City of Rolling Hills Hazard Mitigation Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2017

Palos Verdes Peninsula Land Conservancy preserve | restore | educate | enjoy Reformation Corporation Volunteers We are pleased to share highlights of 2017 and celebrate the many results from the year’s work in land conservation on the peninsula. We are also honored to share four inspiring stories from Nan and Reed Harman, Noel Park, Anita Gash and John and Lynn Taber. These exemplary supporters show how it is possible to transform the dream of protected natural land into reality. The Conservancy continues to care for natural lands through quality habitat restoration as well as with fun, informative, nature-based outdoor programming. In 2017, Southern California’s rainfall compensated somewhat for eight years of drought. The precipitation was a welcome relief, although the resulting trail erosion and extensive weed growth Preserving land and provided additional challenges. We were delighted to install new preserve entry signage at Portuguese Bend Reserve and Alta Vicente, where ongoing restoring habitat for restoration shows great promise for supporting more wildlife. The Conservancy received a generous gift of a Toyota the education and Tundra truck to support the restoration work on the preserves. Thirteen Conservancy volunteers became certified as UC California Naturalists. Conservancy board members and staff attended the Land Trust Alliance conference to gain enjoyment of all. perspective from leaders throughout the nation on building resiliency and projecting needs for the future. We look forward to recruiting and training more walk leaders and nature center docents in the year ahead. Thank you for your contributions, which will enable us to continue the important work of preserving land and restoring habitat on the Peninsula. -

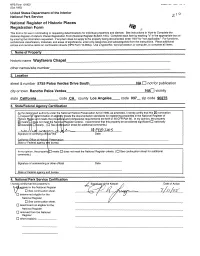

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This Form Is for Use in Nominating Or Requesting Determinations for Individual Properties and Districts

NPS Form 10-900 \M/IVIUJ i ^vy. (Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property___________________________________________________________ historic name Wayfarers Chapel ________________________________ other names/site number__________________________________________ 2. Location ___________________________ street & number 5755 Palos Verdes Drive South_______ NA d not for publication city or town Rancho Palos Verdes________________ NAD vicinity state California_______ code CA county Los Angeles. code 037_ zip code 90275 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1986, as amended, I hereby certify that this C3 nomination D request f fr*d; (termination -

Deputy Director of Public Works Public of Director Deputy

City of Rancho Palos Verdes, California Verdes, Palos Rancho of City Deputy Director of Public Works Public of Director Deputy Long- and Short-term Disability Insurance: The Compensation City pays entire premium on long-term disability Search Schedule The salary range for the Deputy Director of Public insurance at 66.6667% of monthly earnings to Works is $99,197 to $167,960. Appointment within Filing Deadline: ..................................... January 7, 2019 a maximum benefit of $10,000 per month, after the range will be dependent upon the qualifications inability to work due to injury or illness for more Preliminary Interviews: ...................January 22-24, 2019 of the selected candidate. The City of Rancho than 90 days. All employees participate in the Palos Verdes also offers the following benefits. Recommendation of Candidates: ..........January 28, 2019 State Short-Term Disability Insurance program. 9/80 Work Schedule: Full-time employees The annual premium is determined by the state Finalist Interview Process: ...................February 4, 2019 work 80 hours in 9 days and receive every and is based on an employee’s gross annual pay. other Friday off. City Hall is open Monday The premium is deducted from the employee’s pay. These dates have been confirmed, and it is recommended through Thursday from 7:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Employee Incentive Program: Employees that you plan your calendar accordingly. and on Fridays from 7:30 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. are eligible to receive annual one-time Health Insurance: Medical (2 PPOs and 3 bonuses of up to 5% of their gross annual pay HMOs), dental (PPO and HMO), and vision in recognition of exemplary performance in coverage is provided. -

Fourth Quarter, 1998

PALOS VERDES PENINSULA PEN PACES Land O S Conservancy Volume 10, Number 4 Palos Verdes Peninsula Land Conservancy Fourth Quarter, 1998 Under Development (homes) Under Development (homes) PV Drive East Crest Road RPV City Future Uncertain Hall Site Hawthorne Blvd Forrestal Property (preserved in 1996) PV Dr South Under Development Shoreline Park Under Development (homes) (Preserved in 1997) (homes) Proposed Long Point Development (hotel, homes, golf) Under Development Pacific Ocean (homes and golf) Dramatic Changes Underway on Peninsula he improving economy has struction. which would cover the old Marineland brought with it an improved Over the last ten years, some de- site, the City Hall property, and a T market for new homes. As a velopable land has been removed from portion of the open space in the new result, over the last year, dramatic play by the Conservancy. The 20- development at the end of Hawthorne changes are occurring on the Penin- acre Lunada Canyon property, the Blvd. sula. Some examples: 28.5-acre Chandler property (now the A portion of the property required • Major open space areas near Linden H. Chandler Preserve), the for the project is the City Hall site, San Pedro are being turned into homes 160-acre Forrestal property—all deeded to the City by the United States and a bluff-top golf course. could have had development, but now Department of the Interior in 1979 for • Travelers on Crest Road will are protected forever. The 53-acre “the perpetual use ...for public park notice two major developments—one Shoreline Park property, although not and public recreation area purposes.” where the Northrop buildings once developable in homes, has also been If a golf course is to be approved for stood, and another across the street. -

Beneficial Plaza and Liberty Park Historical Resources Assessment

Beneficial Plaza and Liberty Park Historical Resources Assessment Prepared for: Annette Van Duren, Save Liberty Park Los Angeles, California Prepared by: Pasadena, California February 20, 2018 Table of Contents 1. Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 1 2. Assessment Methodology. ......................................................................................................... 1 2.1 Research ............................................................................................................................ 1 2.2 Field Methods .................................................................................................................... 2 2.3 Project Team ...................................................................................................................... 2 3. Previous Evaluations and Designations ....................................................................................... 2 4. Property History ......................................................................................................................... 2 4.1 Site and Setting .................................................................................................................. 2 4.2 Architectural Description ................................................................................................... 4 4.3 Chronology of Development and Use ............................................................................... -

National Register of Historic Places 2005 Weekly Lists

National Register of Historic Places 2005 Weekly Lists January 7, 2005 ............................................................................................................................................. 3 January 14, 2005 ........................................................................................................................................... 6 January 21, 2005 ........................................................................................................................................... 9 January 28, 2005 ......................................................................................................................................... 12 February 4, 2005 ......................................................................................................................................... 16 February 11, 2005 ....................................................................................................................................... 19 February 18, 2005 ....................................................................................................................................... 22 February 25, 2005 ....................................................................................................................................... 25 March 4, 2005 ............................................................................................................................................. 28 March 11, 2005 .......................................................................................................................................... -

News Release

CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION NEWS RELEASE FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Gene Itogawa October 28, 2004 (916) 653-8936 Woodland, November 5, 2004 State Historical Resources Commission To Meet In their final meeting of the year, the State Historical Resources Commission will meet Friday, November 5 at the Yolo County Administration Building, (Erwin Meier Administrative Center), 625 Court St., Board of Supervisors Chambers, Room 206. It will consider the following nominations for the National Register of Historic Places: Avenel Cooperative Housing Project, comprised of 10 units located in Los Angeles, was designed in 1947 by Gregory Ain for a group of motion picture cartoonists and their families in the Silver Lake Area. Ain, who saw architecture as a means toward social ends, was one of several early Los Angeles Modernist architects who helped define Los Angeles as the center of the Modernist movement in American domestic architecture. Webster Schoolhouse, Markleeville, Alpine County, is a one-room schoolhouse built in 1882 and in use until 1928. It will join 11 other one-room schools in California currently listed on the National Register. Long considered the backbone of American education, the country school was attended by one-half of the country’s schoolchildren as late as 1913. Storrier-Stearns Japanese Garden in Pasadena, Los Angeles County, designed by master Japanese landscape designer Kinzuchi Fujii. Construction began in 1937 and was almost complete when Fujii was relocated to an internment camp soon after the outbreak of WWII. It is a rare extant pre-war garden still retaining its original design and many of its architectural and ornamental features. -

4.4 Cultural Resources

Zone 2 Landslide Moratorium Ordinance Revisions EIR Section 4.4 Cultural Resources 4.4 CULTURAL RESOURCES This section analyzes potential impacts to archaeological, paleontological, and historical resources. The discussion is based on the findings of a Cultural Resources Records Search Summary performed by Historical, Environmental, Archaeological, Research Team (H.E.A.R.T.) (H.E.A.R.T., April 2010) and supplemented by a paleontological study conducted by Rincon Consultants (January 2011) as well as consultation with the Gabrieleno Band of Mission Indians - Kizh Nation. The records search was conducted at the South Central Coastal Information Center (SCCIC) at California State University Fullerton, and included a historical map database search with the Geography Department at California State University Northridge, and a consultation with the Native American Heritage Commission. The paleontological resources study consists of a records review of California Geological Survey maps. To ensure the protection of known cultural resources sites identified in the study, the cultural resources report is available for review by qualified personnel at the City’s Community Development Department offices. There is no evidence to suggest the cultural or paleontological resource conditions have changed in the project area since the preparation of the 2010/2011 studies. 4.4.1 Setting a. Archaeological Overview. The overall Los Angeles region has been occupied for over 20,000 years, based on investigations in the Ballona Creek area of the Los Angeles Basin, the La Brea Tar Pits, and Malaga Cove. Chronologies for southern California indicate a generalized hunting and gathering economy in existence at a very early time. The Millingstone Period dates to over 6,000 years ago, and suggests a generalized plant collecting economy, supplemented by hunting and fishing. -

First Quarter, 2005

OPEN SPACES Volume 17, Number 1 Palos Verdes Peninsula Land Conservancy First Quarter, 2005 Jim Scharffenberger and Wayne Sharp lead fundraising efforts to preserve Portuguese Bend. PVE Councilman Jim Goodhart, Mike Gin representing LA County Supervisor Don Knabe, RHE Councilman Frank Zerunyan, RPV Mayor Larry Clark, Assemblywoman Betty Karnette, RPV Councilman Doug Stern, RPV Councilman Tom Long, Manhattan Beach Councilman Jim Aldinger, RH Mayor Tom Heinsheimer, RH Councilman Allen Lay, and PVE Mayor Dwight Abbott. Portuguese Bend Pony Club was one of 70 groups who cut ribbons at Del Conservancy Launches Cerro Park. Fundraising Campaign to Fulfill the Dream On Sunday, March 20th the Palos Verdes Peninsula Land Conservancy and the City of Rancho Palos Verdes gathered with residents and elected officials to launch a $6 million community fundraising campaign to “Fulfill the Dream” of purchasing land that will complete the 1500-acre Portuguese Bend Nature Preserve. A ribbon-cutting ceremony, hosted by Bill Ailor and RPV Mayor Larry Clark, was held at the top of Del Cerro Park, overlook- ing the magnificent slopes of Portuguese Bend with Catalina Island in the distance. This location is especially meaningful because a donor recognition site for the preserve will be created on this spectacular overlook. An estimated 500 Peninsula residents and over 70 community groups cut ribbons and showed their support for the Preserve. As part of the campaign, the Land Conservancy announced a Legacy Stakeholder program that would allow people to contribute by purchasing an honorary deed representing a portion of the preserve. Patrons who donate $37,000 or more for an honorary deed for a full acre, will be honored with permanent recognition at the Del Cerro site as a lasting tribute and legacy. -

Rancho Palos Verdes Rolling Hills Estates

November 12, 2019 |Multi-Jurisdictional Hazard Mitigation Plan Rancho Palos Verdes Rolling Hills Estates Q&A | ELEMENT A: PLANNING PROCESS | A1c. Q: Does the plan identify who represented each jurisdiction? (At a minimum, it must identify the jurisdiction represented and the person’s position or title and agency within the jurisdiction.) (Requirement §201.6(c)(1)) A: See Credits below. Credits Special Thanks Hazard Mitigation Planning Team: Agency Name Department Position City of Rancho Palos Katie Lozano Parks & Recreation Administrative Analyst II Verdes Gabriella Yap Administration Deputy City Manager Vina Ramos Finance Accounting Supervisor Administrative Analyst/ Jackie Ruiz Administration Public Safety Natalie Chan Public Works Senior Engineer So Kim Community Development Deputy Director/Planning Manager Octavio Silva Community Development Senior Planner Lukeaz Buchwald Administration IT Manager Megan Barnes Administration Border Issues Staff Liaison City of Rolling Hills Jeannie Naughton Community Development Planning Manager Estates Jessica Slawson, Planning Team, Co- Administration Administrative Analyst Chair Alexa Davis Administration Assistant City Manager Emergency Planning Carolyn J. President Consultants Harshman Acknowledgements City of Rancho Palos Verdes City of Rolling Hills Estates Jerry V. Duhovic, Mayor Judy Mitchell, Mayor John Cruikshank, Mayor Pro Tem Velveth Schmitz, Mayor Pro Tem Eric Alegria, Councilman Britt Huff, Council Member Susan M. Brooks, Councilwoman Frank Zerunyan, Council Member Ken Dyda, -

Allaback National Historic Landmark Final Report

ESSAYS ON MODERN ARCHITECTURE For the National Historic Landmark Program Introduction Chronology Essays 1. The Skyscraper 2. The Modern House 3. Modern Religious Architecture 4. The Modern College Campus and Modern Buildings on Campus 5. Modern Art Museums Architect Lists Sarah Allaback, Ph.D. Amherst, Massachusetts April 2, 2003 INTRODUCTION The following essays and lists of architects are intended to further the study of modern buildings that may qualify as National Historic Landmarks. The buildings are organized by type and evaluated in terms of architectural significance. American architects began to experiment with styles beyond the traditional neoclassical in the early nineteenth century. Styles were chosen for their historical associations and the buildings were considered architecturally pure versions of the past. By the end of the century, architects felt free to combine styles in an “eclectic” manner, without such concern for stylistic origins. New technologies and building materials encouraged this emerging experimentation. If this was all modern, however, it was certainly not “modernism.” When European modernism arrived in the United States in the 1920s no one could mistake it for anything that went before. Historians quickly labeled this early phase of modern architecture the International Style. It was short-lived. The white, geometric forms were too bleak for Americans, especially since they came without the social meaning of their European counterparts. The International Style was imported to the United States, but its early development was not without American influence. As European architects began experimenting in wild new forms of architecture, materials and forms, they studied the designs of Frank Lloyd Wright, whose work had been published in portfolios by 1910. -

Appendix A2 2018 NOP and NOP Responses

Appendix A2 2018 NOP and NOP Responses NOTICE OF PREPARATION To: Interested Persons From: City of Rancho Palos Verdes Community Development Department 30940 Hawthorne Blvd. Rancho Palos Verdes, California 90275-5391 310-544-5228 or [email protected] Subject: Notice of Preparation of an Environmental Impact Report (EIR) pursuant to the Requirements of the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) for proposed code amendments to Exception “P” of Title 15.20.040 (Landslide Moratorium Ordinance) of the Rancho Palos Verdes Municipal Code pertaining to Zone 2 The City of Rancho Palos Verdes originally prepared and circulated a Draft Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the project identified below in 2012. The purpose of this Notice of Preparation is to inform those interested that as the CEQA Lead Agency, the City of Rancho Palos Verdes will recirculate an updated Draft EIR for this project. The recirculated updated Draft EIR will cover the same environmental issue areas that were previously analyzed in the original Draft EIR circulated in 2012. However, the recirculated Draft EIR will be updated with applicable data that is new or has changed since circulation in 2012, as well as pertinent information provided in comments received on the original Draft EIR. The project description has not changed since the City originally circulated the Draft EIR in 2012. We need to know the views of you or your agency as to the scope and content of the environmental information which is germane to you or your agency’s statutory responsibilities in connection with the proposed project, particular with regards to new or updated information.