E:\Sociology Jrnl 08-06-18\Soci

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

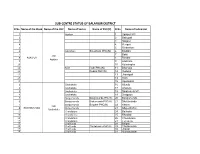

Sub-Centre Status of Balangir District

SUB-CENTRE STATUS OF BALANGIR DISTRICT Sl No. Name of the Block Name of the CHC Name of Sector Name of PHC(N) Sl No. Name of Subcenter 1 Agalpur 1 Agalpur MC 2 2 Babupali 3 3 Nagaon 4 4 Rengali 5 5 Rinbachan 6 Salebhata Salebhata PHC(N) 6 Badtika 7 7 Bakti CHC 8 AGALPUR 8 Bendra Agalpur 9 9 Salebhata 10 10 Kutasingha 11 Roth Roth PHC(N) 11 Bharsuja 12 Dudka PHC(N) 12 Duduka 13 13 Jharnipali 14 14 Roth 15 15 Uparbahal 1 Sindhekela 16 Alanda 2 Sindhekela 17 Arsatula 3 Sindhekela 18 Sindhekela MC 4 Sindhekela 19 Dedgaon 5 Bangomunda Bangomunda PHC(N) 20 Bangomunda 6 Bangomunda Bhalumunda PHC(N) 21 Bhalumunda 7 Bangomunda Belpara PHC(N) 22 Khaira CHC 8 BANGOMUNDA Bangomunda 23 Khujenbahal Sindhekela 9 Chandotora 24 Batharla 10 Chandotora 25 Bhuslad 11 Chandotora 26 Chandutara 12 Chandotora 27 Tureikela 13 Chulifunka 28 Biripali 14 Chulifunka Chuliphunka PHC(N) 29 Chuliphunka 15 Chulifunka 30 Jharial 16 Chulifunka 31 Munda padar 1 Gambhari 32 Bagdor 2 Gambhari 33 Ghagurli 3 Gambhari Gambhari OH 34 Ghambhari 4 Gambhari 35 Kandhenjhula 5 Belpada 36 Belpara MC 6 Belpada 37 Dunguripali 7 Belpada 38 Kapani 8 Belpada 39 Nunhad 9 Mandal 40 Khairmal CHC 10 BELPARA Mandal Khalipathar PHC(N) 41 Khalipatar Belpara 11 Mandal 42 Madhyapur 12 Mandal Mandal PHC(N) 43 Mandal 13 Mandal 44 Dhumabhata 14 Mandal Sulekela PHC(N) 45 Sulekela 15 Salandi 46 Bahabal 16 Salandi 47 Banmal 17 Salandi 48 Salandi 18 Salandi 49 Sarmuhan 19 Salandi 50 Kanut 1 Chudapali 51 Barapudugia 2 Chudapali Bhundimuhan PHC(N) 52 Bhundimuhan 3 Chudapali 53 Chudapali MC 4 Chudapali 54 -

Title of the Project:” Risk Reduction and Livelihood Promotion in Western Orissa”: a Consortium Initiative

Title of the Project:” Risk Reduction and Livelihood Promotion in Western Orissa”: A Consortium Initiative estern Orissa is the home to W situation of more chronically food insecurity than any other region in the state of Orissa. Visiting of droughts and flash floods are recurrent and common phenomena in Western Orissa. It is estimated that around two- third of the total population in this region face the problems of food insecurity for around nine months, as a result migration to towns and cities in search of livelihood is rampant. During the current decade in the year 2002 this area visited severe drought making the situation of people vulnerable. 81° 82° 83° 84° 85° 86° 87° 88° N ORISSA JHARKHAND W E District Wise Rain Fall Trend S DROUGHT HISTORY In Western Orissa WEST BENGAL July - 2002 22° 22° Sundargarh 1950-60 Twice Jharsuguda Mayurbhanj Keonjhar Deogarh 1960-70 Twice Balasore Baragarh Sambalpur CHHATISH GARH 21° 21° Bhadrak 1970-80 Five times Sonepur Angul Dhenkanal Jajpur Boudh Kendrapara Cuttack 1980-90 Six times Bolangir Jagatsinghpur Nuapada Khurda Nayagarh 20° 1990-2001 Thrice 20° Phulbani Puri l a g Kalahandi n 2002-2003 Statewide e Ganjam B Nawarangpur Rayagada 19° f o Drought 19° Gajapati Koraput y Reference a Rain Fall ANDHRA PRADESH Rain Fall Normal B Scanty (-60% and above) Malkangiri Rain Fall Actual Highly Deficient (-40% to -59%) National Boundary 18° 18° Deficient (-20% to -39% ) State Boundary Normal (+19% to -19%) District Boundary Composed and Printed at SPARC Pvt. ltd., Bhubaneswar Continuous erratic rainfall, undulated terrain, 81° 82° 83° 84° 85° 86° 87° 88° fragmented ecology followed by frequent droughts has severely affected the economic condition of the poor in Orissa, especially in the districts of Western Orissa since last few decades. -

View Entire Book

Orissa Review * April-May - 2009 Integration of Princely States Under Dr. Harekrushna Mahtab Balabhadra Ghadai The Constitution of Orissa Order-1936 got the different parts of the Princely States in Orissa. In approval of the British king on 3rd March, 1936. 1938 Praja Mandals (People's Association) were It was announced that the new province would formed and under their banner, struggle began come into being on 1st April, 1936 with Sir John for securing democratic rights. In the Princely State Austin Hubback, I.C.S. as the Governor. On the of Talcher a movement against feudal exploitation appointed day in a solemn ceremony held at the made significant advance. There was unrest at Ravenshaw College Hall, Cuttack, Sir John Austin Dhenkanal also where the Ruler tried his best to Hubback was administered the oath of office by suppress it. In October 1938, six persons including Sir Courtney Terrel, the Chief Justice of Bihar a 12 year old boy named Baji Rout died as a and Orissa High Court. The Governor read out result of firing. In Ranpur there was an out-break the message of goodwill received from the king- of lawlessness and the situation became serious emperor George VI and the Viceroy of India in January 1939 when the Political Agent Major Lord Linlithgow, for the people of Orissa. Thus, R.L. Bazelgatte was messacred by the mob on 5 the long cherished dream of the Oriya speaking January, 1939 at Ranpur. The troops were sent people of years at last became a reality. to crush the people's movement. -

2001 Presented Below Is an Alphabetical Abstract of Languages A

Hindi Version Home | Login | Tender | Sitemap | Contact Us Search this Quick ABOUT US Site Links Hindi Version Home | Login | Tender | Sitemap | Contact Us Search this Quick ABOUT US Site Links Census 2001 STATEMENT 1 ABSTRACT OF SPEAKERS' STRENGTH OF LANGUAGES AND MOTHER TONGUES - 2001 Presented below is an alphabetical abstract of languages and the mother tongues with speakers' strength of 10,000 and above at the all India level, grouped under each language. There are a total of 122 languages and 234 mother tongues. The 22 languages PART A - Languages specified in the Eighth Schedule (Scheduled Languages) Name of language and Number of persons who returned the Name of language and Number of persons who returned the mother tongue(s) language (and the mother tongues mother tongue(s) language (and the mother tongues grouped under each grouped under each) as their mother grouped under each grouped under each) as their mother language tongue language tongue 1 2 1 2 1 ASSAMESE 13,168,484 13 Dhundhari 1,871,130 1 Assamese 12,778,735 14 Garhwali 2,267,314 Others 389,749 15 Gojri 762,332 16 Harauti 2,462,867 2 BENGALI 83,369,769 17 Haryanvi 7,997,192 1 Bengali 82,462,437 18 Hindi 257,919,635 2 Chakma 176,458 19 Jaunsari 114,733 3 Haijong/Hajong 63,188 20 Kangri 1,122,843 4 Rajbangsi 82,570 21 Khairari 11,937 Others 585,116 22 Khari Boli 47,730 23 Khortha/ Khotta 4,725,927 3 BODO 1,350,478 24 Kulvi 170,770 1 Bodo/Boro 1,330,775 25 Kumauni 2,003,783 Others 19,703 26 Kurmali Thar 425,920 27 Labani 22,162 4 DOGRI 2,282,589 28 Lamani/ Lambadi 2,707,562 -

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA

Signatory ID Name CIN Company Name 02700003 RAM TIKA U55101DL1998PTC094457 RVS HOTELS AND RESORTS 02700032 BANSAL SHYAM SUNDER U70102AP2005PTC047718 SHREEMUKH PROPERTIES PRIVATE 02700065 CHHIBA SAVITA U01100MH2004PTC150274 DEJA VU FARMS PRIVATE LIMITED 02700070 PARATE VIJAYKUMAR U45200MH1993PTC072352 PARATE DEVELOPERS P LTD 02700076 BHARATI GHOSH U85110WB2007PTC118976 ACCURATE MEDICARE & 02700087 JAIN MANISH RAJMAL U45202MH1950PTC008342 LEO ESTATES PRIVATE LIMITED 02700109 NATESAN RAMACHANDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700110 JEGADEESAN MAHENDRAN U51505TN2002PTC049271 RESHMA ELECTRIC PRIVATE 02700126 GUPTA JAGDISH PRASAD U74210MP2003PTC015880 GOPAL SEVA PRIVATE LIMITED 02700155 KRISHNAKUMARAN NAIR U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700157 DHIREN OZA VASANTLAL U45201GJ1994PTC021976 SHARVIL HOUSING PVT LTD 02700183 GUPTA KEDAR NATH U72200AP2004PTC044434 TRAVASH SOFTWARE SOLUTIONS 02700187 KUMARASWAMY KUNIGAL U93090KA2006PLC039899 EMERALD AIRLINES LIMITED 02700216 JAIN MANOJ U15400MP2007PTC020151 CHAMBAL VALLEY AGRO 02700222 BHAIYA SHARAD U45402TN1996PTC036292 NORTHERN TANCHEM PRIVATE 02700226 HENDIN URI ZIPORI U55101HP2008PTC030910 INNER WELLSPRING HOSPITALITY 02700266 KUMARI POLURU VIJAYA U60221PY2001PLC001594 REGENCY TRANSPORT CARRIERS 02700285 DEVADASON NALLATHAMPI U72200TN2006PTC059044 ZENTERE SOLUTIONS PRIVATE 02700322 GOPAL KAKA RAM U01400UP2007PTC033194 KESHRI AGRI GENETICS PRIVATE 02700342 ASHISH OBERAI U74120DL2008PTC184837 ASTHA LAND SCAPE PRIVATE 02700354 MADHUSUDHANA REDDY U70200KA2005PTC036400 -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

Translation Strategies of the Non-Native Odia Translators (1807-1874)

Translation Strategies of the Non-Native Odia Translators (1807-1874) RAMESH C MALIK Translation strategy means a plan or procedure adopted by the translators to solve the translation problems. The present paper is to highlight on the translation strategies of the non-native Odia translators during the colonial period (1807-1874). First of all, those translators who were non-residents of Odisha and had learnt Odia for specific purposes are considered non-native Odia translators.The first name one of the Odia translators is William Carey (1761-1834), who translated the New Testament or Bible from English to Odia that was subsequently published by the Serampore Mission Press Calcutta in 1807. A master craftsman of Christian theology and an Odia translator of missionary literature, Amos Sutton (1798-1854), who translated John Bunyan’s (1628-1688) the Pilgrim’s Progress (1678) to Odia under the titled swargiya jātrira brutānta in 1838. Sutton served as an Odia translator under the British government. His religious, literary, and linguistic contributions to Odia language and literature are to be studied for making a concrete idea about the development of Odia prose. In the era of Odia translation discourse, his translations deserve to be studied in the theoretical frame of translation strategies. In this paper, the following translation strategies like linguistic strategies, literal translation strategy, lexical alteration strategy, deletion, exoticism and cultural transposition strategies are predominately adopted by the translators. Since the objectives of the SLTs were to promote religious evangelization and second language learning, the translation strategies tried to preserve the religious and pedagogical fidelity rather that textual fidelity in the translated texts. -

List of Colleges Affiliated to Sambalpur University

List of Colleges affiliated to Sambalpur University Sl. No. Name, address & Contact Year Status Gen / Present 2f or Exam Stream with Sanctioned strength No. of the college of Govt/ Profes Status of 12b Code (subject to change: to be verified from the Estt. Pvt. ? sional Affilia- college office/website) Aided P G ! tion Non- WC ! (P/T) aided Arts Sc. Com. Others (Prof) Total 1. +3 Degree College, 1996 Pvt. Gen Perma - - 139 96 - - - 96 Karlapada, Kalahandi, (96- Non- nent 9937526567, 9777224521 97) aided (P) 2. +3 Women’s College, 1995 Pvt. Gen P - 130 128 - 64 - 192 Kantabanji, Bolangir, Non- W 9437243067, 9556159589 aided 3. +3 Degree College, 1990 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 055 128 - - - 128 Sinapali, Nuapada aided (03-04) 9778697083,6671-235601 4. +3 Degree College, Tora, 1995 Pvt. Gen P-2005 - 159 128 - - - 128 Dist. Bargarh, Non- 9238773781, 9178005393 Aided 5. Area Education Society 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2002 12b 066 64 - - - 64 (AES) College, Tarbha, Aided Subarnapur, 06654- 296902, 9437020830 6. Asian Workers’ 1984 Pvt. Prof P 12b - - - 64 PGDIRPM 136 Development Institute, Aided 48 B.Lib.Sc. Rourkela, Sundargarh 24 DEEM 06612640116, 9238345527 www.awdibmt.net , [email protected] 7. Agalpur Panchayat Samiti 1989 Pvt. Gen P- 2003 12b 003 128 64 - - 192 College, Roth, Bolangir Aided 06653-278241,9938322893 www.apscollege.net 8. Agalpur Science College, 2001 Pvt. Tempo - - 160 64 - - - 64 Agalpur, Bolangir Aided rary (T) 9437759791, 9. Anchal College, 1965 Pvt. Gen P 12 b 001 192 128 24 - 344 Padampur, Bargarh Aided 6683-223424, 0437403294 10. Anchalik Kishan College, 1983 Pvt. -

Odisha As a Multicultural State: from Multiculturalism to Politics of Sub-Regionalism

Afro Asian Journal of Social Sciences Volume VII, No II. Quarter II 2016 ISSN: 2229 – 5313 ODISHA AS A MULTICULTURAL STATE: FROM MULTICULTURALISM TO POLITICS OF SUB-REGIONALISM Artatrana Gochhayat Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Sree Chaitanya College, Habra, under West Bengal State University, Barasat, West Bengal, India ABSTRACT The state of Odisha has been shaped by a unique geography, different cultural patterns from neighboring states, and a predominant Jagannath culture along with a number of castes, tribes, religions, languages and regional disparity which shows the multicultural nature of the state. But the regional disparities in terms of economic and political development pose a grave challenge to the state politics in Odisha. Thus, multiculturalism in Odisha can be defined as the territorial division of the state into different sub-regions and in terms of regionalism and sub- regional identity. The paper attempts to assess Odisha as a multicultural state by highlighting its cultural diversity and tries to establish the idea that multiculturalism is manifested in sub- regionalism. Bringing out the major areas of sub-regional disparity that lead to secessionist movement and the response of state government to it, the paper concludes with some suggestive measures. INTRODUCTION The concept of multiculturalism has attracted immense attention of the academicians as well as researchers in present times for the fact that it not only involves the question of citizenship, justice, recognition, identities and group differentiated rights of cultural disadvantaged minorities, it also offers solutions to the challenges arising from the diverse cultural groups. It endorses the idea of difference and heterogeneity which is manifested in the cultural diversity. -

GIPE-017791-Contents.Pdf (2.126Mb)

OFFICIAL AG~NTS . FOR THE SALE OF GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. In India. MESSRS. THA.CXBK, SPINK & Co., Calcutta and Simla. · MESSRS. NEWKA.N & Co., Calcutta. MESSRS. HIGGINBOTHA.M & Co., Madras. MESSRS. THA.Ci:BB & Co., Ln., Bombay. MESSRS . .A.. J. CoHBRIDGB & Co., Bombay. THE SUPERINTENDENT, .A.M:ERICA.N BA.l'TIS'l MISSION PRESS, Ran~toon. Mas. R.l.DHA.BA.I ATKARA.M SA.aooN, Bombay. llissas. R. CA.HBRA.Y & Co., Calcutta. Ru SA.HIB M. GuL&B SINGH & SoNs, Proprietors of the Mufid.i-am Press, Lahore, Punjab. MEsSRS. THoMPSON & Co., Madras. MESSRS. S. MuRTHY & Co., Madras. MESSRS. GoPA.L NA.RA.YEN & Co., Bombay. AhssRs. B. BuiERlEB & Co., 25 Cornwallis Street,· Calcutta. MBssas. S. K. LA.HlRI & Co., Printers and Booksellers, College Street, Calcutta. MESSRS. V. KA.LYA.NA.RUIA. IYER & Co., Booksellers, &c., Madras. MESSRS. D. B. TA.RA.POREVA.LA., SoNs & Co., Booksellers, Bombay. MESSRS. G. A; NA.TESON & Co., Madras. MR. N. B. MA.THUR, Superintendent, Nazair Kanum Hind Press, AJlahabad. - TnB CA.LCUTTA. ScHOOL Boox SociETY. MR. SUNDER PA.NDURA.NG, Bombay. MESSRs. A.M. A.ND J. FERGusoN, Ceylon. MEssRsrTEMPI.B & Co., Madras. · MEssRs. CoHBRIDGB & Co., Madras •. MESSRS. A. R. PILLA.I & Co., Trivandrum. ~bssRs. A. CHA.ND &-Co., Lahore, Punjab. ·- .·· BA.Bu S. C. T.A.LUXDA.B, Proprietor, Students & Co., Ooocli Behar. ------' In $ng~a»a.~ AIR. E. A. • .ARNOLD, 41 & 43 -M.ddo:x:• Street, Bond Street, London, W. , .. MESSRS. CoNSTA.BLB & Co., 10 Orange· Sheet, Leicester Square, London, W. C. , MEssRs. GaiNDLA.Y & Co., 64. Parliament Street, London, S. -

View Entire Book

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXX NO. 8 MARCH - 2014 PRADEEP KUMAR JENA, I.A.S. Principal Secretary PRAMOD KUMAR DAS, O.A.S.(SAG) Director DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Sri Krsna - Jagannath Consciousness : Vyasa - Jayadeva - Sarala Dasa Dr. Satyabrata Das ... 1 Good Governance ... 3 Classical Language : Odia Subrat Kumar Prusty ... 4 Language and Language Policy in India Prof. Surya Narayan Misra ... 14 Rise of the Odia Novel : 1897-1930 Jitendra Narayan Patnaik ... 18 Gangadhar Literature : A Bird’s Eye View Jagabandhu Panda ... 23 Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty Dr. Sarat Chandra Rath ... 25 The Evolution of Odia Language : An Introspection Dr. Jyotirmati Samantaray ... 29 Biju - The Greatest Odia in Living Memory Rajkishore Mishra ... 31 Binode Kanungo (1912-1990) - A Versatile Genius ... 34 Role of Maharaja Sriram Chandra Bhanj Deo in the Odia Language Movement Harapriya Das Swain ... 38 Odissi Vocal : A Unique Classical School Kirtan Narayan Parhi .. -

Mapping India's Language and Mother Tongue Diversity and Its

Mapping India’s Language and Mother Tongue Diversity and its Exclusion in the Indian Census Dr. Shivakumar Jolad1 and Aayush Agarwal2 1FLAME University, Lavale, Pune, India 2Centre for Social and Behavioural Change, Ashoka University, New Delhi, India Abstract In this article, we critique the process of linguistic data enumeration and classification by the Census of India. We map out inclusion and exclusion under Scheduled and non-Scheduled languages and their mother tongues and their representation in state bureaucracies, the judiciary, and education. We highlight that Census classification leads to delegitimization of ‘mother tongues’ that deserve the status of language and official recognition by the state. We argue that the blanket exclusion of languages and mother tongues based on numerical thresholds disregards the languages of about 18.7 million speakers in India. We compute and map the Linguistic Diversity Index of India at the national and state levels and show that the exclusion of mother tongues undermines the linguistic diversity of states. We show that the Hindi belt shows the maximum divergence in Language and Mother Tongue Diversity. We stress the need for India to officially acknowledge the linguistic diversity of states and make the Census classification and enumeration to reflect the true Linguistic diversity. Introduction India and the Indian subcontinent have long been known for their rich diversity in languages and cultures which had baffled travelers, invaders, and colonizers. Amir Khusru, Sufi poet and scholar of the 13th century, wrote about the diversity of languages in Northern India from Sindhi, Punjabi, and Gujarati to Telugu and Bengali (Grierson, 1903-27, vol.