West Bengal from an External Perspective Technical Session at the 4Th West Bengal Growth Workshop Indian Statistical Institute December 27, 2014, 3:30-4:30 Pm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter II the Geography and History of Hunger

48 Chapter II The Geography and History of Hunger In the introductory chapter, an attempt was made to understand the ‘Geography of Hunger’ theoretically. In this chapter, we would try to explore the geography as well as the history of hunger in the world in practical terms. To do so, we would go through the narratives of some of the major famines in the history of the world, which would be followed by the discussion of two devastating famines in India during the British raj. Moreover, to have an idea of the history of hunger in West Bengal in the immediate decades after independence, a descriptive study of two turbulent food movements of 1959 and 1966 in the state would also be undertaken. Nonetheless, this chapter will also try to showcase the evolution of the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) in India for it will help us to expand the horizon of our understanding of the prime food security mechanism in India. Finally, we will discuss the National Food Security Act, 2013 (NFSA) and will also undertake a study of the Right to Food movement in India. 2.1. Famines In this section, we would also try to explore the relationship between famine and politics. To illustrate, many worst famines in human history were caused by poor distribution of food due to various causes like political upheaval or natural disaster. Famines harm purchasing power, especially on the poor population. Hence, it is understandable that famines affect the population in two ways a) it disturbs the regular process of food distribution and b) it decreases the food purchasing power of the population. -

Rule Section

Rule Section CO 827/2015 Shyamal Middya vs Dhirendra Nath Middya CO 542/1988 Jayadratha Adak vs Kadan Bala Adak CO 1403/2015 Sankar Narayan das vs A.K.Banerjee CO 1945/2007 Pradip kr Roy vs Jali Devi & Ors CO 2775/2012 Haripada Patra vs Jayanta Kr Patra CO 3346/1989 + CO 3408/1992 R.B.Mondal vs Syed Ali Mondal CO 1312/2007 Niranjan Sen vs Sachidra lal Saha CO 3770/2011 lily Ghose vs Paritosh Karmakar & ors CO 4244/2006 Provat kumar singha vs Afgal sk CO 2023/2006 Piar Ali Molla vs Saralabala Nath CO 2666/2005 Purnalal seal vs M/S Monindra land Building corporation ltd CO 1971/2006 Baidyanath Garain& ors vs Hafizul Fikker Ali CO 3331/2004 Gouridevi Paswan vs Rajendra Paswan CR 3596 S/1990 Bakul Rani das &ors vs Suchitra Balal Pal CO 901/1995 Jeewanlal (1929) ltd& ors vs Bank of india CO 995/2002 Susan Mantosh vs Amanda Lazaro CO 3902/2012 SK Abdul latik vs Firojuddin Mollick & ors CR 165 S/1990 State of west Bengal vs Halema Bibi & ors CO 3282/2006 Md kashim vs Sunil kr Mondal CO 3062/2011 Ajit kumar samanta vs Ranjit kumar samanta LIST OF PENDING BENCH LAWAZIMA : (F.A. SECTION) Sl. No. Case No. Cause Title Advocate’s Name 1. FA 114/2016 Union Bank of India Mr. Ranojit Chowdhury Vs Empire Pratisthan & Trading 2. FA 380/2008 Bijon Biswas Smt. Mita Bag Vs Jayanti Biswas & Anr. 3. FA 116/2016 Sarat Tewari Ms. Nibadita Karmakar Vs Swapan Kr. Tewari 4. -

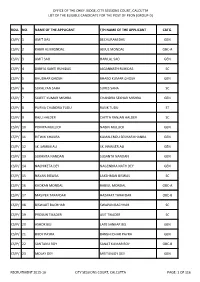

Office of the Chief Judge, City Sessions Court, Calcutta List of the Eligible Candidate for the Post of Peon (Group-D) Roll

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUDGE, CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA LIST OF THE ELIGIBLE CANDIDATE FOR THE POST OF PEON (GROUP-D) ROLL NO. NAME OF THE APPLICANT F/H NAME OF THE APPLICANT CATG. CS/P/ 1 AMIT DAS BECHURAM DAS GEN CS/P/ 2 KABIR ALI MONDAL AJIJUL MONDAL OBC-A CS/P/ 3 AMIT SAO HARILAL SAO GEN CS/P/ 4 DIBBYA KANTI RUHIDAS JAGANNATH RUHIDAS SC CS/P/ 5 BHUDHAR GHOSH BHABO KUMAR GHOSH GEN CS/P/ 6 SUKALYAN SAHA SURES SAHA SC CS/P/ 7 SUJEET KUMAR MISHRA CHANDRA SEKHAR MISHRA GEN CS/P/ 8 PURNA CHANDRA TUDU RASIK TUDU ST CS/P/ 9 RAJU HALDER CHITTA RANJAN HALDER SC CS/P/ 10 POMPA MULLICK NABIN MULLICK GEN CS/P/ 11 RITWIK KHANRA KAMALENDU SEKHAR KHANRA GEN CS/P/ 12 SK. SAMIM ALI SK. NAWSER ALI GEN CS/P/ 13 SUKANTA NANDAN SUSANTA NANDAN GEN CS/P/ 14 NACHIKETA DEY NAGENDRA NATH DEY GEN CS/P/ 15 NAYAN BISWAS LAKSHMAN BISWAS SC CS/P/ 16 KHOKAN MONDAL RABIUL MONDAL OBC-A CS/P/ 17 MASIYER TARAFDAR HAZARAT TARAFDAR OBC-B CS/P/ 18 BISWAJIT BACHHAR SWAPAN BACHHAR SC CS/P/ 19 PROSUN TIKADER ASIT TIKADER SC CS/P/ 20 ASHOK BEJ LATE SANKAR BEJ GEN CS/P/ 21 BIJOY PAYRA BANSHI DHAR PAYRA GEN CS/P/ 22 SANTANU ROY SANAT KUMAR ROY OBC-B CS/P/ 23 MOLAY DEY MRITUNJOY DEY GEN RECRUITMENT 2015-16 CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA PAGE: 1 OF 116 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUDGE, CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA LIST OF THE ELIGIBLE CANDIDATE FOR THE POST OF PEON (GROUP-D) ROLL NO. -

In the High Court at Calcutta

IN THE HIGH COURT AT CALCUTTA APPELLATE JURISDICTION SUPPLEMENTARY LIST TO THE COMBINED MONTHLY LIST OF CASES ON AND FROM , MONDAY, THE 5TH JUNE, 2017, FOR HEARING ON MONDAY, THE 5TH JUNE, 2017. INDEX SL. BENCHES COURT TIME PAGE NO. ROOM NO. NO. 1. THE HON’BLE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE NISHITA MHATRE 1 AND (DB – I) THE HON’BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY THE HON’BLE JUSTICE PATHERYA ON AND 2. AND 8 FROM THE HON’BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 05.06.2017 FROM 10.30 A.M. TILL 1.15 P.M. ON AND 3. THE HON’BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 29 FROM 05.06.2017 FROM 2.00 P.M. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- *********************************************************************** ********* 05/06/2017 COURT NO. 1 FIRST FLOOR THE HON'BLE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE NISHITA MHATRE AND HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY *********************************************************************** ********* (DB – I) ON AND FROM MONDAY, THE 10TH APRIL, 2017 - Writ Appeals relating to Service (Gr.-VI); WRIT APPEALS RELATING TO (GR.-IX) RESIDUARY; CONTEMPT SEC. 19(A), SEC. 27 OF ELECTRICITY REG. PIL, Matters under Article 226/227 of the Constitution of India relating to Tribunals under Art. 323A and applications thereto; Writ Appeals not assigned to any other bench. And On and from Monday, the 5th June 2017 to Friday, the 9th June, 2017 (Both days inclusive) – will take, in addition to their own list and determination, urgent matters relating to the list and determination of the Division Bench comprising Hon’ble Justice Sanjib Banerjee and Hon’ble Justice Siddhartha Chattopadhyay. NOTE : On and from 9.1.2017, Tribunal motions, applications and hearing will be taken up during the entire week and other matters will be taken up in the following week. -

Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950S

People, Politics and Protests I Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950s – 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Anwesha Sengupta 2016 1. Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee 1 2. Tram Movement and Teachers’ Movement in Calcutta: 1953-1954 Anwesha Sengupta 25 Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s ∗ Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Introduction By now it is common knowledge how Indian independence was born out of partition that displaced 15 million people. In West Bengal alone 30 lakh refugees entered until 1960. In the 1970s the number of people entering from the east was closer to a few million. Lived experiences of partition refugees came to us in bits and pieces. In the last sixteen years however there is a burgeoning literature on the partition refugees in West Bengal. The literature on refugees followed a familiar terrain and set some patterns that might be interesting to explore. We will endeavour to explain through broad sketches how the narratives evolved. To begin with we were given the literature of victimhood in which the refugees were portrayed only as victims. It cannot be denied that in large parts these refugees were victims but by fixing their identities as victims these authors lost much of the richness of refugee experience because even as victims the refugee identity was never fixed as these refugees, even in the worst of times, constantly tried to negotiate with powers that be and strengthen their own agency. But by fixing their identities as victims and not problematising that victimhood the refugees were for a long time displaced from the centre stage of their own experiences and made “marginal” to their narratives. -

Download West Bengal 1971 General Election Report

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTION, 1971 TO THE LEGISLATIVE ASSEMBLY OF WEST BENGAL ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI Election Commission of India – General Election, 1971 to the Legislative Assembly of West Bengal STATISTICAL REPORT CONTENTS SUBJECT Page no. 1. List of Participating Political Parties and Abbreviations 1 2. Other Abbreviations in the Report 2 3. Highlights 3 4. List of Successful Candidates 4 - 10 5. Performance of Political Parties 11 - 12 6. Electors Data Summary – Summary on Electors, voters Votes Polled and Polling Stations 13 7. Constituency Data Summary 14 - 292 8. Detailed Result 293 - 336 Election Commission of India-State Elections,1971 to the Legislative Assembly of West Bengal LIST OF PARTICIPATING POLITICAL PARTIES PARTYTYPE ABBREVIATION PARTY NATIONAL PARTIES 1 . BJS BHARATIYA JANA SANGH 2 . CPI COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 3 . CPM COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST) 4 . INC INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS 5 . NCO INDIAN NATIONAL CONGRESS (ORGANISATION) 6 . PSP PRAJA SOCIALIST PARTY STATE PARTIES 7 . FBL ALL INDIA FORWARD BLOCK 8 . RPI REPUBLICAN PARTY OF INDIA 9 . RSP REVOLUTIONERY SOCIALIST PARTY REGISTERED(Unrecognised ) PARTIES 10 . BAC BANGAL CONGRESS 11 . BBC BHARATER BIPLABI COMMUNIST PARTY 12 . BIB BIPALBI BANGLA CONGRESS 13 . HMS AKHIL BHARAT HINDU MAHASABHA 14 . IGL ALL INDIA GORKHA LEAGUE 15 . JKP ALL INDIA JHARKHAND PARTY 16 . LSS LOK SEVAK SANGHA 17 . MFB MARXIST FORWARD BLOCK 18 . PML PROGRESSIVE MUSLIM LEAGUE 19 . RCI REVOLUTIONARY COMMUNIST PARTY OF INDIA 20 . RSM REVOLUTIONARY SOCIALIST PARTY OF INDIA (MARXIST LENINI 21 . SML WEST BENGAL STATE MUSLIM LEAGUE 22 . SOC SOCIALIST PARTY 23 . SSP SAMYUKTA SOCIALIST PARTY 24 . SUC SOCIALIST UNITY CENTRE OF INDIA 25 . -

Congress in the Politics of West Bengal: from Dominance to Marginality (1947-1977)

CONGRESS IN THE POLITICS OF WEST BENGAL: FROM DOMINANCE TO MARGINALITY (1947-1977) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH BENGAL For the award of Doctor of Philosophy In History By Babulal Bala Assistant Professor Department of History Raiganj University Raiganj, Uttar Dinajpur, 733134 West Bengal Under the Supervision of Dr. Ichhimuddin Sarkar Former Professor Department of History University of North Bengal November, 2017 1 2 3 4 CONTENTS Page No. Abstract i-vi Preface vii Acknowledgement viii-x Abbreviations xi-xiii Introduction 1-6 Chapter- I The Partition Colossus and the Politics of Bengal 7-53 Chapter-II Tasks and Goals of the Indian National Congress in West Bengal after Independence (1947-1948) 54- 87 Chapter- III State Entrepreneurship and the Congress Party in the Era of Dr. Bidhan Chandra Roy – Ideology verses Necessity and Reconstruction 88-153 Chapter-IV Dominance with a Difference: Strains and Challenges (1962-1967) 154-230 Chapter- V Period of Marginalization (1967-1971): 231-339 a. Non-Congress Coalition Government b. Presidential Rule Chapter- VI Progressive Democratic Alliance (PDA) Government – Promises and Performances (1972-1977) 340-393 Conclusion 394-395 Bibliography 396-406 Appendices 407-426 Index 427-432 5 CONGRESS IN THE POLITICS OF WEST BENGAL: FROM DOMINANCE TO MARGINALITY (1947-1977) ABSTRACT Fact remains that the Indian national movement found its full-flagged expression in the activities and programmes of the Indian National Congress. But Factionalism, rival groupism sought to acquire control over the Congress time to time and naturally there were confusion centering a vital question regarding ‘to be or not to be’. -

National Revolutionism to Marxism – a Narrative of Origins of Socialist Unity Centre of India

NATIONAL REVOLUTIONISM TO MARXISM – A NARRATIVE OF ORIGINS OF SOCIALIST UNITY CENTRE OF INDIA Dr. Bikash Ranjan Deb Associate Professor of Political Science Surya Sen Mahavidyalaya Siliguri, West Bengal, India [email protected] INTRODUCTION: The national revolutionary movement, one of the early trends of ‘Swadeshi Movement’, constituted a significant aspect in the history of the Indian freedom movement. The colonial rulers, however, preferred the term ‘terrorism’1 to denigrate the movement. For the purpose of the present study, let us confine the term ‘national revolutionism’ following Gopal Halder, ‘to describe a pattern of activity pursued for a prolonged period of thirty years, from 1904 to 1934’. (Halder, 2002: 195; Habib, S. Irfan, 2017: 2)2 Imbued with the spirit of unrelenting fight against British imperial power in India, the national revolutionaries tried to set before the people of the country a bright example of personal courage and heroic self-sacrifice, and thereby wanted to instill a mood of defiance in the minds of the people in the face of colonial repression. The national revolutionaries represented the uncompromising trend of Indian freedom movement in terms of both their willingness and their activities for complete national freedom and people’s liberation from colonial exploitation, by arousing revolutionary upsurge. But this was not the dominant trend of the national freedom struggle. The reformist and compromising section of the Indian National Congress (INC) playing the role of ‘reformist oppositional’ was the -

Comrade Ranjit Dhar Devoted His Entire Life to Firmly Uphold the Cause

Volume 52 No. 23 Organ of the SOCIALIST UNITY CENTRE OF INDIA (COMMUNIST) 8 Pages July 15, 2019 Founder Editor-in-Chief : COMRADE SHIBDAS GHOSH Price : Rs. 2.00 LONG LIVE COMRADE ENGELS “…the bourgeoisie defends its interests with all the power placed at its disposal by wealth and the might of the estate...the law is sacred to the bourgeois, for it is his own composition, enacted with his consent, and for his benefit and protection...and more than all, the sanctity of the law, the sacredness of order as established by the active will of one part of the society, and the passive acceptance of the other, is the strongest support of his social position. ...But for the working-man quite otherwise! The working-man knows too well, as learned from too oft-repeated experience, that the law is a rod which the bourgeois has prepared for him; ...Since, however, the. bourgeoisie cannot dispense with government but must have it to hold the equally indispensable proletariat in check, it turns the power of government against the 28 November 1820 – 5 August 1895 proletariat and keeps out of its way as far as possible.” (The Condition of the Working Class in England) Comrade Ranjit Dhar devoted SUCI(C) calls the Union Budget a masterly crafted his entire life to firmly uphold document to grease the rich and fleece the poor In a quick response to the Union Budget the cause of the working class 2019 presented in Parliament on 5 July 2019, Comrade Provash Ghosh, General Comrade Provash Ghosh at the Memorial Meeting Secretary, SUCI(C), issued the following [This is the text of the speech delivered in Bengali by Comrade Provash Ghosh, General Secretary, statement on the same day : SUCI(C), at the Memorial Meeting of Comrade Ranjit Dhar, veteran Polit Bureau Member of the Cunningly bypassing the pressing Party, held on 21 June 2019, at Sarat Sadan, Howrah, West Bengal. -

Chapter-V Period of Marginalization (1967-1971)

CHAPTER-V PERIOD OF MARGINALIZATION (1967-1971): A. NON-CONGRESS COALITION GOVERNMENT AND B. PRESIDENTIAL RULE A political reconstruction throughout the country and the All India Congress Party started unfolding the stratigies in the late 1960s. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s various steps regarding economic stance were not appreciated by the senior Congress leadership those who were popularly known as ‘syndicate’. The so called ‘syndicate’ group had started asserting themselves in post Nehru era on the ground of their seniority and experience which was counted more than important that of the political novice of Indira Gandhi. The senior as well as prominent Congress leaders like – K. Kamraj Nadar, S. Nijalingappa. S. K. Patil, Atulya Ghosh, C. Subramaniam, Neelam Sanjiva Reddy etc. collectively had formed an unconventional group at the aim of pressuring on Indira Gandhi to work on their advice.1 New Era- The All India Scenario Before the election of 1967 the so-called sundicate group leaders were sometimes succeeded to compel Indira Gandhi to act according to their advice. In that context, it may be mentioned that in case of the removal of G. L. Nanda from the portfolio of Home Ministy and Prime Minister had to resile regarding the keeping of Finance Minister Sachin Choudhury and Commerce Minister Munabhai Shah in their respective portfolio due to the pressure of syndicate group.2 But, the target of the syndicate group however, was not fulfilled as because most of these leaders were defeated in the election of 1967. The fourth general election was so detrimental for Congress party in India that for the first time after independence Congress had failed to form Governments in West Bengal, Bihar, Orissa, Tamil Nadu and Kerala due to lack of majority. -

Ward No: 125 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 125 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 MASJID PARA JAYEGIR GHAT ROAD AARFIN AHMED LATE ABDUL OWASE 1 1 2 1 2 ANANDA NAGAR KHALPAR H37/22 SOUTH BEHALA ROAD ABANI HALDER LATE M. HALDER 2 4 6 2 3 BHATTYACHARJEE PARA 72E BHATTYACHARJEE PARA ABANI MOHAN DAS LATE ASHWINI DAS 3 2 5 3 4 PANER ARA 188/B/1 JAYGIR GHAT ROAD ABANTI BARA SAMAL BARA 1 3 4 4 5 NAZRUL SARANI BAKHRA HUT ROAD ABBAS ALI MONDAL IMAM BAKSH MONDAL 4 1 5 5 6 PASCHIM PARA NA PANCH MASJID ABBAS ANSARY IMDAJ ALI 1 2 3 6 7 . ABBASUDDIN 2 3 5 7 8 NA 118 BHATTACHERJEE PARA ABDUL AHAN KHAN NA 4 4 8 8 9 MOROL PARA 2 JAYGIR GHAT ROAD ABDUL AJIJ LT ABDUL JABBAR 1 0 1 9 10 152/6 JOY KULLA MOLLA ROAD ABDUL HAMID KHAN ABDUL GHANI KHAN 2 2 4 11 11 NA 54/4 AMRITA LAL MUKHERJEE ROAD ABDUL HANNAN ABDUL KHALEK 2 2 4 12 12 GANIPARA JAIGIR GHAT ROAD ABDUL MAJID LATE ABDUL JALIL 1 3 4 13 13 PASCHIM PARA NA PANCH MASJID ABDUL RAFIK LATIF PAYADA 2 2 4 14 14 MASJID PARA 331 JAIGIR GHAT ROAD ABDUL RASHID HALDER ABDUL REZAK HALDER 2 1 3 15 15 NA 118 BHATTACHERJEE PARA ABDUL SAHAJAN NA 4 1 5 16 16 SASHIBHUSAN BANERJEE ROAD ABDUL SAMAD 2 1 3 17 17 MOROL PARA NA JAYGIR GHAT ROAD ABDUL SATTAR ABDUR RAHAMAN 2 2 4 18 18 MASJID PARA PANCH MASJID ABDUS SALAM LATE JASIMUDDIN 3 2 5 19 19 MOLLICK PARA NA JAYGIR GHAT ROAD ABID HOSAN AHAMAD HOSAN 2 2 4 20 20 MALLICK PARA JAIGIR GHAT ROAD ABID MALLICK LATE AMMAD HOSSAIN MALLIC 2 2 4 21 21 DARGATALA JAIGIR GHAT ROAD ABJEN MALLICK LATE YEASIN MALLICK 1 3 4 22 22 MALLICK PARA JAIGIR GHAT ROAD ABUKASEM MALLICK LATE BHOLA MALLICK 1 3 4 23 23 MASJID PARA JAYEGIR GHAT ROAD ABUL HOSSAIN LATE SHAH ALAM 3 3 6 24 24 MALLICK PARA JAIGIR GHAT ROAD ACHIYA BEWA 3 1 4 25 25 SABUJ PARK NA 2 NO. -

1. Please Refer to Employment Notice No FRC/Recruit/10/2018 Dated 29/10/2018

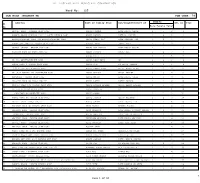

1. Please refer to Employment Notice No FRC/Recruit/10/2018 Dated 29/10/2018. 2. The following candidates have been selected after scrutiny of documents to appear before the Board of Officers for Physical and Viva test at Police Training School, 247 A J C Bose Road, Kolkata-700027 as mentioned date against their names:- Note:- 1. No separate call letter is being sent to individual candidate. 2. No candidate will be entertained if he/she is late by 30 minutes. DATE & TIME OF TEST SL NO ID NO NAME FATHERS NAME MOBILE NO (Place-PTS Parade Ground) 1 L0001 PURNIMA DASGUPTA DAS BABLU DAS 9831307403 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 2 L0002 SUSMITA MUKHERJEE KRISNENDU MUKHERJEE 7003405131 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 3 L0003 NUPUR MAJUMDER LT BIJOY KRISHNA MAJUMDER 9836166749 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 4 L0004 TANDRA NASKAR KARTICK NASKAR 8017652767 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 5 L0005 PALLABI MANNA KASHINATH MANNA 9083735547 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 6 L0006 ANUSUA DEBI ROY MANICK CHANDRA ROY 9051129264 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 7 L0007 TANDRANI DARDAR JAGADISH SARDAR 9093214400 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 8 L0008 MITHU CHAKRABORTY PRADIP KUMAR CHAKRABORTY 9903703566 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 9 L0009 PRITI NASKAR SUKDEV NASKAR 8272996708 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 10 L0010 NAZIMA PARVIN MD KHALIL MOLLA 9143931500 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 11 L0011 MINI SANPUI MANMATHA SANPUI 9831668145 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 12 L0012 TAPASI MUKHERJEE MANTU ADHIKARI 8902344665 3rd December, 2018 at 0600 hrs 13 L0013 BEAUTI