Local Governance: Bureaucratic Performance and Health Care Delivery in Calcutta

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE GOD THAT IS FAILING-I Bibekananda Ray

Frontier Vol. 43, No. 17, November 7-13, 2010 THE GOD THAT IS FAILING-I Bibekananda Ray In November 1949 came out a book in the USA that brought to the ken of the non-communist world the disillusion about communism of six renowned Western writers. Called 'The god that failed', it was an anthology of experiences of communist society of Arthur Koestler, Ignazio Si-lone, Richard Wright, Andre Gide, Louis Fischer and Stephen Spender who became ardent members of communist parties of their respective countries- Germany, Italy, USA, France and Britain, but quit out of frustration. It became an instant best-seller for its revelation of the workings of communist parties and governments of five countries. Alfred Hitchcock's 'Torn Curtain' (1966) was a celluloid revelation of the same in East Germany. This disillusion became a deja vous in works of many other writers and artists in countries where communism thrived. In Soviet Russia, two great writers–Boris Pasternak (1890-1960) and Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn (1918-2008) shocked readers with the persecution and honors that their protagonists experienced in two novels—Dr Zhivago (1957) and Gulag Archipelago (1973), the second a trilogy, describing a forced labour camp for dissidents in Siberia, which fetched them Nobel Prizes in literature in 1958 and 1970. A German writer, Herta Muller, awarded Nobel Prize in 2009, revealed to the world through her poems, novels and essays the oppressive regime of President Nicolae Ceauses of Romania where she was born. Ayn Rand was equally frank about the effects of communism in Germany in "We the Living'. -

India Postpoll NES 2019-Survey Findings

All India Postpoll NES 2019-Survey Findings Q1: In whatever financial condition you are placed today, on the whole are you satisfied or dissatisfied with it? N (%) 1: Fully satisfied 4937 20.4 2: Somewhat satisfied 11253 46.4 3: Somewhat dissatisfied 3777 15.6 4: Fully dissatisfied 3615 14.9 7: Can't say 428 1.8 8: No response 225 .9 Total 24235 100.0 Q2: As compared to five years ago, how is the economic condition of your household today – would you say it has become much better, better, remained same, become worse or much worse? N (%) 1: Much better 2280 9.4 2: Better 7827 32.3 3: Remained Same 10339 42.7 4: Worse 2446 10.1 5: Much worse 978 4.0 7: Can't say 205 .8 8: No response 159 .7 Total 24235 100.0 Q3: Many people talk about class nowadays, and use terms such as lower class, middle class or upper class. In your opinion, compared to other households, the household you live in currently belongs to which class? N (%) 1: Lower class 5933 24.5 2: Middle class 13459 55.5 3: Upper Class 1147 4.7 6: Poor class 1741 7.2 CSDS, LOKNITI, DELHI Page 1 All India Postpoll NES 2019-Survey Findings 7: Can't say 254 1.0 8: No response 1701 7.0 Total 24235 100.0 Q4: From where or which medium do you mostly get news on politics? N (%) 01: Television/TV news channel 11841 48.9 02: Newspapers 2365 9.8 03: Radio 247 1.0 04: Internet/Online news websites 361 1.5 05: Social media (in general) 400 1.7 06: Facebook 78 .3 07: Twitter 59 .2 08: Whatsapp 99 .4 09: Instagram 19 .1 10: Youtube 55 .2 11: Mobile phone 453 1.9 12: Friends/neighbours 695 2.9 13: -

Red Bengal's Rise and Fall

kheya bag RED BENGAL’S RISE AND FALL he ouster of West Bengal’s Communist government after 34 years in power is no less of a watershed for having been widely predicted. For more than a generation the Party had shaped the culture, economy and society of one of the most Tpopulous provinces in India—91 million strong—and won massive majorities in the state assembly in seven consecutive elections. West Bengal had also provided the bulk of the Communist Party of India– Marxist (cpm) deputies to India’s parliament, the Lok Sabha; in the mid-90s its Chief Minister, Jyoti Basu, had been spoken of as the pos- sible Prime Minister of a centre-left coalition. The cpm’s fall from power also therefore suggests a change in the equation of Indian politics at the national level. But this cannot simply be read as a shift to the right. West Bengal has seen a high degree of popular mobilization against the cpm’s Beijing-style land grabs over the past decade. Though her origins lie in the state’s deeply conservative Congress Party, the challenger Mamata Banerjee based her campaign on an appeal to those dispossessed and alienated by the cpm’s breakneck capitalist-development policies, not least the party’s notoriously brutal treatment of poor peasants at Singur and Nandigram, and was herself accused by the Communists of being soft on the Maoists. The changing of the guard at Writers’ Building, the seat of the state gov- ernment in Calcutta, therefore raises a series of questions. First, why West Bengal? That is, how is it that the cpm succeeded in establishing -

Chapter II the Geography and History of Hunger

48 Chapter II The Geography and History of Hunger In the introductory chapter, an attempt was made to understand the ‘Geography of Hunger’ theoretically. In this chapter, we would try to explore the geography as well as the history of hunger in the world in practical terms. To do so, we would go through the narratives of some of the major famines in the history of the world, which would be followed by the discussion of two devastating famines in India during the British raj. Moreover, to have an idea of the history of hunger in West Bengal in the immediate decades after independence, a descriptive study of two turbulent food movements of 1959 and 1966 in the state would also be undertaken. Nonetheless, this chapter will also try to showcase the evolution of the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) in India for it will help us to expand the horizon of our understanding of the prime food security mechanism in India. Finally, we will discuss the National Food Security Act, 2013 (NFSA) and will also undertake a study of the Right to Food movement in India. 2.1. Famines In this section, we would also try to explore the relationship between famine and politics. To illustrate, many worst famines in human history were caused by poor distribution of food due to various causes like political upheaval or natural disaster. Famines harm purchasing power, especially on the poor population. Hence, it is understandable that famines affect the population in two ways a) it disturbs the regular process of food distribution and b) it decreases the food purchasing power of the population. -

Piteous Massacre’: Violence, Language, and the Off-Stage in Richard III

Journal of the British Academy, 8(s3), 91–109 DOI https://doi.org/10.5871/jba/008s3.091 Posted 15 June 2020 ‘Piteous massacre’: violence, language, and the off-stage in Richard III Georgina Lucas Abstract: Shakespeare regularly stages extreme violence. In Titus Andronicus, Chiron and Demetrius are baked in a pie and eaten by their mother. Gloucester’s eyes are plucked out in King Lear. In contradistinction to this graphic excess are moments when violence is relegated off-stage: Macbeth kills King Duncan in private; when Richard III suborns the assassination of his nephews—the notorious ‘Princes in the Tower’—the boys are killed away from the audience. In such instances, the spectator must imagine the scope and formation of the violence described. Focussing on Richard III, this article asks why Shakespeare uses the word ‘massacre’ to express the murder of the two princes. Determining the varied, and competing, meanings of the term in the 16th and 17th centuries, the article uncovers a range of ways an early audience might have interpreted the killings—as mass murder, assassination, and butchery—and demonstrates their thematic connections to child-killing across the cycle of plays that Richard III concludes. Keywords: Shakespeare, massacre, Richard III, off-stage violence, child-killing. Notes on the author: Georgina Lucas is Lecturer in Shakespeare and Renaissance Literature in the School of Arts, English and Languages at Queen’s University, Belfast. Her research focusses upon the representation of mass and sexual violence on the early modern stage, and the performance and reception of Shakespeare during and after acts of atrocity. -

Rule Section

Rule Section CO 827/2015 Shyamal Middya vs Dhirendra Nath Middya CO 542/1988 Jayadratha Adak vs Kadan Bala Adak CO 1403/2015 Sankar Narayan das vs A.K.Banerjee CO 1945/2007 Pradip kr Roy vs Jali Devi & Ors CO 2775/2012 Haripada Patra vs Jayanta Kr Patra CO 3346/1989 + CO 3408/1992 R.B.Mondal vs Syed Ali Mondal CO 1312/2007 Niranjan Sen vs Sachidra lal Saha CO 3770/2011 lily Ghose vs Paritosh Karmakar & ors CO 4244/2006 Provat kumar singha vs Afgal sk CO 2023/2006 Piar Ali Molla vs Saralabala Nath CO 2666/2005 Purnalal seal vs M/S Monindra land Building corporation ltd CO 1971/2006 Baidyanath Garain& ors vs Hafizul Fikker Ali CO 3331/2004 Gouridevi Paswan vs Rajendra Paswan CR 3596 S/1990 Bakul Rani das &ors vs Suchitra Balal Pal CO 901/1995 Jeewanlal (1929) ltd& ors vs Bank of india CO 995/2002 Susan Mantosh vs Amanda Lazaro CO 3902/2012 SK Abdul latik vs Firojuddin Mollick & ors CR 165 S/1990 State of west Bengal vs Halema Bibi & ors CO 3282/2006 Md kashim vs Sunil kr Mondal CO 3062/2011 Ajit kumar samanta vs Ranjit kumar samanta LIST OF PENDING BENCH LAWAZIMA : (F.A. SECTION) Sl. No. Case No. Cause Title Advocate’s Name 1. FA 114/2016 Union Bank of India Mr. Ranojit Chowdhury Vs Empire Pratisthan & Trading 2. FA 380/2008 Bijon Biswas Smt. Mita Bag Vs Jayanti Biswas & Anr. 3. FA 116/2016 Sarat Tewari Ms. Nibadita Karmakar Vs Swapan Kr. Tewari 4. -

Don't Talk About Khalistan but Let It Brew Quietly. Police Say Places Where Religious

22 MARCH 2021 / `50 www.openthemagazine.com CONTENTS 22 MARCH 2021 5 6 12 14 16 18 LOCOMOTIF bengAL DIARY INDIAN ACCENTS TOUCHSTONE WHISPERER OPEN ESSAY The new theology By Swapan Dasgupta The first translator The Eco chamber By Jayanta Ghosal Imperfect pitch of victimhood By Bibek Debroy By Keerthik Sasidharan By James Astill By S Prasannarajan 24 24 AN EAST BENGAL IN WEST BENGAL The 2021 struggle for power is shaped by history, geography, demography—and a miracle by the Mahatma By MJ Akbar 34 THE INDISCREET CHARM OF ABBAS SIDDIQUI Can the sinking Left expect a rainmaker in the brash cleric, its new ally? By Ullekh NP 38 A HERO’S WELCOME 40 46 Former Naxalite, king of B-grade films and hotel magnate Mithun Chakraborty has traversed the political spectrum to finally land a breakout role By Kaveree Bamzai 40 HARVESTING A PROTEST If there is trouble from a resurgent Khalistani politics in Punjab, it is unlikely to follow the 50 54 roadmap of the 1980s By Siddharth Singh 46 TURNING OVER A NEW LEAF The opportunities and pains of India’s tiny seaweed market By Lhendup G Bhutia 62 50 54 60 62 65 66 OWNING HER AGE THE VIOLENT INDIAN PAGE TURNER BRIDE, GROOM, ACTION HOLLYWOOD REPORTER STARGAZER Pooja Bhatt, feisty teen Thomas Blom Hansen The eternity of return The social realism of Viola Davis By Kaveree Bamzai idol and magazine cover on his new book By Mini Kapoor Indian wedding shows on her latest film magnet of the 1990s, is back The Law of Force: The Violent By Aditya Mani Jha Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom By Kaveree Bamzai Heart of Indian Politics -

West Bengal from an External Perspective Technical Session at the 4Th West Bengal Growth Workshop Indian Statistical Institute December 27, 2014, 3:30-4:30 Pm

West Bengal from an External Perspective Technical session at the 4th West Bengal Growth Workshop Indian Statistical Institute December 27, 2014, 3:30-4:30 pm Ashok K. Lahiri I am grateful to the organisers for inviting me to this session to share my thoughts on West Bengal from an external perspective. I must confess that my perspective can never be completely external since I still consider West Bengal as my ‘home’, and furthermore, even the ‘outsider’s perspective’ that I was gaining when for six years I was at the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in Manila, is fading since I returned in July 2013. Still, let me try to say a few words about the economy of West Bengal, not exclusively but with some reference to ADB’s involvement in West Bengal. In an article “A Look in the Mirror” in ‘The Outlook’ on March 31, 2014, before the recent Lok Sabha elections, Professors Maitreesh Ghatak and Sanchari Roy compared the economic performance of Gujarat under Narendra Modi with some of the best performing of the 16 major populated states of India during 1980-2010. Criteria were level and growth of per capita income, human development index, inequality, and people below the poverty line. Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu came up for special mention. Even Andhra Pradesh was mentioned for low levels of poverty, Assam for low level of inequality, Bihar for growth of per capita income, and Rajasthan for low and declining inequality. There was no mention of West Bengal. Yet, in 1980-81, in per capita income, Bengal ranked fifth after Gujarat, Haryana, Maharashtra and Punjab. -

Left Front Government in West Bengal (1971-1982) (PP93)

People, Politics and Protests VIII LEFT FRONT GOVERNMENT IN WEST BENGAL (1971-1982) Considerations on “Passive Revolution” & the Question of Caste in Bengal Politics Atig Ghosh 2017 LEFT FRONT GOVERNMENT IN WEST BENGAL (1971-1982) Considerations on “Passive Revolution” & the Question of Caste in Bengal Politics ∗ Atig Ghosh The Left Front was set up as the repressive climate of the Emergency was relaxed in January 1977. The six founding parties of the Left Front, i.e. the Communist Party of India (Marxist) or the CPI(M), the All India Forward Bloc (AIFB), the Revolutionary Socialist Party (RSP), the Marxist Forward Bloc (MFB), the Revolutionary Communist Party of India (RCPI) and the Biplabi Bangla Congress (BBC), articulated a common programme. This Left Front contested the Lok Sabha election in an electoral understanding together with the Janata Party and won most of the seats it contested. Ahead of the subsequent June 1977 West Bengal Legislative Assembly elections, seat- sharing talks between the Left Front and the Janata Party broke down. The Left Front had offered the Janata Party 56 per cent of the seats and the post as Chief Minister to JP leader Prafulla Chandra Sen, but JP insisted on 70 per cent of the seats. The Left Front thus opted to contest the elections on its own. The seat-sharing within the Left Front was based on the “Promode Formula”, named after the CPI(M) State Committee Secretary Promode Das Gupta. Under the Promode Formula the party with the highest share of votes in a constituency would continue to field candidates there, under its own election symbol and manifesto. -

Partial List of Mass Execution of Oromos and Other Nation And

Udenrigsudvalget 2013-14 URU Alm.del Bilag 174 Offentligt Partial list of Mass execution of Oromos and other nation and nationalities of Ethiopia (Documented by Oromo Liberation Front Information and Research Unit, March 2014) Injustice anywhere is injustice everywhere!!! Ethiopia is one of the Countries at Genocide Risk in accordance with Genocide Watch’s Report released on March 12, 2013. •Genocide Watch considers Ethiopia to have already reached Stage 7, genocidal massacres, against many of its peoples, including the Anuak, Ogadeni, Oromo and Omo tribes. •We recommend that the United States government immediately cease all military assistance to the Ethiopian Peoples Defense Forces. We also recommend strong diplomatic protests to the Meles Zenawi regime against massive violations of human rights in Ethiopia Article 281 of the Ethiopian Penal Code : Genocide; Crimes against Humanity Whosoever, with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial, religious or political group, organizes, orders or engages in, be it in time of war or in time of peace: (a) killings, bodily harm or serious injury to the physical or mental health of members of the group, in any way whatsoever; or (b) measures to prevent the propagation or continued survival of its members or their progeny; or (c) the compulsory movement or dispersion of peoples or children, or their placing under living conditions calculated to result in their death or disappearance, is punishable with rigorous imprisonment from five years to life, or, in cases of exceptional -

Bengal-Bangladesh Border and Women

The Bengal-Bangladesh Borderland: Chronicles from Nadia, Murshidabad and Malda 1 Paula Banerjee Introduction Borderland studies, particularly in the context of South Asia are a fairly recent phenomenon. I can think of three works that have made borderlands, particularly the Bengal-Bangladesh borderland as the focal area of their study in the last one decade. Ranabir Samaddar’s The Marginal Nation: Transborder Migration From Bangladesh to West Bengal started a trend that was continued by Willem Van Schendel in his The Bengal Borderland: Beyond State and Nation in South Asia . Both these books argue that the border is part of larger zone or the borderland that at once constructs and subverts the nation. Samaddar goes beyond the security and immutable border discourse and problematises the borderland by speaking of flows across the border. He argues that such flows are prompted by historical and social affinities, geographical contiguity and economic imperative. People move when their survival is threatened and rigid borders mean little to the desperate. They question the nation form that challenges their existence. If need be they find illegal ways to tackle any obstacle that stand in their path of moving particularly when that makes the difference between life and death. Thereby Samaddar questions ideas of nation state and national security in present day South Asia when and if it privileges land over the people who inhabit that land. Van Schendel also takes the argument along similar lines by stating that without understanding the borderland it is impossible to understand the nation form that develops in South Asia, the economy that emerges or the ways in which national identities are internalized. -

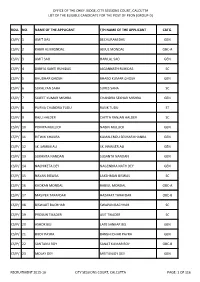

Office of the Chief Judge, City Sessions Court, Calcutta List of the Eligible Candidate for the Post of Peon (Group-D) Roll

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUDGE, CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA LIST OF THE ELIGIBLE CANDIDATE FOR THE POST OF PEON (GROUP-D) ROLL NO. NAME OF THE APPLICANT F/H NAME OF THE APPLICANT CATG. CS/P/ 1 AMIT DAS BECHURAM DAS GEN CS/P/ 2 KABIR ALI MONDAL AJIJUL MONDAL OBC-A CS/P/ 3 AMIT SAO HARILAL SAO GEN CS/P/ 4 DIBBYA KANTI RUHIDAS JAGANNATH RUHIDAS SC CS/P/ 5 BHUDHAR GHOSH BHABO KUMAR GHOSH GEN CS/P/ 6 SUKALYAN SAHA SURES SAHA SC CS/P/ 7 SUJEET KUMAR MISHRA CHANDRA SEKHAR MISHRA GEN CS/P/ 8 PURNA CHANDRA TUDU RASIK TUDU ST CS/P/ 9 RAJU HALDER CHITTA RANJAN HALDER SC CS/P/ 10 POMPA MULLICK NABIN MULLICK GEN CS/P/ 11 RITWIK KHANRA KAMALENDU SEKHAR KHANRA GEN CS/P/ 12 SK. SAMIM ALI SK. NAWSER ALI GEN CS/P/ 13 SUKANTA NANDAN SUSANTA NANDAN GEN CS/P/ 14 NACHIKETA DEY NAGENDRA NATH DEY GEN CS/P/ 15 NAYAN BISWAS LAKSHMAN BISWAS SC CS/P/ 16 KHOKAN MONDAL RABIUL MONDAL OBC-A CS/P/ 17 MASIYER TARAFDAR HAZARAT TARAFDAR OBC-B CS/P/ 18 BISWAJIT BACHHAR SWAPAN BACHHAR SC CS/P/ 19 PROSUN TIKADER ASIT TIKADER SC CS/P/ 20 ASHOK BEJ LATE SANKAR BEJ GEN CS/P/ 21 BIJOY PAYRA BANSHI DHAR PAYRA GEN CS/P/ 22 SANTANU ROY SANAT KUMAR ROY OBC-B CS/P/ 23 MOLAY DEY MRITUNJOY DEY GEN RECRUITMENT 2015-16 CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA PAGE: 1 OF 116 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUDGE, CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA LIST OF THE ELIGIBLE CANDIDATE FOR THE POST OF PEON (GROUP-D) ROLL NO.