Measurements in the Straits of Dover, and Their Relation to the Netherlands Caosts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Archaeological Evaluation of Wetlands

98084_Report_Cover_2A_outline 16/6/06 11:38 am Page 1 Report prepared by Lis Dyson, Ellen Heppell, Casper Johnson and Marnix Pieters with Cecile Baeteman, Jan Bastiaens, Katrien Cousserier, Koen Deforce, Isabel Jansen, Erwin Meylemans, Liesbet Schietecatte, Liesbeth Theunissen, Robert van Heeringen, Johan van Laecke and Inge Zeebroek This project has received European Regional Development Funding through the INTERREG IIIB Community initiative 98084_Report_Cover_2A_outline 16/6/06 11:38 am Page 2 © The authors and Kent County Council on behalf of the Planarch Partnership. Maidstone 2006 ISBN 1 901509 75 3 98084_Report_Cover_2A_outline 16/6/06 11:38 am Page 3 Report prepared by Lis Dyson, Casper Johnson (Kent County Council), Ellen Heppell (Essex County Council), and Marnix Pieters (VIOE) with Cecile Baeteman, (Koninklijk Belgisch Instituut voor Natuurwetenschappen), Liesbeth Theunissen, Robert van Heeringen (ROB), Katrien Cousserier, Isabel Jansen (CAI), Koen Deforce, Jan Bastiaens, Erwin Meylemans, Liesbet Schietecatte, Johan van Laecke and Inge Zeebroek (VIOE) May 2006 © The authors and Kent County Council on behalf of the Planarch partners Maidstone 2006 ISBN 1 901509 761 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY…………………………………………………………….………..….i 1. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………………..…..1 2. WETLAND MAP FOR NWE by K. Cousserier ………………………………………………13 3. PLANARCH 2 PILOT STUDIES 3.1 THE STUMBLE, ESSEX by E. Heppell………………………………………………23 3.2 THE BELGIAN POLDERS, FLANDERS: A TEST CASE 2002-2006 by M. Pieters, L. Schietecatte, I. Zeebroek, E. Meylemans, I. Jansen & J. van Laecke…………………………………………………………………………39 3.3 KENT by L. Dyson ……………………………………………………………………..55 3.4 THE THREAT OF DESICCATION - RECENT WORK ON THE IN SITU MONITORING OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL WETLAND SITES IN THE NETHERLANDS by R.M. van Heeringen & E.M. -

British Birds |

VOL. XLVIII JULY No. 7 1955 BRITISH BIRDS DO ENGLISH WOODPIGEONS MIGRATE ? By DAVID LACK (Edward Grey Institute, Oxford) and M. G. RIDPATH (Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, Tolworth) INTRODUCTION THE object of this short paper is to draw attention to a curious problem in the hope that others will help in solving it. The obser vations here described, made independently by Lack round Oxford and by Ridpath in Kent and Sussex, cannot be satisfactorily interpreted until more is known from other parts of England. At first, each of us supposed that we had chanced on a big autumn migration of Woodpigeons (Cohimba palumbus), but now we are doubtful. The earlier literature on the migration of Woodpigeons was reviewed by Alexander (1940) and re-summarized by Snow (1953). So far as England is concerned the evidence was conflicting. In the autumn, there might be an arrival from Scandinavia into East Anglia and from north-western France into S.E. England, while a S.W. movement was seen for many years in the Stour valley, Worcestershire. That is all, and as yet it is quite uncertain whether the apparent increase in Woodpigeons in southern England in autumn is due to purely local aggregation or to migration and, if to migration, whether this comes from northern Britain, Scandi navia or France. OBSERVATIONS ROUND OXFORD (D. LACK) In 1953, during an autumn watch for visible migration on Boars Hill, just outside Oxford, big flights of Woodpigeons were noted going south in the early mornings during the last few days of October. At first they were dismissed as feeding movements from a roost, but over 400 individuals passed on 30th October and they flew high like migrants. -

South Foreland Lighthouse Access Statement

South Foreland Lighthouse Access Statement The Front, St Margaret’s Bay, Dover, Kent, CT15 6HP T: 01304 853281 E: [email protected] Introduction 1. The lighthouse is situated on the iconic White Cliffs of Dover 2 miles from the White Cliffs Visitor Centre. The grounds are grassed with a pebble driveway. 2. There is limited mobile phone reception at the property 3. Assistance dogs are welcome throughout and water is provided outside the lighthouse and in the tearoom courtyard 4. Access to the lighthouse tower can be challenging with 73 stairs to the top some of which are narrow and difficult to climb 5. We recommend that all visitors with access needs call ahead to discuss their visit with a member of staff Arrival & Parking Facilities 1. On-site parking is only available to disabled visitors if booked in advance. All other visitors park at the White Cliffs of Dover and walk to site following the waymarked footpath (2 miles). 2. Visitors who have arranged to park in the grounds park on the grass near the lighthouse tower. This area is sloping and can be muddy and uneven. Disabled visitors can be dropped off closer to the tower or tearoom if arranged in advance. 3. The paths around the lighthouse are made of 25mm stones which are challenging when using a wheelchair. WCs 1. There is an accessible toilet in the main toilet block with wider doors 2. Both the main door and the toilet door are manually operated 3. The bathroom is 2m x 1.8m with a 410mm high toilet with left hand transfer. -

Beach Sustainability and Biodiversity on Eastern Channel Coasts

Beach Sustainability and Biodiversity on Eastern Channel Coasts Interim Report of the Beaches At Risk (BAR) Project January 2005 BAR: BEACHES AT RISK Beaches at Risk is a partnership project part funded by the European Union Regional Development Fund, under the INTERREG III programme. The principal partners are: University of Sussex East Sussex County Council Université de Rouen in association with the Université de Caen Université du Littoral, Dunkerque For further information visit the project web site at www.geog.sussex.ac.uk/BAR or contact the BAR Project Leader Dr Cherith Moses, Department of Geography, University of Sussex, Falmer, Brighton, East Sussex BN1 9QJ. Phone +44 (0)1273 877037. Fax. +44 (0)1273 677196. E-mail [email protected]. Interim Report of the Beaches At Risk (BAR) Project BEACH SUSTAINABILITY AND BIODIVERSITY ON EASTERN CHANNEL COASTS English project team: University of Sussex, Department of Geography Executive team: Dr Cherith Moses (Overall Project Leader) Dr David Robinson Dr Rendel Williams (Deputy Project Leader) Research team: Dr Uwe Dornbusch Jerome Curoy Faye Gillespie Elinor Low Tamsin Watt East Sussex County Council, Environment Group Ecology team: Dr Kate Cole Dr Alex Tait (Deputy Project Leader) Tracey Younghusband Organisations supporting the project through match funding: Brighton and Hove City Council Environment Agency Pevensey Coastal Defence Ltd. Posford Haskoning Ltd. Associated organisations: English Nature, Hastings Borough Council, Kent County Council, Lewes District Council, National -

Cultura E Civiltà the White Cliffs of Dover Trascrizione the White Cliffs of Dover Form Part of the Coastline of England Facing

Cultura e Civiltà The White Cliffs of Dover Trascrizione The White Cliffs of Dover form part of the coastline of England facing France. The cliffs are as high as 350 feet in some places. They have a striking appearance because the cliff face is made of chalk with streaks of black flint. Thousands of years ago, the whole area was under the sea. Lots of very small sea creatures died and over the years their bones and shells were pressed together and became chalk. They gradually rose up, becoming white cliffs. Erosion from the seawater keeps the cliffs white and where the sea cannot reach them, they are covered by vegetation. The White Cliffs of Dover are often considered a symbol of England because they are the last sight that travelers see when they leave England, and the first thing they see when they arrive. In fact, at the point where they rise, England is only 21 miles from the French coast. These cliffs were an important part of the defenses of Britain during both World Wars. However, their importance goes much farther back in history. The White Cliffs of Dover stood tall through several invasion attempts, from Julius Caesar in 55 BC to Hitler’s Nazis in 1940. Under the Romans, the Cliffs were used as the base for a lighthouse. In the Middle Ages, Dover Castle, nicknamed ‘The Key to England’ because of its strategic location, was built there. It is the largest castle in England. During the Napoleonic Wars, prisoners of the castle carved secret tunnels under the Cliffs, which Winston Churchill later used as his World War II headquarters. -

Filming at the White Cliffs of Dover & South Foreland Lighthouse

Filming at the White Cliffs of Dover & South Foreland Lighthouse The White Cliffs of Dover office, 1 Centenary Cottages, Langdon Cliffs, Upper Road, Dover, Kent – CT16 1HJ. Sat-Nav CT15 5NA Call our dedicated filming and locations office on 020 7824 7128 or 020 7824 7129 • The filming & locations office issue filming contracts, check insurance and set fees. They will issue you with a filming application form and liaise with on-site staff regarding the feasibility of what you want to do. The application form is not a permit to film, permission is granted if the property can accommodate you and a filming contract is issued by this office and signed by both parties. • This office does not deal with: student photo shoots and filming, wedding photos, news crews or radio. Please direct queries to 01304 207326 or [email protected] • All crews must hold £5m worth of public liability insurance (or the equivalent in their currency.) No crew of any size can film at a National Trust site without this. • We welcome reccie visits and are happy to meet you to discuss your filming needs – please call the filming and location team to arrange a visit. • Great shots of the cliff are easily accessible with a 2 minute walk from our car park. • There is limited access to the cliff-top for vehicles – however access for vehicles can be arranged to selected locations if arranged in advance with the filming office. • There is no access to the beach below the cliffs from our land. • The lighthouse is not usually open everyday of the week, so private access can be arranged if required. -

Seascape Character Assessment Report

Seascape Character Assessment for the South East Inshore marine plan area MMO 1134: Seascape Character Assessment for the South East Inshore marine plan area September 2018 Report prepared by: Land Use Consultants (LUC) Project funded by: European Maritime Fisheries Fund (ENG1595) and the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Version Author Note 0.1 Sally Marshall First draft desk-based report completed May 2015 Kate Ahern 1.0 Kate Ahern Updated draft final report following stakeholder consultation, August 2018 1.1 Chris Graham, MMO Comments David Hutchinson 2.0 Kate Ahern Final report, September 2018 2.1 Chris Sweeting Independent QA © Marine Management Organisation 2018 You may use and re-use the information featured on this website (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. Visit www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government- licence/ to view the licence or write to: Information Policy Team The National Archives Kew London TW9 4DU Email: [email protected] Information about this publication and further copies are available from: Marine Management Organisation Lancaster House Hampshire Court Newcastle upon Tyne NE4 7YH Tel: 0300 123 1032 Email: [email protected] Website: www.gov.uk/mmo Disclaimer This report contributes to the Marine Management Organisation (MMO) evidence base which is a resource developed through a large range of research activity and methods carried out by both MMO and external experts. The opinions expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of MMO nor are they intended to indicate how MMO will act on a given set of facts or signify any preference for one research activity or method over another. -

The White Cliffs of Dover 0919.Indd

Walk 7 The White Cliffs of Dover Distance - 7½ or 5½ miles A ‘there and back’ ramble that offers a high degree of WALK satisfaction with many interesting features along the From the Visitor Centre head towards the eastern end of the The gardens contain a statue of Sir Winston Churchill, way. Also, far reaching glimpses of the French coastline car parking area (walking away from Dover) and locate a donated by the St. Margaret’s Bay Trust and unveiled by can be observed (subject to conditions) from the Saxon Saxon Shore Way marker post. This invites a manoeuvre slightly his grandson Winston Churchill MP, on 20 November 1972. Shore Way footpath which follows a well used route left, away from the gravel path, passing beneath the modern above the evocatively named White Cliffs of Dover. At the junction soon after, swing right, descending towards coastguard station on the left with Langdon Bay to the right. St. Margaret’s Bay. The Saxon Shore Way was inaugurated in 1980. Watch out for the Exmoor ponies, which have been introduced Along the way notice a Victorian letter box and a section of Additionally, starting from the National Trust White to graze the chalkland grasses. Also, note the cabbage-like ancient wall on the right. The wall formed part of a defence Cliffs car park and Gateway Visitor Centre, high plants seen along the clifftop throughout. Sea Kale? above Dover harbour, the nautical manoeuvres of the system during the threat of invasion in Napoleonic times. Stride out along the cliff top route walking above Crab Bay See affixed plaque. -

South Foreland to Beachy Head Shoreline Management Plan April 2006

South Foreland to Beachy Head Shoreline Management Plan April 2006 South Foreland to Beachy Head SMP South Foreland to Beachy Head Shoreline Management Plan April 2006 1 INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 The Shoreline Management Plan .......................................................................................... 1 1.2 Structure of the SMP.............................................................................................................. 3 1.3 The Plan Development Process ............................................................................................ 4 2 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT................................................................................................. 7 2.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 7 2.2 The Appraisal Process ........................................................................................................... 7 2.3 Stakeholder Engagement....................................................................................................... 7 2.4 The Existing Environment ...................................................................................................... 8 2.5 Environmental Objectives ...................................................................................................... 8 2.6 Identification and Review of Possible Policy Scenarios........................................................ -

St Margaret's

DID YOU KNOW? Marconi conducted experiments in radio communication at South Foreland lighthouse. St Margaret’s Bay was a regular landing point for smugglers in East Kent. St Margaret’s smock windmill was constructed in 1928 to generate power. Dover Patrol Memorial, an impressive needle memorial on The Leas, commemorates the heroism of the Royal Navy’s Dover Patrol in two World Wars. Both playwright Noel Coward and author Ian Fleming – creator of James Bond – made their home at St Margaret’s Bay – it’s the white washed house on the beach! St. Margaret’s Museum. The centrepiece of the bottom of the valley, the route passes the Pines Gardens is a brooding statue of through the middle of the former gun Winston Churchill – a reminder in bronze position of a high velocity howitzer “Bruce”. of Britain’s darkest days when Nazi invaders Follow the path uphill again on to The Leas were just 20 miles (32km) away. The entrance where the former Coastguard Station has to the St Margaret’s Museum is dramatically been converted into the welcoming 1950’s guarded by two naval cannons. The path Mrs Knotts tearoom with excellent Channel then leads through Lighthouse Down and views. Continue along the clifftops where past the whitewashed South Foreland the underground military defences are now Lighthouse. The striking Victorian lighthouse securely barred to keep people out. This is a ST MARGARET’S BAY is now conserved by the National Trust. The good place to look for the tracks and burrows concrete remnants of cross-Channel gun of foxes, badgers and rabbits. -

Walks in East Kent Ages to Take on the Walk Can Be Road Map: Ordered by Emailing When You’Re out Walking Multimap Website [email protected]

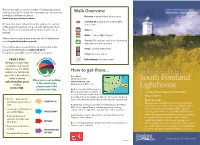

This circular walk is one of a number of walks produced by Photo Guide Kent County Council. If you liked this walk you can find more Walk Overview on the Explore Kent website at Distance: 4 miles (6.4km) allow 3 hours www.kent.gov.uk/explorekent Start/Finish: ‘Gateway to the White Cliffs’ We welcome any feedback about this walk or the content visitor centre of the guide. If you know of a good walk and would like to share it, please let us know and we may feature it on our Stiles: 1 website. Gates: 1 (also a flight of steps) 1 2 3 If the route description or pictures are out-of-date please e-mail [email protected] Terrain: Cliff top paths and tracks. Undulating with some short, steep slopes Please tell us about any problems concerning the paths using the Kent Report Line 0845 345 0210. Views: Some excellent views This guide is available in other formats on request. Toilets: At visitor centre FAMILY FUN! Refreshments: At visitor centre Walking is not only a healthy activity but it can be fun and 4 5 6 informative too. Free activity How to get there... worksheets for children of all Walks in East Kent ages to take on the walk can be Road Map: ordered by emailing When you’re out walking Multimap website [email protected] www.multimap.com. in the countryside, or calling Enter postcode CT16 1HJ please respect the 08458 247600. Countryside Code. By Car: From A2 – follow signs for Dover Castle from roundabout on 4 miles (6.4km) approx. -

Dover, St Margaret's and Martin Mill Railway

9 Following Lorraine's talk to the society at the October meeting it has been decided to publish the full story part 2 will appear in the next newsletter Editor Lorraine Sencicle t the cliff end of Athol Tterrace, near truction company that had been founded AEastern Docks, Dover, a steep by his late father, also called William. footpath leads up the cliff and then along Both father and son were the prime Langdon Cliffs towards St Margaret's. movers in the development of Dover's From the footpath, one can watch the town planning: daily activities of Dover's Eastern Docks - On the west side of the Dour cottages and Channel shipping beyond. On clear for the working class - Clarendon estate day, the coast of France with the Strait of - On the east side homes for the lower Dover, like a wide river, in between is middle class i.e. Barton Road quite a sight. As one traverses the path, neighbourhood - Below the Castle and it becomes apparent that it was once a nearer the sea, villas for the upper railway track. middle class i.e. the Castle Avenue estate. The next part of their dream for The story begins in 1892 when Dover Dover was to be a private estate on the Harbour Board (DHB) accepted the South Foreland for the well-to-do upper tender of John Jackson (1851-1919) for classes. the building of the Eastern Arm of the new Commercial Harbour - Crundall had been the Prince of Wales Pier. appointed to DHB in 1886 Four years later, in August and twenty years later, in 1896, the Undercliff 1906, he was elected Reclamation Act received Chairman of the Board.