New Perspectives on Argyll's Rising of 1685

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Passion for Opera the DUCHESS and the GEORGIAN STAGE

A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE A Passion for Opera THE DUCHESS AND THE GEORGIAN STAGE PAUL BOUCHER JEANICE BROOKS KATRINA FAULDS CATHERINE GARRY WIEBKE THORMÄHLEN Published to accompany the exhibition A Passion for Opera: The Duchess and the Georgian Stage Boughton House, 6 July – 30 September 2019 http://www.boughtonhouse.co.uk https://sound-heritage.soton.ac.uk/projects/passion-for-opera First published 2019 by The Buccleuch Living Heritage Trust The right of Paul Boucher, Jeanice Brooks, Katrina Faulds, Catherine Garry, and Wiebke Thormählen to be identified as the authors of the editorial material and as the authors for their individual chapters, has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the authors. ISBN: 978-1-5272-4170-1 Designed by pmgd Printed by Martinshouse Design & Marketing Ltd Cover: Thomas Gainsborough (1727-1788), Lady Elizabeth Montagu, Duchess of Buccleuch, 1767. Portrait commemorating the marriage of Elizabeth Montagu, daughter of George, Duke of Montagu, to Henry, 3rd Duke of Buccleuch. (Cat.10). © Buccleuch Collection. Backdrop: Augustus Pugin (1769-1832) and Thomas Rowlandson (1757-1827), ‘Opera House (1800)’, in Rudolph Ackermann, Microcosm of London (London: Ackermann, [1808-1810]). © The British Library Board, C.194.b.305-307. Inside cover: William Capon (1757-1827), The first Opera House (King’s Theatre) in the Haymarket, 1789. -

Lady Mary, Countess of Caithness, Interceding with Middleton for Permission to Remove Her Father’S Head

Lady Mary, Countess of Caithness, interceding with Middleton for permission to remove her Father’s Head. PREFACE In collecting materials for “The Martyrs of the Bass,” published some time ago in a volume entitled “The Bass Rock,” it occurred to the author, from the various notices he met with of Ladies who were distinguished for their patriotic interest or sufferings in the cause of nonconformity, during the period of the Covenant, and particular- ly, during the period of the persecution, that sketches of the most eminent or best known of these ladies would be neither uninteresting nor unedifying. In undertaking such a work at this distance of time, he is aware of the disadvantage under which he labours, from the poverty of the materials at his disposal, compared with the more abundant store from which a contemporary writer might have executed the same task. He, however, flatters him- self that the materials which, with some industry, he has collected, are not unworthy of being brought to light; the more especially as the female biography of the days of the Covenant, and of the persecution, is a field which has been trodden by no preceding writer, and which may, therefore, be presumed to have something of the fresh- ness of novelty. The facts of these Lives have been gathered from a widely-scattered variety of authorities, both manuscript and printed. From the voluminous Manuscript Records of the Privy Council, deposited in her Majesty’s General Register House, Edinburgh, and from the Wodrow MSS., belonging to the Library of the Faculty of Advocates, Edinburgh, the author has derived much assistance.The former of these documents he was obligingly permitted to consult by William Pitt Dundas, Esq., Depute-Clerk of her Majesty’s Register House. -

Walter Scott's Kelso

Walter Scott’s Kelso The Untold Story Published by Kelso and District Amenity Society. Heritage Walk Design by Icon Publications Ltd. Printed by Kelso Graphics. Cover © 2005 from a painting by Margaret Peach. & Maps Walter Scott’s Kelso Fifteen summers in the Borders Scott and Kelso, 1773–1827 The Kelso inheritance which Scott sold The Border Minstrelsy connection Scott’s friends and relations & the Ballantyne Family The destruction of Scott’s memories KELSO & DISTRICT AMENITY SOCIETY Text & photographs by David Kilpatrick Cover & illustrations by Margaret Peach IR WALTER SCOTT’s connection with Kelso is more important than popular histories and guide books lead you to believe. SScott’s signature can be found on the deeds of properties along the Mayfield, Hempsford and Rosebank river frontage, in transactions from the late 1790s to the early 1800s. Scott’s letters and journal, and the biography written by his son-in-law John Gibson Lockhart, contain all the information we need to learn about Scott’s family links with Kelso. Visiting the Borders, you might believe that Scott ‘belongs’ entirely to Galashiels, Melrose and Selkirk. His connection with Kelso has been played down for almost 200 years. Kelso’s Scott is the young, brilliant, genuinely unknown Walter who discovered Border ballads and wrote the Minstrelsy, not the ‘Great Unknown’ literary baronet who exhausted his phenomenal energy 30 years later saving Abbotsford from ruin. Guide books often say that Scott spent a single summer convalescing in the town, or limit references to his stays at Sandyknowe Farm near Smailholm Tower. The impression given is of a brief acquaintance in childhood. -

Itinerary of Prince Charles Edward Stuart from His

PUBLICATIONS OF THE SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY VOLUME XXIII SUPPLEMENT TO THE LYON IN MOURNING PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART ITINERARY AND MAP April 1897 ITINERARY OF PRINCE CHARLES EDWARD STUART FROM HIS LANDING IN SCOTLAND JULY 1746 TO HIS DEPARTURE IN SEPTEMBER 1746 Compiled from The Lyon in Mourning supplemented and corrected from other contemporary sources by WALTER BIGGAR BLAIKIE With a Map EDINBURGH Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society 1897 April 1897 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................................... 5 A List of Authorities cited and Abbreviations used ................................................................................. 8 ITINERARY .................................................................................................................................................. 9 ARRIVAL IN SCOTLAND .................................................................................................................. 9 LANDING AT BORRADALE ............................................................................................................ 10 THE MARCH TO CORRYARRACK .................................................................................................. 13 THE HALT AT PERTH ..................................................................................................................... 14 THE MARCH TO EDINBURGH ...................................................................................................... -

Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority Headquarters Will Be Closed

Weekly Planning Schedule Week Commencing: 09 December 2019 Week Number: 50 CONTENTS 1 Valid Planning Applications Received 2 Delegated Officer Decisions 3 Committee Decisions 4 Planning Appeals 5 Enforcement Matters 6 Land Reform (Scotland) Act Section 11 Access Exemption Applications 7 Other Planning Issues 8 Byelaw Exemption Applications 9 Byelaw Authorisation Applications Over the festive period, from 24th December 2019 to 3rd January 2020, Loch Lomond and the Trossachs National Park Authority headquarters will be closed. If you submit a planning application or correspondence on or after the 24th December, it will not be receipted until w/c 3rd January 2020. We apologise for any inconvenience this may cause. National Park Authority Planning Staff If you have enquiries about new applications or recent decisions made by the National Park Authority you should contact the relevant member of staff as shown below. If they are not available, you may wish to leave a voice mail message or contact our Planning Information Line on 01389 722024. Telephone Telephone PLANNING SERVICES DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT (01389) (01389) Director of Rural Development and Development & Implementation Manager Planning Bob Cook 722631 Stuart Mearns 727760 Performance and Support Manager Catherine Stewart 727731 DEVELOPMENT PLANNING Planners - Development Management Vivien Emery (Mon - Wed) 722619 Alison Williamson 722610 Development Planning and Caroline Strugnell 722148 Communities Manager Julie Gray (Maternity Leave) 727753 Susan Brooks 722615 Amy Unitt 722606 -

Lord Lauderdale's Garden

John Muir’s Birthplace Fact Sheet Number 3.09 – Lord Lauderdale’s Garden A large mansion house dominates the north end of Dunbar High Street. In John Muir’s day it was just one of the homes owned by the earl of Lauderdale. The bounty of the earl’s garden was one of the young John Muir’s treasured memories of his Dunbar boyhood. The earls had played a leading role in Scotland for centuries before Lauderdale House from the North © ELMS John’s day. James Maitland (1759- 1839), the 8th earl, invested heavily in Dunbar in the 1780s and 1790s. He was a great statesman and served in both houses of parliament, first as an MP and subsequently as a representative peer for Scotland in the Lords. He was renowned for his sympathies for the French Revolution (‘Citizen Maitland’) but despite this taint of radicalism he held many offices of State and was entrusted to negotiate peace between France and Britain in 1806. He kept weather eye on his backyard while pursuing his national career: his sons James and Anthony (later the 9th and 10th earls respectively) served on Dunbar’s town council (along with John’s grandfather David Gilrye), gaining experience for their own parliamentary careers and looking after the family’s local interests. The Maitlands’ household was considerable: in 1841 there were around 25 resident servants looking after the 9th earl and his guests. A further set of ‘outside’ servants probably matched this total – the stable hands, grooms, coachmen and gardeners of the establishment. The gardeners’ main domain was a 5 acre (2 hectare) kitchen garden sheltered behind 15’ high stone walls a little bit to the west of the big house. -

Scotch Malt Whisky Tour

TRAIN : The Royal Scotsman JOURNEY : Scotch Malt Whisky Tour Journey Duration : Upto 5 Days DAY 1 EDINBURG Meet your whisky ambassador in the Balmoral Hotel and enjoy a welcome dram before departure Belmond Royal Scotsman departs Edinburgh Waverley Station and travels north across the Firth of Forth over the magnificent Forth Railway Bridge. Afternoon tea is served as you journey through the former Kingdom of Fife. The train continues east along the coast, passing through Carnoustie, Arbroath and Aberdeen before arriving in the market town of Keith in the heart of the Speyside whisky region. After an informal dinner, enjoy traditional Scottish entertainment by local musicians. DAY 2 KYLE OF LOCHALSH Departing Keith this morning, the train travels west towards Inverness, capital of the Highlands. After an early lunch, disembark in Muir of Ord to visit Glen Ord Distillery, one of the oldest in Scotland. Enjoy a private tour of the distillery as well as a tasting and nosing straight from the cask. Back on board, relax as you enjoy the spectacular views on the way to Kyle of Lochalsh, on one of the most scenic routes in Britain. The line passes Loch Luichart and the Torridon Mountains, which geologists believe were formed before any life began. The train then follows the edge of Loch Carron through Attadale and Stromeferry before reaching the pretty fishing village of Plockton. This evening a formal dinner is served, followed by coffee and liqueurs in the Observation Car. DAY 3 CARRBRIDGE This morning, join a group of keen early-risers on a short, scenic trip to photograph the famous Eilean Donan Castle, one of Scotland’s most iconic sights. -

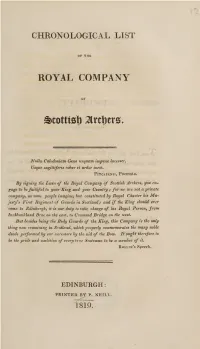

Chronological List of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers

CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF THE ROYAL COMPANY OF 2lrrt)er0. Nulla Caledoniam Gens unquarn impune laces set, Usque sagittiferis rohur et ardor inest. Pitcairnii, Poemata. By signing the Laws of the Royal Company of Scottish Archers, you en¬ gage to he faithful to your King and your Country ; for we are not a private company, as some people imagine, but constituted hy Royal Charter his Ma¬ jesty's First Regiment of Guards in Scotland; and if the King should ever come to Edinburgh, it is our duty to take charge of his Royal Person, from Inchbunkland Brae on the east, to Cramond Bridge on the west. But besides being the Body Guards of the King, this Company is the only thing now remaining in Scotland, which properly commemorates the many noble deeds performed by our ancestors by the aid of the Bow. It ought therefore to be the pride and ambition of every true Scotsman to be a member of it. Roslin’s Speech. EDINBURGH: PRINTED BY P. NEII.T.. 1819. PREFACE, T he first part of the following List, is not preserved in the handwriting of the Members themselves, and is not accurate with respect to dates; but the names are copied from the oldest Minute-books of the Company which have been preserved. The list from the 13th of May 1714, is copied from the Parchment Roll, which every Member subscribes with his own hand, in presence of the Council of the Company, when he receives his Diploma. Edinburgh, 1 5th July 1819* | f I LIST OF MEMBERS ADMITTED INTO THE ROYAL COMPANY OF SCOTTISH ARCHERS, FROM 1676, Extracted from Minute-books prior to the 13th of May 1714. -

The Excavation of Two Later Iron Age Fortified Homesteads at Aldclune

Proc Soc Antiq Scot, 127 (1997), 407-466 excavatioe Th lateo tw r f Ironfortifieo e nAg d homesteads at Aldclune, Blair Atholl, Perth & Kinross R Hingley*, H L Mooref, J E TriscottJ & G Wilsonf with contribution AshmoreJ P y sb , HEM Cool DixonD , , LehaneD MateD I , McCormickF , McCullaghJ P R , McSweenK , y &RM Spearman ABSTRACT Two small 'forts', probably large round houses, occupying naturala eminence furtherand defended by banks and ditches at Aldclune, by Blair Atholl (NGR: NN 894 642), were excavated in advance of road building. Construction began Siteat between2 second firstthe and centuries Siteat 1 BC and between the second and third centuries AD. Two major phases of occupation were found at each site. The excavation was funded by the former SDD/Historic Buildings and Monuments Directorate with subsequent post-excavation and publication work funded by Historic Scotland. INTRODUCTION In 1978 the Scottish Development Department (Ancient Monuments) instigated arrangements for excavation whe becamt ni e known tha plannee tth d re-routin trun9 A e k th roa likels f go dwa y to destroy two small 'forts' at Aldclune, by Blair Atholl (NGR: NN 894 642). A preliminary programm f triao e l trenching bega n Aprii n l 1980, revealing that substantial e areath f o s structure d theian s r defences survived e fac n th vieI . t f wo tha t both sites wer f higo e h archaeological potentia would an l almose db t completely obliterate roae th dy dbuildingb s wa t ,i decide proceeo dt d with full-scale excavation. -

The Construction of the Scottish Military Identity

RUINOUS PRIDE: THE CONSTRUCTION OF THE SCOTTISH MILITARY IDENTITY, 1745-1918 Calum Lister Matheson, B.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Geoffrey Wawro, Major Professor Guy Chet, Committee Member Michael Leggiere, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Matheson, Calum Lister. Ruinous pride: The construction of the Scottish military identity, 1745-1918. Master of Arts (History), August 2011, 120 pp., bibliography, 138 titles. Following the failed Jacobite Rebellion of 1745-46 many Highlanders fought for the British Army in the Seven Years War and American Revolutionary War. Although these soldiers were primarily motivated by economic considerations, their experiences were romanticized after Waterloo and helped to create a new, unified Scottish martial identity. This militaristic narrative, reinforced throughout the nineteenth century, explains why Scots fought and died in disproportionately large numbers during the First World War. Copyright 2011 by Calum Lister Matheson ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER I: THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH ........................................................... 1 CHAPTER II: EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: THE BUTCHER‘S BILL ................................ 10 CHAPTER III: NINETEENTH CENTURY: THE THIN RED STREAK ............................ 44 CHAPTER IV: FIRST WORLD WAR: CULLODEN ON THE SOMME .......................... 68 CHAPTER V: THE GREAT WAR AND SCOTTISH MEMORY ................................... 102 BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 112 iii CHAPTER I THE HIGHLAND WARRIOR MYTH Looking back over nearly a century, it is tempting to see the First World War as Britain‘s Armageddon. The tranquil peace of the Edwardian age was shattered as armies all over Europe marched into years of hellish destruction. -

The London Gazette, May 10, 1910. 3251

THE LONDON GAZETTE, MAY 10, 1910. 3251 At the Court at Saint James's, the 7th day of Marquess of Londonderry. May, 1910. Lord Steward. PRESENT, Earl of Derby. Earl of Pembroke and Montgomery. The KING'S Most Excellent Majesty in Council. Earl of Chesterfield. "IS Majesty being this day present in Council Earl of Kintore. was pleased to make the following' Earl of Rosebery. Declaration:— Earl Waldegrave. " My Lords and Gentlemen— Earl Carrington. My heart is too full for Me to address you Earl of Halsbury. to-day in more than a few. words. It is My Earl of Plymouth. sorrowful duty to announce to you the death of Lord Walter Gordon-Lennox. My dearly loved Father the King. In this Lord Chamberlain. irreparable loss which has so suddenly fallen Viscount Cross. upon Me and upon the whole Empire, I am Viscount Knutsford. comforted by the feeling that I have the Viscount Morley of Blackburn. sympathy of My future subjects, who will Lord Arthur Hill. mourn with Me for their beloved Sovereign, Lord Bishop of London. whose own happiness was found in sharing and Lord Denman. promoting theirs. I have lost not only a Lord Belper. Father's love, but the affectionate and intimate Lord Sandhurst. relations of a dear friend and adviser. No less Lord Revelstoke. confident am I in the universal loving sympathy Lord Ashbourne. which is assured to My dearest Mother in her Lord Macnaghten. overwhelming grief. Lord Ashcombe. Standing here a little more than nine years Lord Burghclere. ago, Our beloved King declared that as long as Lord James of Hereford. -

Highland Perthshire Through the Archive

A Guide to the History and Culture of Highland Perthshire through the Archive Dick Fotheringham, bell ringer in the Aberfeldy area, c1930s Ref: MS316/31 Perth & Kinross Council Archive 1 Foreword While I have been a member of the Friends of Perth & Kinross Council Archive for some time I only became a Committee member last year. Thus my being asked to become the chair of the Committee at this year’s AGM was, from my perspective, rather rapid promotion! Now I have been given the great honour of writing this foreword to the Friends’ latest publication, a survey and guide to sources of information on every aspect of life in Highland Perthshire as encapsulated in the collections of the Archive. In it you will find a comprehensive overview of the huge range of collections relevant to this topic including history, genealogy, industry, settlements, estates and anything else you may be interested in. Some of the material is “official”, like local authority documents, police and Justice of the Peace records. However, there is also guidance on exploring community-based collections put together by local people who were determined their “story” would live on and be accessible to anyone who was interested. There are also many illustrations of documents of different types with informative notes beside each one. These are, of course, merely a glimpse of the rich and varied sources which exist and can be explored with the help of the staff of the Archive. A feature which we hope will be seen as innovative, and was the brainchild of the authors, is a specimen analysis of a document which is designed to show you what you can learn from it whether you are a family, house or local historian, or just interested in maximising the information that a document can provide.