Yoko Ono's Performance Art,” Intersections 10, No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hédi A. Jaouad. “Limitless Undying Love”: the Ballad of John and Yoko and the Brownings

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revue CMC Review (York University) Hédi A. Jaouad. “Limitless Undying Love”: The Ballad of John and Yoko and the Brownings. Manchester Center, Vermont: Shires Press, 2015. 132 pp. Hédi A. Jaouad is a distinguished scholar known for his expertise on Francophone North African (Maghrebi) literature. Professor of French and Francophone literature at Skidmore College, Saratoga Springs, New York, he is the Editor of CELAAN, the leading North American journal focusing on North African literature and language. He is also interested in Victorian literature, with particular concentration on Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning, on whom he published a previous book, The Brownings’ Shadow at Yaddo (2014). However, his current book, “Limitless Undying Love”: The Ballad of John and Yoko and the Brownings, shows a whole other side to his scholarship, for it links the Brownings to those icons of contemporary popular culture, John Lennon and Yoko Ono. This is a concise, economical little study (132 pp.), but it manages, in brief compass, to be pluridisciplinary, building bridges between poetry, music, and painting. As he modestly proclaims, it shows “his passion for more than one liberal art” (7). The title, “Limitless Undying Love,” comes from a late John Lennon song, “Across the Universe.” Hédi Jaouad reminds us that the titular “Ballad” applies to both poetry and music. He compares what he has called 19th-century “Browningmania” to 20th-century “Beatlemania,” both of which spread to North America in what has been popularly described as a “British Invasion.” Lest the reader assume Jaouad is only tracing coincidental parallels, he makes it clear from the outset that John and Yoko actually saw themselves as reincarnations of the Brownings, and consciously exploited the similarities in their lives and careers. -

Statement on Intermedia

the Collaborative Reader: Part 3 Statement on Intermedia Dick Higgins Synaesthesia and Intersenses Dick Higgins Paragraphs on Conceptual Art/ Sentences on Conceptual Art Sol Lewitt The Serial Attitude Mel Bochner The Serial Attitude – Mel Bochner Tim Rupert Introduction to the Music of John Cage James Pritchett In the Logician's Voice David Berlinski But Is It Composing? Randall Neal The Database As a Genre of New Media Lev Manovich STATEMENT ON INTERMEDIA Art is one of the ways that people communicate. It is difficult for me to imagine a serious person attacking any means of communication per se. Our real enemies are the ones who send us to die in pointless wars or to live lives which are reduced to drudgery, not the people who use other means of communication from those which we find most appropriate to the present situation. When these are attacked, a diversion has been established which only serves the interests of our real enemies. However, due to the spread of mass literacy, to television and the transistor radio, our sensitivities have changed. The very complexity of this impact gives us a taste for simplicity, for an art which is based on the underlying images that an artist has always used to make his point. As with the cubists, we are asking for a new way of looking at things, but more totally, since we are more impatient and more anxious to go to the basic images. This explains the impact of Happenings, event pieces, mixed media films. We do not ask any more to speak magnificently of taking arms against a sea of troubles, we want to see it done. -

All These Post-1965 Movements Under the “Conceptual Art” Umbrella

All these post-1965 movements under the “conceptual art” umbrella- Postminimalism or process art, Site Specific works, Conceptual art movement proper, Performance art, Body Art and all combinations thereof- move the practice of art away from art-as-autonomous object, and art-as-commodification, and towards art-as-experience, where subject becomes object, hierarchy between subject and object is critiqued and intersubjectivity of artist, viewer and artwork abounds! Bruce Nauman, Live-Taped Video Corridor, 1970, Conceptual Body art, Postmodern beginning “As opposed to being viewers of the work, once again they are viewers in it.” (“Subject as Object,” p. 199) http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9IrqXiqgQBo A Postmodern beginning: Body art and Performance art as critique of art-as-object recap: -Bruce Nauman -Vito Acconci focus on: -Chris Burden -Richard Serra -Carolee Schneemann - Hannah Wilke Chapter 3, pp. 114-132 (Carolee Schneemann and Hannah Wilke, First Generation Feminism) Bruce Nauman, Bouncing Two Balls Between the Floor and Ceiling with Changing Rhythms, 1967-1968. 16mm film transferred to video (black and white, sound), 10 min. Body art/Performance art, Postmodern beginning- performed elementary gestures in the privacy of his studio and documented them in a variety of media Vito Acconci, Following Piece, 1969, Body art, Performance art- outside the studio, Postmodern beginning Video documentation of the event Print made from bite mark Vito Acconci, Trademarks, 1970, Body art, Performance art, Postmodern beginning Video and Print documentation -

Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968

Trinity College Trinity College Digital Repository Resist Newsletters Resist Collection 2-2-1968 Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968 Resist Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter Recommended Citation Resist, "Resist Newsletter, Feb. 2, 1968" (1968). Resist Newsletters. 4. https://digitalrepository.trincoll.edu/resistnewsletter/4 a call to resist illegitimate authority .P2bruar.1 2 , 1~ 68 -763 Maasaohuaetta A.Tenue, RH• 4, Caabrid«e, Jlaaa. 02139-lfewaletter I 5 THE ARRAIGNMENTS: Boston, Jan. 28 and 29 Two days of activities surrounded the arraignment for resistance activity of Spock, Coffin, Goodman, Ferber and Raskin. On Sunday night an 'Interfaith Service for Consci entious Dissent' was held at the First Church of Boston. Attended by about 700 people, and addressed by clergymen of the various faiths, the service led up to a sermon on 'Vietnam and Dissent' by Rev. William Sloane Coffin. Later that night, at Northeastern University, the major event of the two days, a rally for the five indicted men, took place. An overflow crowd of more than 2200 attended the rally,vhich was sponsored by a broad spectrum of organizations. The long list of speakers included three of the 'Five' - Spock (whose warmth, spirit, youthfulness, and toughness clearly delight~d an understandably sympathetic and enthusiastic aud~ence), Coffin, Goodman. Dave Dellinger of Liberation Magazine and the National Mobilization Co11111ittee chaired the meeting. The other speakers were: Professor H. Stuart Hughes of Ha"ard, co-chairman of national SANE; Paul Lauter, national director of RESIST; Bill Hunt of the Boston Draft Resistance Group, standing in for a snow-bound liike Ferber; Bob Rosenthal of Harvard and RESIST who announced the formation of the Civil Liberties Legal Defense Fund; and Tom Hayden. -

Intermedia Dick Higgins, Hannah Higgins

Intermedia Dick Higgins, Hannah Higgins Leonardo, Volume 34, Number 1, February 2001, pp. 49-54 (Article) Published by The MIT Press For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/19618 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] S A Y N N D E S I Intermedia T N H T E E S R 8 S I E A N S Dick Higgins E with an Appendix by Hannah Higgins S 1965 an institution, however. It is absolutely natural to (and inevi- Much of the best work being produced today seems to fall be- table in) the concept of the pure medium, the painting or tween media. This is no accident. The concept of the separa- precious object of any kind. That is the way such objects are tion between media arose in the Renaissance. The idea that a marketed since that is the world to which they belong and to painting is made of paint on canvas or that a sculpture should which they relate. The sense of “I am the state,” however, will not be painted seems characteristic of the kind of social shortly be replaced by “After me the deluge,” and, in fact, if thought—categorizing and dividing society into nobility with the High Art world were better informed, it would realize that its various subdivisions, untitled gentry, artisans, serfs and land- the deluge has already begun. less workers—which we call the feudal conception of the Great Who knows when it began? There is no reason for us to go Chain of Being. -

Kristine Stiles

Concerning Consequences STUDIES IN ART, DESTRUCTION, AND TRAUMA Kristine Stiles The University of Chicago Press Chicago and London KRISTINE STILES is the France Family Professor of Art, Art Flistory, and Visual Studies at Duke University. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 2016 by Kristine Stiles All rights reserved. Published 2016. Printed in the United States of America 24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 12345 ISBN13: 9780226774510 (cloth) ISBN13: 9780226774534 (paper) ISBN13: 9780226304403 (ebook) DOI: 10.7208/chicago/9780226304403.001.0001 Library of Congress CataloguinginPublication Data Stiles, Kristine, author. Concerning consequences : studies in art, destruction, and trauma / Kristine Stiles, pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 9780226774510 (cloth : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226774534 (paperback : alkaline paper) — ISBN 9780226304403 (ebook) 1. Art, Modern — 20th century. 2. Psychic trauma in art. 3. Violence in art. I. Title. N6490.S767 2016 709.04'075 —dc23 2015025618 © This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper). In conversation with Susan Swenson, Kim Jones explained that the drawing on the cover of this book depicts directional forces in "an Xman, dotman war game." The rectangles represent tanks and fortresses, and the lines are for tank movement, combat, and containment: "They're symbols. They're erased to show movement. 111 draw a tank, or I'll draw an X, and erase it, then redraw it in a different posmon... -

The Inflation of Abstraction | the New Yorker

6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker The Art World The Inflation of Abstraction The Met’s show of Abstract Expressionism wants to remake the canon. By Peter Schjeldahl December 31, 2018 https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 1/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker Mark Rothko’s “No. 3,” from 1953, his peak year of miracles. © 1998 Kate Rothko Prizel & Christopher Rothko / Courtesy ARS he rst room of “Epic Abstraction: Pollock to Herrera,” a wishfully canon- T expanding show of painting and sculpture from the past eight decades, at the Metropolitan Museum, affects like a mighty organ chord. It contains the museum’s two best paintings by Jackson Pollock: “Pasiphaë” (1943), a quaking compaction of https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/01/07/the-inflation-of-abstraction 2/8 6/10/2019 The Inflation of Abstraction | The New Yorker mythological elements named for the accursed mother of the Minotaur, and “Autumn Rhythm (Number 30)” (1950), a singing orchestration of drips in black, white, brown, and teal enamel—bluntly material and, inextricably, sublime. There are six Pollock drawings, too, and “Number 7” (1952), one of his late, return-to- guration paintings in mostly black on white, of an indistinct but hieratic head. The adjective “epic” does little enough to honor Pollock’s mid-century glory, which anchors the standard art-historical saga of Abstract Expressionism—“The Triumph of American Painting,” per the title of a 1976 book on the subject by Irving Sandler —as a revolution that stole the former thunder of Paris and set a stratospheric benchmark for subsequent artists. -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

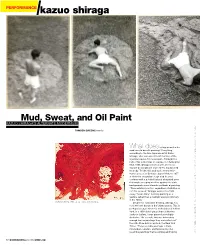

Performance Kazuo Shiraga

PERFORMANCE kazuo shiraga Mud, Sweat, and Oil Paint KAZUO SHIRAGA’S ALTERNATE MODERNIsm. TAMSEN GREENEwords What does rolling around in the mud have to do with painting? Everything, according to the late Japanese artist Kazuo Shiraga, who was a prominent member of the legendary Gutai Art Association. Although the bulk of his output was on canvas, in Challenging Mud, 1955, Shiraga wrestled with a formless mixture of wall plaster and cement that bruised his body. To him, this and such other perfor- mance pieces as Sanbaso-Super Modern, 1957— in which he swayed on stage clad in a red costume with a pointed hat and elongated arms that made sweeping motions against the dark background—were alternate methods of painting. “There exists my action, regardless of whether or not it is secured,” Shiraga wrote in his 1955 essay “Action Only.” Defining painting as a gesture rather than a medium was revolutionary in the 1950s. Chizensei Kirenji, 1961. OIL ON CANVAS, 51¼ X 63¾ IN. Despite his innovative thinking, Shiraga has not been well known in the United States. This is perhaps because when his work debuted in New York, in a 1958 Gutai group show at Martha Jackson Gallery, it was panned as multiply derivative. “As records, they are interesting enough, but as paintings they are ineffectual,” the critic Dore Ashton wrote in the New York Times. “They resemble paintings in Paris, Amsterdam, London, and Mexico City that resemble paintings that resemble paintings by FROM TOP: THREE IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER; VERVOORDT FOUNDATION COLLECTION. OPPOSITE: BOTH IMAGES, AMAGASAKI CULTURAL CENTER 32 MODERN PAINTERS APRIL 2010 ARTINFO.COM Performance stills from Challenging Mud, third execution. -

THE HANDBOOK Your South Beach Success Starts Here!

THE HANDBOOK Your South Beach Success Starts Here! Instructions, food lists, recipes and exercises to lose weight and get into your best shape ever CONTENTS HOW TO USE THIS HANDBOOK You’ve already taken the biggest step: committing to losing weight and learning to live a life of strength, energy PHASE 1 and optimal health. The South Beach Diet will get you there, and this handbook will show you the way. The 14-Day Body Reboot ....................... 4 The goal of the South Beach Diet® program is to help Diet Details .................................................................6 you lose weight, build a strong and fit body, and learn to Foods to Enjoy .......................................................... 10 live a life of optimal health without hunger or deprivation. Consider this handbook your personal instruction manual. EXERCISE: It’s divided into the three phases of the South Beach Beginner Shape-Up: The Walking Workouts ......... 16 Diet® program, color-coded so it’ll be easy to locate your Walking Interval Workout I .................................... 19 current phase: Walking Interval Workout II .................................. 20 PHASE 1 PHASE 2 PHASE 3 10-Minute Stair-Climbing Interval ...........................21 What you’ll find inside: PHASE 2 • Each section provides instructions on how to eat for that specific phase so you’ll always feel confident that Steady Weight Loss ................................. 22 you’re following the program properly. Diet Details .............................................................. 24 • Phases 1 and 2 detail which foods to avoid and provide Foods to Enjoy ......................................................... 26 suggestions for healthy snacks between meals. South Beach Diet® Recipes ....................................... 31 • Phase 2 lists those foods you may add back into your diet and includes delicious recipes you can try on EXERCISE: your own that follow the healthy-eating principles Beginner Body-Weight Strength Circuit .............. -

Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street Into 'Theatre,' Circa 1964 Tokyo

Performance Paradigm 2 (March 2006) Off Museum! Performance Art That Turned the Street into ‘Theatre,’ Circa 1964 Tokyo Midori Yoshimoto Performance art was an integral part of the urban fabric of Tokyo in the late 1960s. The so- called angura, the Japanese abbreviation for ‘underground’ culture or subculture, which mainly referred to film and theatre, was in full bloom. Most notably, Tenjô Sajiki Theatre, founded by the playwright and film director Terayama Shûji in 1967, and Red Tent, founded by Kara Jûrô also in 1967, ruled the underground world by presenting anti-authoritarian plays full of political commentaries and sexual perversions. The butoh dance, pioneered by Hijikata Tatsumi in the late 1950s, sometimes spilled out onto streets from dance halls. Students’ riots were ubiquitous as well, often inciting more physically violent responses from the state. Street performances, however, were introduced earlier in the 1960s by artists and groups, who are often categorised under Anti-Art, such as the collectives Neo Dada (originally known as Neo Dadaism Organizer; active 1960) and Zero Jigen (Zero Dimension; active 1962-1972). In the beginning of Anti-Art, performances were often by-products of artists’ non-conventional art-making processes in their rebellion against the artistic institutions. Gradually, performance art became an autonomous artistic expression. This emergence of performance art as the primary means of expression for vanguard artists occurred around 1964. A benchmark in this aesthetic turning point was a group exhibition and outdoor performances entitled Off Museum. The recently unearthed film, Aru wakamono-tachi (Some Young People), created by Nagano Chiaki for the Nippon Television Broadcasting in 1964, documents the performance portion of Off Museum, which had been long forgotten in Japanese art history. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes.