Tick-Borne Disease, Excluding Lyme and Relapsing Fever

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Official Nh Dhhs Health Alert

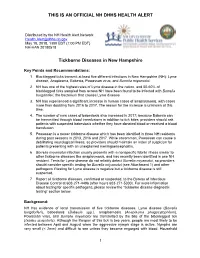

THIS IS AN OFFICIAL NH DHHS HEALTH ALERT Distributed by the NH Health Alert Network [email protected] May 18, 2018, 1300 EDT (1:00 PM EDT) NH-HAN 20180518 Tickborne Diseases in New Hampshire Key Points and Recommendations: 1. Blacklegged ticks transmit at least five different infections in New Hampshire (NH): Lyme disease, Anaplasma, Babesia, Powassan virus, and Borrelia miyamotoi. 2. NH has one of the highest rates of Lyme disease in the nation, and 50-60% of blacklegged ticks sampled from across NH have been found to be infected with Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. 3. NH has experienced a significant increase in human cases of anaplasmosis, with cases more than doubling from 2016 to 2017. The reason for the increase is unknown at this time. 4. The number of new cases of babesiosis also increased in 2017; because Babesia can be transmitted through blood transfusions in addition to tick bites, providers should ask patients with suspected babesiosis whether they have donated blood or received a blood transfusion. 5. Powassan is a newer tickborne disease which has been identified in three NH residents during past seasons in 2013, 2016 and 2017. While uncommon, Powassan can cause a debilitating neurological illness, so providers should maintain an index of suspicion for patients presenting with an unexplained meningoencephalitis. 6. Borrelia miyamotoi infection usually presents with a nonspecific febrile illness similar to other tickborne diseases like anaplasmosis, and has recently been identified in one NH resident. Tests for Lyme disease do not reliably detect Borrelia miyamotoi, so providers should consider specific testing for Borrelia miyamotoi (see Attachment 1) and other pathogens if testing for Lyme disease is negative but a tickborne disease is still suspected. -

Parinaud's Oculoglandular Syndrome

Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease Case Report Parinaud’s Oculoglandular Syndrome: A Case in an Adult with Flea-Borne Typhus and a Review M. Kevin Dixon 1, Christopher L. Dayton 2 and Gregory M. Anstead 3,4,* 1 Baylor Scott & White Clinic, 800 Scott & White Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA; [email protected] 2 Division of Critical Care, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA; [email protected] 3 Medical Service, South Texas Veterans Health Care System, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA 4 Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, University of Texas Health, San Antonio, 7703 Floyd Curl Drive, San Antonio, TX 78229, USA * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +1-210-567-4666; Fax: +1-210-567-4670 Received: 7 June 2020; Accepted: 24 July 2020; Published: 29 July 2020 Abstract: Parinaud’s oculoglandular syndrome (POGS) is defined as unilateral granulomatous conjunctivitis and facial lymphadenopathy. The aims of the current study are to describe a case of POGS with uveitis due to flea-borne typhus (FBT) and to present a diagnostic and therapeutic approach to POGS. The patient, a 38-year old man, presented with persistent unilateral eye pain, fever, rash, preauricular and submandibular lymphadenopathy, and laboratory findings of FBT: hyponatremia, elevated transaminase and lactate dehydrogenase levels, thrombocytopenia, and hypoalbuminemia. His condition rapidly improved after starting doxycycline. Soon after hospitalization, he was diagnosed with uveitis, which responded to topical prednisolone. To derive a diagnostic and empiric therapeutic approach to POGS, we reviewed the cases of POGS from its various causes since 1976 to discern epidemiologic clues and determine successful diagnostic techniques and therapies; we found multiple cases due to cat scratch disease (CSD; due to Bartonella henselae) (twelve), tularemia (ten), sporotrichosis (three), Rickettsia conorii (three), R. -

Multiple Pruritic Papules from Lone Star Tick Larvae Bites

OBSERVATION Multiple Pruritic Papules From Lone Star Tick Larvae Bites Emily J. Fisher, MD; Jun Mo, MD; Anne W. Lucky, MD Background: Ticks are the second most common vec- was treated with permethrin cream and the lesions re- tors of human infectious diseases in the world. In addi- solved over the following 3 weeks without sequelae. The tion to their role as vectors, ticks and their larvae can also organism was later identified as the larva of Amblyomma produce primary skin manifestations. Infestation by the species, the lone star tick. larvae of ticks is not commonly recognized, with only 3 cases reported in the literature. The presence of mul- Conclusions: Multiple pruritic papules can pose a di- tiple lesions and partially burrowed 6-legged tick larvae agnostic challenge. The patient described herein had an can present a diagnostic challenge for clinicians. unusually large number of pruritic papules as well as tick larvae present on her skin. Recognition of lone star tick Observation: We describe a 51-year-old healthy woman larvae as a cause of multiple bites may be helpful in simi- who presented to our clinic with multiple erythematous lar cases. papules and partially burrowed organisms 5 days after exposure to a wooded area in southern Kentucky. She Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:491-494 ATIENTS WITH MULTIPLE PRU- acteristic clinical and diagnostic features of ritic papules that appear to be infestation by larvae of Amblyomma species bitespresentachallengetothe and may help clinicians make similar di- clinician. We present a case of agnoses in the future. a healthy 51-year-old woman whowasbittenbymultiplelarvaeofthetick, P REPORT OF A CASE Amblyomma species, most likely A ameri- canum or the lone star tick. -

Blood Smear Analysis in Babesiosis, Ehrlichiosis, Relapsing Fever, Malaria, and Chagas Disease

REVIEW STEVE M. BLEVINS, MD RONALD A. GREENFIELD, MD* MICHAEL S. BRONZE, MD CME Assistant Professor of Medicine, Section Professor of Medicine, Section of Infectious Professor of Medicine, Section of Infectious CREDIT of General Internal Medicine, Department Diseases, Department of Medicine, University Diseases, Chair of Department of Medicine, of Medicine, University of Oklahoma of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and the University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City Oklahoma City Veterans Administration and the Oklahoma City Veterans Administration Medical Center Medical Center Blood smear analysis in babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, relapsing fever, malaria, and Chagas disease ■ ABSTRACT LOOD SMEAR ANALYSIS, while commonly B used to evaluate hematologic condi- Blood smear analysis is especially useful for diagnosing tions, is infrequently used to diagnose infec- five infectious diseases: babesiosis, ehrlichiosis, relapsing tious diseases. This is because of the rarity of fever due to Borrelia infection, malaria, and American diseases for which blood smear analysis is indi- trypanosomiasis (Chagas disease). It should be performed cated. Consequently, such testing is often in patients with persistent or recurring fever or in those overlooked when it is diagnostically impor- who have traveled to the developing world or who have tant. a history of tick exposure, especially if accompanied by Nonspecific changes may include mor- hemolytic anemia, thrombocytopenia, or phologic changes in leukocytes and erythro- 1 hepatosplenomegaly. cytes (eg, toxic granulations, macrocytosis). And with certain pathogens, identifying ■ KEY POINTS organisms in a peripheral blood smear allows for a rapid diagnosis. In the United States, malaria and American This paper discusses the epidemiology, trypanosomiasis principally affect travelers from the clinical manifestations, laboratory findings, developing world. -

Fournier's Gangrene Caused by Listeria Monocytogenes As

CASE REPORT Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes as the primary organism Sayaka Asahata MD1, Yuji Hirai MD PhD1, Yusuke Ainoda MD PhD1, Takahiro Fujita MD1, Yumiko Okada DVM PhD2, Ken Kikuchi MD PhD1 S Asahata, Y Hirai, Y Ainoda, T Fujita, Y Okada, K Kikuchi. Une gangrène de Fournier causée par le Listeria Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes as the monocytogenes comme organisme primaire primary organism. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2015;26(1):44-46. Un homme de 70 ans ayant des antécédents de cancer de la langue s’est présenté avec une gangrène de Fournier causée par un Listeria A 70-year-old man with a history of tongue cancer presented with monocytogenes de sérotype 4b. Le débridement chirurgical a révélé un Fournier’s gangrene caused by Listeria monocytogenes serotype 4b. adénocarcinome rectal non diagnostiqué. Le patient n’avait pas Surgical debridement revealed undiagnosed rectal adenocarcinoma. d’antécédents alimentaires ou de voyage apparents, mais a déclaré The patient did not have an apparent dietary or travel history but consommer des sashimis (poisson cru) tous les jours. reported daily consumption of sashimi (raw fish). L’âge avancé et l’immunodéficience causée par l’adénocarcinome rec- Old age and immunodeficiency due to rectal adenocarcinoma may tal ont peut-être favorisé l’invasion directe du L monocytogenes par la have supported the direct invasion of L monocytogenes from the tumeur. Il s’agit du premier cas déclaré de gangrène de Fournier tumour. The present article describes the first reported case of attribuable au L monocytogenes. Les auteurs proposent d’inclure la con- Fournier’s gangrene caused by L monocytogenes. -

Kellie ID Emergencies.Pptx

4/24/11 ID Alert! recognizing rapidly fatal infections Susan M. Kellie, MD, MPH Professor of Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases, UNMSOM Hospital Epidemiologist UNMHSC and NMVAHCS Fever and…. Rash and altered mental status Rash Muscle pain Lymphadenopathy Hypotension Shortness of breath Recent travel Abdominal pain and diarrhea Case 1. The cross-country trucker A 30 year-old trucker driving from Oklahoma to California is hospitalized in Deming with fever and headache He is treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics, but deteriorates with obtundation, low platelet count, and a centrifugal petechial rash and is transferred to UNMH 1 4/24/11 What is your diagnosis? What is the differential diagnosis of fever and headache with petechial rash? (in the US) Tickborne rickettsioses ◦ RMSF Bacteria ◦ Neisseria meningitidis Key diagnosis in this case: “doxycycline deficiency” Key vector-borne rickettsioses treated with doxycycline: RMSF-case-fatality 5-10% ◦ Fever, nausea, vomiting, myalgia, anorexia and headache ◦ Maculopapular rash progresses to petechial after 2-4 days of fever ◦ Occasionally without rash Human granulocytotropic anaplasmosis (HGA): case-fatality<1% Human monocytotropic ehrlichiosis (HME): case fatality 2-3% 2 4/24/11 Lab clues in rickettsioses The total white blood cell (WBC) count is typicallynormal in patients with RMSF, but increased numbers of immature bands are generally observed. Thrombocytopenia, mild elevations in hepatic transaminases, and hyponatremia might be observed with RMSF whereas leukopenia -

Characterization of the Interaction Between R. Conorii and Human

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 4-5-2018 Characterization of the Interaction Between R. Conorii and Human Host Vitronectin in Rickettsial Pathogenesis Abigail Inez Fish Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Bacteria Commons, Bacteriology Commons, Biology Commons, Immunology of Infectious Disease Commons, and the Pathogenic Microbiology Commons Recommended Citation Fish, Abigail Inez, "Characterization of the Interaction Between R. Conorii and Human Host Vitronectin in Rickettsial Pathogenesis" (2018). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 4566. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4566 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. CHARACTERIZATION OF THE INTERACTION BETWEEN R. CONORII AND HUMAN HOST VITRONECTIN IN RICKETTSIAL PATHOGENESIS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Interdepartmental Program in Biomedical and Veterinary Medical Sciences Through the Department of Pathobiological Sciences by Abigail Inez -

A Fatal Case of Necrotising Fasciitis of the Eyelid

Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.72.6.428 on 1 June 1988. Downloaded from British Journal of Ophthalmology, 1988, 72, 428-431 A fatal case of necrotising fasciitis of the eyelid R WALTERS From Southampton Eye Hospital, Wilton A venue, Southampton S09 4XW SUMMARY A fatal case of necrotising fasciitis in a 35-year-old man is described and the differential diagnosis and management discussed. Necrotising fasciitis is a potentially fatal skin were taken. The Gram stain revealed Gram-positive infection which is being increasingly recognised as an cocci. He was then treated with intravenous underdiagnosed condition. It requires prompt diag- cefotaxime and gentamicin and topical chlor- nosis, investigation, and treatment. Early surgical amphenicol and gentamicin drops. Because of the debridement is, in combination with suitable intra- poor visual acuity of the right eye it was thought that venous antibiotics, the mainstay of treatment. an orbital cellulitis could not be excluded despite the normal eye movements and absence of proptosis. He Case report was therefore transferred to the General Hospital under the care of an ear, nose, and throat consultant In December 1985 a previously fit 35-year-old factory in order to exclude underlying sinus disease and an manager was referred by his general practitioner to associated abscess. the Casualty Department of the Southampton Eye Skull x-rays (including sinus views) revealed no Hospital with a 12-hour history of increasing redness abnormality and he was therefore continued on his and swelling of his right upper lid. He said that two medical treatment (with the addition of intravenous http://bjo.bmj.com/ days previously he had been poked in the same eye by metronidazole), the presumed diagnosis being his daughter (who had been playing with her guinea- preseptal cellulitis. -

Bitten Enhance.Pdf

bitten. Copyright © 2019 by Kris Newby. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address HarperCollins Publishers, 195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007. HarperCollins books may be purchased for educational, business, or sales pro- motional use. For information, please email the Special Markets Department at [email protected]. first edition Frontispiece: Tick research at Rocky Mountain Laboratories, in Hamilton, Mon- tana (Courtesy of Gary Hettrick, Rocky Mountain Laboratories, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases [NIAID], National Institutes of Health [NIH]) Maps by Nick Springer, Springer Cartographics Designed by William Ruoto Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Newby, Kris, author. Title: Bitten: the secret history of lyme disease and biological weapons / Kris Newby. Description: New York, NY: Harper Wave, [2019] Identifiers: LCCN 2019006357 | ISBN 9780062896278 (hardback) Subjects: LCSH: Lyme disease— History. | Lyme disease— Diagnosis. | Lyme Disease— Treatment. | BISAC: HEALTH & FITNESS / Diseases / Nervous System (incl. Brain). | MEDICAL / Diseases. | MEDICAL / Infectious Diseases. Classification: LCC RC155.5.N49 2019 | DDC 616.9/246—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019006357 19 20 21 22 23 lsc 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Appendix I: Ticks and Human Disease Agents -

Illness Reporting Log for Temporary Events and Volunteers

1020 6th Street SE Cedar Rapids, IA 52401 PH: 319-892-6000 www.linncounty.org/603/Food-Safety REPORTING OF ILLNESS FORM Worker Sign-in Sheet The purpose of this form is to inform food workers of their responsibility to notify the person in charge when they experience any of the health conditions listed below. The person in charge must take appropriate steps to prevent the transmission of foodborne illness. I AGREE TO REPORT TO THE PERSON IN CHARGE: Any onset of the following symptoms, either while at work or outside of work, including the onset date: 1. Diarrhea 2. Vomiting 3. Jaundice 4. Sore throat with fever 5. Infected cuts or wounds, or lesions containing pus on the hand, wrist , an exposed body part, or other body part and the cuts, wounds, or lesions are not properly covered (such as boils and infected wounds, however small) Medical Diagnosis: Whenever diagnosed as being ill with Norovirus, typhoid fever (Salmonella Typhi), non-typhoidal Salmonella, shigellosis (Shigella spp. infection), Escherichia coil 0157:H7 or other Enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) or Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infection or Hepatitis A (hepatitis A virus infection) Exposure to Foodborne Pathogens: 1. Exposure to or suspicion of causing any confirmed disease outbreak of Norovirus, typhoid fever, shigellosis, E. coli 0157:H7 or other Enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) or Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infection, or Hepatitis A. 2. A household member diagnosed with Norovirus, typhoid fever, shigellosis, E. coli 0157:H7 or other Enterohemorrhagic (EHEC) or Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infection, or Hepatitis A. 3. A household member attending or working in a setting experiencing a confirmed disease outbreak of Norovirus, typhoid fever, shigellosis, E. -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

CD Alert Monthly Newsletter of National Centre for Disease Control, Directorate General of Health Services, Government of India

CD Alert Monthly Newsletter of National Centre for Disease Control, Directorate General of Health Services, Government of India May - July 2009 Vol. 13 : No. 1 SCRUB TYPHUS & OTHER RICKETTSIOSES it lacks lipopolysaccharide and peptidoglycan RICKETTSIAL DISEASES and does not have an outer slime layer. It is These are the diseases caused by rickettsiae endowed with a major surface protein (56kDa) which are small, gram negative bacilli adapted and some minor surface protein (110, 80, 46, to obligate intracellular parasitism, and 43, 39, 35, 25 and 25kDa). There are transmitted by arthropod vectors. These considerable differences in virulence and organisms are primarily parasites of arthropods antigen composition among individual strains such as lice, fleas, ticks and mites, in which of O.tsutsugamushi. O.tsutsugamushi has they are found in the alimentary canal. In many serotypes (Karp, Gillian, Kato and vertebrates, including humans, they infect the Kawazaki). vascular endothelium and reticuloendothelial GLOBAL SCENARIO cells. Commonly known rickettsial disease is Scrub Typhus. Geographic distribution of the disease occurs within an area of about 13 million km2 including- The family Rickettsiaeceae currently comprises Afghanistan and Pakistan to the west; Russia of three genera – Rickettsia, Orientia and to the north; Korea and Japan to the northeast; Ehrlichia which appear to have descended Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, and northern from a common ancestor. Former members Australia to the south; and some smaller of the family, Coxiella burnetii, which causes islands in the western Pacific. It was Q fever and Rochalimaea quintana causing first observed in Japan where it was found to trench fever have been excluded because the be transmitted by mites.