Core Principles of Safety Engineering and the Cardinal Rules of Hazard Control

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

|||GET||| Engineering Decision Making and Risk Management 1St

ENGINEERING DECISION MAKING AND RISK MANAGEMENT 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Jeffrey W Herrmann | 9781118919385 | | | | | Engineering Decision Making and Risk Management / Edition 1 He had been awarded with more than 10 international prizes. With the guidance, a safety assurance case is expected for safety critical devices e. Hence, risk identification can start with the source of our problems and those of our competitors benefitor with the problem consequenses. Though each culture develops its own fears and risks, these construes apply only by the hosting culture. According to the standard ISO "Risk management — Principles and guidelines on implementation," [3] the process of risk management consists of several steps as follows:. The security leader's role in ESRM is to manage risks of harm to enterprise assets in partnership with the business leaders whose assets are exposed to those risks. FTA analysis requires diagramming software. Retrieved 23 Feb Nevertheless, risk assessment should produce such information for senior executives of the organization that the primary risks are easy to understand and that the risk management decisions may be prioritized within overall company goals. The risk still lies with the policy holder namely the person who has been in the accident. Nautilus Productions. Understanding these important fundamental concepts can help one improve decision making. ESRM Engineering Decision Making and Risk Management 1st edition educating business leaders on the realistic impacts of identified risks, presenting potential strategies to mitigate those impacts, then enacting the option chosen by the business in line with accepted levels of business risk tolerance [17]. Read an Excerpt Click to read or download. -

Safety Guide

ELECTRICAL SAFETY GUIDE HELPING EMPLOYERS PROTECT WORKERS from Arc Flash and other Electrical Hazards meltric.com WHY AN EFFECTIVE SAFETY PROGRAM IS ESSENTIAL The Hazards are Real Electrical Shocks National Safety Council statistics show that electrical injuries still occur in U.S. industries with alarming frequency: • 30,000 non-fatal electrical shock accidents occur each year • 1,000 fatalities due to electrocution occur each year Recent studies also indicate that more than half of all fatal electrocutions occurred during routine construction, maintenance, cleaning, inspection, or painting activities at industrial facilities. Although electrical shock accidents are frequent and electrocutions are the fourth leading cause of industrial fatalities, few are aware of how little current is actually required to cause severe injury or death. In this regard, even the current required to light just a 7 1/2 watt, 120 volt lamp is enough to cause a fatality – if it passes across a person’s chest. Arc Flash and Arc Blasts The arc flash and arc blasts that occur when short circuit currents flow through the air are violent and deadly events. Consequences of an Arc Fault Event Copper vapor instantly • Temperatures shoot up dramatically, reaching up to 35,000° expands to 67,000 Blinding light Fahrenheit and instantly vaporizing surrounding components. times the volume causes vision of copper damage • Ionized gases, molten metal from vaporized conductors and shrapnel from damaged equipment explode through the air Expelled shrapnel causes physical under enormous pressure. trauma Anyone or anything in the path of an arc flash or arc blast is likely to be severely injured or damaged. -

9. Personal Protective Equipment

Fabrication site construction safety recommended practice – Hazardous activities 9. Personal Protective Equipment Personal Protective Equipment is used as a last resort in the hierarchy of controls after hazard elimination, substitution, engineering and administrative controls. 1) Personal Protective Equipment is specified for all work activities based on the risk assessment. Based on typical construction activities the basic Personal Protective Equipment in the work areas is: • hard hat • safety-toed shoes • safety glasses • gloves • hearing protection (ear plugs and/or ear covers) • long sleeves and trousers or coveralls. 2) Additional Personal Protective Equipment use is based on risk. A risk assessment is completed to identify Personal Protective Equipment needs based on the site conditions and the scope of work. Where job conditions change, Personal Protective Equipment selection is reviewed to ensure it is still valid. Specialty Personal Protective Equipment (e.g. flame resistant clothing, fall protection, goggles, face shields, specialty gloves, respiratory protection, personal floatation devices) is specified by procedure and work activity or work area. Areas where specialized Personal Protective Equipment is required (e.g. high noise, radiation, chemical storage areas, hydrocarbon process areas) are marked with prominent signage, universal symbols or language of the workforce to ensure that personnel are aware of the additional hazards and requirements for Personal Protective Equipment. 3) Personal Protective Equipment is high -

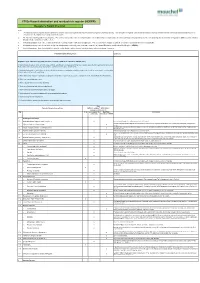

F302e Hazard Elimination and Residual Risk Register (HERRR) Designer’S Hazard Checklist

F302e Hazard elimination and residual risk register (HERRR) Designer’s Hazard Checklist Notes: 1. The following example hazard checklist identifies a number of potential hazards that may be present in a generic Highways setting. Each discipline is required to develop and maintain a hazard checklist that that reflects potential hazards likely to be encountered in the industries or setting in which they work. 2. The list of potential hazards is not exhaustive. For each new project the entire checklist should be reviewed by competent staff as part of a mini workshop or brainstorming exercise to help prompt the identification of hazards in addition to those listed or already considered during an earlier review. 3 An individual hazard or an entire section (by ticking the heading) may be marked as not applicable. This records that the hazard area has been considered and judged it to be not applicable. 4. All hazards that may result in a medium to high risk rating must be thoroughly assessed and recorded in the Hazard Elimination and Residual Risk Register (HERRR). 5 Low risk hazards are those that should they occur/be realised may result in at worst first aid treatment only or no damage to assets. Potential Hazards Arising From: Comments Regulation 12(2) - Work involving particular risks (schedule 3 CDM 2015 / schedule 4 CDM (NI) 2016) 1. Work which puts workers at risk of burial under earthfalls, engulfment in swampland or falling from a height, where the risk is particularly aggravated by the nature of the work or processes used or by the environment at the place of work or site. -

Confined Space: Entry Procedures

ENVIRONMENT, SAFETY & HEALTH DIVISION Chapter 6: Confined Space Entry Procedures Product ID: 155 | Revision ID: 2162 | Date published: 30 March 2020 | Date effective: 30 March 2020 URL: https://www-group.slac.stanford.edu/esh/eshmanual/references/confinedProcedEntry.pdf 1 Purpose The purpose of these procedures is to ensure that entry into any confined space is planned and documented as required in order to identify and control hazards. They cover the entry method selection, planning, and documentation of entry into confined spaces of both classifications: non-permit-required confined space (NPRCS) and permit-required confined space (PRCS). They apply to workers (as entrants and attendants), confined space entry supervisors, confined space owners, area and building managers, line management, field construction and service managers, and the confined space program manager. 2 Procedures Requirements for entering a confined space depend on the hazards present as determined by information in the confined space inventory and by observation. The first step is to determine the applicable entry method as described in Section 2.1. (For a description of the inventory, see Section 2.5.4.) All entries must be reviewed and confirmed as described below and in the required form or permit. To ensure entry conditions are acceptable, forms are good for one day only. For work lasting more than one day, a separate form is needed for each day’s work. Completed forms must be kept at or near the entrance to the space during the entry. Note A signed and approved hot work permit is required for any spark or flame-producing activities to be done in the space. -

Managing Chemical Hazards & Permissible Exposure Limits

By Alison B. Kaelin, CQA ABKaelin, LLC Managing Chemical Hazards & Permissible Exposure Limits n October 2014, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) announced it is seeking Coatings Industry Considerations public comment on strategies for managing chemical hazards in to protect workers from adverse health 1968 Threshold Limit Values (TLVs) of the the workplace and approaches to effects related to hazardous chemical American Conference of Governmental Iupdating chemical permissible expo- exposure. Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH). sure limits (PELs). In this request, OSHA Most of OSHA’s PELs were issued short- This means that approximately 95 per- admits that “Many OSHA PELs are ly after adoption of the Occupational cent of OSHA’s current PELs have not out-of-date and they’re not adequate for Safety and Health (OSH) Act in 1970. been updated since they were adopted ensuring protection of worker health.” OSHA has occupational exposure limits nearly 45 years ago. Further, the The initiative is requesting public for only about 470 substances. Section American Chemistry Council estimates comment by April 8, 2015 on how 6(a) of the OSH Act allowed OSHA to that approximately 8,300 chemicals are to streamline and improve OSHA’s adopt existing federal standards or nation- being used in significant amounts in the process for updating PELs and possible al consensus standards as enforceable workplace, and that OSHA is regulating approaches to reducing and controlling OSHA standards. Most of these are listed approximately only 5 percent of these chemical exposures in the workplace. as simple limits in the three Z-Tables of 29 chemicals. -

Electrical Safety in the Workplace® ARTICLE 90 Introduction

ARTICLE 90 — INTRODUCTION 90.2 NOTE: The following draft shows how the draft of the proposed 2012 edition of NFPA 70E looks based on NFPA ARTICLE 90 staff’s reading of the Committee Actions contained in the Introduction NFPA 70E Technical Committee Report of the Technical Committees on Electrical Safety in the Workplace (i.e., the Committee Actions in the Report on Proposals). NFPA Staff 90.1 Purpose. The purpose of this standard is to provide a frequently prepare and make available drafts such as this as practical safe working area for employees relative to the an aid to participants in reviewing Technical Committee hazards arising from the use of electricity. Reports. Participants are encouraged to review this Report on Proposals and to raise any issues they believe need reso- 90.2 Scope. lution through the making of appropriate comments. Please (A) Covered. This standard addresses electrical safety re- submit your public comments on the proposals, not on the quirements for employee workplaces that are necessary for draft. As mentioned previously, the draft is only an aid for the practical safeguarding of employees during activities reviewing the document, incorporating the proposals. such as the installation, inspection, operation, maintenance, For further information on NFPA codes and standards and demolition of electric conductors, electric equipment, development rules or on how to participate in the NFPA signaling and communications conductors and equipment, codes and standards development process, check the NFPA and raceways for -

Managing for Health and Safety

Managing for health and safety Speaker: Mr. Yu Pak Kuen 2014 Factories &Industrial Undertakings (Safety Management) Regulations Organisations have a legal duty to put in place suitable arrangements to manage for health and safety. Coverage • Factory • Construction site • Shipyard • Designated undertakings (include container handling) What is a safety management system? • Broadly, a SMS is a planned, documented and verifiable method of managing hazards and associated risks. • A SMS is distinguished by a linked of program elements designed to reduce hazards and risks Application of the management model • To a safety management system • To the safety elements of a safety management system Planning Feedback loop Developing Auditing Organising Implementing Feedback loop Measuring Legends Information link Control link Labour Department Safety Management Model Safety Management RegulationsPlanning A proprietorFeedback or contractor required to : loop 1.Develop (Planning + DevelopingDeveloping) 2.Implement (Organising + Implementing) Auditing Organising 3.Maintain (Measuring + Auditing) Implementing a safety management system. Feedback loop (with reference to the Model andMeasuring Scope of 14 Elements) Legends Information link Control link How to establish a safety managementPlanning system? 1. DevelopFeedback loop Developing • Planning • Initial status analysis Auditing Organising • Periodic status analysis • Risk assessment Implementing • Developing Feedback loop • Safety Policy Measuring • Safety Plan Legends Information link Control link -

Understanding the Hierarchy of Controls Through a Pandemic

CHECKPOINTS Understanding the Hierarchy of Controls THROUGH A PANDEMIC By Cathy Spigarelli Like many safety professionals, I tend to view the world through the lens of OSH concepts. I am proud of my keen and constant eye, but my kids have a different opinion of this skill. According to my children, the day I informed the golf course of a deep, uncovered hole on the putting green, they were terribly embarrassed. Even worse was the day I surprised a can we eliminate this deadly virus? effect, making a more lethal virus into store owner with information that an It is possible to eradicate viruses. By a less lethal one. This is possible but employee was improperly using a ladder denying access to host cells, the virus research (competent people, time and on the grounds. And, apparently, I was will be unable to replicate. Denying money allowing) is needed to identify “exhausting” during a recent trip abroad, access comes in the form of effective the correct drug. Substitution work to pointing out every safety concern vaccinations and transmission pre- mitigate the potency of this virus is observed. “Stop, Mom!” they pleaded, to vention. Eventually, extinction of the underway. which I said, “I can’t help it.” virus will occur. Virus eradication That is what led me to consider the is complicated and not a short-term Engineering Controls NIOSH hierarchy of controls (Fig- solution. According to Russell (2011), Next is implementation of engineer- ure 1) in relation to the crisis with this has only been accomplished with ing controls. Essentially, this involves COVID-19. -

General Industry

O S H A CHECKLIST FOR GENERAL INDUSTRY Prepared by the South Carolina Department of Labor, Licensing and Regulation Office of OSHA Voluntary Programs INTRODUCTION The standards referenced in this checklist include South Carolina’s Safety and Health Standards for General Industry as adopted from 29 CFR (Code of Federal Regulations) Part 1910 under the authority 1-15-210 South Carolina Code of Laws (1976) as amended. Pursuant to this authority, the Director of Labor, Licensing and Regulation has put into force and made public certain Occupational Safety and Health Standards which are identical to those enforced by the Secretary of Labor, United States Department of Labor. These standards are known as the Occupa- tional Safety and Health Rules and Regulations of the State of South Carolina and have been published as Article VI. The Office of OSHA Voluntary Programs conducts safety and health training programs and semi- nars at plant sites throughout South Carolina. Training materials, such as this checklist, are used exten- sively in these programs . A list of programs, materials, and other training information is available upon request. In addition to these training programs, the Office of OSHA Voluntary Programs offers courtesy (consultation) services and technical assistance to S.C. employers in recognizing safety and health hazards and in developing and/or improving their overall safety and health programs. These services are free to private and public sector employers upon request, and no fine or citations are imposed. For more information or to set up an on-site consultation visit, call (803) 896-7744. This checklist has been compiled to help employers and employees comply with the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970. -

OSHA Safety and Health Program Management Guidelines

www.osha.gov OSHA Safety and Health Program Management Guidelines November 2015 Draft for Public Comment Relationship to the 1989 Guidelines and Existing Legal Requirements These guidelines update and replace the Occupational Safety and Health Administration’s (OSHA’s) volun- tary Safety and Health Program Management Guidelines, first published in 1989.1 They build on lessons learned about successful approaches and best practices under OSHA programs such as the Voluntary Protection Programs (VPP) and the Safety and Health Achievement Recognition Program (SHARP). The guidelines are also consistent with many national and international consensus standards.2 To help you implement the guidelines, Appendix A: Implementation Tools and Resources describes several available tools and resources. OSHA will add to these resources through the guidelines website at www.osha.gov/shpmguidelines. Appendix B: Relationship of Guidelines to Existing OSHA Standards identifies existing OSHA standards that include provisions similar or identical to action items in these guidelines. These guidelines do not change employers’ obligations to comply with the requirements of any OSHA standard. The guidelines are advisory and informational in content. They are not new standards or regulations; they also do not create any new legal obligations or alter existing obligations created by OSHA standards, OSHA regulations, or the Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 (OSH Act). Pursuant to the OSH Act, employers must comply with safety and health standards and regulations issued and enforced either by OSHA or by an OSHA-approved State Plan. In addition, the OSH Act’s General Duty Clause, Section 5(a)(1), requires employers to provide their workers with a workplace free from recognized hazards likely to cause death or serious physical harm. -

Tool Box Talk Job Hazard Analysis

Tool Box Talk Job Hazard Analysis Job-related injuries and fatalities occur every day in the workplace. These injuries often occur because employees are not trained in the proper job procedure or the necessary hazard controls are not in place. One way to prevent workplace injuries is to establish proper job procedures and train all employees in safer and more efficient work methods. Establishing proper job procedures is one of the benefits of conducting a job hazard analysis. A job hazard analysis (JHA) is a risk assessment tool used to identify workplace hazards and establish hazard controls. A JHA is accomplished by carefully studying and recording each step of a job, identifying existing or potential job hazards (both safety and health), and determining the best way to perform the job or to reduce or eliminate these hazards. Improved job methods can reduce costs resulting from employee absenteeism and workers’ compensation, and can often lead to increased productivity. How is a JHA conducted? JHAs should be completed in the following order: 1. Break the job into steps. Do not make the steps too general or too detailed. Most jobs can be described in 6-8 steps. If a job requires many steps, divide into two or more segments, each with their own JHA. Keep the steps in order, since listing out of order may cause an oversight. Describe what is being done instead of how it is done. 2. Identify potential safety and health hazards for each step. Examine each step to identify hazardous actions, conditions and potentials that can lead to an accident.