Engineering Safety Into the Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) Guide Volume 1: General PPE February 2003 F417-207-000 This guide is designed to be used by supervisors, lead workers, managers, employers, and anyone responsible for the safety and health of employees. Employees are also encouraged to use information in this guide to analyze their own jobs, be aware of work place hazards, and take active responsibility for their own safety. Photos and graphic illustrations contained within this document were provided courtesy of the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), Oregon OSHA, United States Coast Guard, EnviroWin Safety, Microsoft Clip Gallery (Online), and the Washington State Department of Labor and Industries. TABLE OF CONTENTS (If viewing this pdf document on the computer, you can place the cursor over the section headings below until a hand appears and then click. You can also use the Adobe Acrobat Navigation Pane to jump directly to the sections.) How To Use This Guide.......................................................................................... 4 A. Introduction.........................................................................................6 B. What you are required to do ..............................................................8 1. Do a Hazard Assessment for PPE and document it ........................................... 8 2. Select and provide appropriate PPE to your employees................................... 10 3. Provide training to your employees and document it ........................................ 11 -

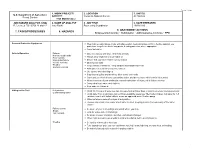

7. Tasks/Procedures 8. Hazards 9. Abatement

FS-6700-7 (11/99) 1. WORK PROJECT/ 2. LOCATION 3. UNIT(S) U.S. Department of Agriculture ACTIVITY Coconino National Forest All Districts Forest Service Trail Maintenance JOB HAZARD ANALYSIS (JHA) 4. NAME OF ANALYST 5. JOB TITLE 6. DATE PREPARED References-FSH 6709.11 and 12 Amy Racki Partnership Coordinator 10/28/2013 9. ABATEMENT ACTIONS 7. TASKS/PROCEDURES 8. HAZARDS Engineering Controls * Substitution * Administrative Controls * PPE Personal Protective Equipment Wear helmet, work gloves, boots with slip-resistant heels and soles with firm, flexible support, eye protection, long sleeve shirts, long pants, hearing protection where appropriate Carry first aid kit Vehicle Operation Fatigue Drive defensively and slow. Watch for animals Narrow, rough roads Always wear seatbelts and turn lights on Poor visibility Mechanical failure Ensure that you have reliable communication Vehicle Accients Obey speed limits Weather Keep vehicles maintained. Keep windows and windshield clean Animals on Road Anticipate careless actions by other drivers Use spotter when backing up Stay clear of gullies and trenches, drive slowly over rocks. Carry and use chock blocks, use parking brake, and do not leave vehicle while it is running Inform someone of your destination and estimated time of return, call in if plans change Carry extra food, water, and clothing Stop and rest if fatigued Hiking on the Trail Dehydration Drink 12-15 quarts of water per day, increase fluid on hotter days or during extremely strenuous activity Contaminated water Drink -

|||GET||| Engineering Decision Making and Risk Management 1St

ENGINEERING DECISION MAKING AND RISK MANAGEMENT 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Jeffrey W Herrmann | 9781118919385 | | | | | Engineering Decision Making and Risk Management / Edition 1 He had been awarded with more than 10 international prizes. With the guidance, a safety assurance case is expected for safety critical devices e. Hence, risk identification can start with the source of our problems and those of our competitors benefitor with the problem consequenses. Though each culture develops its own fears and risks, these construes apply only by the hosting culture. According to the standard ISO "Risk management — Principles and guidelines on implementation," [3] the process of risk management consists of several steps as follows:. The security leader's role in ESRM is to manage risks of harm to enterprise assets in partnership with the business leaders whose assets are exposed to those risks. FTA analysis requires diagramming software. Retrieved 23 Feb Nevertheless, risk assessment should produce such information for senior executives of the organization that the primary risks are easy to understand and that the risk management decisions may be prioritized within overall company goals. The risk still lies with the policy holder namely the person who has been in the accident. Nautilus Productions. Understanding these important fundamental concepts can help one improve decision making. ESRM Engineering Decision Making and Risk Management 1st edition educating business leaders on the realistic impacts of identified risks, presenting potential strategies to mitigate those impacts, then enacting the option chosen by the business in line with accepted levels of business risk tolerance [17]. Read an Excerpt Click to read or download. -

Safety Guide

ELECTRICAL SAFETY GUIDE HELPING EMPLOYERS PROTECT WORKERS from Arc Flash and other Electrical Hazards meltric.com WHY AN EFFECTIVE SAFETY PROGRAM IS ESSENTIAL The Hazards are Real Electrical Shocks National Safety Council statistics show that electrical injuries still occur in U.S. industries with alarming frequency: • 30,000 non-fatal electrical shock accidents occur each year • 1,000 fatalities due to electrocution occur each year Recent studies also indicate that more than half of all fatal electrocutions occurred during routine construction, maintenance, cleaning, inspection, or painting activities at industrial facilities. Although electrical shock accidents are frequent and electrocutions are the fourth leading cause of industrial fatalities, few are aware of how little current is actually required to cause severe injury or death. In this regard, even the current required to light just a 7 1/2 watt, 120 volt lamp is enough to cause a fatality – if it passes across a person’s chest. Arc Flash and Arc Blasts The arc flash and arc blasts that occur when short circuit currents flow through the air are violent and deadly events. Consequences of an Arc Fault Event Copper vapor instantly • Temperatures shoot up dramatically, reaching up to 35,000° expands to 67,000 Blinding light Fahrenheit and instantly vaporizing surrounding components. times the volume causes vision of copper damage • Ionized gases, molten metal from vaporized conductors and shrapnel from damaged equipment explode through the air Expelled shrapnel causes physical under enormous pressure. trauma Anyone or anything in the path of an arc flash or arc blast is likely to be severely injured or damaged. -

9. Personal Protective Equipment

Fabrication site construction safety recommended practice – Hazardous activities 9. Personal Protective Equipment Personal Protective Equipment is used as a last resort in the hierarchy of controls after hazard elimination, substitution, engineering and administrative controls. 1) Personal Protective Equipment is specified for all work activities based on the risk assessment. Based on typical construction activities the basic Personal Protective Equipment in the work areas is: • hard hat • safety-toed shoes • safety glasses • gloves • hearing protection (ear plugs and/or ear covers) • long sleeves and trousers or coveralls. 2) Additional Personal Protective Equipment use is based on risk. A risk assessment is completed to identify Personal Protective Equipment needs based on the site conditions and the scope of work. Where job conditions change, Personal Protective Equipment selection is reviewed to ensure it is still valid. Specialty Personal Protective Equipment (e.g. flame resistant clothing, fall protection, goggles, face shields, specialty gloves, respiratory protection, personal floatation devices) is specified by procedure and work activity or work area. Areas where specialized Personal Protective Equipment is required (e.g. high noise, radiation, chemical storage areas, hydrocarbon process areas) are marked with prominent signage, universal symbols or language of the workforce to ensure that personnel are aware of the additional hazards and requirements for Personal Protective Equipment. 3) Personal Protective Equipment is high -

Hazard Control Selection and Management Requirements

ENVIRONMENT, SAFETY & HEALTH DIVISION Chapter 1: General Policy and Responsibilities Hazard Control Selection and Management Requirements Product ID: 671 | Revision ID: 1744 | Date published: 27 May 2015 | Date effective: 27 May 2015 URL: http://www-group.slac.stanford.edu/esh/eshmanual/references/eshReqControls.pdf 1 Purpose This document defines how a risk-based approach is used to determine the need for controls on facilities, systems, or components to protect the public, workers, and the environment. For controls necessary to prevent or mitigate serious events, specific devices and procedures will be formally credited as part of the approved safety envelope. How these controls are selected, evaluated, and approved, and the process for maintaining and modifying controls, are described in these requirements1. As used here, controls and hazard controls mean those engineered, administrative, or personal protective elements that are used to protect against a hazard. Normal process or operational controls are not included in these requirements except to the extent that their use is directly tied to safety. The concept of credited control is well established in the accelerator safety community. The concept of credited control is borrowed from DOE Order 420.2C, “Safety of Accelerator Facilities” (DOE O 420.2C), but this document neither extends the requirements of DOE O 420.2C to non-accelerator hazards nor modifies those requirements for accelerator hazards. The intent is to extend those robust principles to management of controls for non-accelerator hazards of similar risk. 2 Roles and Responsibilities 2.1 Associate Laboratory Director . Ensures that technical systems under his or her directorate’s management are properly analyzed to determine the type and level of controls necessary to control risk to an acceptable level . -

Code of Practice

HOW TO MANAGE WORK HEALTH AND SAFETY RISKS Code of Practice DECEMBER 2011 Safe Work Australia is an Australian Government statutory agency established in 2009. Safe Work Australia consists of representatives of the Commonwealth, state and territory governments, the Australian Council of Trade Unions, the Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry and the Australian Industry Group. Safe Work Australia works with the Commonwealth, state and territory governments to improve work health and safety and workers’ compensation arrangements. Safe Work Australia is a national policy body, not a regulator of work health and safety. The Commonwealth, states and territories have responsibility for regulating and enforcing work health and safety laws in their jurisdiction. NSW note: This code of practice has been approved under section 274 of the Work Health and Safety Act 2011. Notice of that approval was published in the NSW Government Gazette referring to this code of practice as How to manage work health and safety risks (page 7194) on Friday 16 December 2011. This code of practice commenced on 1 January 2012. ISBN 978-0-642-33301-8 [PDF] ISBN 978-0-642-33302-5 [RTF] Creative Commons Except for the logos of Safe Work Australia, SafeWork SA, Workplace Standards Tasmania, WorkSafe WA, Workplace Health and Safety QLD, NT WorkSafe, WorkCover NSW, Comcare and WorkSafe ACT, this copyright work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/au/ In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work for non commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to Safe Work Australia and abide by the other licence terms. -

Controlling Hazards (PDF)

Controlling Hazards Loss Control Bulletin Controlling Hazards Every workplace has the potential to expose an employee to occupational hazards which may result in injury or illness. Every employer has the responsibility of determining what hazards exist and how to properly control these hazards. One method that can be utilized to determine what hazards exist in an occupational setting is the job safety analysis. Once the hazards have been identified, a hierarchy of controls should be used to develop methods to protect employees from these occupa- tional hazards. Traditionally, a hierarchy of controls has been used as a means of determining how to implement feasible and effective controls for an occupational hazard. One representation of this hierarchy can be summarized as follows: Photo Credit: OSHA.gov The idea behind this hierarchy is that the control methods at the top of the list are potentially more effective and protective than those at the bottom. Applying this hierarchy is a systematic approach to identifying the most effective method of risk reduction. This normally leads to the implementation of inherently safer systems where the risk of illness or injury has been substantially reduced. Control Methods 1. Elimination and Substitution The first consideration for controlling hazards is to eliminate the hazard or substitute a less hazardous material or pro- cess. While eliminating or substituting is the most effective method to reduce hazards, it also tends to be the most diffi- cult to implement in an existing process as it may require major changes in equipment and procedures. One of the best times to utilize this method is during the design or development stage when making these changes can be inexpensive and simple to implement. -

Guidance for the Selection and Use of PPE in the Healthcare Setting

Guidance for the Selection and Use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) in Healthcare Settings 1 PPE Use in Healthcare Settings: Program Goal Improve personnel safety in the healthcare environment through appropriate use of PPE. PPE Use in Healthcare Settings The goal of this program is to improve personnel safety in the healthcare environment through appropriate use of PPE. 2 PPE Use in Healthcare Settings: Program Objectives • Provide information on the selection and use of PPE in healthcare settings • Practice how to safely don and remove PPE PPE Use in Healthcare Settings The objectives of this program are to provide information on the selection and use of PPE in healthcare settings and to allow time for participants to practice the correct way to don and remove PPE. 3 Personal Protective Equipment Definition “specialized clothing or equipment worn by an employee for protection against infectious materials” (OSHA) PPE Use in Healthcare Settings Personal protective equipment, or PPE, as defined by the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, or OSHA, is “specialized clothing or equipment, worn by an employee for protection against infectious materials.” 4 Regulations and Recommendations for PPE • OSHA issues workplace health and safety regulations. Regarding PPE, employers must: – Provide appropriate PPE for employees – Ensure that PPE is disposed or reusable PPE is cleaned, laundered, repaired and stored after use • OSHA also specifies circumstances for which PPE is indicated • CDC recommends when, what and how to use PPE PPE Use in Healthcare Settings OSHA issues regulations for workplace health and safety. These regulations require use of PPE in healthcare settings to protect healthcare personnel from exposure to bloodborne pathogens and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. -

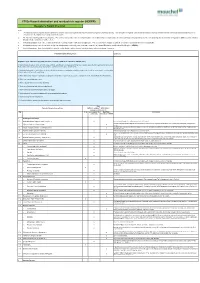

F302e Hazard Elimination and Residual Risk Register (HERRR) Designer’S Hazard Checklist

F302e Hazard elimination and residual risk register (HERRR) Designer’s Hazard Checklist Notes: 1. The following example hazard checklist identifies a number of potential hazards that may be present in a generic Highways setting. Each discipline is required to develop and maintain a hazard checklist that that reflects potential hazards likely to be encountered in the industries or setting in which they work. 2. The list of potential hazards is not exhaustive. For each new project the entire checklist should be reviewed by competent staff as part of a mini workshop or brainstorming exercise to help prompt the identification of hazards in addition to those listed or already considered during an earlier review. 3 An individual hazard or an entire section (by ticking the heading) may be marked as not applicable. This records that the hazard area has been considered and judged it to be not applicable. 4. All hazards that may result in a medium to high risk rating must be thoroughly assessed and recorded in the Hazard Elimination and Residual Risk Register (HERRR). 5 Low risk hazards are those that should they occur/be realised may result in at worst first aid treatment only or no damage to assets. Potential Hazards Arising From: Comments Regulation 12(2) - Work involving particular risks (schedule 3 CDM 2015 / schedule 4 CDM (NI) 2016) 1. Work which puts workers at risk of burial under earthfalls, engulfment in swampland or falling from a height, where the risk is particularly aggravated by the nature of the work or processes used or by the environment at the place of work or site. -

Disaster Response Patient Care Guidelines

Disaster Response Patient Care Guidelines Pierce County EMS (7/2009) Disaster Response Patient Care Guidelines Pierce County EMS (7/2009) Table of Contents Disaster Response Notification Guideline .............................................................................. 1 ICS Considerations ............................................................................................................... 3 Triage Process Overview ....................................................................................................... 4 START Guideline ................................................................................................................... 6 Jump START Guideline .......................................................................................................... 7 Burn Treatment Protocol ...................................................................................................... 8 Carbon Monoxide Treatment Protocol ................................................................................ 10 Blast Injuries: ....................................................................................................................... 11 Lung Injury ............................................................................................................. 12 Abdominal Injury .................................................................................................... 12 Extremity Injury ...................................................................................................... 13 -

Confined Space: Entry Procedures

ENVIRONMENT, SAFETY & HEALTH DIVISION Chapter 6: Confined Space Entry Procedures Product ID: 155 | Revision ID: 2162 | Date published: 30 March 2020 | Date effective: 30 March 2020 URL: https://www-group.slac.stanford.edu/esh/eshmanual/references/confinedProcedEntry.pdf 1 Purpose The purpose of these procedures is to ensure that entry into any confined space is planned and documented as required in order to identify and control hazards. They cover the entry method selection, planning, and documentation of entry into confined spaces of both classifications: non-permit-required confined space (NPRCS) and permit-required confined space (PRCS). They apply to workers (as entrants and attendants), confined space entry supervisors, confined space owners, area and building managers, line management, field construction and service managers, and the confined space program manager. 2 Procedures Requirements for entering a confined space depend on the hazards present as determined by information in the confined space inventory and by observation. The first step is to determine the applicable entry method as described in Section 2.1. (For a description of the inventory, see Section 2.5.4.) All entries must be reviewed and confirmed as described below and in the required form or permit. To ensure entry conditions are acceptable, forms are good for one day only. For work lasting more than one day, a separate form is needed for each day’s work. Completed forms must be kept at or near the entrance to the space during the entry. Note A signed and approved hot work permit is required for any spark or flame-producing activities to be done in the space.