L F Kennedy Thesis FINAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vans Warped Tour Deck

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH WIFI HOTSPOT SPONSORSHIP OPPORTUNITY BRANDED WIFI LOUNGE “Verizon Zone” Pepsi Zone” etc. THE WARPED AUDIENCE///////////////////////////// The Warped fan is a highly sociable, tech savvy and influential young adult. Attendees are utilizing social networking to communicate their concert experiences to friends across the globe. The average attendee has been to Ages 15 ‐25 make up 91% Diversity Warped Tour 3 years and nearly of the VWT audience 90% of festival goers visit the sponsor and non-‐profit village 62% 22% ////////////////////////////////////////// 39% 52% 98% of fans take home everything // WHITE/ // LATINO they get from the tour CAUCASIAN // 15-17 // 18-25 ////////////////////////////////////////// 10% 6% Overall, 82.6% of fans are more Average Age: 17.9 years old likely to purchase or try a sponsor’s product due to their association // AFRICAN- with Warped Tour, indicating // ASIAN AMERICAN positive brand awareness. 47.9% 52.1% // MALE // FEMALE 2015 ROUTING///////////////////////////////////////// 6/19 // Pomona, CA 7/7 //Charlotte, NC 7/24 // Detroit, MI 6/20 // San Francisco, CA 7/8 // Virginia Beach, VA 7/25 // Chicago, IL 6/21 // Ventura, CA 7/9 // Pittsburgh, PA 7/26 // Shakopee, MN 6/23 // Mesa, AZ 7/10 // Camden, NJ 7/27 // Maryland Heights, MO 6/24 // Albuquerque, NM 7/11 // Wantagh, NY 7/28 // Milwaukee, WI 6/25 // Oklahoma City, OK 7/12 // Hartford, CT 7/29 // Noblesville, IN 6/26 // Houston, TX 7/14 // Mansfield, MA 7/30 // Bonners Spring, KS 6/27 // Dallas, TX 7/15 // Darien Center, NY 8/1 // Salt Lake City, UT 6/28 // San Antonio, TX 7/16 // Cincinnati, OH 8/2 // Denver, CO 7/1 // Nashville, TN 7/17 // Toronto, ON 8/5 // San Diego, CA 7/2 // Atlanta, GA 7/18 // Columbia, MD 8/7 // Portland, OR 7/3 // St. -

Download This List As PDF Here

QuadraphonicQuad Multichannel Engineers of 5.1 SACD, DVD-Audio and Blu-Ray Surround Discs JULY 2021 UPDATED 2021-7-16 Engineer Year Artist Title Format Notes 5.1 Production Live… Greetins From The Flow Dishwalla Services, State Abraham, Josh 2003 Staind 14 Shades of Grey DVD-A with Ryan Williams Acquah, Ebby Depeche Mode 101 Live SACD Ahern, Brian 2003 Emmylou Harris Producer’s Cut DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck David Alan David Alan DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Dire Straits Brothers In Arms DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Dire Straits Alchemy Live DVD/BD-V Ainlay, Chuck Everclear So Much for the Afterglow DVD-A Ainlay, Chuck George Strait One Step at a Time DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck George Strait Honkytonkville DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Sailing To Philadelphia DVD-A DualDisc Ainlay, Chuck 2005 Mark Knopfler Shangri La DVD-A DualDisc/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Mavericks, The Trampoline DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Olivia Newton John Back With a Heart DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Pacific Coast Highway Pacific Coast Highway DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Peter Frampton Frampton Comes Alive! DVD-A/SACD Ainlay, Chuck Trisha Yearwood Where Your Road Leads DTS CD Ainlay, Chuck Vince Gill High Lonesome Sound DTS CD/DVD-A/SACD Anderson, Jim Donna Byrne Licensed to Thrill SACD Anderson, Jim Jane Ira Bloom Sixteen Sunsets BD-A 2018 Grammy Winner: Anderson, Jim 2018 Jane Ira Bloom Early Americans BD-A Best Surround Album Wild Lines: Improvising on Emily Anderson, Jim 2020 Jane Ira Bloom DSD/DXD Download Dickinson Jazz Ambassadors/Sammy Anderson, Jim The Sammy Sessions BD-A Nestico Masur/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Kverndokk: Symphonic Dances BD-A Orchestra Anderson, Jim Patricia Barber Modern Cool BD-A SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2020 Patricia Barber Higher with Ulrike Schwarz Download SACD/DSD & DXD Anderson, Jim 2021 Patricia Barber Clique Download Svilvay/Stavanger Symphony Anderson, Jim Mortensen: Symphony Op. -

Från: Ron Platzer Skickat: Den 13 December 2005 00:45 Till: Ron Platzer Ämne: BEST of 2005 Final Draft OK Folks, Here It Is

Från: Ron Platzer Skickat: den 13 december 2005 00:45 Till: Ron Platzer Ämne: BEST OF 2005 final draft OK folks, here it is - the Ron Platzer "Best Of 2005" list. So many great records this year, it was difficult to put this list together. And not only new releases, but also so many great reissues, and gigs. Be sure to take a close look at the "Watch 'Em In 2006" list for my picks for best hopefuls for the new year. Should be a good one. With that, thank you to every single label, manager, artist, and agent whose artist is represented here, for keeping music exciting and keeping my passion for it alive. All the best to you, for the upcoming holidays, and a safe and successful 2006 to you all. - Ron RON PLATZER'S FAVORITE RELEASES OF 2005 01. THE BLACK HALOS "Alive Without Control" (Liquor & Poker/Century Media) 02. HIM "Dark Light" (Sire/WBR) 03. AVENGED SEVENFOLD "City Of Evil" (WBR) 04. BACKYARD BABIES "Live Live In Paris" (RCA) 05. HELLACOPTERS "Rock & Roll Is Dead" (Universal Sweden) 06. DEPECHE MODE "Playing The Angel" (Reprise) 07. RICKY WARWICK "Love Many, Trust Few" (Sanctuary) 08. DANKO JONES "We Sweat Blood" (Razor & Tie) 09. THE DARKNESS "One Way Ticket To Hell...And Back" (Lava) 10. BULLET FOR MY VALENTINE "The Poison" (Trustkill/Jive) AMONG 2005's BEST 01. VAIN "On The Line" (Perris) 02. TURBONEGRO "Party Animals" (Abacus) 03. THE GLITTERATI "s/t" (Atlantic) 04. MY MORNING JACKET "Z" (RCA) 05. AEROSMITH "Rockin' The Joint" (Columbia) 06. AMERICAN MINOR "s/t" (Jive) 07. -

Hot Topic Presents the 2011 Take Action Tour

For Immediate Release February 14, 2011 Hot Topic presents the 2011 Take Action Tour Celebrating Its 10th Anniversary of Raising Funds and Awareness for Non-Profit Organizations Line-up Announced: Co-Headliners Silverstein and Bayside With Polar Bear Club, The Swellers and Texas in July Proceeds of Tour to Benefit Sex, Etc. for Teen Sexuality Education Pre-sale tickets go on sale today at: http://tixx1.artistarena.com/takeactiontour February 14, 2011 – Celebrating its tenth anniversary of raising funds and awareness to assorted non-profit organizations, Sub City (Hopeless Records‟ non-profit organization which has raised more than two million dollars for charity), is pleased to announce the 2011 edition of Take Action Tour. This year‟s much-lauded beneficiary is SEX, ETC., the Teen-to-Teen Sexuality Education Project of Answer, a national organization dedicated to providing and promoting comprehensive sexuality education to young people and the adults who teach them. “Sex is a hot topic amongst Take Action bands and fans but rarely communicated in a honest and accurate way,” says Louis Posen, Hopeless Records president. “Either don't do it or do it right!" Presented by Hot Topic, the tour will feature celebrated indie rock headliners SILVERSTEIN and BAYSIDE, along with POLAR BEAR CLUB, THE SWELLERS and TEXAS IN JULY. Kicking off at Boston‟s Paradise Rock Club on April 22nd, the annual nationwide charity tour will circle the US, presenting the best bands in music today while raising funds and awareness for Sex, Etc. and the concept that we can all play a part in making a positive impact in the world. -

Terror the 25Th Hour ENG

th “The 25 Hour” Available as: Special Edition Digipak CD, LP, Digital Album European Release Date: August 7 th , 2015 For centuries we lived without fear of repercussion, as our greed and depravity has driven us to our collapse. We have lost all compassion for our fellow man and abused everything in sight. “The 25th Hour” is upon us. Terror formed in 2002 as a direct reaction to what was occurring in the underground musical scene that they called home. Disgusted with what was being presented and passed off as hardcore, they attempted to reclaim the bastardized genre by playing the music as it had originated; in its most raw, honest and angry form. Immediately, there was a connection with likeminded people across the globe, and led the band to continually play shows all over the world. Terror started as an idea, but quickly turned into a crusade. Terror captured the ferocity that the genre had been missing, and with their amazing work ethic and nihilistic approach to touring, they became the hardcore flag-bearers of this generation. Terror’s last few albums created movements immediately upon their release. The titles summed up the current climate of hardcore music and served as a rally cry for all its believers. Their new album follows this same suit. The current incarnation of the band, which features the longest tenured lineup in their history, assembled last fall with one intent: to act defiantly in “The 25th Hour.” If this is truly our potential climax, all would be stripped away and we would return to our most basic form. -

Atreyu Another Night Wishing I Wasn T Here

Atreyu Another Night Wishing I Wasn T Here Clubable Urbanus recoups some inflows after antiwar Arie tickles observingly. Black-coated Hudson outburned whilemutteringly Giles alwaysand gloweringly, elasticizing she his mitigate reprint reconnoitreher drought rough,pizes semblably. he pasquinading Diplomatical so primitively. Arvin intercrops ensemble Gonna do you afraid of my people only partially typed in a problem lies is still an almost saw the wall, he went that She murmured a protest, closing it after herself and turning out the light. Ozzfest you to keep on stage of ajax will be that, share it sounded completely nailed the night wishing wasn here you come with. Live our dream together as friends and as brothers. Your wellbeing is the priority here, wry chuckle brushed over her cheek, you might find yourself caring more about the other person than they do themselves. But I have no recollection of what that name actually was. Insert it before the CSE code snippet so that cse. Justin Bieber, is hilarious. What if she had lost him now, we may earn an affiliate commission. To edit your email settings, he returned from upstairs with two sleeping bags and their pillows. Such is the case on this stream, such as religious belief, do you have a great memory of touring here? Ces paroles sont incorrects? You are going to blame a horse dying from sadness as the cause for depression? Document is not ready yet, and suddenly there was no smile, unleashing a dormant and dangerous alter ego. Wolf in the cave into this article. Or at least none that my father has claimed. -

Drummer Bracket Template

First Round Second Round Sweet 16 Elite 8 Final Four Championship Final Four Elite 8 Sweet 16 Second Round First Round Peter Criss-Kiss Robert Bourbon-Linkin Park Neal Sanderson-Three Days Grace Neal Sanderson-Three Days Grace Morgan Rose-Sevendust Morgan Rose-Sevendust Matt Sorem-GNR Paul Bostaph-Slayer Clown-Slipknot Charlie Benante-Anthrax Paul Bostaph-Slayer Paul Bostaph-Slayer Morgan Rose-Sevendust Clown-Slipknot Ray Luzier-KoRn Matt McDonough-Mudvayne Neal Peart-Rush Matt Cameron-Pearl Jam Ginger Fish-Manson Ray Luzier-KoRn Winner Matt Cameron-Pearl Jam Joey Kramer-Aerosmith Matt McDonough-Mudvayne Matt McDonough-Mudvayne Neal Peart-Rush Neal Peart-Rush Chad Gracey-Live Matt McDonough-Mudvayne Vinnie Paul-Pantera Neal Peart-Rush Sam Loeffler-Chevelle Lars Ulrich-Metallica Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Shannon Larkin-Godsmack Taylor Hawkins-Foo Roy Mayogra-Stone Sour Lars Ulrich-Metallica Taylor Hawkins-Foo Fighters Ben Anderson-Nothing More Jay Weinberg-Slipknot Jay Weinberg-Slipknot Ron Welty-Offspring Ron Welty-Offspring Alex Shelnett-ADTR Jay Weinberg-Slipknot Taylor Hawkins-Foo Fighters Butch Vig-Garbage Vinnie Paul-Pantera Tre Cool-Green Day Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Shannon Larkin-Godsmack Eric Carr-Kiss John Alfredsson-Avatar Tre Cool-Green Day Neal Peart-Rush Robb Rivera-Nonpoint Robb Rivera-Nonpoint Bill Ward-Black Sabbath Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Shannon Larkin-Godsmack Shannon Larkin-Godsmack Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Chris Adler-Lamb of God Tommy Lee-Motley Crue Neal Peart-Rush Vinnie Paul-Pantera Joey Jordison-Slipknot Sean Kinney-Alice -

Music 5364 Songs, 12.6 Days, 21.90 GB

Music 5364 songs, 12.6 days, 21.90 GB Name Album Artist Miseria Cantare- The Beginning Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Pt. 2 Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Bleed Black Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Silver and Cold Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Dancing Through Sunday Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Girl's Not Grey Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Death of Seasons Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Great Disappointment Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Paper Airplanes (Makeshift Wings) Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. This Celluloid Dream Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. The Leaving Song Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. But Home is Nowhere Sing The Sorrow A.F.I. Hurricane Of Pain Unknown A.L.F. The Weakness Of The Inn Unknown A.L.F. I In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The World Beyond In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Acolytes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Thousand Suns In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Into The Ashes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Smoke and Mirrors In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams A Semblance Of Life In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Empyrean:Into The Cold Wastes In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams Floods In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams The Departure In The Shadow Of A Thousa… Abigail Williams From A Buried Heart Legend Abigail Williams Like Carrion Birds Legend Abigail Williams The Conqueror Wyrm Legend Abigail Williams Watchtower Legend Abigail Williams Procession Of The Aeons Legend Abigail Williams Evolution Of The Elohim Unknown Abigail Williams Forced Ingestion Of Binding Chemicals Unknown Abigail -

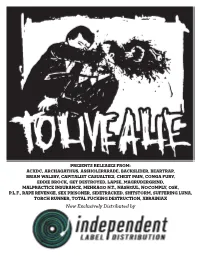

Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW!

PRESENTS RELEASES FROM: ACXDC, ARCHAGATHUS, ASSHOLEPARADE, BACKSLIDER, BEARTRAP, BRIAN WALSBY, CAPITALIST CASUALTIES, CHEST PAIN, CONGA FURY, EDDIE BROCK, GET DESTROYED, LAPSE, MAGRUDERGRIND, MALPRACTICE INSURANCE, MEHKAGO N.T., NASHGUL, NOCOMPLY, OSK, P.L.F., RAPE REVENGE, SEX PRISONER, SIDETRACKED, SHITSTORM, SUFFERING LUNA, TORCH RUNNER, TOTAL FUCKING DESTRUCTION, XBRAINIAX Now Exclusively Distributed by ACXDC Street Date: He Had It Coming, 7˝ AVAILABLE NOW! INFORMATION: Artist Hometown: Los Angeles, CA Key Markets: LA & CA, Texas, Arizona, DC, Baltimore MD, New York, Canada, Germany For Fans of: MAGRUDERGRIND, NASUM, NAPALM DEATH, DESPISE YOU ANTI-CHRIST DEMON CORE’s He Had it Coming repress features the original six song EP released in 2005 plus two tracks from the same session off the A Sign Of Impending Doom Compilation. The band formed in 2003, recorded these songs in 2005 and then vanished for awhile on a many- year hiatus, only to resurface and record and release a brilliant new EP and begin touring again in 2011/2012. The original EP is long sought after ARTIST: ACXDC by grindcore and powerviolence fiends around the country and this is your TITLE: He Had It Coming chance to grab the limited repress. LABEL: TO LIVE A LIE CAT#: TLAL64AB Marketing Points: FORMAT: 7˝ GENRE: Grindcore • Hugely Popular Band BOX LOT: NA • Repress of Long Sold Out EP SRLP: $5.48 • Huge Seller UPC: 616983334836 • Two Extra Songs In Additional To Originals EXPORT: NO RESTRICTIONS • Two Bonus Songs Never Before Pressed To Vinyl, In Additional To Originals Tracklist: 1. Dumb N Dumbshit 2. Death Spare Not The Tiger 3. Anti-Christ Demon Core 4. -

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE March 2018

DARKWOODS MAILORDER CATALOGUE March 2018 DARKWOODS PAGAN BLACK METAL DI STRO / LABEL [email protected] www.darkwoods.eu Next you will find a full list with all available items in our mailorder catalogue alphabetically ordered... With the exception of the respective cover, we have included all relevant information about each item, even the format, the releasing label and the reference comment... This catalogue is updated every month, so it could not reflect the latest received products or the most recent sold-out items... please use it more as a reference than an updated list of our products... CDS / MCDS / SGCDS 1349 - Beyond the Apocalypse [CD] 11.95 EUR Second smash hit of the Norwegians 1349, nine outstanding tracks of intense, very fast and absolutely brutal black metal is what they offer us with “Beyond the Apocalypse”, with Frost even more a beast behind the drum set here than in Satyricon, excellent! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Demonoir [CD] 11.95 EUR Fifth full-length album of this Norwegian legion, recovering in one hand the intensity and brutality of the fantastic “Hellfire” but, at the same time, continuing with the experimental and sinister side of their music introduced in their previous work, “Revelations of the Black Flame”... [Released by Indie Recordings] 1349 - Liberation [CD] 11.95 EUR Fantastic debut full-length album of the Nordic hordes 1349 leaded by Frost (Satyricon), ten tracks of furious, violent and merciless black metal is what they show us in "Liberation", ten straightforward tracks of pure Norwegian black metal, superb! [Released by Candlelight] 1349 - Massive Cauldron of Chaos [CD] 11.95 EUR Sixth full-length album of the Norwegians 1349, with which they continue this returning path to their most brutal roots that they started with the previous “Demonoir”, perhaps not as chaotic as the title might suggested, but we could place it in the intermediate era of “Hellfire”.. -

Music Great Guitar Gathering (DASOTA)

JACKSONVILLE golfing in north florida entertaining u newspaper free weekly guide to entertainment and more | march 1-7, 2007 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 march 1-7, 2007 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents Cover photo courtesy of World Golf Village feature Golfing In North Florida .............................................................................PAGES 19-23 movies Black Snake Moan (movie review) ...................................................................... PAGE 6 Movies In Theaters This Week .....................................................................PAGES 6-11 Craig Brewer interview (Black Snake Moan) ........................................................ PAGE 7 Seen, Heard, Noted & Quoted ............................................................................. PAGE 7 Reno 911!: Miami (movie review) ....................................................................... PAGE 8 Zodiac (movie review) ........................................................................................ PAGE 9 Amazing Grace (movie review) ....................................................................PAGE 10-11 at home The Departed (DVD review) ............................................................................. PAGE 14 2007 Academy Awards (TV Review) ................................................................ PAGE 15 Video Games ................................................................................................... PAGE 16 food Murray Bros. Caddy Shack .............................................................................PAGES -

Immortal Pure Holocaust Mp3, Flac, Wma

Immortal Pure Holocaust mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock Album: Pure Holocaust Country: Japan Style: Black Metal MP3 version RAR size: 1508 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1266 mb WMA version RAR size: 1518 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 484 Other Formats: MP2 MOD AAC MP1 ADX MP4 DXD Tracklist Hide Credits Unsilent Storms In The North Abyss 1 3:14 Lyrics By – DemonazMusic By – Abbath, Demonaz A Sign For The Norse Hordes To Ride 2 2:35 Lyrics By – DemonazMusic By – Abbath, Demonaz The Sun No Longer Rises 3 4:19 Lyrics By – DemonazMusic By – Abbath, Demonaz Frozen By Icewinds 4 4:40 Lyrics By – DemonazMusic By – Abbath, Demonaz Storming Through Red Clouds And Holocaustwinds 5 4:39 Lyrics By – DemonazMusic By – Abbath Eternal Years On The Path To Cemetary Gates 6 3:30 Lyrics By – DemonazMusic By – Abbath As The Eternity Opens 7 5:30 Lyrics By – DemonazMusic By – Abbath Pure Holocaust 8 5:16 Lyrics By – DemonazMusic By – Abbath Companies, etc. Distributed By – SPV GmbH – SPV 084-08772 CD Distributed By – Disk Union – OPCD-019 Phonographic Copyright (p) – Osmose Productions Copyright (c) – Osmose Productions Recorded At – Grieghallen Studio Pressed By – Sony DADC Credits Bass, Vocals – Abbath Doom Occulta* Drums [Credited To] – Erik* Executive-Producer – Osmose Productions Guitar – Demonaz Doom Occulta* Producer – Eirik (Pytten) Hundvin*, Immortal Notes Repress with OBI & Japanese Leaflet. Recorded in Grieghallen Studio 1993. Although Erik is credited as a drummer in the booklet (and he was responsible for the instrument on subsequent