Call of the Wild Ch 1.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shellfish Reefs at Risk

SHELLFISH REEFS AT RISK A Global Analysis of Problems and Solutions Michael W. Beck, Robert D. Brumbaugh, Laura Airoldi, Alvar Carranza, Loren D. Coen, Christine Crawford, Omar Defeo, Graham J. Edgar, Boze Hancock, Matthew Kay, Hunter Lenihan, Mark W. Luckenbach, Caitlyn L. Toropova, Guofan Zhang CONTENTS Acknowledgments ........................................................................................................................ 1 Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Methods .................................................................................................................................... 10 Results ........................................................................................................................................ 14 Condition of Oyster Reefs Globally Across Bays and Ecoregions ............ 14 Regional Summaries of the Condition of Shellfish Reefs ............................ 15 Overview of Threats and Causes of Decline ................................................................ 28 Recommendations for Conservation, Restoration and Management ................ 30 Conclusions ............................................................................................................................ 36 References ............................................................................................................................. -

Excerpts from Popular Books by Jack London the Call of the Wild Chapter I

Excerpts from Popular Books by Jack London The Call of the Wild Chapter I. Into the Primitive “Old longings nomadic leap, Chafing at custom’s chain; Again from its brumal sleep Wakens the ferine strain.” Buck did not read the newspapers, or he would have known that trouble was brewing, not alone for himself, but for every tide-water dog, strong of muscle and with warm, long hair, from Puget Sound to San Diego. Because men, groping in the Arctic darkness, had found a yellow metal, and because steamship and transportation companies were booming the find, thousands of men were rushing into the Northland. These men wanted dogs, and the dogs they wanted were heavy dogs, with strong muscles by which to toil, and furry coats to protect them from the frost. Figure 1: Jack London, 1905. Photo: Public White Fang Domain Chapter I—The Trail of the Meat Dark spruce forest frowned on either side the frozen waterway. The trees had been stripped by a recent wind of their white covering of frost, and they seemed to lean towards each other, black and ominous, in the fading light. A vast silence reigned over the land. The land itself was a desolation, lifeless, without movement, so lone and cold that the spirit of it was not even that of sadness. There was a hint in it of laughter, but of a laughter more terrible than any sadness—a laughter that was mirthless as the smile of the sphinx, a laughter cold as the frost and partaking of the grimness of infallibility. -

Oyster Growers and Oyster Pirates in San Francisco Bay

04-C3737 1/20/06 9:46 AM Page 63 Oyster Growers and Oyster Pirates in San Francisco Bay MATTHEW MORSE BOOKER The author is a member of the history department at North Carolina State University, Raleigh. In the late nineteenth century San Francisco Bay hosted one of the American West’s most valuable fisheries: Not the bay’s native oysters, but Atlantic oysters, shipped across the country by rail and seeded on privately owned tidelands, created private profits and sparked public resistance. Both oyster growers and oyster pirates depended upon a rapidly changing bay ecosystem. Their struggle to possess the bay’s productivity revealed the inqualities of ownership in the American West. An unstable nature and shifting perceptions of San Francisco Bay combined to remake the bay into a place to dump waste rather than to find food. Both growers and pirates disappeared following the collapse of the oyster fishery in the early twentieth century. In 1902 twenty-two-year-old Oakland writer Jack London published his first book, an adventure story for boys. In the novel, London’s boy hero runs away from a comfortable middle-class home to test his mettle in the rough world of the San Francisco waterfront. Plucky but naïve, Joe Bronson soon finds himself sailing down San Francisco Bay in a rickety sloop called the Dazzler, piloted by hard-drinking French Pete and his tough orphan sidekick, the ’Frisco Kid. The Dazzler joins a small fleet of boats congregating in the tidal flats along the eastern shoreline of San Francisco Bay where French Pete orders Joe and the Kid to drag a triangular piece of steel, an oyster dredge, over the muddy bottom. -

Jack London's Superman: the Objectification of His Life and Times

Jack London's superman: the objectification of his life and times Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Kerstiens, Eugene J. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 07/10/2021 19:49:44 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/319012 JACK LONDON'S SUPERMAN: THE OBJECTIFICATION OF HIS LIFE AND TIMES by Eugene J. Kerstiens A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1952 Approved: 7 / ^ ^ Director of Thesis date r TABLE OF OOHTEHTB - : ; : ■ ; ; : . ' . : ' _ pag® IHfRODUOTIOS a » 0 0 o o o » , » » * o a c o 0 0 * * o I FiRT I : PHYSICAL FORGES Section I 2 T M Fzontiez Spirit in- Amerioa 0 - <, 4 Section II s The lew Territories „,< . > = 0,> «, o< 11 Section III? The lew Front!@3?s Romance and ' Individualism * 0.00 0 0 = 0 0 0 13 ; Section IV g Jack London? Ohild of the lew ■ ■ '■ Frontier * . , o » ' <, . * , . * , 15 PART II: IDE0DY1AMI0S Section I : Darwinian Survival Values 0 0 0<, 0 33 Section II : Materialistic Monism . , <, » „= „ 0 41 Section III: Racism 0« « „ , * , . » , « , o 54 Section IV % Bietsschean Power Values = = <, , » 60 eoiOLDsioi o 0 , •0 o 0 0. 0o oa. = oo v 0o0 . ?e BiBLIOSRAPHY 0 0 0 o © © © ©© ©© 0 © © © ©© © ©© © S3 li: fi% O A €> Ft . -

The Call of the Wild Extract

The Call of the Wild and Other Stories The Call of the Wild and Other Stories Jack London Illustrations by Ian Beck ALMA CLASSICS AlmA ClAssiCs an imprint of AlmA books ltd 3 Castle Yard Richmond Surrey TW10 6TF United Kingdom www.almaclassics.com ‘The Call of the Wild’ first published in 1903; ‘Brown Wolf’ first pub- lished in 1906; ‘That Spot’ first published in 1908; ‘To Build a Fire’ first published in 1908 This edition first published by Alma Classics in 2020 Cover and inside illustrations © Ian Beck, 2020 Extra Material © Alma Books Ltd Printed in Great Britain by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon CR0 4YY isbn: 978-1-84749-844-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or other- wise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not be resold, lent, hired out or otherwise circulated without the express prior consent of the publisher. Contents The Call of the Wild and Other Stories 1 The Call of the Wild 3 Brown Wolf 107 That Spot 127 To Build a Fire 139 Notes 159 Extra Material for Young Readers 161 The Writer 163 The Book 165 The Characters 167 Other Animal Adventure Stories 169 Test Yourself 172 Glossary 175 The Call of the Wild and Other Stories THE CALL OF THE WILD 1 Into the Primitive Old longings nomadic leap, Chafing at custom’s chain; Again from its brumal sleep Wakens the ferine strain.* uCk did not reAd the newspapers, or he would B have known that trouble was brewing – not alone for himself, but for every tidewater dog, strong of muscle and with warm, long hair, from Puget Sound to San Diego. -

Stony Brook University

SSStttooonnnyyy BBBrrrooooookkk UUUnnniiivvveeerrrsssiiitttyyy The official electronic file of this thesis or dissertation is maintained by the University Libraries on behalf of The Graduate School at Stony Brook University. ©©© AAAllllll RRRiiiggghhhtttsss RRReeessseeerrrvvveeeddd bbbyyy AAAuuuttthhhooorrr... Whalemen’s Song: Lyrics and Masculinity in the Sag Harbor Whalefishery, 1840-1850 A Dissertation Presented by Stephen Nicholas Sanfilippo to The Graduate School in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University May 2010 Copyright by Stephen Nicholas Sanfilippo 2010 Stony Brook University The Graduate School Stephen Nicholas Sanfilippo We, the dissertation committee for the above candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree, hereby recommend acceptance of this dissertation. Dr. Wilbur R. Miller PhD Dissertation Advisor Professor of History Department of History Dr. Donna J. Rilling PhD Chairperson of the Defense Associate Professor of History Department of History Dr. Joel Rosenthal PhD Distinguished Professor of History Department of History Dr. Glenn Gordinier PhD Robert G. Albion Historian Co-Director Munson Institute This dissertation is accepted by the Graduate School Lawrence Martin Dean of the Graduate School ii Abstract of the Dissertation Whalemen’s Song: Lyrics and Masculinity in the Sag Harbor Whalefishery, 1840-1850 by Stephen Nicholas Sanfilippo Doctor of Philosophy in History Stony Brook University 2010 “Whalemen’s Song” is a gender-based examination of conceptions and performances of masculinity among Long Islanders of British ancestry who whaled out of Sag Harbor in the 1840s. Its theoretical basis is that masculinity is cultural and demonstrated in performance, with concepts and performances varying from man to man, between and among groups of men, and in relation to various “others,” depending upon the particulars of a situation, including for whom masculinity is being performed. -

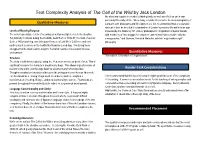

Text Complexity Analysis of the Call of the Wild by Jack London

Text Complexity Analysis of The Call of the Wild by Jack London the story and require the reader to think globally as well as reflect on one’s own personal philosophy of life. Since many consider this novel to be an autobiography of Qualitative Measures London’s own philosophy and life experiences, it is recommended that a reasonable amount of time be devoted to examination of London’s personal life and how he was Levels of Meaning/Purpose: impacted by the following 19th century philosophers: Englishmen Charles Darwin, The novel has multiple levels of meaning as well as multiple levels to the storyline. with his theory of “the struggle for existence” and Herbert Spencer with “only the Set primarily in Alaska during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1896-97, the main character strong survive,” and German, Freidrich Nietsche, with his “might makes right” Buck, a 140 pound dog, was kidnapped from a civilized life in California and sent philosophy. north to learn to survive in the hostile Northland as a sled dog. It is during these struggles that he must learn to adapt to the harsh realities of survival in his new environment. QuaQualitativentitative Measures Measures The lexile is 1010 which is 7.8 grade level. Structure: The story is told chronologically, using the 3rd person omniscient point of view. This is significant because the characters are primarily dogs. This allows a greater sense of realism to the story, and the dogs begin to assume many human qualities. Reader-Task Considerations Though somewhat unconventional because the protagonist is not human, this book can be viewed as a coming of age novel since Buck needs to complete a It is recommended that this novel be used in eighth grade because of the complexity transformation of setting, lifestyle, and personal morality to survive. -

A Study of the Call of the Wild from the Perspective of Greimas' Semiotic Square Theory

ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. 6, No. 8, pp. 1706-1712, August 2016 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0608.27 A Study of The Call of the Wild from the Perspective of Greimas’ Semiotic Square Theory Weiguo Si College of International Studies, Southwest University, China Abstract—Algirdas Julien Greimas is the most influential French structural linguist. He puts forward the profound semiotic square, which has been widely used in the research of literature to reveal the implied meanings and relationship between complex things. The Call of the Wild written by the American naturalistic writer Jack London is his representative work. It has been studied by a lot of scholars from different perspectives since its birth. This thesis applies semiotic square theory, further classifying characters in this novel: Buck is the X; Trafficker is the Anti X; Spitz is the Non X; John is the Non anti X. By the use of the comparative analysis method and the textual close-reading method this thesis analyzes the plot and the deep structure of The Call of the Wild. The result of this thesis is as follows: the relation between Buck and the traffickers is oppression and resistance; the relation between Buck and Spitz is competitor; the relation between Buck and John Thornton is protective and grateful. Through classifying the action elements, readers can see the narrative structure of this novel, which is not stated flatly but with its own unique tortuosity and complexity and it is conducive to deepening their understanding about the artistry and profundity of this novel, and help readers better understand the Superman image of Buck, the main character in The Call of the Wild, and provide them with the effective example in appreciating Jack London’s other literary works. -

Jack London's South Sea Narratives. David Allison Moreland Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1980 Jack London's South Sea Narratives. David Allison Moreland Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Moreland, David Allison, "Jack London's South Sea Narratives." (1980). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 3493. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/3493 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This was produced from a copy of a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “Missing Page(s)”. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure you of complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark it is an indication that the film inspector noticed either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, or duplicate copy. -

Jack London: Master Craftsman of the Short Story

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU Faculty Honor Lectures Lectures 4-14-1966 Jack London: Master Craftsman of the Short Story King Hendricks Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Hendricks, King, "Jack London: Master Craftsman of the Short Story" (1966). Faculty Honor Lectures. Paper 29. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/honor_lectures/29 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Lectures at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Honor Lectures by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. '/. ;>. /71- 33 UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY THIRTY-THIRD FACULTY HONOR LECTURE Jack London: Master Craftsman of the Short Story by KING HENDRICKS Head, Department of English and Journalism THE FACULTY ASSOCIATION UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY LOGAN, UTAH APRIL 1966 Jack London: Master Craftsman of the Short Story N NOVEMBER of 1898 Jack London, aged 22, sold his first short I story, "To the Man on Trail," to Overland Monthly for the sum of $5. Three months later The Black Cat magazine paid him $40 for "A Thousand Deaths." This was the beginning of a writing career that in 17 years was to produce 149 short stories, not including his tramping experiences which he published under the title of The Road, 19 novels, and a number of essays. If all were accumulated and published, they would fill 50 volumes. Besides this, he wrote a number of newspaper articles (war cor respondence, sports accounts, and sociological and socialistic essays), and thousands of letters. -

Gill 1 in the Sea-Wolf (1904) and Call of the Wild (1903), Jack London

Gill 1 In The Sea-Wolf (1904) and Call of the Wild (1903), Jack London depicts what Aristotle would call “the good life” ( eudemonia )—the pursuit of not just “happiness” but “goodness”: how to lead a just, meaningful, virtuous life. At the center of eudemonia is the development of the individual, which includes a broad education designed to enable both individual lives and communities of human beings to flourish. Thus, London remains an exceptional American author who not only exemplifies the literary movement of “Naturalism,” but also who explores philosophical questions. London’s fiction depicts a frightening vision of sociological determinism and, even more importantly, an existential worldview, which prefigures authors such as Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre at the mid-point of the 20 th century. In The Sea-Wolf , Jack London pits the brute force of nature against human culture, both of which present ways of being in the world. On the one hand, nature, as symbolized in Wolf Larsen, the novel’s protagonist, is a blind force, while, on the other hand, culture, as symbolized in Humphrey Van Weyden, the novel’s narrator, appears to be a calculated way of making meaning, a self-serving mechanism that works with human agency. By presenting these two seeming contraries, London works out a philosophical system that combines elements of each realm. The subject of the Sea-Wolf is the search for the Good life, which, according to London, means enduring existential crises and striving to attain a sense of balance. Wolf Larsen, the captain of a schooner named Ghost, and for whom the novel is named, depends on might, acting without compromise. -

Jack London the Call of the Wild It Was Originally Intended Just As a Story to Add Their Own Deeper Fears and Desires

THE Jack London COMPLETE CLASSICS The Call of the Wild UNABRIDGED Read by William Roberts CLASSIC FICTION NA392312D 1 The Call Of The Wild (start) 6:25 2 The Judge was at a meeting... 8:05 3 Four men gingerly carried the crate... 6:05 4 As the days went by, other dogs came... 6:38 5 2: The Law Of Club and Fang 5:30 6 By afternoon, Perrault, who was in a hurry... 7:36 7 Three more huskies were added to the team… 5:54 8 This first theft marked Buck as fit to... 5:07 9 3: The Dominant Primordial Beast 6:19 10 Perrault And Francois, having cleaned out... 7:11 11 At the Pelly one morning... 9:24 12 Seven days from the time they pulled into... 5:58 13 But Spitz, cold and calculating... 6:44 14 4: Who Has Won To Mastership 6:11 15 The general tone of the team picked up... 8:02 16 It was a hard trip, with the mail behind... 7:39 17 5: The Toil of Trace and Trail 6:55 2 18 The dogs sprang against the breast bands... 7:55 19 Late next morning, Buck led... 6:31 20 Mercedes nursed a special grievance – 5:29 21 It was beautiful spring weather… 4:54 22 This was the first time Buck had failed… 4:52 23 6: For the Love of a Man 6:39 24 But in spite of this great love he bore... 8:06 25 Later on, in the fall of the year… 5:58 26 That winter, at Dawson, Buck performed..