Stratigraphies: a Portfolio of Intermedia Installations Exploring the Relationship of Place and Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROBERT WYATT Title: ‘68 (Cuneiform Rune 375) Format: CD / LP / DIGITAL

Bio information: ROBERT WYATT Title: ‘68 (Cuneiform Rune 375) Format: CD / LP / DIGITAL Cuneiform promotion dept: (301) 589-8894 / fax (301) 589-1819 email: joyce [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (Press & world radio); radio [-at-] cuneiformrecords.com (North American & world radio) www.cuneiformrecords.com FILE UNDER: ROCK “…the [Jim Hendrix] Experience let me know there was a spare bed in the house they were renting, and I could stay there with them– a spontaneous offer accepted with gratitude. They’d just hired it for a couple of months… …My goal was to make the music I’d actually like to listen to. … …I was clearly imagining life without a band at all, imagining a music I could make alone, like the painter I always wanted to be.” – Robert Wyatt, 2012 Some have called this - the complete set of Robert Wyatt's solo recordings made in the US in late 1968 - the ultimate Holy Grail. Half of the material here is not only previously unreleased - it had never been heard, even by the most dedicated collectors of Wyatt rarities. Until reappearing, seemingly out of nowhere, last year, the demo for “Rivmic Melodies”, an extended sequence of song fragments destined to form the first side of the second album by Soft Machine (the band Wyatt had helped form in 1966 as drummer and lead vocalist, and with whom he had recorded an as-yet unreleased debut album in New York the previous spring), was presumed lost forever. As for the shorter song discovered on the same acetate, “Chelsa”, it wasn't even known to exist! This music was conceived by Wyatt while off the road during and after Soft Machine's second tour of the US with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, first in New York City during the summer of 1968, then in the fall of that year while staying at the Experience's rented house in California, where he was granted free access to the TTG recording facility during studio downtime. -

Steve Beresford - David Toop John Zorn - Tonie Marshall

Steve Beresford - David Toop John Zorn - Tonie Marshall Deadly Weapons nato 950 Illustration : Pierre Cornuel Steve Beresford : piano - David Toop : flûte, guitare, percussions John Zorn : saxophone alto, clarinette - Tonie Marshall : voix Sortie en magasin le 10 octobre 2011 Produit par Jean Rochard pour nato Distribué par l’Autre Distribution 02.47.50.79.79 Contact presse : Christelle Raffaëlli [email protected] 06 82 65 92 73 www.natomusic.fr DEADLY WEAPONS « Ca s’appelle un disque phare ou un diamant noir » (Première) Deadly Weapons est un album clé pour les disques nato. En 1985, John Zorn joue pour la première fois en France avec Steve Beresford et David Toop au festival de Chantenay-Villedieu. Deadly Weapons, réalisé l'année d'après, est la suite naturelle de ce concert remarqué. Steve Beresford, lui, est un des piliers de la maison ; avec Deadly Weapons, il synthétise ses éclectiques et fourmillantes approches en un seul projet. David Toop a déjà enregistré pour nato avec le groupe Alterations et participé à l'album de son compère Steve Beresford : Dancing the Line Anne Marie Beretta. Tous trois sont d'incorrigibles cinéphiles. Tonie Marshall est alors actrice, et quelle actrice ! Elle va bientôt passer de l'autre côté de la caméra et devenir une cinéaste de premier plan. Deadly Weapons est un disque-film comme les affectionne particulièrement la maison du chat. Il joue sur différents plans et s'en joue. Champ et hors-champ. Lors de sa sortie, il divise : le livret rappelle comment s’offusquèrent les puristes et comment se réjouirent les autres ! Si Deadly Weapons, premier album londonien de nato, ouvre bel et bien la marche (toujours randonneuse) de ce qui va suivre, il s'inscrit assez logiquement dans ce qui a précédé en affichant des libertés nouvelles et sa passion des images sans masques. -

Ultima Oslo Contemporary Music Festival on Nature

ultima oslo contemporary 10–19 september 2015 ultima music festival oslo contemporary music festival om natur 10.–19. september 2015 10.–19. on nature 1 programme THURSDAY 10 SEPTEMBER Lunchtime concert Henrik Hellstenius Ørets teater III: Ultima Academy Cecilie Ore Ultima Academy Eivind Buene Georg Friedrich Haas In Vain SATURDAY 19 SEPTEMBER Herman Vogt Om naturen (WP) Alexander Schubert in conversation Adam & Eve—A Divine Comedy Geologist Henrik H. Svensen The Norwegian Chamber Orchestra Ensemble Ernst Ultima Remake Concordia Discors, Études (WP) Oslo Sinfonietta / Dans les Arbres with rob Young 21:00 — Kulturkirken Jakob on issues in the Age of Man 19:00 — Universitetets aula 21:00 — Riksscenen Edvin Østergaard (WP) / 10:00 — Edvard Munch Secondary 12:00 — Loftet 19:30 — The Norwegian National Opera 14:00 — Kulturhuset p. 18 19:30 — Kulturhuset New music by Eivind Buene, plus the Spellbinding piece described as ‘an optical Jan Erik Mikalsen (WP) / Maja Linderoth School Piano studies with Ian Pace, piano & Ballet, (Also 12 and 13 September) p. 31 p. 35 pieces that inspired it illusion for the ear’” The Norwegian Soloists’ Choir Interactive installation created by pupils p. 19 Concert / performance Robert Ashley Perfect Lives p. 38 p. 47 13:00 — Universitetets gamle festsal p. 13 p. 16 Ultima Academy Matmos Ultima Academy p. 53 Installation opening and concert Music Professor Rolf Inge Godøy 22:00 — Vulkan Arena Musicologist Richard Taruskin on David Toop Of Leonardo da Vinci — James Hoff / Afrikan Sciences / Ultima Academy Elin Mar Øyen Vister Røster III (WP) Installation opening on sound and gesture American electronica duo perform cele- birdsong, music and the supernatural Quills / a Black Giant / Deluge (WP) Hilde Holsen Øyvind Torvund (WP) / Jon Øivind Media theorist Wolfgang Ernst 15:00 — Deichmanske Ali Paranadian Untitled I, 14:30 — Kulturhuset brated TV opera 20:30 — Kulturhuset Elaine Mitchener / David Toop 22:00 — Blå Ness (WP) / Iannis Xenakis on online culture and hovedbibliotek A Poem for Norway (WP) p. -

A History of Sound Art Arranged and Composed by J Milo Taylor Mixed by Joel Cahen

A History of Sound Art Arranged and Composed by J Milo Taylor Mixed by Joel Cahen A History of Sound Art - A5 24pp symbols.indd 1 24/1/11 14.35.28 » Sleep Research Facility d-deck » A Hackney Balcony » Cathy Lane » Ros Bandt 00:00 01:00 02:00 03:00 Introduction » Charlie Fox » Janet Cardiff » John Cage A History of Sound Art I listen, I hear, I obey. Does the exquisitely dissonant institution of Sound Art, and its subsequent ordering of desire, ensure that we subscribe to a genealogy I hear silence, an absent sense of through which it is governed? knowing, of the heard, that I project into In this composition I hear a rhizomic a future. As a listener at the end of this collective, which obeys, albeit work I feel like a wobbly toddler looking contradictorily, a government in the mirror and happily hallucinating in of past and future time. my own disunity. I am left with the idea ‘Tomtoumtomtoumtomtoum’; the ‘Cage’ of an uncomfortable wholeness. The of Sound Art’s past. I hear hindsight. reconciliation of sonic arts past with its ‘Bwwaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa’; the future seems like an empirical illusion. sound of sonic arts future. Ennioa Neoptolomus A History of Sound Art - A5 24pp symbols.indd 2 24/1/11 14.35.29 » Brandon LaBelle » Marcel Duchamp Interview 02:00 03:00 04:00 05:00 06:00 Early Practices Dada » Enrico Caruso o sole mio » Janet Cardiff » Hugo Ball Karawane (1916) » Thomas Alva Edison Dickson Sound Film (1897) CATHY LANE Composer and sound designer. -

David Toop Ricocheting As a 1960S Teenager Between Blues Guitarist

David Toop Ricocheting as a 1960s teenager between blues guitarist, art school dropout, Super 8 film loops and psychedelic light shows, David Toop has been developing a practice that crosses boundaries of sound, listening, music and materials since 1970. This practice encompasses improvised music performance (using hybrid assemblages of electric guitars, aerophones, bone conduction, lo-fi archival recordings, paper, sound masking, water, autonomous and vibrant objects), writing, electronic sound, field recording, exhibition curating, sound art installations and opera (Star-shaped Biscuit, performed in 2012). It includes seven acclaimed books, including Rap Attack (1984), Ocean of Sound (1995), Sinister Resonance (2010) and Into the Maelstrom (2016), the latter a Guardian music book of the year, shortlisted for the Penderyn Music Book Prize. Briefly a member of David Cunningham’s pop project The Flying Lizards (his guitar can be heard sampled on “Water” by The Roots), he has released thirteen solo albums, from New and Rediscovered Musical Instruments on Brian Eno’s Obscure label (1975) and Sound Body on David Sylvian’s Samadhisound label (2006) to Entities Inertias Faint Beings on Lawrence English’s ROOM40 (2016). His 1978 Amazonas recordings of Yanomami shamanism and ritual - released on Sub Rosa as Lost Shadows (2016) - were called by The Wire a “tsunami of weirdness” while Entities Inertias Faint Beings was described in Pitchfork as “an album about using sound to find one’s own bearings . again and again, understated wisps of melody, harmony, and rhythm surface briefly and disappear just as quickly, sending out ripples that supercharge every corner of this lovely, engrossing album.” In the early 1970s he performed with sound poet Bob Cobbing, butoh dancer Mitsutaka Ishii and drummer Paul Burwell, along with key figures in improvisation, including Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Georgie Born, Hugh Davies, John Stevens, Lol Coxhill, Frank Perry and John Zorn. -

Bloomsbury MUSIC Cat.Indd

MUSIC & SOUND STUDIES 2013-14 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS 33 1/3 is a series of short books about popular music, focusing on individual albums by a variety of artists. Launched in 2003, the series will publish its 100th book in 2014 and has been widely acclaimed and loved by fans, musicians and scholars alike. LAUNCHING SPRING 2014 new in 2013 new in 2013 new in 2014 9781623562878 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623569150 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623567149 $14.95 | £8.99 new in 2014 new in 2014 new in 2014 Bloomsbury Collections delivers instant access to quality research and provides libraries with a exible way to build ebook collections. 9781623568900 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623560652 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623562588 $14.95 | £8.99 Including ,+ titles in subject areas across the humanities and social sciences, the platform features content from Bloomsbury’s latest research publications as well as a + year legacy including Continuum, Berg, Bristol Classical Press, T&T Clark and The Arden Shakespeare. ■ Music & Sound Studies collection ■ Search full text of titles; browse available in , including ebooks by speci c subject new in 2014 new in 2014 new in 2014 from the Continuum archive ■ Download and print chapter PDFs ■ Instant access to s of key works, without DRM restriction easily navigable by research topic ■ Cite, share and personalize content RECOMMEND TO YOUR LIBRARY & SIGN UP FOR NEWS ▶ 9781623561222 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623561833 $14.95 | £8.99 9781623564230 $14.95 | £8.99 REGISTER FOR LIBRARY TRIALS AND QUOTES ▶ bloomsbury.com • 333sound.com • @333books [email protected] www.bloomsburycollections.com BC ad A5 (music).indd 1 08/10/2013 14:19 CONTENTS eBooks Contents eBook availability is indicated under each book entry: Individual eBook: available for your e-reader. -

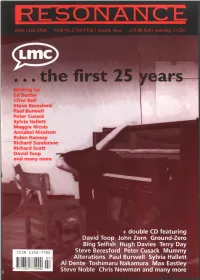

+ Double CD Featuring David Toop John Zorn Ground-Zero Bing

W riting by Ed Baxter Clive Bell Steve Beresford Paul Burwell Peter Cusack Sylvia Hallett Maggie Nicols Annabel Nicolson Robin Ramsay Richard Sanderson Richard Scott David Toop - and many more + double CD featuring David Toop John Zorn Ground-Zero Bing Selfish Hugh Davies Terry Day ISSN 1352-772X Steve Beresford Peter Cusack Mummy 977135277299007 Alterations Paul Burwell Sylvia Hallett Al Dente Toshimaru Nakamura Max Eastley 9 771352 772990 Steve Noble Chris Newman and many more ances. O ne night I turned up and poked Maggie telling a story about a dancing my nose in to see what was happening and My favourite LMC moment female slug in the candlelight and going was lured in by a man playing serene C A R O L I N E K R A A B E L completely beyond improvisation into a meditational music by applying a piece of sort of egoless free association that held expanded polystyrene to a rotating glass the listeners embarrassed and enthralled, table [B a rry Leigh]. Max Eastley’s long almost frightened. bowed instruments and mechanical opera Keiji Haino’s acoustic percussion solo at characters were as amazing to see as to one LMC festival. Haco’s microphone hear. I remember a performance by what feedback in a teapot - along with Charles may or may not have been the Bow Hayward’s Doppler on a cheap cassette Gamelan, where Paul Burwell and a machine, the only LMC performance I’ve woman coated each other in gloss paint - personally witnessed that really dealt in any having found it hard enough to clean my way with the BASIC paradoxes of own body o f a coat o f acrylic after an electricity and music. -

Not Necessarily “English Music”

LMJ 11 CD Not Necessarily “English Music” curated by David Toop Leonardo Music Journal CD Series Volume 11 CD ONE 8. MUSIC FOR THREE SPRINGS 5:03 Composer/performer: Hugh Davies (amplified springs) Recorded in 1977. Digital transfer by Paradigm Discs. 1. LIVE AT THE ROYAL COLLEGE OF ART 6:24 Performers: AMM 9. PIANO MUSICS I & II 5:13 Eddie Prévost, Keith Rowe, Cornelius Cardew, Lou Gare, Lawrence Composer/performer: Robert Worby Sheaff Recorded 1975. Recorded at the Royal College of Art, London, 28 March 1966. © 2001 Matchless Records & Publishing. 10. PLUM 7:07 Performers: Lol Coxhill (soprano sax, Watkins Copy Cat Echo), Steve 2. WIND FLUTES URBAN 3:17 Miller (electric piano) Sound sculptures constructed by Max Eastley Recorded live in England, 1973. Recorded in London, 1975. 11. SEARCH AND REFLECT 6:09 3. PERFORMANTS 6:40 Composer: John Stevens Composers/performers: Intermodulation Performers: Spontaneous Music Orchestra Roger Smalley, Tim Souster, Robin Thompson, Peter Britton Probable line-up: John Stevens, Lou Gare, Trevor Watts, Ron Recorded at Ely Cathedral, England, 6 July 1971. Recording prepared Herman, Paul Burwell, David Toop, Christopher Small, Herman by Simon Emmerson. Hauge, Chris Turner, Ye Min, Mike Barton Recorded at the Little Theatre Club, London, 18 January 1972. Re- 4. WEDGED INTO RELEASE 3:27 corded by David Toop. Digital conversion by Dave Hunt. Composer/performer: Frank Perry (percussion) Recorded at Command Studios, London, 1971. 12. PART 3 6:42 Performers: The People Band 5. PIECE FOR CELLO AND ACCORDION 2:50 Terry Day, Mel Davis, Lyn Dobson, Eddie Edem, Tony Edwards, Mick Composer: Michael Parsons Figgis, Frank Flowers, Terry Halman, Russ Herncy, George Khan Performers: Michael Parsons (cello), Howard Skempton (accordion) Recorded in London, 21 March 1968. -

Artofimprovisers Catalogue 01.Pdf

In Art of Improvisers Group Show, at Cafe Oto’s Project Space, from 7 to 17 of May 2015, we presented the art and archives of some of the pioneers of free improvisation in London. The exhibition featured content by musicians and artists Terry Day (artwork), Evan Parker (collages), Steve Beresford (archives), George Khan (clothes), David Toop (archives), Max Eastley (installation), Gina Southgate (paintings), a film by Anne Bean (Taps) and extracts of the upcoming film Unpredictable by Blanca Regina. The programme included a talk with live painted timeline about the history of free improvisation in UK, with speakers Steve Beresford, Evan Parker and Terry Day. Gina Southgate and Blanca Regina were painting the timeline. There were also two workshops: Material Studies with Matthias Kispert and Blanca Regina and Techniques in playing balloons and making pipes with Terry Day. Visual arts and music are intimately connected. Many musicians are also visual artists: that is what caught our attention. We wanted to know more about it. We focussed on these connections and the archives and exhibition looked at how one practice feeds into the other. Free improvisation is present in everyday life, not just in the arts. In the exhibition we worked together, transforming the space and selecting the artwork, in many cases framing it. Its interesting how we and some of our ideas shift when the medium changes. We ourselves were transformed through the process of the encounter and from working with the artworks. The point was to get together and to discover more about each others’ practice, and the history and present day situation for free improvisation and art in London. -

Steve Beresford, Phil Minton, Aleks Kolkowski and Sean Williams Perform Pieces by Hugh Davies

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Data Leeds Repository (University of Leeds) Steve Beresford, Phil Minton, Aleks Kolkowski and Sean Williams perform pieces by Hugh Davies plus solo and group improvisations Sunday 18 October 4:00pm Programme £1 PROGRAMME Hugh Davies – The Birth of Live Electronic Music (1971) Hugh Davies – Voice (1969) [vocalist: Phil Minton] Hugh Davies – Not to be Loaded with Fish (1968-9) [Phil Minton] Steve Beresford – Voice (1974) Hugh Davies – Not to be Loaded with Fish (1968-9) [Steve Beresford] Steve Beresford – improvised set Steve Beresford & Phil Minton – improvised set Steve Beresford, Phil Minton, Aleks Kolkowski & Sean Williams – improvised set Hugh Davies – The Birth of Live Electronic Music (1971) [second performance] PROGRAMME NOTES Hugh Davies – The Birth of Live Electronic Music (1971) for Stroh violin, two noise-makers, and acoustic mixer Phil Minton - Voice; Steve Beresford - Objects; Sean Williams - Mixing & Aleks Kolkowski - Stroh Violin. Realisation by Aleks Kolkowski. This is a music theatre piece in which four performers imitate the sounds of a recording on 78-rpm disc being played back on a wind-up gramophone— including the scratches and crackles, and various other idiosyncrasies that are characteristic of this kind of playback medium. The following are extracts from Davies’s own performance instructions: This work is a performance that involves a pre-electric equivalent of a live electronic amplification system, using as its principal sound source an early 20th century ‘violin with horn.’ It reverses the normal practice of making a special studio recording following a live performance. -

David Toop Is a Musician, Writer and Sound Curator Based in London

david toop is a musician, writer and sound curator based in London. The author of seven books on music, sound and listening, he is currently Professor of Audio Culture and Improvisation at London College of Communication. Praise for Ocean of Sound “As styles of music multiply and divide at an accelerating pace, Ocean of Sound challenges the way we hear, and more importantly, how we interpret what we hear around us.” Daily Telegraph “Ocean of Sound shatters consensual reality with a cumulative force that’s both frightening and compelling. Buy it, read it and let it remix your head.” i-D “Its parallels aren’t music books at all, but rather Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Michel Leiris’s Afrique Phantôme, William Gibson’s Neuromancer … David Toop is our Calvino and our Leiris, our Gibson. Ocean of Sound is as alien as the twentieth century, as utterly Now as the twenty-first. An essential mix.” The Wire “An extraordinary and revelatory book, Ocean of Sound reads like an alternative history of twentieth-century music, tracking the passage of organised sound into strange and new environments of vapour and abstraction.” Tony Herrington “At the end of the millennium, we can see two trends in music, one proactive, the other reactive … Toop’s Ocean of Sound brilliantly elaborates both these processes, like sonic fact for our sci-fi present, a Martian Chronicle from this Planet Earth.” The Face “This Encyclopaedia of Heavenly Music is an heroic endeavour brought off with elegance and charm. The play of ideas is downright musical and, vitally, the author writes like a mad enthusiast rather than a snob.” NME “Always the rigorous pluralist, [Toop] sees no reason not to expect wisdoms from rival cultures, tribal or club, nor emptiness or stupidity either. -

SINISTER RESONANCE This Page Intentionally Left Blank SINISTER RESONANCE the Mediumship of the Listener

SINISTER RESONANCE This page intentionally left blank SINISTER RESONANCE The Mediumship of the Listener David Toop 2010 The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc 80 Maiden Lane, New York, NY 10038 The Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd The Tower Building, 11 York Road, London SE1 7NX www.continuumbooks.com Copyright © 2010 by David Toop All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Toop, David. Sinister resonance : the mediumship of the listener / by David Toop. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978- 1-4411-4972-5 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1- 4411-4972-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Music—Physiological effect. 2. Auditory perception. 3. Musical perception. I. Title. ML3820.T66 2010 781’.1—dc22 2009047734 ISBN: 978- 1-4411-4972-5 Typeset by Pindar NZ, Auckland, New Zealand Printed in the United States of America Contents Prelude: Distant Music vii PART I: Aeriel — Notes Toward a History of Listening 1 1. Drowned by voices 3 2. Each echoing opening; each muffl ed closure 27 3. Dark senses 39 4. Writhing sigla 53 5. The jagged dog 58 PART II: Vessels and Volumes 65 6. Act of silence 67 7. Art of silence 73 8. A conversation piece 107 PART III: Spectral 123 9. Chair creaks, but no one sits there 125 PART IV: Interior Resonance 179 10. Snow falling on snow 181 Coda: Distant Music 231 Acknowledgements 234 Notes 237 Index 253 v For Paul Burwell (1949–2007) drumming in some smoke- fi lled region — ‘And then the sea was closed again, above us’ — and Doris Toop (1912–2008) Prelude: Distant Music (on the contemplation of listening) Out of deep dreamless sleep I was woken, startled by a hollow resonance, a sudden impact of wood on wood.