Hans Haacke's Zero Hour

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Discovering the Contemporary

of formalist distance upon which modernists had relied for understanding the world. Critics increasingly pointed to a correspondence between the formal properties of 1960s art and the nature of the radically changing world that sur- rounded them. In fact formalism, the commitment to prior- itizing formal qualities of a work of art over its content, was being transformed in these years into a means of discovering content. Leo Steinberg described Rauschenberg’s work as “flat- bed painting,” one of the lasting critical metaphors invented 1 in response to the art of the immediate post-World War II Discovering the Contemporary period.5 The collisions across the surface of Rosenquist’s painting and the collection of materials on Rauschenberg’s surfaces were being viewed as models for a new form of realism, one that captured the relationships between people and things in the world outside the studio. The lesson that formal analysis could lead back into, rather than away from, content, often with very specific social significance, would be central to the creation and reception of late-twentieth- century art. 1.2 Roy Lichtenstein, Golf Ball, 1962. Oil on canvas, 32 32" (81.3 1.1 James Rosenquist, F-111, 1964–65. Oil on canvas with aluminum, 10 86' (3.04 26.21 m). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. 81.3 cm). Courtesy The Estate of Roy Lichtenstein. New Movements and New Metaphors Purchase Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman and Lillie P. Bliss Bequest (both by exchange). Acc. n.: 473.1996.a-w. Artists all over the world shared U.S. -

The Inflation of Abstraction | the New Yorker

6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker The Art World The Inflation of Abstraction The Met’s show of Abstract Expressionism wants to remake the canon. By Peter Schjeldahl December 31, 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 1/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker Mark Rothko’s “No. 3,” from 1953, his peak year of miracles. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Courtesy ARS he rst room of “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera,” a wishfully canon- T expanding show of painting and sculpture from the past eight decades, at the Metropolitan Museum, affects like a mighty organ chord. It contains the museum’s two best paintings by Jackson Pollock: “Pasiphaë” (1943), a quaking compaction of https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 2/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker mythological elements named for the accursed mother of the Minotaur, and “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” (1950), a singing orchestration of drips in black, white, brown, and teal enamel—bluntly material and, inextricably, sublime. There are six Pollock drawings, too, and “Number 7” (1952), one of his late, return-to- guration paintings in mostly black on white, of an indistinct but hieratic head. The adjective “epic” does little enough to honor Pollock’s mid-century glory, which anchors the standard art-historical saga of Abstract Expressionism—“The Triumph of American Painting,” per the title of a 1976 book on the subject by Irving Sandler —as a revolution that stole the former thunder of Paris and set a stratospheric benchmark for subsequent artists. -

The Authenticity of Ambiguity: Dada and Existentialism

THE AUTHENTICITY OF AMBIGUITY: DADA AND EXISTENTIALISM by ELIZABETH FRANCES BENJAMIN A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Department of Modern Languages College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham August 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ii - ABSTRACT - Dada is often dismissed as an anti-art movement that engaged with a limited and merely destructive theoretical impetus. French Existentialism is often condemned for its perceived quietist implications. However, closer analysis reveals a preoccupation with philosophy in the former and with art in the latter. Neither was nonsensical or meaningless, but both reveal a rich individualist ethics aimed at the amelioration of the individual and society. It is through their combined analysis that we can view and productively utilise their alignment. Offering new critical aesthetic and philosophical approaches to Dada as a quintessential part of the European Avant-Garde, this thesis performs a reassessment of the movement as a form of (proto-)Existentialist philosophy. The thesis represents the first major comparative study of Dada and Existentialism, contributing a new perspective on Dada as a movement, a historical legacy, and a philosophical field of study. -

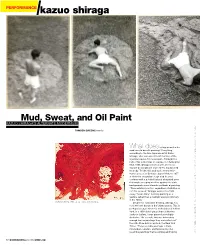

Performance Kazuo Shiraga

PERFORMANCE kazuo shiraga Mud, Sweat, and Oil Paint KAZUO SHIRAGA’S ALTERNATE MODERNIsm. TAMSEN GREENEwords What does rolling around in the mud have to do with painting? Everything, according to the late Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, who was a prominent member of the legendary Gutai Art Association. Although the bulk of his output was on canvas, in Challenging Mud, 1955, Shiraga wrestled with a formless mixture of wall plaster and cement that bruised his body. To him, this and such other perfor- mance pieces as Sanbaso-Super Modern, 1957— in which he swayed on stage clad in a red costume with a pointed hat and elongated arms that made sweeping motions against the dark background—were alternate methods of painting. “There exists my action, regardless of whether or not it is secured,” Shiraga wrote in his 1955 essay “Action Only.” Defining painting as a gesture rather than a medium was revolutionary in the 1950s. Chizensei Kirenji, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS, 51¼ X 63¾ IN. Despite his innovative thinking, Shiraga has not been well known in the United States. This is perhaps because when his work debuted in New York, in a 1958 Gutai group show at Martha Jackson Gallery, it was panned as multiply derivative. “As records, they are interesting enough, but as paintings they are ineffectual,” the critic Dore Ashton wrote in the New York Times. “They resemble paintings in Paris, Amsterdam, London, and Mexico City that resemble paintings that resemble paintings by FROM TOP: THREE IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER; VERVOORDT FOUNDATION COLLECTION. OPPOSITE: BOTH IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER 32 MODERN PAINTERS APRIL 2010 ARTINFO.COM Performance stills from Challenging Mud, third execution. -

San Francisco Art Institute Presents Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT: Janette Andrawes 415.749.4515 [email protected] San Francisco Art Institute Presents Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response First West Coast Survey Exhibition of Avant-Garde, Postwar Japanese Art Movement Features Site-Specific Contemporary Responses to Classic Gutai Performative Works Exhibition: Experimental Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Mid-Winter Burning Sun: Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response Curators: John Held, Jr. and Andrew McClintock Venue: Walter and McBean Galleries San Francisco Art Institute 800 Chestnut Street, San Francisco, CA Dates: February 8–March 30, 2013 Media Preview: Friday, February 8, 5:00–6:00 pm Cost: Free and Open to the Public San Francisco, CA (January 9, 2013) — The San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) is proud to announce the first West Coast survey exhibition of Gutai (1954-1972)—a significant avant-garde artist collective in postwar Japan whose overriding directive was: "Do something no one's ever done before." Rejecting the figurative and abstract art of the era, and in an effort to transform the Japanese psyche from wartime regimentation to independence of thought, Gutai artists fulfilled their commitment to innovative practices by producing art through concrete, performative actions. With a diverse assembly of historical and contemporary art, including several site- specific performances commissioned exclusively for SFAI, Experimental Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Mid-Winter Burning Sun: Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response creates a dialogue with classic Gutai works while demonstrating the lasting significance and radical energy of this movement. This exhibition showcases North American, neo-conceptualist artists' responses to groundbreaking Gutai performances; dozens of original paintings, video, photographs, and ephemera from private collections; and an expansive collection of Mail Art from more than 30 countries. -

N. 17 Dicembre 2017/Marzo 2018 a Painting by Hans Haacke

n. 17 dicembre 2017/marzo 2018 A Painting by Hans Haacke : Dematerializing Labor di Andreas Petrossiants Artistic activity is a mode – a singular form – of labor power . Antonio Negri, 2008 1 To center an essay concerning the more - than - expansive discursive field denoted by «painting», on just one work by Hans Haacke, might at first glance seem misplaced. However, while Haacke’s work was surely instrumental for the shifts in Western artistic pra ctice comprising the «conceptual turn» of the 1960s and the parallel «dematerialization» of the art object, his painting Taking Stock (unfinished) (1983 - 1984 ) not only brings such broad period generalizations into question, but also examines the labor invo lved in producing (the value of) a painting [fig. 1]. Taking Stock (unfinished) , first exhibited at the Tate Gallery in 1984, depicts Margaret Thatcher in the style of Victorian portraiture, encoded with information concerning the careers and art collectio ns of Charles and Doris Saatchi, as well as their ties to Thatcher and her reactionary government. Referring specifically to the medium and style of the work, Haacke remarks that it was produced to cite and critique how Thatcher «expressly promotes Victori an values, nineteenth century conservative policies at the end of the twentieth century». He continues: « Thatcher would like to rule an imperial Britain. The Falklands War was typical of this mentality». 2 This essay proposes to displace and problematize the traditional discourses applied to historicizing conceptual art, and to describe how Haacke employs both physical «painterly» and immaterial conceptual labor to produce a material object. He fosters a str ategy mirroring the changes in the structure and critical position of the (art) worker 1 during the late 1960s. -

Labyrinthine Variations 12.09.11 → 05.03.12

WANDER LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS PRESS PACK 12.09.11 > 05.03.12 centrepompidou-metz.fr PRESS PACK - WANDER, LABYRINTHINE VARIATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION .................................................... 02 2. THE EXHIBITION E I TH LAByRINTH AS ARCHITECTURE ....................................................................... 03 II SpACE / TImE .......................................................................................................... 03 III THE mENTAL LAByRINTH ........................................................................................ 04 IV mETROpOLIS .......................................................................................................... 05 V KINETIC DISLOCATION ............................................................................................ 06 VI CApTIVE .................................................................................................................. 07 VII INITIATION / ENLIgHTENmENT ................................................................................ 08 VIII ART AS LAByRINTH ................................................................................................ 09 3. LIST OF EXHIBITED ARTISTS ..................................................................... 10 4. LINEAgES, LAByRINTHINE DETOURS - WORKS, HISTORICAL AND ARCHAEOLOgICAL ARTEFACTS .................... 12 5.Om C m ISSIONED WORKS ............................................................................. 13 6. EXHIBITION DESIgN ....................................................................................... -

Conceptual Art: a Critical Anthology

Conceptual Art: A Critical Anthology Alexander Alberro Blake Stimson, Editors The MIT Press conceptual art conceptual art: a critical anthology edited by alexander alberro and blake stimson the MIT press • cambridge, massachusetts • london, england ᭧1999 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval)without permission in writing from the publisher. This book was set in Adobe Garamond and Trade Gothic by Graphic Composition, Inc. and was printed and bound in the United States of America. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Conceptual art : a critical anthology / edited by Alexander Alberro and Blake Stimson. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-262-01173-5 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Conceptual art. I. Alberro, Alexander. II. Stimson, Blake. N6494.C63C597 1999 700—dc21 98-52388 CIP contents ILLUSTRATIONS xii PREFACE xiv Alexander Alberro, Reconsidering Conceptual Art, 1966–1977 xvi Blake Stimson, The Promise of Conceptual Art xxxviii I 1966–1967 Eduardo Costa, Rau´ l Escari, Roberto Jacoby, A Media Art (Manifesto) 2 Christine Kozlov, Compositions for Audio Structures 6 He´lio Oiticica, Position and Program 8 Sol LeWitt, Paragraphs on Conceptual Art 12 Sigmund Bode, Excerpt from Placement as Language (1928) 18 Mel Bochner, The Serial Attitude 22 Daniel Buren, Olivier Mosset, Michel Parmentier, Niele Toroni, Statement 28 Michel Claura, Buren, Mosset, Toroni or Anybody 30 Michael Baldwin, Remarks on Air-Conditioning: An Extravaganza of Blandness 32 Adrian Piper, A Defense of the “Conceptual” Process in Art 36 He´lio Oiticica, General Scheme of the New Objectivity 40 II 1968 Lucy R. -

Press Release Zurich, 3 February 2017 Hans Haacke Receives The

Press release Zurich, 3 February 2017 Hans Haacke receives the Roswitha Haftmann Prize Hans Haacke (b. 1936) receives Europe’s best endowed art award, worth CHF 150,000, from the Roswitha Haftmann Foundation. The Board of the Roswitha Haftmann Foundation has decided to award the Roswitha Haftmann Prize to Hans Haacke in recognition of his life’s work. The jury praised his courageous and unflinching commitment over many decades and his ability to foster debate on social issues through provocative art, but also his intellectual brilliance and the formal quality of his works. Hans Haacke was born in Cologne in 1936 and has lived in New York since 1965. He has aroused particular controversy for the political aspects of his work. CONCEPTUAL ART AND LAND ART Haacke studied at the Staatliche Werkakademie, Kassel, from 1956 to 1960. His early works already revolved around systems and processes and analysed their workings – and failures. The young artist presented interactions between physical and biological systems, animals, plants and states of water and wind; he also made forays into land art. From 1970 onwards, he increasingly turned his attention to political developments and the mechanisms of manipula- tion – of opinions, sensibilities and historical facts. MARKET, POLITICS, MORALITY The abrupt cancellation of his exhibition at New York’s Guggenheim Museum in 1971, which was to include his ‘Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971’, on property ownership and speculation, led to a heated debate on the politics of conceptual art. In Cologne in 1974 he put forward a provocative project on the provenance of a still life by Edouard Manet purchased for the Wallraf Richartz Museum on the initiative of the then chairman of its patron association Hermann Josef Abs, and turned the spotlight on his role in the Third Reich. -

Hans Haacke Biography

P A U L A C O O P E R G A L L E R Y Hans Haacke Biography 1936 Born Cologne, Germany 1956-60 Staatliche Werkakademie (State Art Academy), Kassel, Staatsexamen (equivalent of M.F.A.) 1960-61 Stanley William Hayter's Atelier 17, Paris 1961 Tyler School of Fine Arts, Temple University, Philadelphia 1962 Moves to New York 1963-65 Return to Cologne. Teaches at Pädagogische Hochschule, Kettwig, and other institutions 1966-67 Teaches at University of Washington, Seattle; Douglas College, Rutgers University, New Jersey; Philadelphia College of Art 1967 - 2002 Teaches at Cooper Union, New York (Professor of Art Emeritus) 1973 Guest Professorship, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1979 Guest Professorship, Gesamthochschule, Essen 1994 Guest Professorship, Hochschule für Bildende Künste, Hamburg 1997 Regents Lecturer, University of California, Berkeley Lives in New York (since 1965) Awards 1960 Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) 1961 Fulbright Fellowship 1973 John Simon Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship 1978 National Endowment for the Arts 1991 College Art Association Distinguished Artist Award for Lifetime Achievement Deutscher Kritikerpreis for 1990 Honorary Doctorate in Fine Arts, Oberlin College 1993 Golden Lion (shared with Nam June Paik), Venice Biennale 1997 Kurt-Eisner-Foundation, Munich Honorary Doctorate Bauhaus-Universität Weimar 2001 Prize of Helmut-Kraft-Stiftung, Stuttgart 2002 College Art Association Distinguished Teaching of Art Award 2004 Peter-Weiss-Preis, Bochum 2008 Honorary Doctorate, San Francisco Art Institute -

Hans Haacke, Or the Museum As Degenerate Utopia, Kritikos V.4, Marc

Hans Haacke, or the Museum as Degenerate Utopia, Kritikos V.4, Marc... http://intertheory.org/english.htm an international and interdisciplinary journal of postmodern cultural sound, text and image Volume 4, March 2007, ISSN 1552-5112 Hans Haacke, or the Museum as Degenerate Utopia Travis English To control a museum means precisely to control the representations of a community and its highest values and truths. Carol Duncan, “The Art Museum as Ritual” [1] Since the early 1970s, much of Hans Haacke’s work has focused on demystifying the relationship between museums and corporations. Museums present themselves to the public as the autonomous realm of the aesthetic, as the purveyors and protectors of cultural artifacts, while corporations present themselves as enlightened benefactors—patrons--truly interested in the cultural well-being of the community-at-large. In this sense, these two realms—cultural and corporate—do not hide their relations. In fact, most museums display the names of their corporate sponsors proudly on bronze plaques that imply the permanence of a grave marker, as if a symbiotic relationship has always existed between the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Bank of America, along with a host of other global corporations. Haacke’s work relies upon the strategies through which museums and corporations naturalize their interdependent relationships with each other. For Haacke, this relationship between museums and their corporate sponsors is one of exchange and not simply one of patronage. He writes, “…it is important to distinguish between the traditional notion of patronage and the public 1 von 20 11.06.2012 12:15 Hans Haacke, or the Museum as Degenerate Utopia, Kritikos V.4, Marc.. -

ZERO ERA Mack and His Artist Friends

PRESS RELEASE: for immediate publication ZERO ERA Mack and his artist friends 5th September until 31st October 2014 left: Heinz Mack, Dynamische Struktur schwarz-weiß, resin on canvas, 1961, 130 x 110 cm right: Otto Piene, Es brennt, Öl, oil, fire and smoke on linen, 1966, 79,6 x 99,8 cm Beck & Eggeling presents at the start of the autumn season the exhibition „ZERO ERA. Mack and his artist friends“ - works from the Zero movement from 1957 until 1966. The opening will take place on Friday, 5th September 2014 at 6 pm at Bilker Strasse 5 and 4-6 in Duesseldorf, on the occasion of the gallery weekend 'DC Open 2014'. Heinz Mack will be present. After ten years of intense and successful cooperation between the gallery and Heinz Mack, culminating in the monumental installation project „The Sky Over Nine Columns“ in Venice, the artist now opens up his private archives exclusively for Beck & Eggeling. This presents the opportunity to delve into the ZERO period, with a focus on the oeuvre of Heinz Mack and his relationship with his artist friends of this movement. Important artworks as well as documents, photographs, designs for invitations and letters bear testimony to the radical and vanguard ideas of this period. To the circle of Heinz Mack's artist friends belong founding members Otto Piene and Günther Uecker, as well as the artists Bernard Aubertin, Hermann Bartels, Enrico Castellani, Piero BECK & EGGELING BILKER STRASSE 5 | D 40213 DÜSSELDORF | T +49 211 49 15 890 | [email protected] Dorazio, Lucio Fontana, Hermann Goepfert, Gotthard Graubner, Oskar Holweck, Yves Klein, Yayoi Kusama, Walter Leblanc, Piero Manzoni, Almir da Silva Mavignier, Christian Megert, George Rickey, Jan Schoonhoven, Jesús Rafael Soto, Jean Tinguely and Jef Verheyen, who will also be represented in this exhibition.