Nathalie Dupree's Residence, Charleston, SC Inte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATHALIE DUPREE Charleston, SC

NATHALIE DUPREE Charleston, SC * * * Date: October 7, 2004 Location: Oxford, MS Interviewer: April Grayson Transcription: Shelley Chance, ProDocs Length: 56 minutes Project: SFA Founders Nathalie Dupree – SFA Founder 2 [Begin Nathalie Dupree Interview] 00:00:09 April Grayson: This is April Grayson on October 7, 2004 and I’m interviewing Nathalie Dupree in Oxford, Mississippi. I’m wondering if you could start by telling me your date and place of birth. 00:00:22 Nathalie Dupree: I was born during the very tip of the War in 1939 when my father was stationed in New Jersey. And I think he was stationed in Trenton and I was born in Teaneck. But I remember nothing about New Jersey because we were just there in passing and I think just long enough for me to be born, so but [Laughs] that’s about it. 00:00:53 AG: And where did you grow up? 00:00:54 ND: I grew up in Virginia. I grew up in what was really suburban and country Virginia because at the time that I grew up there were maybe ten houses between Mount Vernon and Highway One and now there are probably 50,000 [Laughs]; I have no idea—there’s a lot. And I grew up in Fairlington just shortly—I mean Shirley Highway and Lee Highway if you know that area, a lot—they hadn’t really been extended very far and it—my father once rode home down Shirley Highway on a bicycle—in a—on a bicycle that he had purchased for me. -

January 2012 from the Adjutant

January 2012 1 I Salute The Confederate Flag; With Affection, Reverence, And Undying Devotion To The Cause For Which It Stands. The Sons of Confederate Veterans is the direct heir of the United Confederate Veterans, and is the oldest hereditary organization for male descendants of Confederate soldiers. Organized at Richmond, Virginia in 1896; the SCV continues to serve as a historical, patriotic, and non-political organization Commander : dedicated to ensuring that a true history of the 1861-1865 period is preserved. Membership David Allen is open to all male descendants of any veteran who served honorably in the Confederate 1st Lieutenant Cdr: John Harris From The Adjutant 2nd Lieutenant Cdr & Adjutant : Gen. Robert E. Rodes Camp 262, Sons of Confederate Veterans, Frank Delbridge will not meet Color Sergeant : on Thursday night, January 12, 2012. Clyde Biggs Chaplain : We will resume our monthly meeting in February. Dr. Wiley Hales Newsletter: Gen. Robert E. Rodes Camp 262, Sons of Confederate Veterans, and James Simms the Gen. Gorgas Chapter of the Military Order of the Stars and Bars will [email protected] hold the 23rd annual Lee-Jackson Banquet at 7 PM January 19th, Website: Brad Smith 2012, at the Circlewood Baptist Church on Loop Road in Tuscaloosa, [email protected] AL. Inside This Issue Our guest speaker will be our Brigade Commander Carl Jones, and 2 Lee-Jackson Dinner the Fifth Alabama Infantry Regiment Band will present a brief musical 3 General Rodes program. The meal will be catered with your choice of chicken or beef. 5 Historical Markers Tickets will be $20 per person. -

John T Transcript Edited

JOHN T EDGE Founding Member and Director of the Southern Foodways Alliance - Oxford, MS * * * Date: April 16, 2010 & February 13, 2012 Locations: Pere Marquette Hotel - New Orleans, LA & The Center for the Study of Southern Culture, University of Mississippi - Oxford, MS Interviewer: Sara Roahen Transcription: Shelley Chance, ProDocs Length: 3 hours, 4 minutes Project: SFA Founders John T Edge—SFA Founder and Director 2 [Begin John T. Interview 1] 00:00:01 Sara Roahen: This is Sara Roahen for the Southern Foodways Alliance. It’s April 16, 2010. I’m in New Orleans, Louisiana, at the Pere Marquette Hotel in downtown New Orleans. And I’m sitting here with John T Edge. For the record, could I get you to say your name, please, and your birth date? 00:00:17 John T Edge: Sure. My name is John T Edge, and I was born December 22, 1962 in Clinton, Georgia. 00:00:27 SR: And could you tell me what your position is currently in relation to the Southern Foodways Alliance? 00:00:31 JTE: I’m the director of the Southern Foodways Alliance and have been since its inception in 1999. 00:00:38 ©Southern Foodways Alliance | www.southernfoodways.org John T Edge—SFA Founder and Director 3 SR: Could you—this is a long—this could be a long answer, but to the best of your ability, could you tell me a little bit about how you got involved with the Southern Foodways Alliance? How that came about? 00:00:52 JTE: Sure. I mean, I’ll have to tell a little bit of my own personal story to say how I got involved in the SFA. -

Fall 2019 Rizzoli Fall 2019

I SBN 978-0-8478-6740-0 9 780847 867400 FALL 2019 RIZZOLI FALL 2019 Smith Street Books FA19 cover INSIDE LEFT_FULL SIZE_REV Yeezy.qxp_Layout 1 2/27/19 3:25 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS RIZZOLI Marie-Hélène de Taillac . .48 5D . .65 100 Dream Cars . .31 Minä Perhonen . .61 Achille Salvagni . .55 Missoni . .49 Adrian: Hollywood Designer . .37 Morphosis . .52 Aēsop . .39 Musings on Fashion & Style . .35 Alexander Ponomarev . .68 The New Elegance . .47 America’s Great Mountain Trails . .24 No Place Like Home . .21 Arakawa: Diagrams for the Imagination . .58 Nyoman Masriadi . .69 The Art of the Host . .17 On Style . .7 Ashley Longshore . .43 Parfums Schiaparelli . .36 Asian Bohemian Chic . .66 Pecans . .40 Bejeweled . .50 Persona . .22 The Bisazza Foundation . .64 Phoenix . .42 A Book Lover’s Guide to New York . .101 Pierre Yovanovitch . .53 Bricks and Brownstone . .20 Portraits of a Master’s Heart For a Silent Dreamland . .69 Broken Nature . .88 Renewing Tradition . .46 Bvlgari . .70 Richard Diebenkorn . .14 California Romantica . .20 Rick Owens Fashion . .8 Climbing Rock . .30 Rooms with a History . .16 Craig McDean: Manual . .18 Sailing America . .25 David Yarrow Photography . .5 Shio Kusaka . .59 Def Jam . .101 Skrebneski Documented . .36 The Dior Sessions . .50 Southern Hospitality at Home . .28 DJ Khaled . .9 The Style of Movement . .23 Eataly: All About Dolci . .40 Team Penske . .60 Eden Revisited . .56 Together Forever . .32 Elemental: The Interior Designs of Fiona Barratt Campbell .26 Travel with Me Forever . .38 English Gardens . .13 Ultimate Cars . .71 English House Style from the Archives of Country Life . -

Austin Conference Issue

WINTER 2014 CULINARY CROSSROADS Austin Conference Issue [ Deep in the Heart of Texas ] IN THIS ISSUE FEATURES WINTER•2 O14 4 Welcome to Texas Preserving for Posterity 5 Dames Across Texas My 95-year old Texas mother Carolyn Cheney was flattered when a Dame at the Austin Conference asked 6-7 Pre-Conference Tours her, “What chapter are you from?” I brought Mom as my guest, but if she could have 8 Keynote Address joined the Dallas Chapter when it was formed in 1984, she 9-11 Sessions would have been 66 at the time. The point is, whatever your age when you become a Dame, you 12-13 Partner Luncheon will always be a Dame (as long as your dues are paid!). 14 Sessions Sadly, some of our charter members have already passed away, and the rest of us aren’t getting any younger. If we 16-17 Chapter Photos don’t preserve our knowledge of the organization for pos- terity, we’ll lose a rich history of women’s culinary progress. 18 Fiesta That brings us to the Quarterly. One aim of your two editors, Susan Slack and me, is to capture LDEI history 20-22 Sessions as it happens. The Quarterly itself is an archive of the organization. Helping us capture that history in this conference issue are Dames from more than 20 different 23 Grande Dame Dinner chapters who reported on all the events and sessions. As you page through this issue, note the bylines to see who they are. Add to them many more Dames who sent in DEPARTMENTS photos, Chapter News, Member Milestones, and other current information. -

Rhythm on the Plate

Rhythm on the Plate The 30th Annual Conference of the International Association of Culinary Professionals New Orleans April 15 - 19, 2008 PROGRAM intErnational assoCiation oF culinary proFEssionals 2 Rhythm on the Plate Table of Contents The 30th Annual Conference of The International Association Welcome from Mayor C. Ray Nagin 4 of Culinary Professionals will explore the strands of celebration and responsibility in our food world. We will celebrate the Greetings from IACP President 5 culture of food, its rhythms and its pleasures, and examine the IACP Board of Directors 6 responsibilities food professionals have to future generations for Conference Host Committee 7 holding and sustaining this vital and precious commodity. IACP Giveback 8 The rhythm of our food derives from the surrounding landscape, Conference Information 10 the cultures and the traditions that give food its beauty, tastes and The Culinary Trust Activities 12 aromas. We all have a desire to be involved, to enjoy each other’s company at table, to unify all people, and a wish to express Conference Sponsors 13 concern for others throughout the world, both consumers and 2008 Scholar-in-Residence 14 that which is consumed, past, present and future. Rhythm Optional Culinary Tours - Tuesday 15 requires an appreciation of pleasure, of the harmony of food, its Conference Agenda - Wednesday 16 inner meaning. A great food experience is the result of an art that conceals art, a wonderful synchronicity of the material and non- Conference Agenda - Thursday 25 material worlds. Practitioners of these life-enhancing skills are Conference Agenda - Friday 29 versed in delivering pleasure through the senses. -

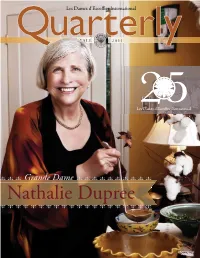

Nathalie Dupree

FALL 2011 Grande Dame Nathalie Dupree IN THIS ISSUE FEATURES 4-5 25th Anniversary LDEI FALL• 2 O 1 1 6-10 Grande Dame Nathalie Dupree Th ere Is Nothing Like a Dame! 11 Member Blogs Nothing makes the earth seem so spacious as to have friends at a distance; they make the latitudes and longitudes. Henry David Th oreau DFV Wines Th ere’s a lot to read about in the FallQuarterly ! We salute the 25th 12-13 anniversary of LDEI, celebrate Nathalie Dupree (Charleston) as our Introduce HandCraft new Grande Dame, and showcase recent events from three chapters: London, Charleston and Washington D.C. Th eQuarterly editor works closely with the members and friends of 14-15 Board Meeting LDEI, investing time in their interests. During my three-year tenure in St. Louis as editor and international board member, it has been a privilege to meet extraordinary Dames from 28 chapters. As a result, two new columns have been added: Th e Global Culinary Post Card, which 16-17 London Dames Host brings Dames closer together around the global dinner table and We- Great Kitchen Clear-Out Belong, the place to share a meaningful excerpt from your personal blog and tell what’s on your mind. It’s also a season of change, as the 2012 board of directors takes the 18-19 Charleston's helm. It’s challenging to manage Quarterly responsibilities with profes- Autumn Affair sional and personal obligations, so in a vote of confi dence, the board of directors invited me to partner with CiCi Williamson (Washington D.C.) as co-editors next year. -

Spring 2013 in THIS ISSUE

SPRING 2013 IN THIS ISSUE “Never doubt that a SPRING•2 O13 FEATURES small group of thoughtful, committed people can change the world. Indeed, it is the only thing that ever has.” - Margaret Mead 4-5 Brock Circle Spring is unfolding before our eyes. In Carolina, curling tendrils Board of Directors 2013 of yellow Jessamine climb over fences and pines, and the irises and 6-9 dogwoods are in full bloom. Plants are ephemeral but the cultiva- tion of philanthropic resources is longer lasting. Th is issue salutes the 9 Quarterly Editors 2013 power and infl uence of women. In the modern lexicon, philanthropy is synonymous with values, vision, passion and responsibility; traits 10-12 Legacy Awards that are shared by members of the Brock Circle. On page 5, Lori Wil- lis (St. Louis) pays tribute to founder Carol Brock (New York) and the growing circle of savvy women whose generous donations will help 13 Denver Board Meeting shape the fi nancial future of LDEI. Get to know the winners of the 2012 Legacy Awards on pages 10-12. 14-15 Global Culinary Postcards Six more “legends” in the making, these impressive young women share with us their internship experiences and future goals. Food Day 2012 Meet the 2013 Board of Directors and our talented Editorial Staff in 16-17 this issue. Each Dame shares a favorite quote from one of our esteemed Grande Dames. Th is year, the organization will bestow the title upon 18 Dames on Television another distinguished woman; nominees will be introduced in the upcoming Summer Quarterly. -

It's ALL Grande

FALL 2015 IT’S ALL GRanDE for LDEI Erin BYERS MURRAY Joan NATHAN Grand Prize Winner in LDEI’s M.F.K. Fisher Grande Dame Award Winner Awards for Excellence in Culinary Writing ALSO INSIDE | NEW CHAPTERS FOR LDEI EDIBLE LONDON TOUR | LDEI BOARD IN MINNESOTA From left: Joan Nathan receiving the 2005 James Beard award for her book The New American Cooking. Horse-drawn carriage ride in Charleston. "Cowheart" tomatoes and other vine-ripened tomatoes at Borough Market in London (see Edible London 2016 tour on page 16). Below: CiCi sitting on a live bull at the 2002 LDEI Conference in San Antonio FROM THE EDITOR H igh Fives! FALL 2 O15 When did milk cost $ 0.80 per gallon? Well, it was in 1976, when the New York Chapter held its grand investiture at the French consulate. That year, the topT V se- IN THIS ISSUE ries was “Happy Days” (set in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, where we still have no chapter), FEATURES and “Rocky” (set in the home of our Phila- delphia Chapter) won the Academy Award for best picture. 4 M.F.K. Fisher Awards In 1986, five chapters (there’s that first number 5) banded together Contest Winners to form LDEI. In 2015, we return to that number as five new groups have been granted chapter status. In between, here is LDEI by mul- 9 Charleston Conference tiples of five. Blue List Presidents of the five original chapters—NewY ork (1973), Wash- ington (1981), Chicago (1982), Dallas and Philadelphia (1984), 10 Board Meeting in Minnesota launched LDEI on October 27, 1986, at a gala dinner in the lobby of the New York Daily News building. -

In-Conversation-With-Exceptional

About Monica Bhide I am an engineer-turned-writer based out of Washington, DC. I have been published in many major national and international publications, including Food & Wine, The New York Times, Parents, Cooking Light, Prevention, Health, SELF, Bon Appetit, Saveur, and many more. I wrote a weekly syndicated column for Scripps Howard Media called “Seasonings” and am a frequent contributor to NPR’s Kitchen Window and AARP-The Magazine. My work has garnered numerous accolades, such as my food essays being included in three Best Food Writing anthologies (2005, 2009 and 2010). I have published three cookbooks, the latest being Modern Spice: Inspired Indian Flavors for the Contemporary Kitchen (Simon & Schuster, 2009). My spice app, iSPICE, was just released for Apple products. 2 Table of Contents Introduction 5 Aarti Sequeira, Food Network star 7 Allison Winn Scotch, New York Times best-selling novelist 11 Amanda Hesser, co-creator of the revolutionary site Food 52 15 Joan Nathan, best-selling cookbook author 19 Corinne Trang, award-winning cookbook author 22 Andrea King Collier, award-winning author and essayist 27 Andrea Nguyen, best-selling cookbook author 31 Carla Hall, co-host, ABC’s The Chew 34 Camille Noe Pagán, debut novelist and longtime Professional writer 40 Clotilde Dusoulier, best-selling cookbook author and blogger 44 Heidi Swanson, best-selling cookbook author and blogger 48 Daisy Martinez, Food Network star 51 Dana Cowin, editor-in-chief, Food & Wine magazine 55 Dorie GreensPan, legendary cookbook author 58 Elise Bauer, -

So U Ther N Co Ok

$60.00 U.S. THIS LIMITED-PRINTING, SPECIAL EDITION OF Mastering the Mastering the Art of SPECIAL EDITION Mastering the Art of has authored 14 cookbooks, three NATHALIE DUPREE Art SOUTHERN of which have won James Beard Awards. She has hosted LIMITED PRINTING WITH SIGNED AND NUMBERED BOOKPLATE more than 300 national and international cooking COOKING shows. She is past president of International Association of of Culinary Professionals, founder and board member SOUTHERN is prefaced with sixteen pages celebrating of Southern Foodways, and founder and co-president of SOUTHERN SOUTHERN Nathalie Dupree, leading up to the occasion of two chapters of Les Dames d’Escoffier. She was the her 80th birthday. Essays by coauthor Cynthia founding president of the Charleston Wine and Food COOKING Graubart and Chef Virginia Willis spotlight Festival. She has been inducted into the James Beard Ms. Dupree’s career and singular influence on Foundation’s Who’s Who of Food and Beverage in COOKING Southern cooking over the past fifty years. America. Along with Mastering the Art of Southern A selection of personal photographs highlight Cooking, her book New Southern Cooking was selected Nathalie’s life and career. for the 2017 Southern Living 100 Best Cookbooks of All Time. She lives in Charleston, South Carolina. n this James Beard Award–winning cookbook, Nathalie Dupree and Cynthia Graubart reveal the CYNTHIA GRAUBART is a James Beard Award– winning cookbook author, cooking teacher, and former Iessence of food that delights, entices, and satisfies, cooking show television producer. She has authored celebrating the “Mother Cuisine” of American cooking eight cookbooks, among them Southern Biscuits (with with more than 750 recipes and 650 variations. -

SEATTLE CONFERENCE ISSUE on the Cover: Seattle Chapter

WINTER 2019 SEATTLE CONFERENCE ISSUE On the cover: Seattle Chapter. Front row, L to R: Jerilyn Brusseau, Cathy Conner, Catherine Hazen, Karen Binder, Sheri Wetherell, Jamie Peha, Patricia Gelles, Beverly Gruber, Lisa Nakamura, Pam Montgomery. Back row, L to R: Katherine Kehrli, Marcia Sisley- Berger, JoAnne Naganawa, Alison Leber (behind), Jane Morimoto, Kate Ruffing, Nancy Leson, Bridget Charters, Cynthia Nims, Cheri Bloom, Pascha Scott, Linda Augustine, Martha Marino, Anne Nisbet, Alice Gautsch Foreman, Naomi Kakiuchi. Right: Photo of Marion Nestle and Hayley Matson-Mathes: Lisa Stewart. Other photos: Susan Slack. FROM THE EDITOR Seattle Conference 2018— WINTER 2 O19 An Encore Performance “The creation of a thousand forests is in one acorn.” Ralph Waldo Emerson Bravo, Seattle Chapter, for a Conference well done! The power IN THIS ISSUE of the encore is considerable. Flashback to 2003: Seattle’s first Conference “Gathering on the Rim,” was, by all reports, a terrific FEATURES success. When Abigail Kirsch (NY) and Rosemary Kowalski (San Antonio) tied for the Grande Dame Award, Renie Steves (Dallas) Pre-Conference Tours and Pat Mozersky (San Antonio) issued a bon mot, “doubling your 6 pleasure and doubling your fun!” Over 1,000 Dames belonged to 23 chapters, which included Adelaide, Australia, and an association 11 Leadership Meeting with Le Donne Del Vino—women in Italian wine. (There are cur- rently 42 chapters and a membership of over 2,200 strong.) 12 Salishly Delicious In an encore performance, Seattle brilliantly hosted its second inter- national Conference, “Grey Skies, Bright Ideas,” October 11-14, 2018. M.F.K. Fisher Awards Over 300 registrants attended educational sessions, tours, and saw 13 product displays from LDEI partners who lead in food and beverage industries.