The First Gutai Exhibition I N Japan Marks the Dissemination Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inflation of Abstraction | the New Yorker

6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker The Art World The Inflation of Abstraction The Met’s show of Abstract Expressionism wants to remake the canon. By Peter Schjeldahl December 31, 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 1/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker Mark Rothko’s “No. 3,” from 1953, his peak year of miracles. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Courtesy ARS he rst room of “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera,” a wishfully canon- T expanding show of painting and sculpture from the past eight decades, at the Metropolitan Museum, affects like a mighty organ chord. It contains the museum’s two best paintings by Jackson Pollock: “Pasiphaë” (1943), a quaking compaction of https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 2/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker mythological elements named for the accursed mother of the Minotaur, and “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” (1950), a singing orchestration of drips in black, white, brown, and teal enamel—bluntly material and, inextricably, sublime. There are six Pollock drawings, too, and “Number 7” (1952), one of his late, return-to- guration paintings in mostly black on white, of an indistinct but hieratic head. The adjective “epic” does little enough to honor Pollock’s mid-century glory, which anchors the standard art-historical saga of Abstract Expressionism—“The Triumph of American Painting,” per the title of a 1976 book on the subject by Irving Sandler —as a revolution that stole the former thunder of Paris and set a stratospheric benchmark for subsequent artists. -

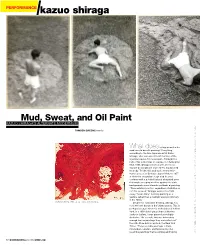

Performance Kazuo Shiraga

PERFORMANCE kazuo shiraga Mud, Sweat, and Oil Paint KAZUO SHIRAGA’S ALTERNATE MODERNIsm. TAMSEN GREENEwords What does rolling around in the mud have to do with painting? Everything, according to the late Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, who was a prominent member of the legendary Gutai Art Association. Although the bulk of his output was on canvas, in Challenging Mud, 1955, Shiraga wrestled with a formless mixture of wall plaster and cement that bruised his body. To him, this and such other perfor- mance pieces as Sanbaso-Super Modern, 1957— in which he swayed on stage clad in a red costume with a pointed hat and elongated arms that made sweeping motions against the dark background—were alternate methods of painting. “There exists my action, regardless of whether or not it is secured,” Shiraga wrote in his 1955 essay “Action Only.” Defining painting as a gesture rather than a medium was revolutionary in the 1950s. Chizensei Kirenji, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS, 51¼ X 63¾ IN. Despite his innovative thinking, Shiraga has not been well known in the United States. This is perhaps because when his work debuted in New York, in a 1958 Gutai group show at Martha Jackson Gallery, it was panned as multiply derivative. “As records, they are interesting enough, but as paintings they are ineffectual,” the critic Dore Ashton wrote in the New York Times. “They resemble paintings in Paris, Amsterdam, London, and Mexico City that resemble paintings that resemble paintings by FROM TOP: THREE IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER; VERVOORDT FOUNDATION COLLECTION. OPPOSITE: BOTH IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER 32 MODERN PAINTERS APRIL 2010 ARTINFO.COM Performance stills from Challenging Mud, third execution. -

San Francisco Art Institute Presents Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT: Janette Andrawes 415.749.4515 [email protected] San Francisco Art Institute Presents Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response First West Coast Survey Exhibition of Avant-Garde, Postwar Japanese Art Movement Features Site-Specific Contemporary Responses to Classic Gutai Performative Works Exhibition: Experimental Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Mid-Winter Burning Sun: Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response Curators: John Held, Jr. and Andrew McClintock Venue: Walter and McBean Galleries San Francisco Art Institute 800 Chestnut Street, San Francisco, CA Dates: February 8–March 30, 2013 Media Preview: Friday, February 8, 5:00–6:00 pm Cost: Free and Open to the Public San Francisco, CA (January 9, 2013) — The San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) is proud to announce the first West Coast survey exhibition of Gutai (1954-1972)—a significant avant-garde artist collective in postwar Japan whose overriding directive was: "Do something no one's ever done before." Rejecting the figurative and abstract art of the era, and in an effort to transform the Japanese psyche from wartime regimentation to independence of thought, Gutai artists fulfilled their commitment to innovative practices by producing art through concrete, performative actions. With a diverse assembly of historical and contemporary art, including several site- specific performances commissioned exclusively for SFAI, Experimental Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Mid-Winter Burning Sun: Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response creates a dialogue with classic Gutai works while demonstrating the lasting significance and radical energy of this movement. This exhibition showcases North American, neo-conceptualist artists' responses to groundbreaking Gutai performances; dozens of original paintings, video, photographs, and ephemera from private collections; and an expansive collection of Mail Art from more than 30 countries. -

Oral History Interview with Hans Namuth, 1971 Aug. 12-Sept. 14

Oral history interview with Hans Namuth, 1971 Aug. 12-Sept. 14 Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Hans Namuth on August 12 and September 8, 1971. The interview took place in New York City, and was conducted by Paul Cummings for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Interview PAUL CUMMINGS: It's August 12, 1971 - Paul Cummings talking to Hans Namuth in his studio in New York City. You were born in Germany - right? HANS NAMUTH: Right. PAUL CUMMINGS: Could you tell me something about life there and growing up and education and how you got started? You were born in - what? - 1915? HANS NAMUTH: Yes. I grew up during the war years and inflation. I have memories of the French Occupation and shooting in the streets. The French occupied Essen. We had a French deserter living with us who taught me my first French. I went to the equivalent of a gymnasium, Humboldt Oberrealschule in Essen, hating school, loathing school. I would say it was a prison. Eventually I started to work in a bookshop in Essen at the age of seventeen and became very affiliated with Leftist groups in 1932 when everything was brewing and for a moment we didn't know whether they were going to go all the way Left or all the way Right. I think the Communist and the Socialist Parties at the time lost a big chance of gaining power in Germany by not uniting in 1931-1932. -

Allan Sekula

Allan Sekula Polonia and Other Fables The Renaissance Society September 20 – December 13, 2009 at The University of Chicago 5 T a C P 8 t h h h 1 o i e T c 1 n h a R S e g The e : o e o ( u U n 7 , t a 7 n I h l l 3 i i i s E n v ) s 7 o l Renaissance e l i 0 a i r s s 2 s n A 6 - i c t 8 v 0 e y 6 e 6 7 n 3 S Society o 0 u 7 f o e c C i h Mòwimy po Polsku at The University of Chicago e i t c 5811 South Ellis Avenue y a 4th floor g o In 1950, Hans Namuth documented Jackson variety of photographic tropes ranging from means of thinking through rather than excluding Nothing could be further from the pit’s Chicago, IL 60637 Pollock in what are now iconic photographs. clandestine snapshots to formal portraiture, from the self, beginning with the most basic social testosterone-fueled mania than Sekula’s portrait unit, the family. Autobiography recurs in varying of an extremely slight female trader. She stands, Museum Hours One features a pensive Pollock crouched serial to aerial photography, and from street Tuesday - Friday: 10am - 5pm amongst abraded weeds in front of a weathered photography to ethnography in the vein of degrees of subtlety throughout his work. It is arms at her side, in front of a confetti-strewn Saturday, Sunday: 12- 5pm Model T Ford. -

Downloaded Or Projected for Classroom Use

FEBUARY 15, 2013–MAY 8, 2013 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Teacher Resource Unit A NOTE TO TEACHERS Gutai: Splendid Playground is the first U.S. museum retrospective exhibition ever devoted to Gutai, the most influential artists’ collective and artistic movement in postwar Japan and among the most important international avant-garde movements of the 1950s and 1960s. The exhibition aims to demonstrate Gutai’s extraordinary range of bold and innovative creativity; to examine its aesthetic strategies in the cultural, social, and political context of postwar Japan and the West; and to further establish Gutai in an expanded history of modern art. Organized thematically and chronologically to explore Gutai’s unique approach to materials, process, and performativity, this exhibition explores the group’s radical experimentation across a range of mediums and styles, and demonstrates how individual artists pushed the limits of what art could be and mean in a post-atomic age. The range includes painting (gestural abstraction and post-constructivist abstraction), conceptual art, experimental performance and film, indoor and outdoor installation art, sound art, mail art, interactive or “playful” art, light art, and kinetic art. The Guggenheim show comprises some 120 objects by twenty-five artists on loan from major museum and private collections in Japan, the United States, and Europe, and features both iconic and lesser-known Gutai works to present a rich survey reflecting new scholarship, especially on so-called “second phase” works dating from 1962–72. Gutai: Splendid Playground is organized by Ming Tiampo, Associate Professor of Art History, Carleton University, and Alexandra Munroe, Samsung Senior Curator of Asian Art, Guggenheim Museum. -

A Finding Aid to the Hans Namuth Photographs and Papers, 1945-1985, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Hans Namuth Photographs and Papers, 1945-1985, in the Archives of American Art Kelly Overstreet 2017 July 24 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 2 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 3 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Alfred Stieglitz Film Project, 1945-circa 1981........................................... 5 Series 2: Professional Files, 1953-1985.................................................................. 9 Series 3: Photographs, 1945-1984........................................................................ 10 Hans Namuth photographs and papers AAA.namuhans -

Kusama 2 1 Zero Gutai Kusama

ZERO GUTAI KUSAMA 2 1 ZERO GUTAI KUSAMA VIEWING Bonhams 101 New Bond Street London, W1S 1SR Sunday 11 October 11.00 - 17.00 Monday 12 October 9.00 - 18.00 Tuesday 13 October 9.00 - 18.00 Wednesday 14 October 9.00 - 18.00 Thursday 15 October 9.00 - 18.00 Friday 16 October 9.00 - 18.00 Monday 19 October 9.00 - 17.00 Tuesday 20 October 9.00 - 17.00 EXHIBITION CATALOGUE £25.00 ENQUIRIES Ralph Taylor +44 (0) 20 7447 7403 [email protected] Giacomo Balsamo +44 (0) 20 7468 5837 [email protected] PRESS ENQUIRIES +44 (0) 20 7468 5871 [email protected] 2 1 INTRODUCTION The history of art in the 20th Century is punctuated by moments of pure inspiration, moments where the traditions of artistic practice shifted on their foundations for ever. The 1960s were rife with such moments and as such it is with pleasure that we are able to showcase the collision of three such bodies of energy in one setting for the first time since their inception anywhere in the world with ‘ZERO Gutai Kusama’. The ZERO and Gutai Groups have undergone a radical reappraisal over the past six years largely as a result of recent exhibitions at the New York Guggenheim Museum, Berlin Martin Gropius Bau and Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum amongst others. This escalation of interest is entirely understandable coming at a time where experts and collectors alike look to the influences behind the rapacious creativity we are seeing in the Contemporary Art World right now and in light of a consistently strong appetite for seminal works. -

Reconsidering New Objectivity: Albert Renger-Patzsch and Die

RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL (Under the Direction of NELL ANDREW) ABSTRACT In December of 1928, the Munich-based publisher, Kurt Wolff released a book with a new concept: a collection of one-hundred black and white photographs by Albert Renger-Patzsch. Titled Die Welt ist schön, the book presented a remarkable diversity of subjects visually unified by Renger-Patzsch’s straight-forward aesthetic. While widely praised at the time of its release, the book exists in relative obscurity today. Its legacy was cemented by the negative criticism it received in two of Walter Benjamin’s essays, “Little History of Photography” (1931) and “The Author as Producer” (1934). This paper reexamines the book in within the context of its reception, reconsidering the book’s legacy and its ties to the New Objectivity movement in Weimar. INDEX WORDS: Albert Renger-Patzsch, Die Welt ist schön, Photography, New Objectivity, Sachlichkeit, New Vision, Painting Photography Film, Walter Benjamin, Lázsló Moholy-Nagy RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET HANKEL BA, Columbia College Chicago, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2017 © 2017 Margaret E. Hankel All Rights Reserved RECONSIDERING NEW OBJECTIVITY: ALBERT RENGER-PATZSCH AND DIE WELT IST SCHÖN by MARGARET E. HANKEL Major Professor: Nell Andrew Committee: Alisa Luxenberg Janice Simon Electronic Version Approved: Suzanne Barbour Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2017 iv DEDICATION For my mother and father v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Many thanks to those who have read this work in its various stages of completion: to my advisor, Nell Andrew, whose kind and sage guidance made this project possible, to my committee members Janice Simon and Alisa Luxenberg, to Isabelle Wallace, and to my colleague, Erin McClenathan. -

After World War II, a Devastated Japan Processed the Impact of the Atomic Bomb and Faced a Cultural Void

New York, NY… After World War II, a devastated Japan processed the impact of the atomic bomb and faced a cultural void. It was in this atmosphere of existential alienation that the Gutai Art Association (Gutai Bijutsu Kyokai) – a group of about twenty young artists, rallying around the charismatic painter Jiro Yoshihara – emerged in the mid-1950s to challenge convention. Although keenly aware of Japan’s artistic traditions, the Gutai artists attempted to distance themselves from the sense of defeat and impotence that pervaded their country, and to overcome the past completely with ‘art that has never existed before’. They burst out of the expected confines of painting with daring works that demonstrated a freewheeling relationship between art, body, space and time. Dismissed by Japanese critics as spectacle makers, the Gutai artists nevertheless produced a profound legacy of aesthetic experimentation, influencing Western critics and anticipating Abstract Expressionism, Arte Povera, Fluxus, and Conceptual Art. ‘A Visual Essay on Gutai’ traces efforts by these artists to resolve the inherent contradictions between traditions of painting – the making of images on a flat, framed plane – and the core tenets of a movement that called for experimentation, individuality, unexpected materials, and, perhaps above all, physical action and psychological freedom. On view at Hauser & Wirth New York will be more than 30 works spanning twenty years, all of them exciting responses to the constraints of painting and the limits of time itself. Curated by Midori Nishizawa and organized with Olivier Renaud-Clément, ‘A Visual Essay on Gutai’ also marks the half-century anniversary of Gutai’s first U.S. -

A Companion to Digital Art WILEY BLACKWELL COMPANIONS to ART HISTORY

A Companion to Digital Art WILEY BLACKWELL COMPANIONS TO ART HISTORY These invigorating reference volumes chart the influence of key ideas, discourses, and theories on art, and the way that it is taught, thought of, and talked about throughout the English‐speaking world. Each volume brings together a team of respected international scholars to debate the state of research within traditional subfields of art history as well as in more innovative, thematic configurations. Representing the best of the scholarship governing the field and pointing toward future trends and across disciplines, the Blackwell Companions to Art History series provides a magisterial, state‐ of‐the‐art synthesis of art history. 1 A Companion to Contemporary Art since 1945 edited by Amelia Jones 2 A Companion to Medieval Art edited by Conrad Rudolph 3 A Companion to Asian Art and Architecture edited by Rebecca M. Brown and Deborah S. Hutton 4 A Companion to Renaissance and Baroque Art edited by Babette Bohn and James M. Saslow 5 A Companion to British Art: 1600 to the Present edited by Dana Arnold and David Peters Corbett 6 A Companion to Modern African Art edited by Gitti Salami and Monica Blackmun Visonà 7 A Companion to Chinese Art edited by Martin J. Powers and Katherine R. Tsiang 8 A Companion to American Art edited by John Davis, Jennifer A. Greenhill and Jason D. LaFountain 9 A Companion to Digital Art edited by Christiane Paul 10 A Companion to Public Art edited by Cher Krause Knight and Harriet F. Senie A Companion to Digital Art Edited by Christiane Paul -

“Just What Was It That Made U.S. Art So Different, So Appealing?”

“JUST WHAT WAS IT THAT MADE U.S. ART SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING?”: CASE STUDIES OF THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE PAINTING IN LONDON, 1950-1964 by FRANK G. SPICER III Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Ellen G. Landau Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2009 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Frank G. Spicer III ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Dr. Ellen G. Landau (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________Dr. Anne Helmreich Dr. Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Dr. Kurt Koenigsberger ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ December 18, 2008 (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Table of Contents List of Figures 2 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 12 Introduction 14 Chapter I. Historiography of Secondary Literature 23 II. The London Milieu 49 III. The Early Period: 1946/1950-55 73 IV. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 1, The Tate 94 V. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 2 127 VI. The Later Period: 1960-1962 171 VII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 1 213 VIII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 2 250 Concluding Remarks 286 Figures 299 Bibliography 384 1 List of Figures Fig. 1 Richard Hamilton Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956) Fig. 2 Modern Art in the United States Catalogue Cover Fig. 3 The New American Painting Catalogue Cover Fig.