Urso D'abitot

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

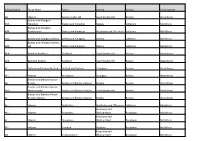

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency

Polling District Parish Ward Parish District County Constitucency AA - <None> Ashton-Under-Hill South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABA - Aldington Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington ABB - Blackminster Badsey and Aldington Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs ABC - Badsey and Aldington Badsey Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs Badsey and Aldington Bowers ABD - Hill Badsey and Aldington Badsey Littletons Mid Worcs ACA - Beckford Beckford Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs ACB - Beckford Grafton Beckford South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs AE - Defford and Besford Besford Defford and Besford Eckington Bredon West Worcs AF - <None> Birlingham Eckington Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AH - Bredon Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AHA - Westmancote Bredon and Bredons Norton South Bredon Hill Bredon West Worcs Bredon and Bredons Norton AI - Bredons Norton Bredon and Bredons Norton Bredon Bredon West Worcs AJ - <None> Bretforton Bretforton and Offenham Littletons Mid Worcs Broadway and AK - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AL - <None> Broadway Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs AP - <None> Charlton Fladbury Broadway Mid Worcs Broadway and AQ - <None> Childswickham Wickhamford Broadway Mid Worcs Honeybourne and ARA - <None> Bickmarsh Pebworth Littletons Mid Worcs ARB - <None> Cleeve Prior The Littletons Littletons Mid Worcs Elmley Castle and AS - <None> Great Comberton Somerville -

7.10 Weeklyplanningapplications

PLANNING APPLICATIONS REGISTERED Weekly list for 12/10/2020 to 16/10/2020 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order The following list of applications will either be determined by the Council's Planning Committee or the Director of Planning and Infrastructure under the Councils adopted Scheme of Delegation. Where a case is listed as being a delegated matter, this is a preliminary view only, and under certain circumstances, the case may be determined by the Planning Committee. Should you require further information please contact the case officer. Application No: 20/02175/HP Location : Hornsfield Nurseries, Penponds, Willersey Road, Badsey, WR11 7HB Proposal : Erection of oak framed timber cabin to provide ancillary accommodation incidental to the residential enjoyment of the main dwelling "Penponds" Date Valid : 07/10/2020 Expected Decision Level : Delegated Applicant : R & L Holt Ltd Agents Name: Mr Peter Bateman Application Type: HP Parish(es) : Badsey Ward(s) : Badsey Ward Case Officer : Hazel Smith Telephone Number : 01684 862342 Email : [email protected] Click On Link to View the planning application : Click Here Application No: 20/02174/LB Location : Coffin Bridge, Hanbury Road, Droitwich Spa Proposal : Install handrail on bridge, repair uneven steps, restrain lateral arch movement by installing anchors, install steel plate to restrain wet abutment, re-pointing brickwork, repair/replace missing bricks. Date Valid : 07/10/2020 Expected Decision Level : Delegated Applicant : Canal & River Trust Agents -

Geoffrey De Mandeville a Study of the Anarchy

GEOFFREY DE MANDEVILLE A STUDY OF THE ANARCHY By John Horace Round CHAPTER I. THE ACCESSION OF STEPHEN. BEFORE approaching that struggle between King Stephen and his rival, the Empress Maud, with which this work is mainly concerned, it is desirable to examine the peculiar conditions of Stephen's accession to the crown, determining, as they did, his position as king, and supplying, we shall find, the master-key to the anomalous character of his reign. The actual facts of the case are happily beyond question. From the moment of his uncle's death, as Dr. Stubbs truly observes, "the succession was treated as an open question." * Stephen, quick to see his chance, made a bold stroke for the crown. The wind was in his favour, and, with a handful of comrades, he landed on the shores of Kent. 2 His first reception was not encouraging : Dover refused him admission, and Canterbury closed her gates. 8 On this Dr. Stubbs thus comments : " At Dover and at Canterbury he was received with sullen silence. The men of Kent had no love for the stranger who came, as his predecessor Eustace had done, to trouble the land." * But "the men of Kent" were faithful to Stephen, when all others forsook him, and, remembering this, one would hardly expect to find in them his chief opponents. Nor, indeed, were they. Our great historian, when he wrote thus, must, I venture to think, have overlooked the passage in Ordericus (v. 110), from which we learn, incidentally, that Canterbury and Dover were among those fortresses which the Earl of Gloucester held by his father's gift. -

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 05/07/2021 to 09/07/2021 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 21/00633/LB Location: The Hay Loft, Northwick Hotel, Waterside, Evesham, WR11 1BT Proposal: Refurbishment of existing rooms including the addition of mezzanine floors and removal of modern ceiling to reveal full height of bay windows. Original lathe and plaster ceiling to be retained. Decision Date: 08/07/2021 Decision: Approval Applicant: Envisage Complete Interiors Agent: Envisage Complete Interiors Flax Furrow Flax Furrow The Old Brickyard The Old Brickyard Kiln Lane Kiln Lane Stratford-upon-avon Stratford-upon-avon CV3T 0ED CV3T 0ED Parish: Evesham Ward: Bengeworth Ward Case Officer: Craig Tebbutt Expiry Date: 12/07/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565323 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 21/00565/TPOA Location: The Grange, Stoney Lane, Earls Common, Himbleton, Droitwich Spa, WR9 7LD Proposal: T1 - Yew to front of property - Carefully reduce crown by 30% removing dead wood and crossing, rubbing branches. Reason: due to location of the tree the roots are causing damage to drive Decision Date: 09/07/2021 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mr A Summerwill Agent: K W Boulton Tree Care Specialists LTD The Grange The Park Stoney Lane Wyre Hill Earls Common Pershore Himbleton WR10 2HT WR9 7LD Parish: Himbleton Ward: Bowbrook Ward Case Officer: Sally Griffiths Expiry Date: 28/04/2021 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565308 Case Officer Email: -

Evesham to Pershore (Via Dumbleton & Bredon Hills) Evesham to Elmley Castle (Via Bredon Hill)

Evesham to Pershore (via Dumbleton & Bredon Hills) Evesham to Elmley Castle (via Bredon Hill) 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 1st walk check 2nd walk check 3rd walk check 19th July 2019 15th Nov. 2018 07th August 2021 Current status Document last updated Sunday, 08th August 2021 This document and information herein are copyrighted to Saturday Walkers’ Club. If you are interested in printing or displaying any of this material, Saturday Walkers’ Club grants permission to use, copy, and distribute this document delivered from this World Wide Web server with the following conditions: • The document will not be edited or abridged, and the material will be produced exactly as it appears. Modification of the material or use of it for any other purpose is a violation of our copyright and other proprietary rights. • Reproduction of this document is for free distribution and will not be sold. • This permission is granted for a one-time distribution. • All copies, links, or pages of the documents must carry the following copyright notice and this permission notice: Saturday Walkers’ Club, Copyright © 2018-2021, used with permission. All rights reserved. www.walkingclub.org.uk This walk has been checked as noted above, however the publisher cannot accept responsibility for any problems encountered by readers. Evesham to Pershore (via Dumbleton and Bredon Hills) Start: Evesham Station Finish: Pershore Station Evesham station, map reference SP 036 444, is 21 km south east of Worcester, 141 km north west of Charing Cross and 32m above sea level. Pershore station, map reference SO 951 480, is 9 km west north west of Evesham and 30m above sea level. -

Bangor University DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY Image and Reality In

Bangor University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Image and Reality in Medieval Weaponry and Warfare: Wales c.1100 – c.1450 Colcough, Samantha Award date: 2015 Awarding institution: Bangor University Link to publication General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 24. Sep. 2021 BANGOR UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF HISTORY, WELSH HISTORY AND ARCHAEOLOGY Note: Some of the images in this digital version of the thesis have been removed due to Copyright restrictions Image and Reality in Medieval Weaponry and Warfare: Wales c.1100 – c.1450 Samantha Jane Colclough Note: Some of the images in this digital version of the thesis have been removed due to Copyright restrictions [i] Summary The established image of the art of war in medieval Wales is based on the analysis of historical documents, the majority of which have been written by foreign hands, most notably those associated with the English court. -

Tewkesbury Abbey Fine and Almost

Tewkesbury Abbey Fine and almost complete example of a Romanesque abbey church Pre-dates Reading. Dedicated in 1121, the year of Reading’s foundation. Look out for anniversary events at Tewksbury in 2021. But some important and interesting links to Reading Both were Benedictine Founder Robert Fitzhamon (honour of Gloucester), friend of Rufus, supported against Robert Curthose. At his death in the New Forest. Then loyal to Henry I – campaigned in Normandy against supporters of Curthose and died doing so in 1107. Fitzhamon’s heiress Mabel married Robert of Gloucester d 1147, the first and most favoured illegitimate son of Henry I, who was a key supporter of his half sister Matilda Granddaughters were coheiresses – but one of them Hawise (or Isabella of Gloucester) married Prince John. Despite annulment, Tewksbury became a royal abbey Later passed to the de Clares. Earls of Gloucester and Hereford. And made their mausoleum Richard III de Clare (grandson) married Joan of Acre, daughter of Edward I Again co heiresses in the early 14th C. the eldest Eleanor married Hugh Despenser the younger, favourite of Edward II, executed 1326. She is instrumental in making Tewksbury into a Despenser mausoleum (significant rebuilding and splendid tombs) Her great grandson Thomas Despenser marries Constance of York granddaughter of Ed III. A strong link with Reading abbey here as she was buried there in 1416 The Despenser line also ended up with an heiress Isabella who married in turn two men called Richard Beauchamp, the first Richard Beauchamp lord Abergavenny a great friend of Henry V who created him earl of Worcester: but Richard died in the French wars in March 1422; and then his half cousin Richard Beauchamp earl of Warwick, also prominent in the wars in France. -

103947 Church House SP.Indd

Church House Elmley Castle, Worcestershire A gracious and beautifully presented former rectory set in over 11 acres on the edge of the village Church House, Elmley Castle, Worcestershire WR10 3HS Broadway 8 miles, Cheltenham 17 miles, Worcester 12 miles, M5 Motorway (Tewkesbury) 12 miles. (All distances are approximate) Features: Reception hall, drawing room, sitting room, dining room, library, living kitchen, boot room and wet room, laundry room, master bedroom with en suite bathroom, five further bedrooms, three further bathrooms (two en suite), cellar Extensive garaging with workshop, garden stores and kennels Landscaped gardens and grounds with lake 6 Stables, secure tack room and hay barn seven paddocks and manège In all about 11.6 acres Location Elmley Castle is a delightful village set on the edge of Bredon Hill, an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. The village has many amenities including a church, primary school, an historic pub and village hall. Its old established cricket team regularly plays on the attractive cricket ground. The market towns of Pershore and Evesham have comprehensive amenities for most everyday needs, whilst Cheltenham has more extensive shopping, leisure and educational facilities. There is an excellent mix of state and private education including schooling in Malvern, Cheltenham and Worcester. Communications are good with access to the M5 at Tewkesbury and a mainline station to London Paddington from Evesham. Property Church House dates from the late 19th century and was formerly the rectory. In the last ten years the property has undergone a significant refurbishment which included taking off a later addition and rebuilding a wing which provides the superb family kitchen/ living area with a glazed garden room. -

8.4 Sheduled Weekly List of Decisions Made

LIST OF DECISIONS MADE FOR 27/04/2020 to 01/05/2020 Listed by Ward, then Parish, Then Application number order Application No: 20/00146/HP Location: 6 Bowers Hill, Badsey, Evesham, WR11 7HG Proposal: Erection of two storey side extension. Decision Date: 01/05/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mr Martin and Mrs Sarah Bent Agent: Mr Martin and Mrs Sarah Bent High Trees High Trees 14 Millend 14 Millend Elmley Castle Elmley Castle Pershore Pershore WR10 3JJ WR10 3JJ Parish: Badsey Ward: Badsey Ward Case Officer: Robert Smith Expiry Date: 01/05/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01386 565328 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Application No: 20/00504/HP Location: Briar Croft, Netherwood Lane, Crowle, Worcester, WR7 4AF Proposal: Two storey extension to side and single storey extension to rear of existing dwelling. Decision Date: 29/04/2020 Decision: Approval Applicant: Mrs Elizabeth Greaves Agent: iK Building Design Ltd Briar Croft 4 Granary Road Netherwood Lane Stoke Heath Crowle Bromsgrove WR7 4AF B60 3QH Parish: Oddingley Ward: Bowbrook Ward Case Officer: Edward Simcox Expiry Date: 04/05/2020 Case Officer Phone: 01684 862346 Case Officer Email: [email protected] Click On Link to View the Decision Notice: Click Here Page 1 of 14 Application No: 19/01355/FUL Location: Field SO 9239, Eckington Road, Bredons Norton Proposal: Change of use from disused land to 5no. pitches for local travellers with 1no. static and 1no. touring caravan per pitch Decision Date: 01/05/2020 -

Violet Click Beetle 12

Species Fact Sheet No. VIOLET CLICK BEETLE 12 What do they look like? The adult is a long thin blue beetle - not violet as the name suggests! How else might I recognise one? The larvae, called ‘wire-worms’, are long thin whitish-coloured grubs that live in a rich mixture of decaying wood, leaf-mould, and bird droppings in the centres of very old trees. What do they eat? The larvae live off the nutrients from the mixture of leaves, decaying Classification wood and bird droppings that they Kingdom: Animalia live in. Phylum: Arthropoda Class: Insecta Where do they live? Order: Coleoptera Very old hollow ash trees, where the Family: Elateridae adults usually breed in the decaying wood and leaf litter of tree cavities. In Genus: Limoniscus Worcestershire the beetle seems to be Species: L. violaceus widespread on Bredon Hill, where it has been found near Bredons Norton, Even Hill, and Elmley Castle Deer Park. As well as the violet click beetle the old trees on Bredon Hill support a large number of different beetles and other insects. We think that the adults remain in the same trees all their lives, only leaving when the tree rots away and no longer provides the conditions they need for breeding. We also think that the adults fly to hawthorn blossom, and there is some suggestion that they could be nocturnal. Why are they special to Worcestershire? The violet click beetle is known to occur in only three places in Britain, of which one is Bredon Hill in Worcestershire. The others are Windsor Forest, Berkshire, and the Gloucestershire Cotswolds. -

KINCAID DECENDED THROUGH the Liweage of EMPEROR

KINCAID DECENDED THROUGH THE LIwEAGE OF EMPEROR CHARLEMANE (742-814) By Ron Lepeska From information provided Clan Kincaia International by Steve Kincaia, San Diego, Microfilm 1750731 item 14. Charlemagne (742-814), who was son of Pepin the Short (714?- 768), ana grandson of Charles Martei "The Hammer" (688-741). Crowned King of the Franks (741), King of Franks and Lombards (774), King of the Holy Roman Empire by Pope Leo III, (800) Pepin, King of Italy and Lombardy, Bernard King of Italy and Lombardy Pepin Pepin ae Seiis ae Vaiois Lady Poppa, married 1st Duke of Normandy William Longsward Richard the Fearless Geoffery, Count of Eu and Brione Gisiebert Crispin, Count of Eu and Brione Richard Fitzgilbert, 1st Earl of Clare, and Chief Justace of England Gilbert ae Tbnebruge, 2nd Earl of Clare Robert Fitzgilbert ae Clair Robert ae Clare Sir Richard ae Clare, Magan Carta surety Baron Richard ae Clair, the Norman-welsh Earl of Pembroke known as Strongbow was enticed by the exiled king MacMurrough of Leister to go to Ireland and fight for him. The offer included the beautiful princess Aoife as his wife and the heirship of the Leister Kingdom. He and his half-brothers, the knights Robert Fitz Stephen & Maurice Fitz Gerald and his Uncle Herve ae Mont Maurice went to Ireland and defeated the Danish king Godred, and ruled Leister. The Irish historians lament that it was impossible to oppose fighters dressed "in one mass of iron". Page 2 Sir Gilbert: ae Clare, Magna Carta surety oaron Isabeia de Clare married Sir Robert ae Brus, Lord of Annanaale Sir Robert de Brus, Lord of Annanaale Robert Bruce, King of the Scots (1274-1329) Daughter, Marjorie married Walter VI, High Steward of Scotland Robert II King Robert, Duke of Albany, Gov. -

Domesday Book and Beyond: Three Essays in the Early History of England Frederic William Maitland

Domesday Book and Beyond: Three Essays in the Early History of England Frederic William Maitland Essay One Domesday Book At midwinter in the year 1085 William the Conqueror wore his crown at Gloucester and there he had deep speech with his wise men. The outcome of that speech was the mission throughout all England of 'barons,' 'legates' or 'justices' charged with the duty of collecting from the verdicts of the shires, the hundreds and the vills a descriptio of his new realm. The outcome of that mission was the descriptio preserved for us in two manuscript volumes, which within a century after their making had already acquired the name of Domesday Book. The second of those volumes, sometimes known as Little Domesday, deals with but three counties, namely Essex, Norfolk and Suffolk, while the first volume comprehends the rest of England. Along with these we must place certain other documents that are closely connected with the grand inquest. We have in the so-called Inquisitio Comitatus Cantabrigiae, a copy, an imperfect copy, of the verdicts delivered by the Cambridgeshire jurors, and this, as we shall hereafter see, is a document of the highest value, even though in some details it is not always very trustworthy.(1*) We have in the so-called Inquisitio Eliensis an account of the estates of the Abbey of Ely in Cambridgeshire, Suffolk and other counties, an account which has as its ultimate source the verdicts of the juries and which contains some particulars which were omitted from Domesday Book.(2*) We have in the so-called Exon Domesday