Fare Hike and Urban Protest Calcutta Crowd in 1953 Siddhartha Guha Roy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bibliography

Bibliography 337 Bibliography A.Primary Sources 1. Committee of Ministers‟ Report. 2. WBLA, Vol. XVII, No.2, 1957. 3. Committee of Review of Rehabilitation Report on the Medical Facilities for New Migrants from Erstwhile East Pakistan in West Bengal. 4. Committee of Review of Rehabilitation Report on the Education Facilities for New Migrants from Erstwhile East Pakistan in West Bengal. 5. WBLA, Vol. XIV, No. 1, 1956. 6. Committee of Review of Rehabilitation Report on Rehabilitation of Displaced Persons from Erstwhile East Pakistan in West Bengal, Third Report. 7. Working Group Report on the Residual problem of Rehabilitation. 8. S. K. Gupta Papers, File Doc. DS: „DDA- Official Documents‟, NMML. 9. 6th Parliament Estimate Committee 30th Report. 10. Indian Parliament, Estimates Committee Report, 30th Report. Dandakaranya Project: Exodus of Settlers, New Delhi, 1979. 11. Estimate Committee, 1959-60, Ninety-Sixth Report, Second Loksabha. 12. WBLA, Vol. XV, No.2, 1957 13. Ninety-Sixth Report of the Estimates Committee, 1959-60, (Second Loksabha) 14. UCRC Executive Committee‟s Report, 16th Convention. 15. Govt. of West Bengal, Master Plan. 16. SP Mukherjee Papers, NMML. 17. Council Debates (Official report), West Bengal Legislative Council, First Session, June – August 1952, vol. I. Census Report 1. Census Report of 1951, Government of West Bengal, India. 2. Census of India 1961, Vol. XVI, part I-A, book (i), p.175. 3. Census Report, 1971. 4. Census of India, 2001. 338 Official and semi-official publications 1. Dr. Guha, B. S., Memoir No. 1, 1954. Studies in Social Tensions among the Refugees from Eastern Pakistan, Department of Anthropology, Government of India, Calcutta, 1959. -

Chapter II the Geography and History of Hunger

48 Chapter II The Geography and History of Hunger In the introductory chapter, an attempt was made to understand the ‘Geography of Hunger’ theoretically. In this chapter, we would try to explore the geography as well as the history of hunger in the world in practical terms. To do so, we would go through the narratives of some of the major famines in the history of the world, which would be followed by the discussion of two devastating famines in India during the British raj. Moreover, to have an idea of the history of hunger in West Bengal in the immediate decades after independence, a descriptive study of two turbulent food movements of 1959 and 1966 in the state would also be undertaken. Nonetheless, this chapter will also try to showcase the evolution of the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) in India for it will help us to expand the horizon of our understanding of the prime food security mechanism in India. Finally, we will discuss the National Food Security Act, 2013 (NFSA) and will also undertake a study of the Right to Food movement in India. 2.1. Famines In this section, we would also try to explore the relationship between famine and politics. To illustrate, many worst famines in human history were caused by poor distribution of food due to various causes like political upheaval or natural disaster. Famines harm purchasing power, especially on the poor population. Hence, it is understandable that famines affect the population in two ways a) it disturbs the regular process of food distribution and b) it decreases the food purchasing power of the population. -

Indian Institute of Technology

INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Kharagpur 721302, West Bengal Tel : 03222-282002, 255386, 277201, 282022, 255622, 282023 Fax : 03222-282020, 255303 Email : [email protected], [email protected] Website : http://www.iitkgp.ernet.in The Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur (IIT Kharagpur or IIT KGP) is a public engineering institution established by the government of India in 1951. The first of the IITs to be established, it is recognized as an Institute of National Importance by the government of India. The institute was established to train scientists and engineers after India attained independence in 1947. It shares its organisational structure and undergraduate admission process with sister IITs. The students and alumni of IIT Kharagpur are informally referred to as KGPians. Among all IITs, IIT Kharagpur has the largest campus (2,100 acres), the most departments, and the highest student enrolment. IIT Kharagpur is known for its festivals: Spring Fest (Social and Cultural Festival) and Kshitij (Techno-Management Festival). With the help of Bidhan Chandra Roy (chief minister of West Bengal), Indian educationalists Humayun Kabir and Jogendra Singh formed a committee in 1946 to consider the creation of higher technical institutions "for post-war industrial development of India." [ This was followed by the creation of a 22-member committee headed by Nalini Ranjan Sarkar. In its interim report, the Sarkar Committee recommended the establishment of higher technical institutions in India, along the lines of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and consulting from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign along with affiliated secondary institutions. The report urged that work should start with the speedy establishment of major institutions in the four-quarters of the country with the ones in the east and the west to be set up immediately. -

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India. -

Rule Section

Rule Section CO 827/2015 Shyamal Middya vs Dhirendra Nath Middya CO 542/1988 Jayadratha Adak vs Kadan Bala Adak CO 1403/2015 Sankar Narayan das vs A.K.Banerjee CO 1945/2007 Pradip kr Roy vs Jali Devi & Ors CO 2775/2012 Haripada Patra vs Jayanta Kr Patra CO 3346/1989 + CO 3408/1992 R.B.Mondal vs Syed Ali Mondal CO 1312/2007 Niranjan Sen vs Sachidra lal Saha CO 3770/2011 lily Ghose vs Paritosh Karmakar & ors CO 4244/2006 Provat kumar singha vs Afgal sk CO 2023/2006 Piar Ali Molla vs Saralabala Nath CO 2666/2005 Purnalal seal vs M/S Monindra land Building corporation ltd CO 1971/2006 Baidyanath Garain& ors vs Hafizul Fikker Ali CO 3331/2004 Gouridevi Paswan vs Rajendra Paswan CR 3596 S/1990 Bakul Rani das &ors vs Suchitra Balal Pal CO 901/1995 Jeewanlal (1929) ltd& ors vs Bank of india CO 995/2002 Susan Mantosh vs Amanda Lazaro CO 3902/2012 SK Abdul latik vs Firojuddin Mollick & ors CR 165 S/1990 State of west Bengal vs Halema Bibi & ors CO 3282/2006 Md kashim vs Sunil kr Mondal CO 3062/2011 Ajit kumar samanta vs Ranjit kumar samanta LIST OF PENDING BENCH LAWAZIMA : (F.A. SECTION) Sl. No. Case No. Cause Title Advocate’s Name 1. FA 114/2016 Union Bank of India Mr. Ranojit Chowdhury Vs Empire Pratisthan & Trading 2. FA 380/2008 Bijon Biswas Smt. Mita Bag Vs Jayanti Biswas & Anr. 3. FA 116/2016 Sarat Tewari Ms. Nibadita Karmakar Vs Swapan Kr. Tewari 4. -

West Bengal from an External Perspective Technical Session at the 4Th West Bengal Growth Workshop Indian Statistical Institute December 27, 2014, 3:30-4:30 Pm

West Bengal from an External Perspective Technical session at the 4th West Bengal Growth Workshop Indian Statistical Institute December 27, 2014, 3:30-4:30 pm Ashok K. Lahiri I am grateful to the organisers for inviting me to this session to share my thoughts on West Bengal from an external perspective. I must confess that my perspective can never be completely external since I still consider West Bengal as my ‘home’, and furthermore, even the ‘outsider’s perspective’ that I was gaining when for six years I was at the Asian Development Bank (ADB) in Manila, is fading since I returned in July 2013. Still, let me try to say a few words about the economy of West Bengal, not exclusively but with some reference to ADB’s involvement in West Bengal. In an article “A Look in the Mirror” in ‘The Outlook’ on March 31, 2014, before the recent Lok Sabha elections, Professors Maitreesh Ghatak and Sanchari Roy compared the economic performance of Gujarat under Narendra Modi with some of the best performing of the 16 major populated states of India during 1980-2010. Criteria were level and growth of per capita income, human development index, inequality, and people below the poverty line. Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Maharashtra, Punjab, and Tamil Nadu came up for special mention. Even Andhra Pradesh was mentioned for low levels of poverty, Assam for low level of inequality, Bihar for growth of per capita income, and Rajasthan for low and declining inequality. There was no mention of West Bengal. Yet, in 1980-81, in per capita income, Bengal ranked fifth after Gujarat, Haryana, Maharashtra and Punjab. -

General Elections, 1977 to the Sixth Lok Sabha

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1977 TO THE SIXTH LOK SABHA VOLUME I (NATIONAL AND STATE ABSTRACTS & DETAILED RESULTS) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI ECI-GE77-LS (VOL. I) © Election Commision of India, 1978 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without prior and express permission in writing from Election Commision of India. First published 1978 Published by Election Commision of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi - 110 001. Computer Data Processing and Laser Printing of Reports by Statistics and Information System Division, Election Commision of India. Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1977 (6th LOK SABHA) STATISCAL REPORT – VOLUME I (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 2 2. Number and Types of Constituencies 3 3. Size of Electorate 4 4. Voter Turnout and Polling Station 5 5. Number of Candidates per Constituency 6 - 7 6. Number of Candidates and Forfeiture of Deposits 8 7. Candidates Data Summary 9 - 39 8. Electors Data Summary 40 - 70 9. List of Successful Candidates 71 - 84 10. Performance of National Parties vis-à-vis Others 85 11. Seats won by Parties in States / UT’s 86 - 88 12. Seats won in States / UT’s by Parties 89 - 92 13. Votes Polled by Parties – National Summary 93 - 95 14. Votes Polled by Parties in States / UT’s 96 - 102 15. Votes Polled in States / UT by Parties 103 - 109 16. Women’s Participation in Polls 110 17. -

Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1772 — 1833)

UNIT – II SOCIAL THINKERS RAJA RAM MOHAN ROY (1772 — 1833) Introduction: Raja Ram Mohan Roy was a great socio-religious reformer. He was born in a Brahmin family on 10th May, 1772 at Radhanagar, in Hoogly district of Bengal (now West Bengal). Ramakanto Roy was his father. His mother’s name was Tarini. He was one of the key personalities of “Bengal Renaissance”. He is known as the “Father of Indian Renaissance”. He re- introduced the Vedic philosophies, particularly the Vedanta from the ancient Hindu texts of Upanishads. He made a successful attempt to modernize the Indian society. Life Raja Ram Mohan Roy was born on 22 May 1772 in an orthodox Brahman family at Radhanagar in Bengal. Ram Mohan Roy’s early education included the study of Persian and Arabic at Patna where he read the Quran, the works of Sufi mystic poets and the Arabic translation of the works of Plato and Aristotle. In Benaras, he studied Sanskrit and read Vedas and Upnishads. Returning to his village, at the age of sixteen, he wrote a rational critique of Hindu idol worship. From 1803 to 1814, he worked for East India Company as the personal diwan first of Woodforde and then of Digby. In 1814, he resigned from his job and moved to Calcutta in order to devote his life to religious, social and political reforms. In November 1930, he sailed for England to be present there to counteract the possible nullification of the Act banning Sati. Ram Mohan Roy was given the title of ‘Raja’ by the titular Mughal Emperor of Delhi, Akbar II whose grievances the former was to present 1/5 before the British king. -

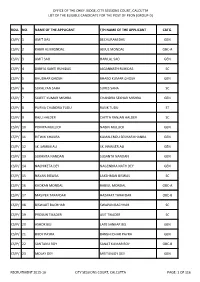

Office of the Chief Judge, City Sessions Court, Calcutta List of the Eligible Candidate for the Post of Peon (Group-D) Roll

OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUDGE, CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA LIST OF THE ELIGIBLE CANDIDATE FOR THE POST OF PEON (GROUP-D) ROLL NO. NAME OF THE APPLICANT F/H NAME OF THE APPLICANT CATG. CS/P/ 1 AMIT DAS BECHURAM DAS GEN CS/P/ 2 KABIR ALI MONDAL AJIJUL MONDAL OBC-A CS/P/ 3 AMIT SAO HARILAL SAO GEN CS/P/ 4 DIBBYA KANTI RUHIDAS JAGANNATH RUHIDAS SC CS/P/ 5 BHUDHAR GHOSH BHABO KUMAR GHOSH GEN CS/P/ 6 SUKALYAN SAHA SURES SAHA SC CS/P/ 7 SUJEET KUMAR MISHRA CHANDRA SEKHAR MISHRA GEN CS/P/ 8 PURNA CHANDRA TUDU RASIK TUDU ST CS/P/ 9 RAJU HALDER CHITTA RANJAN HALDER SC CS/P/ 10 POMPA MULLICK NABIN MULLICK GEN CS/P/ 11 RITWIK KHANRA KAMALENDU SEKHAR KHANRA GEN CS/P/ 12 SK. SAMIM ALI SK. NAWSER ALI GEN CS/P/ 13 SUKANTA NANDAN SUSANTA NANDAN GEN CS/P/ 14 NACHIKETA DEY NAGENDRA NATH DEY GEN CS/P/ 15 NAYAN BISWAS LAKSHMAN BISWAS SC CS/P/ 16 KHOKAN MONDAL RABIUL MONDAL OBC-A CS/P/ 17 MASIYER TARAFDAR HAZARAT TARAFDAR OBC-B CS/P/ 18 BISWAJIT BACHHAR SWAPAN BACHHAR SC CS/P/ 19 PROSUN TIKADER ASIT TIKADER SC CS/P/ 20 ASHOK BEJ LATE SANKAR BEJ GEN CS/P/ 21 BIJOY PAYRA BANSHI DHAR PAYRA GEN CS/P/ 22 SANTANU ROY SANAT KUMAR ROY OBC-B CS/P/ 23 MOLAY DEY MRITUNJOY DEY GEN RECRUITMENT 2015-16 CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA PAGE: 1 OF 116 OFFICE OF THE CHIEF JUDGE, CITY SESSIONS COURT, CALCUTTA LIST OF THE ELIGIBLE CANDIDATE FOR THE POST OF PEON (GROUP-D) ROLL NO. -

Civics National Civilian Awards

National Civilian Awards Bharat Ratna Bharat Ratna (Jewel of India) is the highest civilian award of the Republic of India. Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is conferred "in recognition of exceptional service/performance of the highest order", without distinction of race, occupation, position, or sex. The award was originally limited to achievements in the arts, literature, science and public services but the government expanded the criteria to include "any field of human endeavour" in December 2011. Recommendations for the Bharat Ratna are made by the Prime Minister to the President, with a maximum of three nominees being awarded per year. Recipients receive a Sanad (certificate) signed by the President and a peepal-leaf–shaped medallion. There is no monetary grant associated with the award. The first recipients of the Bharat Ratna were politician C. Rajagopalachari, scientist C. V. Raman and philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, who were honoured in 1954. Since then, the award has been bestowed on 45 individuals including 12 who were awarded posthumously. In 1966, former Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri became the first individual to be honoured posthumously. In 2013, cricketer Sachin Tendulkar, aged 40, became the youngest recipient of the award. Though usually conferred on Indian citizens, the Bharat Ratna has been awarded to one naturalised citizen, Mother Teresa in 1980, and to two non-Indians, Pakistan national Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan in 1987 and former South African President Nelson Mandela in 1990. Most recently, Indian government has announced the award to freedom fighter Madan Mohan Malaviya (posthumously) and former Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee on 24 December 2014. -

Gandhi and Bengal Politics 1920

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: F Political Science Volume 15 Issue 6 Version 1.0 Year 2015 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Gandhi and Bengal Politics 1920 - 1940 By Sudeshna Banerjee University of Burdwan, India Abstract- Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi entered nationalist politics in 1920 and changed the character of the national movement completely. Before 1920, Bengal politics was mainly dominated by the activities of the revolutionaries and the politics within Congress. Anushilan Samity and Yugantar were the two main revolutionary groups in Bengal at the beginning of twentieth century. Their main intention was to liberate their motherland through violent struggle. The Congress leaders as well as the revolutionaries of Bengal were not at all ready to accept Gandhi and his doctrine of nonviolence. Gandhi too had no sympathy for the revolutionaries, as their method was against his principle of non-violence. C R Das and Subhas Chandra Bose of Bengal Congress gave stiff opposition to Gandhi. Eventually, the death of C R Das and the imprisonment of Bose at Mandalay prison, Burma saw the emergence of Gandhiites like J M Sengupta through whom gradually the control of Bengal Congress went into the hands of Gandhi. The final showdown between Gandhi and Bose came in 1939 when Bose was compelled to resign as Congress President at Tripuri. Keywords: Swadhinata, Ahimsa, Gandhiites, Anusilan, Yugantar, Bengal provincial congress committee GJHSS-F Classification : FOR Code: 360199 GandhiandBengalPolitics19201940 Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2015. Sudeshna Banerjee. -

In the High Court at Calcutta

IN THE HIGH COURT AT CALCUTTA APPELLATE JURISDICTION SUPPLEMENTARY LIST TO THE COMBINED MONTHLY LIST OF CASES ON AND FROM , MONDAY, THE 5TH JUNE, 2017, FOR HEARING ON MONDAY, THE 5TH JUNE, 2017. INDEX SL. BENCHES COURT TIME PAGE NO. ROOM NO. NO. 1. THE HON’BLE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE NISHITA MHATRE 1 AND (DB – I) THE HON’BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY THE HON’BLE JUSTICE PATHERYA ON AND 2. AND 8 FROM THE HON’BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 05.06.2017 FROM 10.30 A.M. TILL 1.15 P.M. ON AND 3. THE HON’BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 29 FROM 05.06.2017 FROM 2.00 P.M. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- *********************************************************************** ********* 05/06/2017 COURT NO. 1 FIRST FLOOR THE HON'BLE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE NISHITA MHATRE AND HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY *********************************************************************** ********* (DB – I) ON AND FROM MONDAY, THE 10TH APRIL, 2017 - Writ Appeals relating to Service (Gr.-VI); WRIT APPEALS RELATING TO (GR.-IX) RESIDUARY; CONTEMPT SEC. 19(A), SEC. 27 OF ELECTRICITY REG. PIL, Matters under Article 226/227 of the Constitution of India relating to Tribunals under Art. 323A and applications thereto; Writ Appeals not assigned to any other bench. And On and from Monday, the 5th June 2017 to Friday, the 9th June, 2017 (Both days inclusive) – will take, in addition to their own list and determination, urgent matters relating to the list and determination of the Division Bench comprising Hon’ble Justice Sanjib Banerjee and Hon’ble Justice Siddhartha Chattopadhyay. NOTE : On and from 9.1.2017, Tribunal motions, applications and hearing will be taken up during the entire week and other matters will be taken up in the following week.