINDHOEK- 2 September 1996 No. 1396 CONTENTS TRADE MARKS .............................................................................................................................. APPLICATIONS FOR REGISTRATION OF TRADE MARKS IN NAMIBIA (Applications accepted in terms of Act No. 48 of 1973) '\ Any person who has grounds for objection to any of the following trade marks, may, within the prescribed time, lodge Notice of Opposition on form SM6 con tained in the Second Schedule to the Trade Marks Rules in Namibia, 1973. The prescribed time is two months after the date of advertisement. This period may on application be extended by the Registrar. Where the Gazette is issued late, the period of opposition will count as from the date of issue and a notice relating thereto will be displayed on the public notice board in the Trade Marks Registry. Formal opposition should not be lodged until after notice has been given by letter to the applicant for registration so as to afford him an opportunity of withdrawing his application before the expense of preparing the Notice of Opposition is in curred. Failing such notice to the applicant an opponent may not succeed in ob taining an order for costs. "B" preceding the number indicates Part B of the Trade Mark Register. Neither the office mentioned hereunder nor Central Bureau Services (Pty) Ltd., acting on behalf of the Government of Namibia, guarantee the accuracy of this publication or undertake any responsibility for errors or omissions or their conse quences. E.T. KAMBOUA REGISTRAR OF TRADE MARKS FOR NAMIBIA 2 Government Gazette 2 September 1996 No. 1396 TRADE MARKS REMOVED FROM 1 JULY 1992 TO 30 JUNE 1996 NO. -

A Thesis Entitled an Oral Dosage Form of Ceftriaxone Sodium Using Enteric

A Thesis entitled An oral dosage form of ceftriaxone sodium using enteric coated sustained release calcium alginate beads by Darshan Lalwani Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Pharmaceutical Sciences with Industrial Pharmacy Option _________________________________________ Jerry Nesamony, Ph.D., Committee Chair _________________________________________ Sai Hanuman Sagar Boddu, Ph.D, Committee Member _________________________________________ Youssef Sari, Ph.D., Committee Member _________________________________________ Patricia R. Komuniecki, PhD, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2015 Copyright 2015, Darshan Narendra Lalwani This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of An oral dosage form of ceftriaxone sodium using enteric coated sustained release calcium alginate beads by Darshan Lalwani Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science Degree in Pharmaceutical Sciences with Industrial Pharmacy option The University of Toledo May 2015 Purpose: Ceftriaxone (CTZ) is a broad spectrum semisynthetic, third generation cephalosporin antibiotic. It is an acid labile drug belonging to class III of biopharmaceutical classification system (BCS). It can be solvated quickly but suffers from the drawback of poor oral bioavailability owing to its limited permeability through -

Honorary Graduates

Honorary Graduates (Chronological list) The names of deceased graduates are printed in italics. Master of Arts (MA) George Harris Thomson, Secretary-Treasurer of the Royal College of Science and Technology from 1947 to 1964, Registrar of the University from 1964 to 1966 July 1966 Charles Geoffrey Wood, University Librarian March 1967 William B Paton, County Librarian, Lanarkshire - First Head of the Scottish School of Librarianship, Scottish College of Commerce, 1946-50 April 1972 Gustav Heiberg, Chief of Division, Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs July 1975 Charles Stewart, formerly Depute Bursar (Finance) in the University Administration Oct 1975 Louis McGougan, Bursur of the University of Strathclyde March 1976 Duncan Matheson, formerly Director of Physical Education in the University July 1983 Walter Underwood, formerly Planning Consultant to the University July 1983 Zbigniew Byszewski, former Consul-General for Poland in Scotland June 1986 John Turner, Organist to the University and Glasgow Cathedral July 1990 Susan Wighton, who worked as a nurse in Palestinian refugee camps July 1990 Andrew Miller, Director of Libraries, City of Glasgow District Council July 1990 Tommy Orr, former University Security Controller July 1990 James Arnold, Director and Village Manager, Lanark New Town Nov 1990 Graham Douglas, Draughtsman, Royal Commission on Ancient Building and Historical Monuments of Scotland July 1992 Yvonne Carol Grace Murray, Athlete May 1995 Master of Science (MSc) Ronald Ewart Nicoll, Professor of Urban Planning March 1967 -

94771408.Pdf

VSB — TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY OF OSTRAVA FACULTY OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF FINANCE Zhodnocení finanční pozice společnosti GlaxoSmithKline, a.s. Evaluation of Financial Position of the Company GlaxoSmithKline plc. Student: Xinran Chen Supervisor of the bachelor thesis: Ing. Ingrid Petrová, Ph.D. Ostrava 2017 Content 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 2 Description of the Financial Analysis Methodology ........................................................... 6 2.1 Goal of financial analysis ......................................................................................... 6 2.2 Source of data for financial analysis ......................................................................... 7 2.2.1 Balance sheet .................................................................................................. 7 2.2.2 Income statement ............................................................................................ 9 2.2.3 Cash flow statement ..................................................................................... 10 2.3 Common-size analysis ............................................................................................ 12 2.3.1 Vertical common-size analysis ..................................................................... 12 2.3.2 Horizontal common-size analysis ................................................................ 13 2.4 Financial ratio analysis .......................................................................................... -

Other Statutory Disclosures Continued

272 GSK Annual Report 2016 Other statutory disclosures continued Group companies In accordance with Section 409 of the Companies Act 2006 a full list of subsidiaries, associates, joint ventures and joint arrangements, the address of the registered office and effective percentage of equity owned, as at 31 December 2016 are disclosed below. Unless otherwise stated the share capital disclosed comprises ordinary shares which are indirectly held by GlaxoSmithKline plc. The percentage held by class of share is stated where this is less than 100%. Unless otherwise stated, all subsidiary companies have their registered office in their country of incorporation. All subsidiary companies are resident for tax purposes in their country of incorporation unless otherwise stated. Name Security Registered address Wholly owned subsidiaries 1506369 Alberta ULC Common 3500 855-2nd Street SW, Calgary, AB, T2P 4J8, Canada Action Potential Venture Capital Limited Ordinary 980 Great West Road, Brentford, Middlesex, TW8 9GS, England Adechsa GmbH (iv) Ordinary c/o PRV Provides Treuhandgesellschaft AG, Dorfstrasse 38, Baar, 6341, Switzerland Affymax Research Institute Common Corporation Service Company, 2710 Gateway Oaks Drive, Suite 150N, Sacramento, California, CA, 95833, United States Alenfarma – Especialidades Farmaceuticas, Ordinary Quota Rua Dr Antonio Loureiro Borges No 3, Arquiparque, Miraflores, Alges, Limitada (iv) 1495-131, Portugal Allen & Hanburys Limited (iv) Ordinary 980 Great West Road, Brentford, Middlesex, TW8 9GS, England Allen & Hanburys Pharmaceutical Nigeria Limited Ordinary 24 Abimbola Way, Ilasamaja, Isolo, Lagos, Nigeria Allen Farmaceutica, S.A. Ordinary Severo Ochoa, 2, Parque Tecnologico de Madrid, Tres Cantos, Madrid, 28760, Spain Allen Pharmazeutika Gesellschaft m.b.H. Ordinary Wagenseilgasse 3, Euro Plaza, Gebäude I, 4. -

GSK Annual Report 2002

The Impact of Medicines Do more, feel better, live longer Annual Report 2002 www.gsk.com Mission Our global quest is to improve the quality of human life by enabling people to do more, feel better and live longer. Our Spirit We undertake our quest with the enthusiasm of entrepreneurs, excited by the constant search for innovation. We value performance achieved with integrity. We will attain success as a world class global leader with each and every one of our people contributing with passion and an unmatched sense of urgency. Strategic Intent We want to become the indisputable leader in our industry. GlaxoSmithKline plc is an English public limited company. Its shares are listed on the London Stock Exchange and the New York Stock Exchange. GlaxoSmithKline plc acquired Glaxo Wellcome plc and SmithKline Beecham plc on 27th December 2000 by way of a scheme of arrangement for the merger of the two companies which became effective on 27th December 2000. This report is the Annual Report of GlaxoSmithKline plc for the year ended 31st December 2002. It comprises in a single document the Annual Report of the company in accordance with United Kingdom requirements and the Annual Report on Form 20-F to the Securities and Exchange Commission in the United States of America. A summary report on the year, the Annual Review 2002, intended for the investor not needing the full detail of the Annual Report, is produced as a separate document. The Annual Review includes the joint statement by the Chairman and the Chief Executive Officer, a summary review of operations, summary financial statements and a summary remuneration report. -

United Kingdom

UNITED KINGDOM A & D Instruments Ltd Abertec Ltd Adams Business Associates Abingdon Science Park, Abingdon, Oxford OX 14 Old College King St, Aberystwyth, Dyfed SY23 Kelvin House, Totteridge Ave, High Wycombe, 3YS. 2AX. Bucks HP\3 6XG. Tel: 0235 5504201 0800 616140 Tel: 0970 622385 Telex: 35181 aby ucw Tel: 0494 465244 Fax: 0494 446788 Fax: 0235 550485 Fax: 0970 622959 Offer services in biotechnology including Supply semi-micro, analytical, general, industrial Involved in technology transfer from University of international market analysis, management and and moisture balances as well as density meters. Wales Aberystwyth. Capabilities include genetics, implementation of projects (including mergers and genetic engineering, bioproducts and acquisitions) and business development and biotransformations, biochemistry, plant and animal marketing programmes. Subsidiary offices now & A J Beveridge metabolism, biomass measurement, biosensing, established in Belguim, France and Spain. 5 Bonnington Road Lane, Leith, Edinburgh EH6 process control, tissue culture. Also undertakes 5BP. consultancy and collaborative research. Tel: 031 5535555 Fax: 031 5546068 ADC Systems Supply laboratory products. Gronant, Caernarfon, Gwynedd LL54 5BY. ABR Foods Ltd Tel: 0286 77148 Sallow Road, Weldon Industrial Estate, Corby Designs and manufactures analytical and Aaston Ltd NorthantsNNI7 \JX. preparative equipment for pathology laboratories Tel: 0536 65291 Telex: 34695 3 Abbas Business Centre, Itchen Abbas, Winchester, based on photometric determinations and robotic Fax: 0536 402228 HampshireS021IBQ. systems. Tel: 0980 6\0 391 Fax: 0980 610 898 Process wheat for the production of vital gluten as See Aaston Inc, MA, US. well as producing other related starch products, syrups and animal feed ingredients. Investigating ADM Ingredients Ltd opportunities for production of fermentation Church Manorway, Erith, Kent DA8 I DL. -

The Founding of BRESA

Volume II Appendices I – IV Appendix I THE CASE OF BRESAGEN Parcel 1: Radionucleotides Professor Robert Symons from the Biochemistry Department at the University of Adelaide developed a technique for the efficient production of 32P-labelled radionucleotides that was published in a leading scientific journal1 in 1977. These were radioactive compounds used to label DNA and RNA, and were widely used at the time in gene technology research. At the time, production of these radionucleotides was influenced by two factors: first, being radioactive and with a short half-life of 14 days, international shipping was difficult and costly. Second, manufacture was dominated by Amersham, a UK-based company, using inefficient technology, which kept prices high. This meant that increasingly, when Professor Symons had radionucleotides that were surplus to the needs of his own Department and its Centre for Gene Technology (also established in 1982), he increasingly began providing them for free to other laboratories in Australia. By the early 1980s, Bob Symons’s head of department, Professor Bill Elliott, suggested that rather than giving the radionucleotides away, he should set up a business. However, Bob Symons did not the patent the technique; as Allan Robins, a postdoctoral researcher at the time, commented, ‘this is back in the days when we were naïve academics. Nobody patented ideas, or we didn’t anyway, Bob didn’t’ (interview, 2007). 1 Nucleic Acids Research 1 According to the Bresa Product Catalogue (1984): BRESA [Ltd] was officially set up in [31] May, 1982 to develop and prepare for sale a range of high quality materials for use in gene technology. -

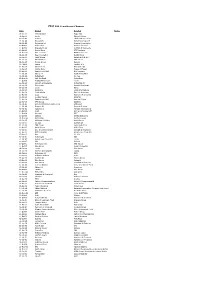

FTSE 100 Constituent History Updated

FTSE 100 Constituent Changes Date Added Deleted Notes 19-Jan-84 CJ Rothschild Eagle Star 02-Apr-84 Lonrho Magnet Sthrns. 02-Jul-84 Reuters Edinburgh Inv. Trust 02-Jul-84 Woolworths Barrat Development 19-Jul-84 Enterprise Oil Bowater Corporation 01-Oct-84 Willis Faber Wimpey (George) 01-Oct-84 Granada Group Scottish & Newcastle 01-Oct-84 Dowty Group MFI Furniture 04-Dec-84 Brit. Telecom Matthey Johnson 02-Jan-85 Dee Corporation Dowty Group 02-Jan-85 Argyll Group Berisford (S.& W.) 02-Jan-85 MFI Furniture RMC Group 02-Jan-85 Dixons Group Dalgety 01-Feb-85 Jaguar Hambro Life 01-Apr-85 Guinness (A) Enterprise Oil 01-Apr-85 Smiths Inds. House of Fraser 01-Apr-85 Ranks Hovis McD. MFI Furniture 01-Jul-85 Abbey Life Ranks Hovis McD. 01-Jul-85 Debenhams I.C. Gas 06-Aug-85 Bnk. Scotland Debenhams 01-Oct-85 Habitat Mothercare Lonrho 02-Jan-86 Scottish & Newcastle Rothschild (J) 08-Jan-86 Storehouse Habitat Mothercare 08-Jan-86 Lonrho B.H.S. 01-Apr-86 Wellcome EXCO International 01-Apr-86 Coats Viyella Sun Life Assurance 01-Apr-86 Lucas Harrisons & Crosfield 01-Apr-86 Cookson Group Ultramar 21-Apr-86 Ranks Hovis McD. Imperial Group 22-Apr-86 RMC Group Distillers 01-Jul-86 British Printing & Comms. Corp Abbey Life 01-Jul-86 Burmah Oil Bank of Scotland 01-Jul-86 Saatchi & S. Ferranti International 01-Oct-86 Bunzl Brit. & Commonwealth 01-Oct-86 Amstrad BICC 01-Oct-86 Unigate Smiths Industries 09-Dec-86 British Gas Northern Foods 02-Jan-87 Hillsdown Holdings Argyll Group 02-Jan-87 I.C. -

United States Tariff Commission Ampicillin

UNITED STATES TARIFF COMMISSION AMPICILLIN Report to the President on Preliminary Inquiry into Complaint Under Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930 TC Publication 345 Washington, D.C. November 1970 UNITED STATES TARIFF COMMISSION Glenn W. Sutton Bruce E. Clubb Will E. Leonard, Jr. George M. Moore Kenneth R. Mason, secretary Address all communications to United States Tariff Commission Washington, D. C. 20435 C ONTENTS _Lag- Introduction Alleged Unfair Methods of Competition and Unfair Acts Alleged Patent violation 2 Respondent's answer and intervention of Department of Justice Findings and ReCommendations of the Commission Statement of Commissioners Clubb and Moore in support of their affirmative recommendation 6 The. Department of Justice request 8 Requirements for a temporary exclusion order recommendation 13 Prima facie case 13 Immediate and substantial injury 15 Possible entry under bond 17 Conclusion 18 Statement of Presiding Commissioner Sutton in support of his negative recommendation 19 Statement of Commissioner Leonard in support of his negative recommendation 20 Description and Uses 23 U.S. Producers 26 Beecham, Inc Bristol-Myers Company c_ American Home Products Corporation 29 Wyeth Laboratories Ayerst Laboratories 32 Squibb, Beech-Nut, Inc *;13 U.S. Production and Sales U.S. mporter (Zenith Laboratories, Inc.) 38 U.S. imports 40 Tariff treatment Prices 42 Royalties Appendix ---Copy of the patent 46 November 21L, 1970 Introduction On January 27, 1970, Beecham Group Limited 1/ and Beecham, Inc., 2/ of Clifton, New Jersey, hereinafter referred to as complainants, filed a complaint with the United States Tariff Commission requesting relief under section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, as amended (19 U.S.C.