2014 Estate Planning Seminar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Representative Handbook

2410 W. Ray Rd., Suite 1 • Chandler, Arizona 85224 • 480-345-8845 • www.halaw.com Personal Representative Handbook The purpose of this handbook is to assist you in carrying out your case, whoever the decedent nominated to act as personal rep- duties as the Personal Representative (or Executor) of an estate of resentative in the Will has the right to serve. an Arizona decedent. This handbook is updated from time to time; Bear in mind, though, that just because you may have please contact us if you are not sure you have the latest version. been nominated to serve as personal representative in some- Also, please remember that this handbook is a guide; it is not in- one’s Will does not mean you have a duty to accept that nom- tended to answer every question that could come up in the admin- ination. You can always decline, in which case any alternate istration of a trust, and it is not intended to give you legal advice. candidate nominated in the Decedent’s Will would then have the opportunity to serve as personal representative. INTRODUCTION Conversely, if the Decedent died without a valid Will, the Decedent is said to have died intestate. In that case, state law What Is a Personal Representative? In Arizona, a personal (in Arizona, A.R.S. § 14-3203) controls who has the right to representative (known in many states as an executor) is the per- serve as personal representative. Roughly summarized, the son or entity appointed by the Court to administer the estate people having the right to serve as personal representative and assets of someone who has died (a decedent). -

The Personal Representative's Power to Sell Realty in Virginia

William & Mary Law Review Volume 15 (1973-1974) Issue 4 Article 8 May 1974 The Personal Representative's Power to Sell Realty in Virginia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons Repository Citation The Personal Representative's Power to Sell Realty in Virginia, 15 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 949 (1974), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol15/iss4/8 Copyright c 1974 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr COMMENT THE PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE'S POWER TO SELL REALTY IN VIRGINIA At common law, tide to personal property passed to an executor or administrator upon the death of the owner, while tide to realty vested immediately in the decedent's heirs or devisees.' During the period of administration, the personal representative's control over personalty was, and under present law remains, analogous to that of a trustee, there being few restrictions upon the power to dispose of the property for the benefit of the estate. With respect to realty, however, a personal representative at common law had neither tide nor power to sell. Two general exceptions to the common law rules have evolved to expand the personal representative's power ovex realty. First, realty may be subjected by statute to the payment of debts of the estate when the personalty is insufficient for that purpose. Second, and more sig- nificantly, an executor may sell realty when vested with such power by the will.3 This Comment will examine the development and present status in Virginia of these exceptions to the general rule against sale 'of realty by a personal representative and will suggest statutory reforms designed to bring Virginia law more in line with that in other jurisdic- tions in reflecting modem conditions. -

Last-Will-And-Testament-Template.Pdf

Last Will and Testament of ___________________________________ I, ________________________, resident in the City of ____________________, County of ____________________, State of ____________________, being of sound mind, not acting under duress or undue influence, and fully understanding the nature and extent of all my property and of this disposition thereof, do hereby make, publish, and declare this document to be my Last Will and Testament, and hereby revoke any and all other wills and codicils heretofore made by me. I. EXPENSES & TAXES I direct that all my debts, and expenses of my last illness, funeral, and burial, be paid as soon after my death as may be reasonably convenient, and I hereby authorize my Personal Representative, hereinafter appointed, to settle and discharge, in his or her absolute discretion, any claims made against my estate. I further direct that my Personal Representative shall pay out of my estate any and all estate and inheritance taxes payable by reason of my death in respect of all items included in the computation of such taxes, whether passing under this Will or otherwise. Said taxes shall be paid by my Personal Representative as if such taxes were my debts without recovery of any part of such tax payments from anyone who receives any item included in such computation. II. PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE I nominate and appoint ________________________, of ___________________________, County of ________________________, State of ______________________________ as Personal Representative of my estate and I request that (he/she) be appointed temporary Personal Representative if (he/she) applies. If my Personal Representative fails or ceases to so serve, then I nominate _____________________________of __________________________, County of ____________________________, State of ______________________ to serve. -

The New York Probate Process

THE NEW YORK PROBATE PROCESS – PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE BASICS “In Part I of this series we will discuss how a Personal Representative is appointed and take a broad look at what the position entails. In Part II, we will look as the steps you should take after being appointed the PR of an estate.” SAUL KOBRICK & ANTHONY MOCCIA NEW YORK ESTATE PLANNING ATTORNEYS SERVING NASSAU COUNTY, SUFFOLK COUNTY, AND WESTCHESTER COUNTY The death of a family member or loved one typically ushers in a period of heightened emotions and uncertainty for those impacted by the death. Regardless of how far in advance you are notified that death was inevitable, “preparing” to lose someone close to you is simply not really possible. As a result, a good deal of confusion also tends to follow a death. Adding to that confusion is the knowledge that someone must handle the legal ramifications of the decedent’s death. If a Last Will and Testament was executed by the decedent prior to death the individual appointed as Executor in the Will shall be responsible for overseeing the probate of the estate left behind by the decedent. If the decedent died intestate or without leaving behind a valid Will, the probate court will need to appoint someone to be the Personal Representative of the estate. The New York Probate Process – Personal Representative Basics www.kobricklaw.com 2 If you are appointed to be the Personal Representative, or PR, of the estate the first thing you should do is retain the services of an experienced New York estate planning attorney to provide you with advice and guidance throughout the probate process. -

Personal Representative for a Deceased Victim Victim’S Death Certificate: an Original Or Certified Copy Is Required

Documents Required When Claimant is not the Victim Documents Required by the VCF when the Claimant is not the Victim Only those authorized by law or court order may pursue a claim on behalf of another individual. In order to process a claim filed by someone other than the victim, the Special Master must first validate the individual’s authority to represent the victim for the VCF claim. Different types of documentation are required depending on the representative’s relationship to the victim. This document provides information on the types of representatives who may file a claim, and the required documents that must be submitted for the VCF to validate the individual as an authorized representative. Personal Representative for a Deceased Victim Victim’s Death Certificate: An original or certified copy is required. If possible, please submit the “long form” version of the death certificate, which lists the cause of death. Letters of Administration, Letters Testamentary, or other Court Order showing the appointment as the Personal Representative, Executor of Will, or Administrator of the Estate. A copy is sufficient for the VCF to validate the Personal Representative. An original or certified copy is required before payment can be issued. o Your court order may include limitations. Some limitations do not interfere with the VCF’s ability to validate the Personal Representative, while other limitations may impact the VCF’s ability to process the claim. See the Instructions for Letters of Administration with Limitations on the VCF website for more detailed information. o If you submit Letters of Administration, Letters Testamentary, or other Court Order that includes limitations that interfere with the VCF’s ability to process or pay your claim, you will be advised in writing and given time to obtain the appropriate documentation. -

Filing for the Administration of a Decedent’S Estate (Adm) in the District of Columbia (Valued at More Than $40,000)

FILING FOR THE ADMINISTRATION OF A DECEDENT’S ESTATE (ADM) IN THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA (VALUED AT MORE THAN $40,000) Office of the Register of Wills, Probate Division 515 5th Street, NW, Third Floor Washington, DC 20001 All attached forms and documents are available through the division’s website: http://www.dccourts.gov/dccourts/superior/probate/index.jsp May 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS General Information Forms Required to File an Estate a. Certificate of Filing Will b. Petition for Probate c. Abbreviated Probate Order d. Personal Identification Form (Form 26) e. Notice of Appointment, Notice to Creditors and Notice to Unknown Heirs f. Bond of Personal Representative Pursuant to D.C. Code, Section 20-502(a) g. Waiver of Personal Representative’s Bond h. Renunciation i. Consent to Appointment of Personal Representative Forms Required Shortly After Appointment a. General Information for Heirs, Legatees and Creditors b. Verification and Certificate of Notice General Information for Large Estates If a person died who lived in the District of Columbia, a large estate can be opened in the Probate Division of the Superior Court of the District of Columbia when the decedent owned real estate in the District of Columbia or other assets of any value or a lawsuit involving the decedent is open or needs to be opened. The assets must have been owned in just the decedent’s name; they must not have joint owners or designated beneficiaries. The forms that will be needed are located on the Probate Division website at http://www.dccourts.gov/internet/public/aud_probate/large.jsf. -

3-808. Individual Liability of Personal Representative

MRS Title 18-C, §3-808. INDIVIDUAL LIABILITY OF PERSONAL REPRESENTATIVE §3-808. Individual liability of personal representative 1. Contractual liability. Unless otherwise provided in the contract, a personal representative is not individually liable on a contract properly entered into in a fiduciary capacity in the course of administration of the estate unless the personal representative fails to reveal the representative capacity and identify the estate in the contract. [PL 2017, c. 402, Pt. A, §2 (NEW); PL 2019, c. 417, Pt. B, §14 (AFF).] 2. Liability for ownership or control of property; torts. A personal representative is individually liable for obligations arising from ownership or control of the estate or for torts committed in the course of administration of the estate only if the personal representative is personally at fault. [PL 2017, c. 402, Pt. A, §2 (NEW); PL 2019, c. 417, Pt. B, §14 (AFF).] 3. Proceedings against personal representative in fiduciary capacity. Claims based on contracts entered into by a personal representative in a fiduciary capacity, on obligations arising from ownership or control of the estate or on torts committed in the course of estate administration may be asserted against the estate by proceeding against the personal representative in a fiduciary capacity, whether or not the personal representative is individually liable. [PL 2017, c. 402, Pt. A, §2 (NEW); PL 2019, c. 417, Pt. B, §14 (AFF).] 4. Allocating liability between estate and personal representative. Issues of liability as between the estate and the personal representative individually may be determined in a proceeding for accounting, surcharge or indemnification or other appropriate proceeding. -

Crafting Donor Agreements That Withstand the Test of Time

CRAFTING DONOR AGREEMENTS THAT WITHSTAND THE TEST OF TIME ©2014 Stokes Lawrence, P.S. • What We Will Cover Today: • Problems that Arise - Case Examples • The Law • What To Include in an Agreement • How to Resolve Issues that Do Arise ©2014 Stokes Lawrence, P.S. 1 CASE LAW EXAMPLES ©2014 Stokes Lawrence, P.S. 2 Ebenezer's Old People's Home of Evangelical Ass'n of Ebenezer, N.Y. • "In the event there is an institution in the City of South Bend at the time of my death or within two years after the time of my death, which has for its purpose of its existence the maintenance of a home for old people irrespective of their religious beliefs upon at least a partial charitable basis then I desire and direct my said executor to turn all the rest and residue of the property of which I may die seized to said institution." • Ebenezer's Old People's Home of Evangelical Ass'n of Ebenezer, N.Y. v. South Bend Old People's Home, Inc., 48 N.E.2d 851, 854, 48 N.E. 2d 851 (1943) ©2014 Stokes Lawrence, P.S. 3 Ebenezer's Old People's Home of Evangelical Ass'n of Ebenezer, N.Y. • If no such institution exists in South Bend at my death or two years later, the residue is to be distributed between two homes for senior citizens and an orphanage, all identified by name, as takers in default. • After a hearing, the South Bend Old People’s Home, Inc. was selected as the recipient of the gift. -

Multiple-State Estates Under the Uniform Probate Code, 27 Wash

Washington and Lee Law Review Volume 27 | Issue 1 Article 5 Spring 3-1-1970 Multiple-State Estates Under The niU form Probate Code Allan D. Vestal Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr Part of the Estates and Trusts Commons Recommended Citation Allan D. Vestal, Multiple-State Estates Under The Uniform Probate Code, 27 Wash. & Lee L. Rev. 70 (1970), https://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol27/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Washington and Lee Law Review at Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington and Lee Law Review by an authorized editor of Washington & Lee University School of Law Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 70 WASHINGTON AND LEE LAW REVIEW [Vol. XXVII MULTIPLE-STATE ESTATES UNDER THE UNIFORM PROBATE CODE ALLAN D. VESTAL* I. THE UNIFORM PROBATE CODE On August 7, 1969, the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws adopted by a vote of the states the Uniform Pro- bate Code. The following week the House of Delegates of the American Bar Association approved the Code.' In these actions a giant step forward was taken toward uniformity in probate law in the United States. Although no state has had the opportunity to consider and adopt the Uniform Code, there is reason to believe that a number of states will give serious consideration to the Code in the near future. For some time in the post World War II period various segments of the legal profession and the lay public had been dissatisfied with the methods of passing property from one generation to another.2 This had resulted in a number of probate revisions which have taken place or which have been urged.3 In the decade of the sixties impetus for re- *John F. -

Minnesota Statutes 1975 Supplement

MINNESOTA STATUTES 1975 SUPPLEMENT UNIFORM PROBATE CODE 524.1-102 CHAPTER 524. UNIFORM PROBATE CODE Sec. Sec. 524.1-102 Purposes; rule of construction. 524.3-401 Formal testacy proceedings; nature; 524.1-105 Repealed. when commenced. 524.1-107 Evidence as to death or status. 524.3-402 Formal testacy or appointment pro 524.1-108 Acts by holder of general power. ceedings; petition; contents. 524.1-201 General definitions. 524.3-403 Formal testacy proceeding; notice of 524.1-301 Territorial application. hearing on petition. 524.1-302 Subject matter jurisdiction. 524.3-406 Formal testacy proceedings; con 524.1-303 Venue; multiple proceedings; trans tested cases; testimony of attesting witnesses. fer. 524.3-409 Formal testacy proceedings; order; 524.1-304 Repealed. foreign will. 524.1-305 Repealed. 524.3-412 Formal testacy proceedings; effect of 524.1-307 Registrar; powers. order; vacation. 524.1-401 Notice; method and time of giving. 524.3-413 Formal testacy proceedings; vacation 524.1-403 Pleadings; when parties bound by of order for other cause and modification of others; notice. orders, judgments, and decrees. 524.2-110 Advancements. [New] 524.3-502 Supervised administration; petition; 524.2-501 Who may make a will. [New] order. 524.2-502 Execution. [New] 524.3-601 Qualification. 524.2-504 Self-proved will. [New] 524.3-602 Acceptance of appointment; consent 524.2-505 Who may witness. [New] to jurisdiction. 524.2-506 Choice of law as to execution. [New] 524.3-603 Bond not required without court or 524.2-507 Revocation by writing or by act. -

ADMINISTRATION of INTESTATE ESTATES I. GENERAL Filed In

ADMINISTRATION OF INTESTATE ESTATES I. GENERAL Filed in Probate Court § 43-2-1 All letters testamentary or of administration, general or special, and the bonds given by executors and administrators must be recorded by the Judge of Probate. II. PETITION FOR LETTERS OF ADMINISTRATION A. Place of filing § 43-2-40 1. County where decedent was an inhabitant at the time of death 2. County where non-resident decedent leaves assets 3. County where non-resident decedent’s assets are brought after death 4. Any county in Alabama where the decedent is a resident and leaves assets; if decedent leaves no assets in county of residence, then after 3 months from death B. Priority of Grant of Letters of Administration § 43-2-42 1. Spouse 2. Next of kin 3. Largest creditor 4. County or General Administrator - for those counties with population of 400,000 or more 5. Such person as Probate Judge appoints C. Disqualification of persons to serve as Administrator 1. Under the age of 19 2. Convicted of an infamous crime 3. Incompetent due to intemperance, improvidence or lack of understanding 4. Non-resident of the State of Alabama unless serving as administrator in another state, territory, or jurisdiction D. Time for Administration 1. Letters are not to be granted for 5 days after death § 43-2-45 2. The spouse, next of kin and largest creditor must file for letters within 40 days or they are deemed to waive their priority to administer estate. § 43- 2-43 3. In counties with County or General Administrators, a renunciation by the County or General Administrator may be required to be filed before letters will issue. -

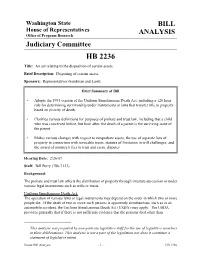

HB 2236 Title: an Act Relating to the Disposition of Certain Assets

Washington State BILL House of Representatives ANALYSIS Office of Program Research Judiciary Committee HB 2236 Title: An act relating to the disposition of certain assets. Brief Description: Disposing of certain assets. Sponsors: Representatives Goodman and Lantz. Brief Summary of Bill • Adopts the 1991 version of the Uniform Simultaneous Death Act, including a 120 hour rule for determining survivorship under instruments or laws that transfer title to property based on priority of death. • Clarifies various definitions for purposes of probate and trust law, including that a child who was conceived before, but born after, the death of a parent is the surviving issue of the parent. • Makes various changes with respect to nonprobate assets, the use of separate lists of property in connection with revocable trusts, statutes of limitation in will challenges, and the award of attorney's fees in trust and estate disputes. Hearing Date: 2/26/07 Staff: Bill Perry (786-7123). Background: The probate and trust law affects the distribution of property through intestate succession or under various legal instruments such as wills or trusts. Uniform Simultaneous Death Act. The operation of various laws or legal instruments may depend on the order in which two or more people die. If the death of two or more such persons is apparently simultaneous, such as in an automobile accident, the Uniform Simultaneous Death Act (USDA) may apply. The USDA provides generally that if there is not sufficient evidence that the persons died other than This analysis was prepared by non-partisan legislative staff for the use of legislative members in their deliberations.