African Studies in the Digital Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Life and Contribution of the Late Benedicto K. M. Kiwanuka to the Political History of Uganda”

“The Life and Contribution of the Late Benedicto K. M. Kiwanuka to the Political History of Uganda” By Paul K. Ssemogerere, Former Deputy Prime Minister & Retired President of the Democratic Party A Lecture in Memory of Benedicto Kiwanuka Organized by the Foundation for African Development and the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung on 13th October 2015, Hotel Africana 1. Introduction I believe I am speaking for all present, when I express sincere appreciation to the leadership of the Foundation for African Development (FAD), who, in collaboration with the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung (KAS) of Germany, instituted this series of Annual Memorial Lectures/Dialogues in happy memory of someone who lived and worked under great difficulties but, guided by noble principles, and propelled by sustained personal endeavor to lead in order to serve, rose to great heights, and eventually leaving his star shining brightly for all of us long after his awful extra- judicial execution – an execution orchestrated by fellow-men held captive by envy and personal insecurity. I welcome today’s main presentation for the Dialogue on “What needs to be done to avert the risk of election violence before, during and after the 2016 General Elections in Uganda”, for three main reasons: • First, because anxiety about the likelihood of violence breaking out with disastrous consequences is well founded; there are simply too many things wrong about the forthcoming election while, at the same time, there is, so far, an apparent lack of genuine interest to address them seriously and objectively -

A Foreign Policy Determined by Sitting Presidents: a Case

T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI ANKARA, 2019 T.C. ANKARA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS A FOREIGN POLICY DETERMINED BY SITTING PRESIDENTS: A CASE STUDY OF UGANDA FROM INDEPENDENCE TO DATE PhD Thesis MIRIAM KYOMUHANGI SUPERVISOR Prof. Dr. Çınar ÖZEN ANKARA, 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................ i ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................... iv FIGURES ................................................................................................................... vi PHOTOS ................................................................................................................... vii INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTER ONE UGANDA’S JOURNEY TO AUTONOMY AND CONSTITUTIONAL SYSTEM I. A COLONIAL BACKGROUND OF UGANDA ............................................... 23 A. Colonial-Background of Uganda ...................................................................... 23 B. British Colonial Interests .................................................................................. 32 a. British Economic Interests ......................................................................... -

Professor Mondo Kagonyera H.E. YOWERI K.MUSEVENI THE

Speech by Professor Mondo Kagonyera Chancellor, Makerere University, Kampala AT THE SPECIAL CONGREGATION FOR THE CONFERMENT OF HONORARY DOCTOR OF LAWS (HONORIS CAUSA) UPON H.E. YOWERI K.MUSEVENI THE PRESIDENT OFUGANDA AND H.E. RASHID MFAUME KAWAWA (POSTHUMOUS), FORMER 1ST VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA DATE: 12TH DECEMBER 2010 AT VENUE: FREEDOM SQUARE, MAKERERE UNIVERSITY, KAMPALA Your Excellency Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, President of the Republic of Uganda The First Lady, Hon Janet K. Museveni, MP The Family of His Excellency Late Rashid Mfaume Kawawa Your Excellency, Professor Gilbert Bukenya, Vice President of Uganda, Right Honorable Professor Apolo Nsibambi, Prime Minister of Uganda, Your Excellencies Ambassadors and High Commissioners Honorable Ministers and Members of Parliament Professor Venansius Baryamureeba, Vice Chancellor, Our Special Guests from Egerton University, Kenya, & the Pan African Agribusiness & Ago Industry Consortium, (PanAAC), Kenya, Members of the University Council Members of Senate Distinguished Guests Members of Staff Ladies and Gentlemen It gives me great pleasure to welcome you all, once again, to this special congregation of Makerere University in the Freedom Square. Your Excellency, allow me once again to thank you very much for having me the great honor of heading the great Makerere University. This is a historic occasion for me as the first Chancellor of Makerere University to confer the Honorary Doctorate Degree upon His Excellency President Yoweri K. Museveni, who is also the Visitor of Makerere University. I must also express my appreciation of the fact that busy as you are now, you have found time to personally honor this occasion. INTRODUCTION As Chancellor, I shall constitute a special congregation of Makerere University to confer the Doctor of Laws (Honoris Causa) upon H.E. -

Political Theologies in Late Colonial Buganda

POLITICAL THEOLOGIES IN LATE COLONIAL BUGANDA Jonathon L. Earle Selwyn College University of Cambridge This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Preface This dissertation is the result of my own work and includes nothing which is the outcome of work done in collaboration except where specifically indicated in the text. It does not exceed the limit of 80,000 words set by the Degree Committee of the Faculty of History. i Abstract This thesis is an intellectual history of political debate in colonial Buganda. It is a history of how competing actors engaged differently in polemical space informed by conflicting histories, varying religious allegiances and dissimilar texts. Methodologically, biography is used to explore three interdependent stories. First, it is employed to explore local variance within Buganda’s shifting discursive landscape throughout the longue durée. Second, it is used to investigate the ways that disparate actors and their respective communities used sacred text, theology and religious experience differently to reshape local discourse and to re-imagine Buganda on the eve of independence. Finally, by incorporating recent developments in the field of global intellectual history, biography is used to reconceptualise Buganda’s late colonial past globally. Due to its immense source base, Buganda provides an excellent case study for writing intellectual biography. From the late nineteenth century, Buganda’s increasingly literate population generated an extensive corpus of clan and kingdom histories, political treatises, religious writings and personal memoirs. As Buganda’s monarchy was renegotiated throughout decolonisation, her activists—working from different angles— engaged in heated debate and protest. -

Exclusionary Elite Bargains and Civil War Onset: the Case of Uganda

Working Paper no. 76 - Development as State-making - EXCLUSIONARY ELITE BARGAINS AND CIVIL WAR ONSET: THE CASE OF UGANDA Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre August 2010 Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) Copyright © S. Lindemann, 2010 This document is an output from a research programme funded by UKaid from the Department for International Development. However, the views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Crisis States Research Centre Exclusionary elite bargains and civil war onset: The case of Uganda Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre Uganda offers almost unequalled opportunities for the study of civil war1 with no less than fifteen cases since independence in 1962 (see Figure 1) – a number that makes it one of the most conflict-intensive countries on the African continent. The current government of Yoweri Museveni has faced the highest number of armed insurgencies (seven), followed by the Obote II regime (five), the Amin military dictatorship (two) and the Obote I administration (one).2 Strikingly, only 17 out of the 47 post-colonial years have been entirely civil war free. 7 NRA 6 UFM FEDEMO UNFR I FUNA 5 NRA UFM UNRF I FUNA wars 4 UPDA LRA LRA civil HSM ADF ADF of UPA WNBF UNRF II 3 Number FUNA LRA LRA UNRF I UPA WNBF 2 UPDA HSM Battle Kikoosi Maluum/ UNLA LRA LRA 1 of Mengo FRONASA 0 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Figure 1: Civil war in Uganda, 1962-2008 Source: Own compilation. -

HOSTILE to DEMOCRACY the Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda

HOSTILE TO DEMOCRACY The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ London $$$ Brussels Copyright 8 August 1999 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-239-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-65985 Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail:[email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. -

Black Laws Matter Benedicto Kiwanuka’S Legacy and the Rule of Law in the ‘New Normal’

1 BLACK LAWS MATTER BENEDICTO KIWANUKA’S LEGACY AND THE RULE OF LAW IN THE ‘NEW NORMAL’ KEYNOTE ADDRESS BY DR. BUSINGYE KABUMBA, LECTURER OF LAW, MAKERERE UNIVERSITY AT THE 3RD BENEDICTO KIWANUKA MEMORIAL LECTURE 21ST SEPTEMBER, 2020 THE HIGH COURT, KAMPALA 2 My Lord The Hon. Alfonse Chigamoy Owiny-Dollo, The Chief Justice of the Republic of Uganda, The Hon. Bart Magunda Katureebe, The Chief Justice of the Republic of Uganda, The Hon. The Deputy Chief Justice, The Honorable Minister of Justice and Constitutional Affairs, The Hon. The Principal Judge, My Lords the Justices and Judges, The Chief Registrar, The Family of the Late Benedicto Kiwanuka, Heads of JLOS Institutions, Permanent Secretaries, Your Worships, The President of the Uganda Judicial Officers Association, The President of the Uganda Law Society, Invited Guests, Ladies and Gentlemen. 1.0 Introduction I thank the Chief Justice Alfonse Chigamoy Owiny-Dollo for inviting me to give this lecture in memory of the first Ugandan Chief Justice of our country, the late Benedicto Kagimu Mugumba Kiwanuka. I am deeply honoured to have been so invited. In the first place because of the immense stature of the man to whom this day is dedicated. Secondly, given the illustrious nature of the previous two key note speakers (Chief Justice Samuel William Wako Wambuzi – three- time Chief Justice of Uganda and Chief Justice Willy Mutunga, the first Chief Justice of Kenya under the 2010 Constitution of that country). I am keenly aware of the trust exemplified by this invitation, and do hope to try to live up to it. -

Eine Sozialgeschichte Des Krieges Im Luwero-Dreieck, Uganda 1981-1986

"War came to our place" – Eine Sozialgeschichte des Krieges im Luwero-Dreieck, Uganda 1981 – 1986 Von der Gemeinsamen Fakultät für Geistes- und Sozialwissenschaften der Universität Hannover zur Erlangung des Grades eines DOKTORS DER PHILOSOPHIE Dr. phil. genehmigte Dissertation von Frank Schubert, M.A. geboren am 02.03.1962, in Brilon 2005 2 Referent: Prof. Bley Korreferentin: Prof. Behrend (Universität Köln) Vorsitzender: Prof. Gabbert Tag der Promotion: 30.10.2003 3 Abstract In der vorliegenden Arbeit untersuche ich die Handlungen und Motive von Zivilisten im Bürgerkrieg im so genannten Luwero-Dreieck in Uganda, in dem die Guerillabewegung der National Resistance Army (NRA) unter Yoweri Museveni ab 1981 gegen die Regierung Milton Obote und deren Armee, die Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA), kämpfte und schließlich 1986 die Macht übernahm. Diese Arbeit ist keine Militärgeschichte im klassischen Sinne, sondern versucht die Dynamik eines Guerillakrieges und seiner Gewalt nachzu- vollziehen. Dies schließt die besondere Bedeutung einer "Plünderöko- nomie" durch Soldaten ein. Auch die Rolle nationaler und internationaler Hilfsorganisationen wird untersucht. Besonderes Gewicht liegt auf den sozialen Prozessen innerhalb der vom Krieg betroffenen Bevölkerung, auf der Veränderung sozialer Netzwerke und der Relevanz innergesell- schaftlicher Differenzierungen und Konflikte. Hauptquellen für diese Arbeit sind erfahrungsgeschichtliche Interviews mit Zivilisten, auch mit jenen, die im Laufe des Krieges zu Soldaten wur- den. Diese Interviews -

Exclusionary Elite Bargains and Civil War Onset: the Case of Uganda

Working Paper no. 76 - Development as State-making - EXCLUSIONARY ELITE BARGAINS AND CIVIL WAR ONSET: THE CASE OF UGANDA Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre August 2010 Crisis States Working Papers Series No.2 ISSN 1749-1797 (print) ISSN 1749-1800 (online) Copyright © S. Lindemann, 2010 This document is an output from a research programme funded by UKaid from the Department for International Development. However, the views expressed are not necessarily those of DFID. Crisis States Research Centre Exclusionary elite bargains and civil war onset: The case of Uganda Stefan Lindemann Crisis States Research Centre Uganda offers almost unequalled opportunities for the study of civil war1 with no less than fifteen cases since independence in 1962 (see Figure 1) – a number that makes it one of the most conflict-intensive countries on the African continent. The current government of Yoweri Museveni has faced the highest number of armed insurgencies (seven), followed by the Obote II regime (five), the Amin military dictatorship (two) and the Obote I administration (one).2 Strikingly, only 17 out of the 47 post-colonial years have been entirely civil war free. 7 NRA 6 UFM FEDEMO UNFR I FUNA 5 NRA UFM UNRF I FUNA wars 4 UPDA LRA LRA civil HSM ADF ADF of UPA WNBF UNRF II 3 Number FUNA LRA LRA UNRF I UPA WNBF 2 UPDA HSM Battle Kikoosi Maluum/ UNLA LRA LRA 1 of Mengo FRONASA 0 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 Figure 1: Civil war in Uganda, 1962-2008 Source: Own compilation. -

Indigenous Language Programming and Citizen Participation in Ugandan Broadcasting: an Exploratory Study

INDIGENOUS LANGUAGE PROGRAMMING AND CITIZEN PARTICIPATION IN UGANDAN BROADCASTING: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY by MONICA BALYA CHIBITA submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF LITERATURE AND PHILOSOPHY in the subject of COMMUNICATION at the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA PROMOTER: PROF. PJ FOURIE JOINT PROMOTER: PROF. M RUTANGA JUNE 2006 i DECLARATION Student Number: 3439-444-3 I declare that ‘Indigenous language programming and citizen participation in Ugandan broadcasting: an exploratory study’ is my own work and that all the sources that I have used or quoted have been indicated and acknowledged by means of complete references. ………………………………………… …………………………. SIGNATURE DATE (MRS. MB CHIBITA) ii DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to my husband Mike Chibita, and to our children Benezeri, Maria, Semu and Joshua for understanding that this is something I needed to do, and that there was never going to be an ideal time for doing it, and to Dick and Ivy Otto and Deon and Teresa Conradie for providing that badly needed space for me to accomplish this task. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am extremely grateful to my promoter, Prof. Pieter J. Fourie for painstakingly working through the thesis with me and for his untiring guidance and support through the entire doctoral process. I have been inspired and matured greatly and by working with him. I am equally grateful to my co- promoter, Prof. Murindwa-Rutanga for his deep insights into the Ugandan political situation and issues of politics and culture, for his constant encouragement and for his practical advice. I thank Makerere University and the Carnegie Corporation of New York for financial support towards my tuition, travel and subsistence in South Africa and my research in Uganda, and the American Centre for their support in form of a book grant to the Mass Communication Department. -

Makerere the University Is Born

1 Makerere the University is Born Ever since it opened its doors with 14 boys and 5 instructors in 1922, Makerere, as seat of higher learning in East and Central Africa, has been in constant change. It started as a simple Technical School established by the Department of Education under the British Protectorate Government; appropriately located on a hill with a name which, according to legend, connotes daybreak. According to one version of the tale (and there could be several other versions), the hill we now know as Makerere was once a scene where history involving love and royalty was made. Some traditionalists believe the incident occurred during the reign of King Jjuuko in the late seventeenth Century. Legend has it that King Jjuuko had an eye for beautiful women and when he was told of a dazzlingly beautiful girl, Nalunga, living on the other side of the hill now called Makerere, he decided to go and look for her alone on foot. Traditionally, kings were not supposed to be seen walking around on foot in public. They had to be carried on the backs of special court servants. King Jjuuko had to sneak out of the palace in the dark of the night. Unfortunately, dawn found him on top of the hill now known as Makerere. In frustration the king exclaimed, “Oh, it is dawn”. Henceforth, the hill took on the name Makerere – the dawn of King Jjuuko. By coincidence, the British Protectorate Government chose to build an institution of higher learning on the same hill, in preference to Bombo, which signalled the dawn of new knowledge for Uganda and Africa. -

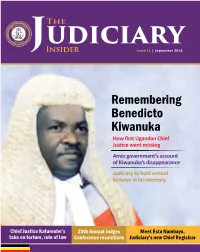

Remembering Benedicto Kiwanuka

DIC JU IA E R H Y T U GAN DA Issue 11 | September 2018 Remembering Benedicto Kiwanuka How first Ugandan Chief Justice went missing Amin government’s account of Kiwanuka’s disappearance Judiciary to hold annual lectures in his memory Chief Justice Katureebe’s 20th Annual Judges Meet Esta Nambayo, take on torture, rule of law Conference resolutions Judiciary’s new Chief Registrar PICTORIAL Remembering Benedicto Kiwanuka Benedicto Kiwanuka inspects a Guard of Honour by the Uganda Police shortly after being sworn-in as Uganda’s 1st Prime Minister, March 1, 1962. Kiwanuka (L) signs documents shortly after being sworn-in as Prime Minister. Kiwanuka with his wife, Maxencia Zalwango, at the swearing-in. Kiwanuka (L) meeting Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta (2nd L) in Nairobi for a conference on Independence for all Africa. Sir Fredrick Crawford, Governor of Uganda, congratulates Prime Kiwanuka at one of his political rallies in the early 1960s. Minister-elect, Kiwanuka, at Government House in Entebbe. The shell of the famous black Mercedes-Benz Ponton that Ben Kiwanuka drove. The Benedicto Kiwanuka family photo. Regina Kiwanuka, Ben Benedicto Kiwanuka’s Kiwanuka’s daughter. Passport photo. Chief Minister Kiwanuka (L) with wife and son (back), together with Advocate Kulubya, at Entebbe Airport leaving for London, 1961. Mrs. Mexencia Zalwango Kiwanuka. Some of Benedicto Kiwanuka’s children: Maxencia Kiwanuka- Kigongo and Amb. Maurice Kagimu-Kiwanuka. DIC JU IA E R H Y T U GAN DA INSIDE. Benedicto Kiwanuka’s legacy lives on 3 Judges Conference 2018 resolutions 4 Benedicto Kiwanuka: His life & times 6 When first Ugandan Chief Justice went missing t has been 46 years since Chief Justice Benedicto Kiwanuka was last seen alive.