Idescat. SORT. Improving Small Area Estimation by Combining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visualizing Research Collaboration in Statistical Science: a Scientometric

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal) Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 9-13-2019 Visualizing Research Collaboration in Statistical Science: A Scientometric Perspective Prabir Kumar Das Library, Documentation & Information Science Division, Indian Statistical Institute, 203 B T Road, Kolkata - 700108, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Das, Prabir Kumar, "Visualizing Research Collaboration in Statistical Science: A Scientometric Perspective" (2019). Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal). 3039. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/3039 Viisualliiziing Research Collllaborattiion iin Sttattiisttiicall Sciience:: A Sciienttomettriic Perspecttiive Prrabiirr Kumarr Das Sciienttiiffiic Assssiissttantt – A Liibrrarry,, Documenttattiion & IInfforrmattiion Sciience Diiviisiion,, IIndiian Sttattiisttiicall IInsttiittutte,, 203,, B.. T.. Road,, Kollkatta – 700108,, IIndiia,, Emaiill:: [email protected] Abstract Using Sankhyā – The Indian Journal of Statistics as a case, present study aims to identify scholarly collaboration pattern of statistical science based on research articles appeared during 2008 to 2017. This is an attempt to visualize and quantify statistical science research collaboration in multiple dimensions by exploring the co-authorship data. It investigates chronological variations of collaboration pattern, nodes and links established among the affiliated institutions and countries of all contributing authors. The study also examines the impact of research collaboration on citation scores. Findings reveal steady influx of statistical publications with clear tendency towards collaborative ventures, of which double-authored publications dominate. Small team of 2 to 3 authors is responsible for production of majority of collaborative research, whereas mega-authored communications are quite low. -

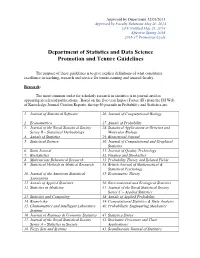

Department of Statistics and Data Science Promotion and Tenure Guidelines

Approved by Department 12/05/2013 Approved by Faculty Relations May 20, 2014 UFF Notified May 21, 2014 Effective Spring 2016 2016-17 Promotion Cycle Department of Statistics and Data Science Promotion and Tenure Guidelines The purpose of these guidelines is to give explicit definitions of what constitutes excellence in teaching, research and service for tenure-earning and tenured faculty. Research: The most common outlet for scholarly research in statistics is in journal articles appearing in refereed publications. Based on the five-year Impact Factor (IF) from the ISI Web of Knowledge Journal Citation Reports, the top 50 journals in Probability and Statistics are: 1. Journal of Statistical Software 26. Journal of Computational Biology 2. Econometrica 27. Annals of Probability 3. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 28. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Series B – Statistical Methodology Molecular Biology 4. Annals of Statistics 29. Biometrical Journal 5. Statistical Science 30. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 6. Stata Journal 31. Journal of Quality Technology 7. Biostatistics 32. Finance and Stochastics 8. Multivariate Behavioral Research 33. Probability Theory and Related Fields 9. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 34. British Journal of Mathematical & Statistical Psychology 10. Journal of the American Statistical 35. Econometric Theory Association 11. Annals of Applied Statistics 36. Environmental and Ecological Statistics 12. Statistics in Medicine 37. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C – Applied Statistics 13. Statistics and Computing 38. Annals of Applied Probability 14. Biometrika 39. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 15. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory 40. Probabilistic Engineering Mechanics Systems 16. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 41. -

Rank Full Journal Title Journal Impact Factor 1 Journal of Statistical

Journal Data Filtered By: Selected JCR Year: 2019 Selected Editions: SCIE Selected Categories: 'STATISTICS & PROBABILITY' Selected Category Scheme: WoS Rank Full Journal Title Journal Impact Eigenfactor Total Cites Factor Score Journal of Statistical Software 1 25,372 13.642 0.053040 Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application 2 515 5.095 0.004250 ECONOMETRICA 3 35,846 3.992 0.040750 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION 4 36,843 3.989 0.032370 JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL STATISTICAL SOCIETY SERIES B-STATISTICAL METHODOLOGY 5 25,492 3.965 0.018040 STATISTICAL SCIENCE 6 6,545 3.583 0.007500 R Journal 7 1,811 3.312 0.007320 FUZZY SETS AND SYSTEMS 8 17,605 3.305 0.008740 BIOSTATISTICS 9 4,048 3.098 0.006780 STATISTICS AND COMPUTING 10 4,519 3.035 0.011050 IEEE-ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 11 3,542 3.015 0.006930 JOURNAL OF BUSINESS & ECONOMIC STATISTICS 12 5,921 2.935 0.008680 CHEMOMETRICS AND INTELLIGENT LABORATORY SYSTEMS 13 9,421 2.895 0.007790 MULTIVARIATE BEHAVIORAL RESEARCH 14 7,112 2.750 0.007880 INTERNATIONAL STATISTICAL REVIEW 15 1,807 2.740 0.002560 Bayesian Analysis 16 2,000 2.696 0.006600 ANNALS OF STATISTICS 17 21,466 2.650 0.027080 PROBABILISTIC ENGINEERING MECHANICS 18 2,689 2.411 0.002430 BRITISH JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICAL & STATISTICAL PSYCHOLOGY 19 1,965 2.388 0.003480 ANNALS OF PROBABILITY 20 5,892 2.377 0.017230 STOCHASTIC ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH AND RISK ASSESSMENT 21 4,272 2.351 0.006810 JOURNAL OF COMPUTATIONAL AND GRAPHICAL STATISTICS 22 4,369 2.319 0.008900 STATISTICAL METHODS IN -

Abbreviations of Names of Serials

Abbreviations of Names of Serials This list gives the form of references used in Mathematical Reviews (MR). ∗ not previously listed The abbreviation is followed by the complete title, the place of publication x journal indexed cover-to-cover and other pertinent information. y monographic series Update date: January 30, 2018 4OR 4OR. A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research. Springer, Berlin. ISSN xActa Math. Appl. Sin. Engl. Ser. Acta Mathematicae Applicatae Sinica. English 1619-4500. Series. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 0168-9673. y 30o Col´oq.Bras. Mat. 30o Col´oquioBrasileiro de Matem´atica. [30th Brazilian xActa Math. Hungar. Acta Mathematica Hungarica. Akad. Kiad´o,Budapest. Mathematics Colloquium] Inst. Nac. Mat. Pura Apl. (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro. ISSN 0236-5294. y Aastaraam. Eesti Mat. Selts Aastaraamat. Eesti Matemaatika Selts. [Annual. xActa Math. Sci. Ser. A Chin. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series A. Shuxue Estonian Mathematical Society] Eesti Mat. Selts, Tartu. ISSN 1406-4316. Wuli Xuebao. Chinese Edition. Kexue Chubanshe (Science Press), Beijing. ISSN y Abel Symp. Abel Symposia. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 2193-2808. 1003-3998. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. G¨ottingenNeue Folge Abhandlungen der Akademie der xActa Math. Sci. Ser. B Engl. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series B. English Wissenschaften zu G¨ottingen.Neue Folge. [Papers of the Academy of Sciences Edition. Sci. Press Beijing, Beijing. ISSN 0252-9602. in G¨ottingen.New Series] De Gruyter/Akademie Forschung, Berlin. ISSN 0930- xActa Math. Sin. (Engl. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica (English Series). 4304. Springer, Berlin. ISSN 1439-8516. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. Hamburg Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften xActa Math. Sinica (Chin. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica. -

The Importance of Endogenous Peer Group Formation

Econometrica, Vol. 81, No. 3 (May, 2013), 855–882 FROM NATURAL VARIATION TO OPTIMAL POLICY? THE IMPORTANCE OF ENDOGENOUS PEER GROUP FORMATION BY SCOTT E. CARRELL,BRUCE I. SACERDOTE, AND JAMES E. WEST1 We take cohorts of entering freshmen at the United States Air Force Academy and assign half to peer groups designed to maximize the academic performance of the low- est ability students. Our assignment algorithm uses nonlinear peer effects estimates from the historical pre-treatment data, in which students were randomly assigned to peer groups. We find a negative and significant treatment effect for the students we in- tended to help. We provide evidence that within our “optimally” designed peer groups, students avoided the peers with whom we intended them to interact and instead formed more homogeneous subgroups. These results illustrate how policies that manipulate peer groups for a desired social outcome can be confounded by changes in the endoge- nous patterns of social interactions within the group. KEYWORDS: Peer effects, social network formation, homophily. 0. INTRODUCTION PEER EFFECTS HAVE BEEN widely studied in the economics literature due to the perceived importance peers play in workplace, educational, and behavioral outcomes. Previous studies in the economics literature have focused almost ex- clusively on the identification of peer effects and have only hinted at the poten- tial policy implications of the results.2 Recent econometric studies on assorta- tive matching by Graham, Imbens, and Ridder (2009) and Bhattacharya (2009) have theorized that individuals could be sorted into peer groups to maximize productivity.3 This study takes a first step in determining whether student academic per- formance can be improved through the systematic sorting of students into peer groups. -

V1603419 Discriminant Analysis When the Initial

TECHNOMETRICSO, VOL. 16, NO. 3, AUGUST 1974 Discriminant Analysis When the Initial Samples are Misclassified II: Non-Random Misclassification Models Peter A. Lachenbruch Department of Biostatistics, University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, North Carolina Two models of non-random initial misclassifications are studied. In these models, observations which are closer to the mean of the “wrong” population have a greater chance of being misclassified than others. Sampling st,udies show that (a) the actual error rates of the rules from samples with initial misclassification are only slightly affected; (b) the apparent error rates, obtained by resubstituting the observations into the calculated discriminant function, are drastically affected, and cannot be used; and (c) the Mahalanobis 02 is greatly inflated. KEYWORDS misclassified. This clearly is unrealistic. The present Discriminant Analysis study attempts to present two other models which Robustness Non-Random Initial Misclassification it is hoped are more realistic than the “equal chance” model. To do this, we sacrifice some mathematical rigor, as the equations involved are 1. INTR~DUOTI~N very difficult to set down. Thus, Monte Carlo Lachenbruch (1966) studied the effects of mis- experiments are used to evaluat’e the behavior of classification of the initial samples on the per- the LDF. formance of the linear discriminant function (LDF). 2. hlODELSAND EXPERIMENTS More recently, Mclachlan (1972) developed the asymptotic results for this model and found gen- We assume that observations x, from the ith erally good agreement with the earlier results. It population, 7~; , i = 1, 2 are normally distributed was found that if the total proportion was not with mean p, and covariance matrix I. -

Chiu-Hsieh (Paul) Hsu

Curriculum Vitae Dr. Chiu-Hsieh (Paul) Hsu Contact Information Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health [email protected] University of Arizona (520) 626-5054 1295 N Martin Ave. Drachman Hall A232 Tucson, AZ 85724 EDUCATION 1997 M.S. in Statistics, National Tsing Hua University, Hsinchu, Taiwan Advisor: Professor Anne Chao. Thesis: “Under Random Effect Models, Inference for Capture-Recapture When Time, Behavioral Response, and Heterogeneity Affect Capture Probabilities” 2000 M.S. in Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 2003 Ph.D. in Biostatistics, School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Advisor: Professor Jeremy M. G. Taylor. Thesis: “Survival Analysis via Nonparametric Multiple Imputation” EMPLOYMENT AND APPOINTMENTS 1996-1998 Research & Teaching Assistant, Department of Statistics, National Tsing Hua University, HsinChu, Taiwan 1998-1999 Teaching Assistant, Biostatistics Department, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 1999-2003 Research Assistant, Biostatistics Department, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 2003-2005 Assistant Professor (NTE), Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health (MEZCOPH), University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 2005-2011 Assistant Professor (TE), Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health (MEZCOPH), University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 2011-2017 Associate Professor, Mel and Enid Zuckerman College of Public Health (MEZCOPH), University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona 2013- Assistant Director for Biostatistics, Phase I & II Consortium, -

^^.^-3 Causal Diagrams for Empirical Research C^-J-H Di^^I^)

^^. ^-3 Biometrika (1995), 82,4, pp. 669-710 Printed in Great Britain Causal diagrams for empirical research C^-j-h di^^i^) BY JUDEA PEARL Cognitive Systems Laboratory, Computer Science Department, University of California, Los Angeles, California 90024, U.S.A. SUMMARY The primary aim of this paper is to show how graphical models can be used as a mathematical language for integrating statistical and subject-matter information. In par- ticular, the paper develops a principled, nonparametric framework for causal inference, in which diagrams are queried to determine if the assumptions available are sufficient for identifying causal effects from nonexperimental data. If so the diagrams can be queried to produce mathematical expressions for causal effects in terms of observed distributions; otherwise, the diagrams can be queried to suggest additional observations or auxiliary experiments from which the desired inferences can be obtained. Some key words: Causal inference; Graph model; Structural equations; Treatment effect. 1. INTRODUCTION The tools introduced in this paper are aimed at helping researchers communicate quali- tative assumptions about cause-effect relationships, elucidate the ramifications of such assumptions, and derive causal inferences from a combination of assumptions, experi- ments, and data. The basic philosophy of the proposed method can best be illustrated through the classi- cal example due to Cochran (Wainer, 1989). Consider an experiment in which soil fumi- gants, X, are used to increase oat crop yields, Y, by controlling the eelworm population, Z, but may also have direct effects, both beneficial and adverse, on yields beside the control of eelworms. We wish to assess the total effect of the fumigants on yields when this study is complicated by several factors. -

Biosrhythms Department of Biostatistics | Gillings School of Global Public Health | the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in This Issue

Issue No. 27 December 2015 BiosRhythms Department of Biostatistics | Gillings School of Global Public Health | The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill In this issue 3 Message from the chair 4 BIOS students prove excellence with national awards - again! 5 Students publish in top journals 6 Q&A: Outgoing JASA editor Joseph Ibrahim Biostatistics faculty members honored at international 7 conference 8 Checking in with BIOS alumni 9 Chen receives 2015 James E. Grizzle alumni award 10 CSCC’s Dental Toolkit improves data management CSRL studies tobacco communication among high-risk 11 populations 12 2015 awards, honors and grants 13 Save the date in 2016 14 Your generosity has global impact 2 Message from the Chair I want to begin by thanking all of you, the creative and accomplished faculty, staff, students, alumni and friends, who are a part of our thriving and successful Department of Biostatistics. This past year has been outstanding, and we have experienced many successes in research, teaching, mentoring, placement of graduates and other dimensions. The 2015 Bernard G. Greenberg Distinguished Lecture Series was held on May 11-12. This year’s speaker and award recipient was Susan A. Murphy, PhD, H.E. Robbins Michael R. Kosorok, PhD Distinguished University Professor of statistics and professor of psychiatry at the University of Michigan. Dr. Murphy received her doctorate in statistics from W.R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished UNC-Chapel Hill. She was named a John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Fellow for her work in developing the Sequential Multiple Assignment Professor and Chair Randomized Trial, or SMART. -

Statistics Promotion and Tenure Guidelines

Approved by Department 12/05/2013 Approved by Faculty Relations May 20, 2014 UFF Notified May 21, 2014 Effective Spring 2016 2016-17 Promotion Cycle Department of Statistics Promotion and Tenure Guidelines The purpose of these guidelines is to give explicit definitions of what constitutes excellence in teaching, research and service for tenure-earning and tenured faculty. Research: The most common outlet for scholarly research in statistics is in journal articles appearing in refereed publications. Based on the five-year Impact Factor (IF) from the ISI Web of Knowledge Journal Citation Reports, the top 50 journals in Probability and Statistics are: 1. Journal of Statistical Software 26. Journal of Computational Biology 2. Econometrica 27. Annals of Probability 3. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 28. Statistical Applications in Genetics and Series B – Statistical Methodology Molecular Biology 4. Annals of Statistics 29. Biometrical Journal 5. Statistical Science 30. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 6. Stata Journal 31. Journal of Quality Technology 7. Biostatistics 32. Finance and Stochastics 8. Multivariate Behavioral Research 33. Probability Theory and Related Fields 9. Statistical Methods in Medical Research 34. British Journal of Mathematical & Statistical Psychology 10. Journal of the American Statistical 35. Econometric Theory Association 11. Annals of Applied Statistics 36. Environmental and Ecological Statistics 12. Statistics in Medicine 37. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series C – Applied Statistics 13. Statistics and Computing 38. Annals of Applied Probability 14. Biometrika 39. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis 15. Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory 40. Probabilistic Engineering Mechanics Systems 16. Journal of Business & Economic Statistics 41. Statistica Sinica 17. -

Statistics Discipline Assessment Report 2013 Statistics Discipline

University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well Assessment of Student Learning Reports Assessment of Student Learning Committee Fall 2013 Statistics Discipline Assessment Report 2013 Statistics Discipline Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/aslc_reports Recommended Citation Statistics Discipline, "Statistics Discipline Assessment Report 2013" (2013). Assessment of Student Learning Reports. 298. https://digitalcommons.morris.umn.edu/aslc_reports/298 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Assessment of Student Learning Committee at University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. It has been accepted for inclusion in Assessment of Student Learning Reports by an authorized administrator of University of Minnesota Morris Digital Well. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATISTICS UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA MORRIS STUDENT LEARNING OJECTIVES AND OUTCOMES: STATISTICS DISCIPLINE PREPARED BY: ENGIN SUNGUR, PROFESSOR OF STATISTICS JON ANDERSON, PROFESSOR OF STATISTICS JONG-MIN KIM, ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF STATISTICS FALL 2013 STATISTICS DISCIPLINE ASL-2012-2013 1 Phase I. UNIT MISSION/GOAL(S) Please state your unit’s mission/goal(s): To advance the knowledge of statistics: by teaching statistics and processes, by research in statistics and statistical pedagogy, and by dissemination of this knowledge to our students and the community we serve. Please describe how your unit mission/goal(s) relate to the institutional mission The study of statistics is central to the liberal arts education. The statistics curriculum serves as an integral part of students’ active pursuit of liberal arts education. The discipline’s mission concentrates on the three main components of the institutional mission, namely, teaching, research, and outreach. -

Copyright © 2017 Thomson Reuters

جامعة الجوف عمادة شؤون المكتبات Journal Citation Report @ LIST OF TOP JOURNAL TITLE BASED ON IMPACT FACTOR COLLEGE OF SCIENCES SUBJECT CATEGORY : STATISTICS AND PROBABILITY JCR Data 2015 Full Journal Title Rank JCR Abbreviated Title ISSN Journal Impact 5-Year Impact (linked to journal information) Total Cites Factor Factor 1 STATISTICAL METHODS IN MEDICAL RESEARCH STAT METHODS MED RES 0962-2802 2,703 4.634 4.247 JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL STATISTICAL SOCIETY SERIES B-STATISTICAL 2 J R STAT SOC B 1369-7412 17,404 4.222 7.278 METHODOLOGY 3 ECONOMETRICA ECONOMETRICA 0012-9682 24,957 4.053 5.399 4 BRITISH JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICAL & STATISTICAL PSYCHOLOGY BRIT J MATH STAT PSY 0007-1102 1,278 3.698 2.739 5 Annual Review of Statistics and Its Application ANNU REV STAT APPL 2326-8298 74 3.045 3.045 6 ANNALS OF STATISTICS ANN STAT 0090-5364 15,680 2.780 3.921 7 Journal of Statistical Software J STAT SOFTW 1548-7660 6,868 2.379 9.066 8 STOCHASTIC ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH AND RISK ASSESSMENT STOCH ENV RES RISK A 1436-3240 2,297 2.237 2.426 9 CHEMOMETRICS AND INTELLIGENT LABORATORY SYSTEMS CHEMOMETR INTELL LAB 0169-7439 6,431 2.217 2.595 10 STATISTICAL SCIENCE STAT SCI 0883-4237 4,346 2.213 3.716 11 PROBABILITY THEORY AND RELATED FIELDS PROBAB THEORY REL 0178-8051 2,933 2.204 2.100 12 FINANCE AND STOCHASTICS FINANC STOCH 0949-2984 1,014 2.169 2.043 13 BIOSTATISTICS BIOSTATISTICS 1465-4644 3,136 2.109 2.543 14 FUZZY SETS AND SYSTEMS FUZZY SET SYST 0165-0114 13,316 2.098 2.376 15 JOURNAL OF CHEMOMETRICS J CHEMOMETR 0886-9383 3,193 1.873 2.227 16 Econometric