Making News with Citizens

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left. -

The Struggle for Hegemony in Jerusalem Secular and Ultra-Orthodox Urban Politics

THE FLOERSHEIMER INSTITUTE FOR POLICY STUDIES The Struggle for Hegemony in Jerusalem Secular and Ultra-Orthodox Urban Politics Shlomo Hasson Jerusalem, October 2002 Translator: Yoram Navon Principal Editor: Shunamith Carin Preparation for Print: Ruth Lerner Printed by: Ahva Press, Ltd. ISSN 0792-6251 Publication No. 4/12e © 2002, The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies, Ltd. 9A Diskin Street, Jerusalem 96440 Israel Tel. 972-2-5666243; Fax. 972-2-5666252 [email protected] www.fips.org.il 2 About the Author Shlomo Hasson - Professor of Geography at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and deputy director of The Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies. About the Research This book reviews the struggle for hegemony in Jerusalem between secular and ultra-orthodox (haredi) Jews. It examines the democratic deficit in urban politics formed by the rise of the haredi minority to power, and proposes ways to rectify this deficit. The study addresses the following questions: What are the characteristics of the urban democratic deficit? How did the haredi minority become a leading political force in the city? What are the implications of the democratic deficit from the perspective of the various cultural groups? What can be done in view of the fact that the non-haredi population is not only under-represented but also feels threatened and prejudiced by urban politics initiated by the city council? About the Floersheimer Institute for Policy Studies In recent years the importance of policy-oriented research has been increasingly acknowledged. Dr. Stephen H. Floersheimer initiated the establishment of a research institute that would concentrate on studies of long- range policy issues. -

November 27, 1980 30¢ Per Copy

R . I . J ewish Hi s torical ? Assoc iat i on 11 130 sessions stre e t Provide n ce , RI 0 2906 Support Jewish Read By Agencies More Than 40,000 With Your ·· ISLAND People Membership THE ONLY ENGLISH-JEWISH WEEKLY IN R. I. AND SOUTHEAST MASS VOLUME LXVIII, NUMBER 2 THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 27, 1980 30¢ PER COPY Prov. Man Elected Begin May Resign, Call Early Elections Head Of Schechter Day School After Another Narrow Confidence Vote ,\ ltchael Bohnen. son of Rabbi and Mrs J E R US AL E M ()TA) - Premic· r dectdC'd •t the la>t m1nutr t,, ,h,tatn m .. n and 1t app,•Jrs thJt his da\S are num El, Bohn,•n. has been elected President of the Mc nachem Begin wou ld be inclined to resign Eltahu. Ah,·a s chairman, .,.,d toda\ h. bc·rrd "' J m,·mht-r of lfrnit Solomon Schecht,,r Day School of Greater Boston and call earl y ei<'ctions if his government is had no e,planat,on for Assad \ b.. hav1nr, al uibor Part, edun,t lo Topple Bej(in "nee again reduced lo a slender maiorily of tC'r the three lact,on m mbt-" d=dcd un '-lean" h,k tbe uihor PJrt, oppos1t1on 1 three, as happened when ii ba rely su rvived a animou1" to vote a,z;ainsl the j?;OH'ffim(_ nl prq·,.1nnsc lo loppl, Rt·~in 11; ,R:OH·mment no-confidcncf' vole in Kn esset last week J f \ \:e11mJn I\ ou,tc--d from J ft.nil a_\ d Shimon Pn, • the part,, liad,r, said toda1 w,ult of his volc JRJ.m,t the go,emmt'nl_ one This was made clear by a ,ource close to thJt 1t I urizcnt tn hnn~ Israel "b,d, under morl' Knl'\<<·I vote h3\e to I,., c,-,untcd Begin foll owi ng the .S7-.S4 vo te on moti ons of .-,II pro~·r t"'('Onom1c m.inajtcmenl •• no-confidence in t hC' ~OVl'rn ment · s econom ic a1sa1n,t the coal1t11m "hen!"•cr the· chanCf' lk <tatcd that " "c intend to mtmduc-,, J poli cies ariS('s lo force 1h H-<-iRnat,on and tngR:er earl~ planned N.nnom,. -

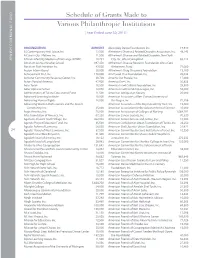

Schedule of Grants Made to Various

Schedule of Grants Made to Various Philanthropic Institutions [ Year Ended June 30, 2015 ] ORGANIZATION AMOUNT Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation, Inc. 19,930 3S Contemporary Arts Space, Inc. 12,500 Alzheimer’s Disease & Related Disorders Association, Inc. 46,245 A Cure in Our Lifetime, Inc. 11,500 Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Disorders, New York A Torah Infertility Medium of Exchange (ATIME) 20,731 City, Inc. d/b/a CaringKind 65,215 Abraham Joshua Heschel School 397,450 Alzheimer’s Disease Research Foundation d/b/a Cure JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND JEWISH COMMUNAL Abraham Path Initiative, Inc. 42,500 Alzheimer’s Fund 71,000 Accion International 30,000 Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation 15,100 Achievement First, Inc. 170,000 Am Yisroel Chai Foundation, Inc. 25,036 Achiezer Community Resource Center, Inc. 20,728 Ameinu Our People, Inc. 17,000 Actors Fund of America 47,900 America Gives, Inc. 30,856 Adas Torah 16,500 America-Israel Cultural Foundation, Inc. 25,500 Adler Aphasia Center 14,050 America-Israel Friendship League, Inc. 55,000 Administrators of Tulane Educational Fund 11,500 American Antiquarian Society 25,000 Advanced Learning Institute 10,000 American Associates of Ben-Gurion University of Advancing Human Rights 18,000 the Negev, Inc. 71,386 Advancing Women Professionals and the Jewish American Associates of the Royal Academy Trust, Inc. 15,000 Community, Inc. 25,000 American Association for the Advancement of Science 35,000 Aegis America, Inc. 75,000 American Association of Colleges of Nursing 1,064,797 Afya Foundation of America, Inc. 67,250 American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Guide to the Archival Record Groups and Collections

GUIDE TO THE ARCHIVAL RECORD GROUPS AND COLLECTIONS Jerusalem, July 2003 The contents of this Guide, and other information on the Central Zionist Archives, may be found on Internet at the following address: http://www.zionistarchives.org.il/ The e-mail address of the Archives is: [email protected] 2 Introduction This edition of the Guide to the Archival Record Groups and Collections held at the Central Zionist Archives has once again been expanded. It includes new acquisitions of material, which have been received recently at the CZA. In addition, a new section has been added, the Maps and Plans Section. Some of the collections that make up this section did appear in the previous Guide, but did not make up a separate section. The decision to collect the various collections in one section reflects the large amount of maps and plans that have been acquired in the last two years and the advancements made in this sphere at the CZA. Similarly, general information about two additional collections has been added in the Guide, the Collection of Announcements and the Collection of Badges. Explanation of the symbols, abbreviations and the structure of the Guide: Dates appearing alongside the record groups names, signify: - with regard to institutional archives: the period in which the material that is stored in the CZA was created. - with regard to personal archives: the birth and death dates of the person. Dates have not been given for living people. The numbers in the right-hand margin signify the amount of material comprising the record group, in running meters of shelf space (one running meter includes six boxes of archival material). -

Erken Seçime Giden İsrail'deki Siyasi Görünüm Ve 'Son Dakika

Kapak Konusu Birinci Netanyahu hükümeti gibi ikinci Netanyahu hükümeti de ağırlıklı olarak Sağ ve Ortodoks partilerden kurulmuştur. Erken Seçime Giden İsrail’deki Siyasi Görünüm ve ‘Son Dakika’ Sürprizleri Political Landscape and ‘Last Minute’ Surprises in Israel Heading Towards Early Elections Ali Oğuz DİRİÖZ Abstract The Israeli government’s decision to have early general elections (for the 19th Knesset) on 22 January 2013 may be seen as sudden, yet came as no real surprise. Like many preceding governments, the current Israeli government was the product of a multi-party coalition; which meant that at any serious disagreement, the possibility for its collapse was ever-present. The government experienced divergences regarding the Tal law concerning Yeshiva students’ military service, and many other differences, could not agree on the 2013 Budget, and consequently decided to head for general elections. In this election, Prime Minister Netanyahu’s Likud party and Foreign Minister Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu party decided to join forces and have a single list. This joint Likud-Yisrael Beiteinu coalition, unless a big surprise, seems most likely to become the largest group in the Knesset, and would likely lead the new government in spite of a small loss of votes. However, the recent “last moment” indictment and subsequent resignation of Foreign Affairs Minister, Avigdor Lieberman, might change the balances for the next government. Keywords: Israel, Israel 2013 Elections, Israeli Politics, Middle East, Turkey, Turkish-Israeli Relations, Middle East Peace 30 Kapak Konusu 4!" $$ 4%" "&'S)*+- 44"/)&S4/$2*& 6% Giriş 1993’den Günümüze Son 20 Yılın İsrail hükümetinin erken genel seçime gitmesi, İsrail Hükümetleri ani bir kararmış gibi gözükmekle beraber, as- lında şaşırtıcı bir durum olmamıştır. -

The Islamic State and Israel's Arab Population

The Islamic State and Israel’s Arab Population: The Scope of the Challenge and Ways to Respond Mohammed Abo Nasra The Islamic State (IS) embodies a sociopolitical phenomenon that reverberates throughout the Arab world and the world at large. This essay explores how Arab citizens of Israel view the Islamic State, and to what extent this view is influenced by political, civic, and personal factors. The study also examines the positions of Arab citizens on the global war against the Islamic State, the status of the organization in the Muslim world, the chances of its survival, and its effect on Israel’s national security. Discourse about the positions of Israel’s Arab citizens on various matters began with the founding of the state. Since the nation’s birth, the Jewish majority and the establishment have viewed the Arab sector as a population whose loyalty to the state is questionable and as such is liable to cooperate with hostile elements and be involved in actions undermining state security.1 The persistent and fundamental suspicion of Arabs has its roots in some deep-seated factors: first is the ongoing conflict between Israel and the Arab world in general, and the Palestinian people in particular. Second is the basic identification of the Arab population in Israel with the Palestinian people and its demands for a nation state. 2 Consequently, over the years an attitude to the Arab population took hold regarding security matters that shaped the relationship between the Jewish majority and the Arab minority. This attitude had a profound effect on the socioeconomic and political status of the Arab citizens and their integration into Jewish society.3 Overall, most Israeli Jews and Arabs have only distant relations, characterized by distrust and alienation, leading to a deep divide. -

Was Israel a Western Project in Palestine?

Journal of Islamicjerusalem Studies, 2020, 20(2): 189-206 DOI: 10.31456/beytulmakdis.777767 WAS ISRAEL A WESTERN PROJECT IN PALESTINE? Ibrahim KARATAŞ* ABSTRACT: This study aims to ascertain the extent to which it was Western powers or Zionists that founded Israel. The study argues that Israel was established by Western powers, while not ignoring the partial but significant role of Zionists that sought for a Jewish homeland. The West needed a Jewish homeland in order to utilise Jewish wealth, while also keeping Jews away since they were disturbed by the presence of the Jewish community. On the other hand, the World Zionist Organisation, motivated by anti-Semitism and nationalism, pioneered the idea of a Jewish national home and tried to persuade Western leaders as to the viability of a homeland in Palestine. While Zionist lobbying was influential, it can hardly be argued that they would have founded Israel without the help and permission of Western states, and in particular, the British Empire. The study aims to reveal external roles in nation-building by analysing the case of Israel. Methodologically, both quantitative and qualitative researches were used. KEYWORDS: Israel, Zionism, Mandate System, Palestine, Middle East. INTRODUCTION The State of Israel was founded in 1948 with UN Resolution 181 that partitioned the Mandate of Palestine into two states: Palestine and Israel. However, due to several wars fought between neighbouring Arab states and Israel that resulted in the defeat of the former, Israel occupied most of the Palestinian territories, thereby leaving only one single state (Israel) on the former mandate. Unlike other countries, as Israelis themselves accept, Israel does not accept multiculturalism and multi-ethnicity, recognising only Judaism as the official religion and Hebrew as the nation’s language. -

New Israel Fund Signing Anew

COMBINED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS NEW ISRAEL FUND SIGNING ANEW FOR THE YEAR ENDED DECEMBER 31, 2009 WITH SUMMARIZED FINANCIAL INFORMATION FOR 2008 NEW ISRAEL FUND SIGNING ANEW CONTENTS PAGE NO. INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT 2 EXHIBIT A - Combined Statement of Financial Position, as of December 31, 2009, with Summarized Financial Information for 2008 3 - 4 EXHIBIT B - Combined Statement of Activities and Change in Net Assets for the Year Ended December 31, 2009, with Summarized Financial Information for 2008 5 EXHIBIT C - Combined Statement of Cash Flows, for the Year Ended December 31, 2009, with Summarized Financial Information for 2008 6 NOTES TO COMBINED FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 7 - 17 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT ON SUPPLEMENTAL FINANCIAL INFORMATION 18 SCHEDULE 1 - Combining Schedule of Financial Position, for the Year Ended December 31, 2009 19 - 20 SCHEDULE 2 - Combining Schedule of Activities, for the Year Ended December 31, 2009 21 SCHEDULE 3 - Combining Schedule of Change in Net Assets, for the Year Ended December 31, 2009 22 SCHEDULE 4 - Combined Schedule of Grants, for the Year Ended December 31, 2009 23 - 30 SCHEDULE 5 - Combined Schedule of Projects, for the Year Ended December 31, 2009 31 SCHEDULE 6 - Combined Schedule of Functional Expenses, for the Year Ended December 31, 2009 32 - 33 1 GELMAN, ROSENBERG & FREEDMAN CERTIFIED PUBLIC ACCOUNTANTS INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT To the Board of Directors New Israel Fund Signing Anew Washington, D.C. We have audited the accompanying combined statement of financial position of the New Israel Fund (NIF) and Signing Anew as of December 31, 2009, and the related combined statements of activities and change in net assets and cash flows for the year then ended. -

2020 JCF Giving Report

Jewish Communal Fund GIVING 2020 REPORT ABOUT JEWISH COMMUNAL FUND Jewish Communal Fund (JCF) is the largest and most active network of Jewish funders in the nation. JCF facilitates philanthropy for more than 8,000 people associated with 4,100 funds, totaling $2 billion in charitable assets. In FY 2020, our generous Fundholders granted out $536 million—27% of our assets—to charities in all sectors. The impact of JCF’s network of funders on the Jewish community and beyond is profound. In addition to an annual unrestricted grant to UJA-Federation of New York, JCF’s Special Gifts Fund (our endowment) has granted more than $20 million since 1999 to support programs in the Jewish community at home and abroad, including kosher food pantries and soup kitchens, day camp scholarships for children from low-income homes, and programs for Holocaust survivors with dementia. These charities are selected with the assistance of UJA-Federation of NY. For a simpler, easier, smarter way to give, look no further than the Jewish Communal Fund. To learn more about JCF, visit jcfny.org or call us at (212) 752-8277. INTRODUCTION TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Letter from the President and CEO 2 Introduction 3–6 The JCF Philanthropic Community 7–15 Grants 16 Contributions 17–28 Grants Listing 2 www.jcfny.org • 212-752-8277 Letter from the President and CEO JCF’s extraordinarily generous Fundholders increased their giving to meet the tremendous needs that arose amidst the COVID-19 pandemic. In FY 2020, JCF Fundholders recommended more than 64,000 grants totaling a record-breaking $536 million to charities in every sector. -

The Legal Philosophies of Religious Zionism 1937-1967 Alexander Kaye Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Th

The Legal Philosophies of Religious Zionism 1937-1967 Alexander Kaye Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2012 Alexander Kaye All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Legal Philosophies of Religious Zionism 1937-1967 Alexander Kaye This dissertation is an attempt to recover abandoned pathways in religious Zionist thought. It identifies a fundamental shift in the legal philosophy of religious Zionists, demonstrating that around the time of the establishment of the State of Israel, religious Zionists developed a new way of thinking about the relationship between law and the state. Before this shift took place, religious Zionist thinkers affiliated with a variety of legal and constitutional philosophies. As shown in chapter 1, the leaders of the religious kibbutz movement advocated a revolutionary, almost anarchic, approach to law. They (in theory, at least,) only accepted rules that emerged spontaneously from the spirit of their religious and national life, even if that meant departing from traditional halakha. Others had a more positive attitude towards law but, as chapter 2 shows, differed widely regarding the role of halakha in the constitution of the Jewish state. They covered a spectrum from, at one extreme, the call for a complete separation between religion and state to, on the other, the call a rabbinic oversight of all legislation. They all, however, were legal pluralists; they agreed that a single polity may have within it a plurality of legitimate sources of legal authority and that, even in a Jewish state, other kinds of legislation may hold authority alongside halakha. -

Israel: Growing Pains at 60

Viewpoints Special Edition Israel: Growing Pains at 60 The Middle East Institute Washington, DC Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints are another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US rela- tions with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org The maps on pages 96-103 are copyright The Foundation for Middle East Peace. Our thanks to the Foundation for graciously allowing the inclusion of the maps in this publication. Cover photo in the top row, middle is © Tom Spender/IRIN, as is the photo in the bottom row, extreme left.