Adolph Gottlieb's Rolling and Yoshihara Jiro's Red Circle on Black

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ADOLPH GOTTLIEB (New York, 1903 – New York, 1974)

ADOLPH GOTTLIEB (New York, 1903 – New York, 1974) I use color in terms of emotional quality, as a vehicle for feeling... feeling is everything I have experienced or thought. Adolph Gottlieb was a prominent American painter and member of the first generation of Abstract Expressionists. Characterized by an idiosyncratic use of abstraction that utilized pictographs, tribal and mythological symbols and with a Surrealism influence. He was born in New York in 1903. He studied at public schools but at the age of 17 he left high school to travel around Europe and decided to be an artist. Gottlieb lived in Paris for six months where he visited The Louvre Museum daily and went to drawing classes at the Academie de la Grande Adolph Gotlieb, 1953 © Arnold Newman Chaumiere. He also spent another year visiting museums and galleries in Berlin, Munich, Vienna, Prague and Dresden, among other major European cities. He returned to New York in 1924. Gottlieb studied at The Art Students League, Parson School of Design, Educational Alliance and other local schools where he met his friends Barnet Newman, both shared a studio, Mark Rothko, John Graham, Milton Avery and Chaim Gross. He began producing works influenced by the stylized figuration of Milton Avery. Interested in Surrealism, Gottlieb’s art became more abstract with the incorporation of ideas as the automatic drawing. He was a founding member of some artists’ groups: “The Ten” (1935), the Federation of American Painters and Sculptors (1939) and New York Artist-Painters (1943). In 1951 Gottlieb is one of the main organizers of the protest that, would give him and his colleagues, the name of "The Irascibles". -

The Inflation of Abstraction | the New Yorker

6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker The Art World The Inflation of Abstraction The Met’s show of Abstract Expressionism wants to remake the canon. By Peter Schjeldahl December 31, 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 1/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker Mark Rothko’s “No. 3,” from 1953, his peak year of miracles. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Courtesy ARS he rst room of “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera,” a wishfully canon- T expanding show of painting and sculpture from the past eight decades, at the Metropolitan Museum, affects like a mighty organ chord. It contains the museum’s two best paintings by Jackson Pollock: “Pasiphaë” (1943), a quaking compaction of https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 2/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker mythological elements named for the accursed mother of the Minotaur, and “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” (1950), a singing orchestration of drips in black, white, brown, and teal enamel—bluntly material and, inextricably, sublime. There are six Pollock drawings, too, and “Number 7” (1952), one of his late, return-to- guration paintings in mostly black on white, of an indistinct but hieratic head. The adjective “epic” does little enough to honor Pollock’s mid-century glory, which anchors the standard art-historical saga of Abstract Expressionism—“The Triumph of American Painting,” per the title of a 1976 book on the subject by Irving Sandler —as a revolution that stole the former thunder of Paris and set a stratospheric benchmark for subsequent artists. -

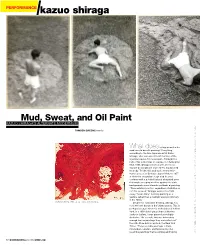

Performance Kazuo Shiraga

PERFORMANCE kazuo shiraga Mud, Sweat, and Oil Paint KAZUO SHIRAGA’S ALTERNATE MODERNIsm. TAMSEN GREENEwords What does rolling around in the mud have to do with painting? Everything, according to the late Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, who was a prominent member of the legendary Gutai Art Association. Although the bulk of his output was on canvas, in Challenging Mud, 1955, Shiraga wrestled with a formless mixture of wall plaster and cement that bruised his body. To him, this and such other perfor- mance pieces as Sanbaso-Super Modern, 1957— in which he swayed on stage clad in a red costume with a pointed hat and elongated arms that made sweeping motions against the dark background—were alternate methods of painting. “There exists my action, regardless of whether or not it is secured,” Shiraga wrote in his 1955 essay “Action Only.” Defining painting as a gesture rather than a medium was revolutionary in the 1950s. Chizensei Kirenji, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS, 51¼ X 63¾ IN. Despite his innovative thinking, Shiraga has not been well known in the United States. This is perhaps because when his work debuted in New York, in a 1958 Gutai group show at Martha Jackson Gallery, it was panned as multiply derivative. “As records, they are interesting enough, but as paintings they are ineffectual,” the critic Dore Ashton wrote in the New York Times. “They resemble paintings in Paris, Amsterdam, London, and Mexico City that resemble paintings that resemble paintings by FROM TOP: THREE IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER; VERVOORDT FOUNDATION COLLECTION. OPPOSITE: BOTH IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER 32 MODERN PAINTERS APRIL 2010 ARTINFO.COM Performance stills from Challenging Mud, third execution. -

San Francisco Art Institute Presents Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT: Janette Andrawes 415.749.4515 [email protected] San Francisco Art Institute Presents Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response First West Coast Survey Exhibition of Avant-Garde, Postwar Japanese Art Movement Features Site-Specific Contemporary Responses to Classic Gutai Performative Works Exhibition: Experimental Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Mid-Winter Burning Sun: Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response Curators: John Held, Jr. and Andrew McClintock Venue: Walter and McBean Galleries San Francisco Art Institute 800 Chestnut Street, San Francisco, CA Dates: February 8–March 30, 2013 Media Preview: Friday, February 8, 5:00–6:00 pm Cost: Free and Open to the Public San Francisco, CA (January 9, 2013) — The San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) is proud to announce the first West Coast survey exhibition of Gutai (1954-1972)—a significant avant-garde artist collective in postwar Japan whose overriding directive was: "Do something no one's ever done before." Rejecting the figurative and abstract art of the era, and in an effort to transform the Japanese psyche from wartime regimentation to independence of thought, Gutai artists fulfilled their commitment to innovative practices by producing art through concrete, performative actions. With a diverse assembly of historical and contemporary art, including several site- specific performances commissioned exclusively for SFAI, Experimental Exhibition of Modern Art to Challenge the Mid-Winter Burning Sun: Gutai Historical Survey and Contemporary Response creates a dialogue with classic Gutai works while demonstrating the lasting significance and radical energy of this movement. This exhibition showcases North American, neo-conceptualist artists' responses to groundbreaking Gutai performances; dozens of original paintings, video, photographs, and ephemera from private collections; and an expansive collection of Mail Art from more than 30 countries. -

Downloaded Or Projected for Classroom Use

FEBUARY 15, 2013–MAY 8, 2013 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum Teacher Resource Unit A NOTE TO TEACHERS Gutai: Splendid Playground is the first U.S. museum retrospective exhibition ever devoted to Gutai, the most influential artists’ collective and artistic movement in postwar Japan and among the most important international avant-garde movements of the 1950s and 1960s. The exhibition aims to demonstrate Gutai’s extraordinary range of bold and innovative creativity; to examine its aesthetic strategies in the cultural, social, and political context of postwar Japan and the West; and to further establish Gutai in an expanded history of modern art. Organized thematically and chronologically to explore Gutai’s unique approach to materials, process, and performativity, this exhibition explores the group’s radical experimentation across a range of mediums and styles, and demonstrates how individual artists pushed the limits of what art could be and mean in a post-atomic age. The range includes painting (gestural abstraction and post-constructivist abstraction), conceptual art, experimental performance and film, indoor and outdoor installation art, sound art, mail art, interactive or “playful” art, light art, and kinetic art. The Guggenheim show comprises some 120 objects by twenty-five artists on loan from major museum and private collections in Japan, the United States, and Europe, and features both iconic and lesser-known Gutai works to present a rich survey reflecting new scholarship, especially on so-called “second phase” works dating from 1962–72. Gutai: Splendid Playground is organized by Ming Tiampo, Associate Professor of Art History, Carleton University, and Alexandra Munroe, Samsung Senior Curator of Asian Art, Guggenheim Museum. -

The First Gutai Exhibition I N Japan Marks the Dissemination Of

1955a The first Gutai exhibition in Japan marks the dissemination of modernist art through the media and its reinterpretation by artists outside the United States and Europe, also exemplified by the rise of the Neoconcretist group in Brazil. n the fifth issue of the journal Gutai, published in October 1956, painter-his works then were competent yet rather provincial .l this brief statement appeared: 'The US artist jackson Pollock, versions of European postwar abstraction. It is not so much his whom we highly esteemed, has passed away all too early in a road own art as his independence of mind, his defianceof bureaucracy, accident, and we are deeply touched. B. H. Friedman who was close his willingness to seize the opportunity of a clean slate afforded by to him, and who sent us the news of this death, wrote: 'When the historical situation of postwar japan, and his encouragements recently I looked through Pollock's library, I discovered issues two to be as radical as possible that explain the attraction he exerted on and three of Gutai. I was told that Pollock was an enthusiastic artists who were a generation younger. His interest in perfor- disciple of the Gutai, fo r in it he had recognized a vision and a mance and in the theater-the only domain where he was as CD reali� close to his own.' " This last sentence is subject to doubt, to innovative as the other members of Gutai-also played a major U1 0 say the least (was Friedman excessively polite, was his letter tam role in defining the group's activity. -

Abstract Expressionism Annenberg Courtyard: David Smith 1

Large Print Abstract Expressionism Annenberg Courtyard: David Smith 1. Introduction and Early Work Do not remove from gallery Audio tour Main commentary Descriptive commentary 1 Jackson Pollock, ‘Male and Female’ 1 Abstract Expressionism Main Galleries: 24 September 2016 – 2 January 2017 Contents Page 4 Annenberg Courtyard: David Smith Page 6 List of works Page 9 1. Introduction and Early Work Page 12 List of works ExhibitionLead Sponsor Lead Sponsor Supported by The production of RA large print guides is generously supported by Robin Hambro 2 Burlington House 1 2 4 3 You are in the Annenberg Courtyard 3 Annenberg Courtyard Abstract Expressionism David Smith b. 1906, Decatur, IN – d. 1965, South Shaftsbury, VT As the key first-generation Abstract Expressionist sculptor, David Smith created an output that spanned a great range of themes and effects. The works here represent four of the climactic series that Smith produced from 1956 until his untimely death in 1965. They encompass rising forms that evoke the human presence (albeit in abstract terms) and others in which a more stern character, by turns mechanistic or architectonic, prevails. 4 The Courtyard display seeks to recreate the spirit of Smith’s installations in his fields at Bolton Landing in upstate New York. There, not only did each sculpture enter into a silent dialogue with others, but they also responded to the space and sky around them. Thus, for example, the dazzling stainless-steel surfaces of the ‘Cubi’ answer to the brooding, inward darkness of ‘Zig III’. Often, Smith’s imagery and ideas parallel concerns seen throughout Abstract Expressionism in general. -

Adolph Gottlieb Classic Paintings

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Adolph Gottlieb Classic Paintings 510 West 25th Street March 1 – April 13, 2019 Opening Reception: Thursday, February 28, 6 – 8 PM New York—Pace Gallery is honored to present an exhibition of paintings by Adolph Gottlieb (1903 – 1974), a leader of the New York School and seminal force in abstraction. Drawing together works from the Adolph and Esther Gottlieb Foundation alongside a number of paintings on loan from major institutions—including The Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Jewish Museum, Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Walker Art Center, and Princeton University Art Museum, among others—Adolph Gottlieb: Classic Paintings features over 20 large-scale paintings created by Gottlieb from the mid-1950s until his death in 1974. The exhibition will be on view at 510 West 25th Street from March 1 – April 13, 2019, with an opening reception on Thursday, February 28 from 6 – 8 PM. A full-color catalogue with a new essay by Dr. Kent Minturn accompanies the exhibition. The exhibition focuses on two major images from Gottlieb’s later work: Bursts and Imaginary Landscapes. In the early 1950s, Gottlieb began to further pare down his compositions resulting in horizontally-oriented Imaginary Landscape paintings, such as the 7-by-12-foot work Groundscape (1956) included in this exhibition. Observing that the “all-over” motif that he had begun to utilize in 1941 had become a common element of American abstract painting, Gottlieb radically compressed his image to the mutually-opposing dual registers of the Imaginary Landscape. In these paintings, the composition is divided into an upper and lower horizontal area, each one characterized by different painting techniques to yield seemingly opposing emotional material, while the paintings ultimately balance as a complex single image. -

Art Review Asia Autumn 2019 Low

Suki Seokyeong Kang Suki Seokyeong The Theatre of Objects of Theatre The Lickety and Split often met each other in the land of Wonton Autumn 2019 Previewed Wu Tsang Naeem Mohaiemen What Lies Within: Centre of the Centre Gropius Bau, Berlin Experimenter, Kolkotta Museum of Contemporary Through 12 January Through 5 November Art and Design, Manila Through 1 December Karen Knorr Micro Era. Media Art from China Sundaram Tagore, Singapore Kulturforum, Berlin Istanbul Biennial 21 September–16 November Through 26 January Various venues, Istanbul Through 10 November Nikhil Chopra rifts: Thai contemporary artistic Metropolitan Museum of Art, practices in transition Nam June Paik New York Bangkok Art and Culture Centre Tate Modern, London 12 – 20 September Through 24 November 17 October – 9 February Sita and Rama: The Ramayana Phantom Plane: Cyberpunk The Herstory of Abstraction in East Asia in Indian Painting in the Year of the Future Taipei Fine Arts Museum Metropolitan Museum of Art, Tai Kwun Centre for Heritage & Arts, Through 27 October New York Hong Kong Through 23 August 2020 4 October – 4 January Clapping with Stones: Art and Acts of Resistance A distant relative Liquefied Sunshine | Force Majeure Rubin Museum, New York Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington Blindspot Gallery, Hong Kong Through 6 January Through 28 September Through 2 November Genieve Figgis kaws Xiao Lu Almine Rech, Shanghai National Gallery of Victoria, 10 Chancery Lane, Hong Kong 20 September – 19 October Melbourne Through 5 October 20 September – 13 April Atsuko Tanaka Ryoji Ikeda Moderna Museet, Stockholm Philip-Lorca diCorcia Taipei Fine Arts Museum Through 16 February David Zwirner, Hong Kong Through 17 November Through 12 October 4 The Combat of Rama and Ravana, India, Coromandel Coast, late-eighteenth century, painted and mordant-dyed cotton, 87 × 539 cm. -

The Avant Garde Festivals. and Now, Shea Stadium

by Stockhausen for American performance. Moorman's reac- Judson Hall on 57th Street and included jazz, electronic and even the auspicious begin- nonsonic work, as well as more traditional compositions . The idea tion, "What's a Nam June Paik?", marked the with ning of a partnership that has lasted for over ten years .) The various that music, as a performance art, had promising connections much mediums in were more distinct than is usual in an other art forms ran through the series, as it did through Originale intermedia work (Stockhausen tends to be rather Wagnerian in his the music itself . The inclusion of works by George Brecht, of thinking), but the performance strove for a homogeneous realiza- Sylvano Bussotti, Takehisa Kosugi, Joseph Beuys, Giuseppe . Chiari, Ben Vautier and other "gestural composers" gives some tion dated The 1965 festival was to be the last at Judson Hall . It, too, idea of the heterogeneity of its scope . Cage's works (which early '50s), featured Happenings, including a performance of Cage's open- back to his years at Black Mountain College in the ended Piece. Allan Kaprow's Push Pull turned so ram- along with provocative antecedents by the Futurists, Dadaists and Theater people scavenging in the streets for material to Surrealists, had spawned a generation here, in Europe and in Japan bunctious (with the ruckus) that Judson Hall would have no more. concerned with the possibilities of working between the traditional incorporate into Moorman was not upset; she had been planning a move anyway . categories of the arts-creating not a combination of mediums, The expansive nature of "post-musical" work demanded larger as in a Wagnerian Gesamtkunstwerk where the various arts team spaces-and spaces not isolated from everyday life. -

Labyrinth of the Shadow: History and Alchemy in Adolph Gottlieb's The

Figure 1 - The Prisoners by Adolph Gottlieb, 1947. Labyrinth of the Shadow: History and Alchemy in Adolph Gottlieb’s The Prisoners Michael J. Landauer and Bruce Barnes PART 1 THE PRISONERS, 1947 by ADOLPH GOTTLIEB: A Systematic Symbolic Interpretation by Michael J. Landauer ARAS Connections Issue 3, 2011 I first met this painting at the Waddington-Shiell Gallery in Toronto in 1979. Miriam Shiell had brought The Prisoners over for the season’s opening show from Leslie Waddington’s London Gallery. The Prisoners dominated its space and bowled me over with its larger than life presence. It brooded gloom, spat menace, radiated stubborn hope. I fell in love immediately. In 1945 Gottlieb wrote in the New York Times , “Painting is the making of images. All painters strive for the image but some produce only effigies. This outcome is not determined by the degree of resemblance to natural objects; rather it is by the invention of symbols transcending resemblance that imagery is made possible . If the painter’s conception is realized in the form of an image, we are confronted with a new natural object which has its own life, its own beauty and its own wisdom.” 1 At about the same time, speaking rhetorically about his own art, Gottlieb said “If the origin of painting was the making of marks or poetic signs should we consider the painter an artisan-poet or is he the artisan-architect of a formal structure? Or both?” 2 Gottlieb and Mark Rothko with Barnett Newman’s assistance drafted a letter to Alden Jewell Art Editor at the NYT on June 7, 1943. -

Yoko Ono's Performance Art,” Intersections 10, No

intersections online Volume 10, Number 1 (Winter 2009) Whitney Frank, “Instructions for Destruction: Yoko Ono's Performance Art,” intersections 10, no. 1 (2009): 571-607. ABSTRACT What is currently known as “destruction art” originated in the artistic and cultural work of avantgarde art groups during the 1960s. In the aftermath of World War Two, the threat of annihilation through nuclear conflict and the Vietnam War drastically changed the cultural landscapes and everyday life in the United States, Asia, and Europe. In this context, “destruction art” has been situated as the “discourse of the survivor,” or the method in which the visual arts cope with societies structured by violence and the underlying threat of death. Many artists involved in destruction art at this time were concerned with destroying not just physical objects, but also with performing destruction with various media. By integrating the body into conceptual works rather than literal narratives of violence, artists contested and redefined mainstream definitions of art, social relations and hierarchies, and consciousness. Yoko Ono, who was born in Tokyo in 1933 and began her work as an artist in the late 1950s, addresses destruction through conceptual performances, instructions, and by presenting and modifying objects. Ono’s work is not only vital to understanding the development of the international avant garde, but it is relevant to contemporary art and society. Her attention to the internalization of violence and oppression reflects contemporaneous feminist theory that situates the female body as text and battleground. By repositioning violence in performance work, Ono’s art promotes creative thinking, ultimately drawing out the reality of destruction that remains hidden within the physical and social body.