Thomas Merton and Walker Percy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My Town: Writers on American Cities

MY TOW N WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES MY TOWN WRITERS ON AMERICAN CITIES CONTENTS INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud .......................................... 2 THE POETRY OF BRIDGES by David Bottoms ........................... 7 GOOD OLD BALTIMORE by Jonathan Yardley .......................... 13 GHOSTS by Carlo Rotella ...................................................... 19 CHICAGO AQUAMARINE by Stuart Dybek ............................. 25 HOUSTON: EXPERIMENTAL CITY by Fritz Lanham .................. 31 DREAMLAND by Jonathan Kellerman ...................................... 37 SLEEPWALKING IN MEMPHIS by Steve Stern ......................... 45 MIAMI, HOME AT LAST by Edna Buchanan ............................ 51 SEEING NEW ORLEANS by Richard Ford and Kristina Ford ......... 59 SON OF BROOKLYN by Pete Hamill ....................................... 65 IN SEATTLE, A NORTHWEST PASSAGE by Charles Johnson ..... 73 A WRITER’S CAPITAL by Thomas Mallon ................................ 79 INTRODUCTION by Claire Messud ore than three-quarters of Americans live in cities. In our globalized era, it is tempting to imagine that urban experiences have a quality of sameness: skyscrapers, subways and chain stores; a density of bricks and humanity; a sense of urgency and striving. The essays in Mthis collection make clear how wrong that assumption would be: from the dreamland of Jonathan Kellerman’s Los Angeles to the vibrant awakening of Edna Buchanan’s Miami; from the mid-century tenements of Pete Hamill’s beloved Brooklyn to the haunted viaducts of Stuart Dybek’s Pilsen neighborhood in Chicago; from the natural beauty and human diversity of Charles Johnson’s Seattle to the past and present myths of Richard Ford’s New Orleans, these reminiscences and musings conjure for us the richness and strangeness of any individual’s urban life, the way that our Claire Messud is the author of three imaginations and identities and literary histories are intertwined in a novels and a book of novellas. -

Bakalářská Práce 2012

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by DSpace at University of West Bohemia Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce 2016 Martina Veverková Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Bakalářská práce THE ROCK BAND QUEEN AS A FORMATIVE FORCE Martina Veverková Plzeň 2016 Západočeská univerzita v Plzni Fakulta filozofická Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Studijní program Filologie Studijní obor Cizí jazyky pro komerční praxi Kombinace angličtina – němčina Bakalářská práce THE ROCK BAND QUEEN AS A FORMATIVE FORCE Vedoucí práce: Mgr. et Mgr. Jana Kašparová Katedra anglického jazyka a literatury Fakulta filozofická Západočeské univerzity v Plzni Plzeň 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem práci zpracovala samostatně a použila jen uvedených pramenů a literatury. Plzeň, duben 2016 ……………………… I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. et Mgr. Jana Kašparová for her advice which have helped me to complete this thesis I would also like to thank my friend David Růžička for his support and help. Table of content 1 Introduction ...................................................................... 1 2 The Evolution of Queen ................................................... 2 2.1 Band Members ............................................................................. 3 2.1.1 Brian Harold May .................................................................... 3 2.1.2 Roger Meddows Taylor .......................................................... 4 2.1.3 Freddie Mercury -

Or, the Last Confederate Cruiser

THE MAGAZINE OF HISTORY WITH NOTES AND QUERIES fxira Number No. 12 THE SHENANDOAH; OR THE LAST CONFED ERATE CRUISER Cornelius E. Hunt, One of her Officers WILLIAM ABBATT 141 EAST 25TH STREET, . NEW YORK 1910 COPYRIGHT, 1910, BY WILLIAM ABBATT THE OLD RIP OF THE SHENANDOAH. CAPTAIN WADDEW, (as Kip Van Winkle). "Law! Mr. Pilot, you don t say so! The war in America over these Eight Months? Dear ! dear ! who d ever a thought it !" Harper s Weekly, Dec. 9, 1865. v THE SHENANDOAH, THE LAST CONFEDERATE CRUISER BY CORNELIUS E. HUNT (ONE OF HER OFFICERS). NEW YORK G. W. CARLETON& CO. LONDON: S. LOW, SON, & CO. 1867 NEW YORK Reprinted WILLIAM ABBATT 1910 (Being Extra No. 12 of THE MAGAZINE OF HISTORY WITH NOTES AND QUERIES.) Facsimile of the original THE SHENANDOAH; OR THE LAST CONFEDERATE CRUISER, CORNELIUS E. HUNT, (ONE OF BEE OFTICEBS). NEW YORK: C. W. CARLETON, & CO. PUBLISHERS. LONDON : S. LOW, SON, & CO. MDCCCLXYU. EDITOR S PREFACE The cruise of the Skenandoah is one of the scarce items of its day. Only two copies have come to our notice in seven years, and " as the stories of the Alabama-Kearsage, and "Captain Roberts Never Caught have proven among the most popular of our " Extras," no doubt this one will be almost or quite as interesting to our readers; particularly as it has never before been reprinted since its original appearance in 1867. " Its author, a Virginian, is described as an acting-master s mate," in Scharf s History of the Confederate Navy, but we have no further information of him. -

AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 Songs, 2.8 Days, 5.36 GB

Page 1 of 28 **AD GUITAR INSTRUCTION** 943 songs, 2.8 days, 5.36 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 I Am Loved 3:27 The Golden Rule Above the Golden State 2 Highway to Hell TUNED 3:32 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 3 Dirty Deeds Tuned 4:16 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 4 TNT Tuned 3:39 AD Tuned Files and Edits AC/DC 5 Back in Black 4:20 Back in Black AC/DC 6 Back in Black Too Slow 6:40 Back in Black AC/DC 7 Hells Bells 5:16 Back in Black AC/DC 8 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 4:16 Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap AC/DC 9 It's A Long Way To The Top ( If You… 5:15 High Voltage AC/DC 10 Who Made Who 3:27 Who Made Who AC/DC 11 You Shook Me All Night Long 3:32 AC/DC 12 Thunderstruck 4:52 AC/DC 13 TNT 3:38 AC/DC 14 Highway To Hell 3:30 AC/DC 15 For Those About To Rock (We Sal… 5:46 AC/DC 16 Rock n' Roll Ain't Noise Pollution 4:13 AC/DC 17 Blow Me Away in D 3:27 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 18 F.S.O.S. in D 2:41 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 19 Here Comes The Sun Tuned and… 4:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 20 Liar in E 3:12 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 21 LifeInTheFastLaneTuned 4:45 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 22 Love Like Winter E 2:48 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 23 Make Damn Sure in E 3:34 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 24 No More Sorrow in D 3:44 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 25 No Reason in E 3:07 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 26 The River in E 3:18 AD Tuned Files and Edits AD Tuned Files 27 Dream On 4:27 Aerosmith's Greatest Hits Aerosmith 28 Sweet Emotion -

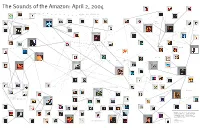

View the Poster

M.A.D.E. Split Personality Hood Hop Memphis Bleek Cassidy J-Kwon The Sounds of the Amazon: April 2, 2004 December 16, 2003 March 16, 2004 March 30, 2003 Room on Fire The Black Album The Strokes Jay-Z October 28, 2003 November 14, 2003 Chutes Too Narrow A Rush of Blood to the Head Kamikaze The Shins Coldplay Twista October 21, 2003 August 27, 2002 ADULT ALTERNATIVE November 14, 2003 Audioslave Away from the Sun My Private Nation Chariot Waiting for My Rocket to Come Speakerboxxx/The Love Below Cee-Lo Green is the Soul Machine Fallen Audioslave 3 Doors Down Train Gavin DeGraw Jason Mraz Outkast Cee-Lo ALTERNATIVE Evanescence #7 November 19, 2002 November 12, 2002 June 3, 2003 July 22, 2003 October 15, 2002 September 23, 2003 March 2, 2004 Bows & Arrows March 4, 2003 Try This Schizophrenic The Walkmen Pink JC Chasez February 3, 2004 H I P November 11, 2003 February 24, 2004 HOP College Dropout Confessions Kaye West #19 Usher #4 Desperate Youth More Than You Think You Are February 10, 2004 March 23, 2004 Franz Ferdinand TV on the Radio Matchbox Twenty Franz Ferdinand #16 March 9, 2004 November 19, 2002 Echoes February 16, 2004 14 Shades of Grey Rapture Staind October 21, 2003 May 20, 2003 POP Hotel Paper Beg for Mercy In The Zone Michelle Branch Songs About Jane G-Unit Britney Spears June 14, 2003 Maroon 5 #11 November 14, 2003 November 18, 2003 June 25, 2002 Remixes Mariah Carey Ocotber 14, 2003 Come Away With Me Norah Jones #8 Meadowlands February 26, 2002 Cheers Let’s Talk About It Wrens Obie Trice Carl Thomas September 9, 2003 September 23, 2003 March 23, 2004 Live in Paris Life for Rent Room for Squares Diana Krall Dido John Mayer October 1, 2002 September 30, 2003 September 18, 2001 Damita Jo Janet Jackson #5 Chicken N Beer Soul Flower March 30, 2004 Ludacris En Vogue October 7, 2003 February 24, 2004 R&B Only You New York City Films About Ghosts Harry Connick, Jr. -

Musica Straniera

MUSICA STRANIERA AUTORE TITOLO UBICAZIONE 4 Hero Two pages Reinterpretations MSS/CD FOU 4 Non Blondes <gruppo musicale>Bigger, better, faster, more! MSS/CD FOU 50 Cent Get Rich Or Die Tryin' MSS/CD FIF AA.VV. Musica coelestis MSS/CD MUS AA.VV. Rotterdam Hardcore MSS/CD ROT AA.VV. Rotterdam Hardcore MSS/CD ROT AA.VV. Febbraio 2001 MSS/CD FEB AA.VV. \Il \\mucchio selvaggio: agosto 2003 MSS/CD MUC AA.VV. \Il \\mucchio selvaggio: aprile 2004 MSS/CD MUC AA.VV. Tendenza Compilation MSS/CD TEN AA.VV. Mixage MSS/CD MIX AA.VV. Hits on five 3 MSS/CD HIT AA.VV. \Il \\mucchio selvaggio: ottobre 2003 MSS/CD MUC AA.VV. \The \\Brain storm selection MSS/CD BRA AA.VV. Solitaire gold MSS/CD SOL AA.VV. Casual love MSS/CD CAS AA.VV. Oh la la la MSS/CD OHL AA.VV. \The \\magic dance compilation MSS/CD MAG AA.VV. Balla la vita, baby vol. 2 MSS/CD BAL AA.VV. \Il \\mucchio selvaggio: dicembre 2003 MSS/CD MUC AA.VV. Harder they come. Soundtrack (The) MSS/CD HAR AA.VV. Cajun Dance Party MSS/CD CAJ AA.VV. \Les \\chansons de Paris MSS/CD CHA AA.VV. \The \\look of love : the Burt Bacharach collection MSS/CD LOO AA.VV. \Le \\canzoni del secolo : 7 MSS/CD CAN AA.VV. Burning heart CD1 MSS/CD BUR AA.VV. \The \\High spirits: spirituals dei neri d'America MSS/CD HIG AA.VV. Dark star rising MSS/CD DAR AA.VV. Merry Christmas from Motown MSS/CD MER AA.VV. -

Album Top 1000 2021

2021 2020 ARTIEST ALBUM JAAR ? 9 Arc%c Monkeys Whatever People Say I Am, That's What I'm Not 2006 ? 12 Editors An end has a start 2007 ? 5 Metallica Metallica (The Black Album) 1991 ? 4 Muse Origin of Symmetry 2001 ? 2 Nirvana Nevermind 1992 ? 7 Oasis (What's the Story) Morning Glory? 1995 ? 1 Pearl Jam Ten 1992 ? 6 Queens Of The Stone Age Songs for the Deaf 2002 ? 3 Radiohead OK Computer 1997 ? 8 Rage Against The Machine Rage Against The Machine 1993 11 10 Green Day Dookie 1995 12 17 R.E.M. Automa%c for the People 1992 13 13 Linkin' Park Hybrid Theory 2001 14 19 Pink floyd Dark side of the moon 1973 15 11 System of a Down Toxicity 2001 16 15 Red Hot Chili Peppers Californica%on 2000 17 18 Smashing Pumpkins Mellon Collie and the Infinite Sadness 1995 18 28 U2 The Joshua Tree 1987 19 23 Rammstein Muaer 2001 20 22 Live Throwing Copper 1995 21 27 The Black Keys El Camino 2012 22 25 Soundgarden Superunknown 1994 23 26 Guns N' Roses Appe%te for Destruc%on 1989 24 20 Muse Black Holes and Revela%ons 2006 25 46 Alanis Morisseae Jagged Liale Pill 1996 26 21 Metallica Master of Puppets 1986 27 34 The Killers Hot Fuss 2004 28 16 Foo Fighters The Colour and the Shape 1997 29 14 Alice in Chains Dirt 1992 30 42 Arc%c Monkeys AM 2014 31 29 Tool Aenima 1996 32 32 Nirvana MTV Unplugged in New York 1994 33 31 Johan Pergola 2001 34 37 Joy Division Unknown Pleasures 1979 35 36 Green Day American idiot 2005 36 58 Arcade Fire Funeral 2005 37 43 Jeff Buckley Grace 1994 38 41 Eddie Vedder Into the Wild 2007 39 54 Audioslave Audioslave 2002 40 35 The Beatles Sgt. -

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 16, 2013 to Sun. September 22, 2013

AXS TV Schedule for Mon. September 16, 2013 to Sun. September 22, 2013 Monday September 16, 2013 4:30 PM ET / 1:30 PM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Nothing But Trailers Dr. Perricone’s Sub D Sometimes the best part of the movie is the preview! So AXS TV presents a half hour of Noth- Cold Plasma Sub-D for a visibly firmer looking chin. Guaranteed by Guthy/Renker or your ing But Trailers. See the best trailers, old and new in AXS TV’s collection. money back. Premiere 6:30 AM ET / 3:30 AM PT 4:45 PM ET / 1:45 PM PT Sheer Cover The Exorcism of Emily Rose Sheer Cover Studio mineral makeup covers flaws beautifully yet feels like wearing nothing at A priest is blamed for the death of a young girl after he performs an exorcism on her but he all. From Guthy-Renker. has horrifying evidence to prove his innocence that not even his lawyer can stand to believe. Starring Laura Linney, Tom Wilkinson, and Cambell Scott. Directed by Scott Derrickson. (2005 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT - PG-13) Dan Rather Reports The Poor Women of Texas - The abortion battle moves to the states. In Texas, new state LIVE! restrictions on abortions have had consequences for the health care of thousands of low 7:00 PM ET / 4:00 PM PT income women, as many clinics that provided services beyond pregnancy termination have AXS Live been forced to close. Also, a radical approach to ending Columbia’s civil war. -

Lost in the Bayou: Language Theory and the Thanatos Syndrome

LOST IN THE BAYOU: LANGUAGE THEORY AND THE THANATOS SYNDROME by GILBERT CALEN VERBIST (Under the Direction of Hugh Ruppersburg) ABSTRACT This thesis investigates the role of Walker Percy‟s theories on language, derived from the writings of Charles Sanders Peirce, in The Thanatos Syndrome. The argument of this thesis is that the language use of individuals affected by heavy sodium poisoning can best be explained in the terms of Percy‟s language theories, even though those theories are not elaborated within the novel itself but in various non-fiction works by the author. One of the central tenets of Percy‟s theory on language is that human language is triadic whereas all other forms of communication (and, in fact, all other phenomena) are dyadic. Percy saw the tendency treat as dyadic the triadic behavior of language to be reductionist and dangerous, which is the commentary inherent in the language use of sodium-affected individuals in The Thanatos Syndrome. INDEX WORDS: The Thanatos Syndrome, Charles Sanders Peirce, language use, triadic, dyadic, semiotics, Lost in the Cosmos LOST IN THE BAYOU: LANGUAGE THEORY AND THE THANATOS SYNDROME by GILBERT CALEN VERBIST BA, Samford University, 2007 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS ATHENS, GEORGIA 2011 © 2011 Gilbert Calen Verbist All Rights Reserved LOST IN THE BAYOU: LANGUAGE USE AND THE THANATOS SYNDROME by GILBERT CALEN VERBIST Major Professor: Hugh Ruppersburg Committee: William Kretzschmar Hubert McAlexander Electronic Version Approved: Maureen Grasso Dean of the Graduate School The University of Georgia May 2011 iv DEDICATION To my mother and father, who never forced me to major in something marketable. -

THE HUMANITY STRAIN: DIAGNOSING the SELF in WALKER PERCY's FICTION by HILLARY MCDONALD a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Facu

THE HUMANITY STRAIN: DIAGNOSING THE SELF IN WALKER PERCY’S FICTION BY HILLARY MCDONALD A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of WAKE FOREST UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS English May 2014 Winston-Salem, North Carolina Approved By: James Hans, Ph.D., Advisor Eric Wilson, Ph.D., Chair Barry Maine, Ph.D ii DEDICATION This work of diagnostic scholarship is dedicated to my father Hal McDonald, a fellow Percyan wayfarer, and my mother Nancy McDonald for her constant love and support iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS If I have learned one thing in my experience, it is that a writer, though solitary by nature, never truly works alone. All authors are indebted to those who came before them, as well as the mentors, family, and friends who provided guidance and support during the creative process. Therefore, as I complete this capstone of my academic career at Wake Forest, I would be remiss if I did not acknowledge those who made this thesis possible. Thank you to my advisor, James Hans, who willingly put up with me for both my undergraduate and graduate years, and had much more confidence in my writing ability than I did during that time. Thank you to Eric Wilson, who showed me that it is possible to cross literary boundaries by writing non-fiction that is creative, as well as studying William Blake and David Lynch in the same class. Thank you to my loving family, who patiently talked me through my moments of self-doubt and uncertainty, and thank you to my friends, who were always willing to provide a welcome escape from the “same dull round” of writing. -

A Political Companion to Walker Percy

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Kentucky University of Kentucky UKnowledge Literature in English, North America English Language and Literature 7-19-2013 A Political Companion to Walker Percy Peter Augustine Lawler Berry College Brian A. Smith Montclair State University Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Lawler, Peter Augustine and Smith, Brian A., "A Political Companion to Walker Percy" (2013). Literature in English, North America. 75. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature_north_america/75 A Political Companion to Walker Percy A Political Companion to Walker Percy Edited by PETER AUGUSTINE LAWLER and BRIAN A. SMITH Copyright © 2013 by The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 17 16 15 14 13 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A political companion to Walker Percy / edited by Peter Augustine Lawler and Brian A. -

Popular Culture and Intellectual Identity in the Work of Walker Percy Jordan J

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2006 "The Nature of the Search": Popular Culture and Intellectual Identity in the Work of Walker Percy Jordan J. Dominy Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES “THE NATURE OF THE SEARCH”: POPULAR CULTURE AND INTELLECTUAL IDENTITY IN THE WORK OF WALKER PERCY By JORDAN J. DOMINY A Thesis submitted to the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2006 The members of the Committee approve the Thesis of Jordan J. Dominy defended on April 03, 2006. Andrew Epstein Professor Directing Thesis Darryl Dickson-Carr Committee Member Leigh Edwards Committee Member Approved: Hunt Hawkins, Chair, Department of English The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii For my parents, who have always put my goals ahead of their own iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank the members of my Thesis Committee: Dr. Leigh Edwards for helping me initially narrow my focus, Dr. Andrew Epstein for directing my thesis, and Dr. Darryl Dickson-Carr for his advice and interest in the project. I thank my good friends and fellow students, Amber Pearson, Bailey Player, Alejandro Nodarse, and Jennifer Van Vliet for patiently enduring my droning about Walker Percy as I completed this project. Last but not least, I thank my wife, Jessica, for her enduring support and love. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ...............................................................................................