The Two Stories of Rehoboam Ben Shlomo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solomon's Legacy

Solomon’s Legacy Divided Kingdom Image from: www.lightstock.com Solomon’s Last Days -1 Kings 11 Image from: www.lightstock.com from: Image ➢ God raises up adversaries to Solomon. 1 Kings 11:14 14 Then the LORD raised up an adversary to Solomon, Hadad the Edomite; he was of the royal line in Edom. 1 Kings 11:23-25 23 God also raised up another adversary to him, Rezon the son of Eliada, who had fled from his lord Hadadezer king of Zobah. 1 Kings 11:23-25 24 He gathered men to himself and became leader of a marauding band, after David slew them of Zobah; and they went to Damascus and stayed there, and reigned in Damascus. 1 Kings 11:23-25 25 So he was an adversary to Israel all the days of Solomon, along with the evil that Hadad did; and he abhorred Israel and reigned over Aram. Solomon’s Last Days -1 Kings 11 Image from: www.lightstock.com from: Image ➢ God tells Jeroboam that he will be over 10 tribes. 1 Kings 11:26-28 26 Then Jeroboam the son of Nebat, an Ephraimite of Zeredah, Solomon’s servant, whose mother’s name was Zeruah, a widow, also rebelled against the king. 1 Kings 11:26-28 27 Now this was the reason why he rebelled against the king: Solomon built the Millo, and closed up the breach of the city of his father David. 1 Kings 11:26-28 28 Now the man Jeroboam was a valiant warrior, and when Solomon saw that the young man was industrious, he appointed him over all the forced labor of the house of Joseph. -

2 CHRONICLES ‐ Chapter Outlines 1

2 CHRONICLES ‐ Chapter Outlines 1 9. Solomon and the Queen of Sheba 2 CHRONICLES [1] 10‐12. Rehoboam Over 2 Southern Tribes 2nd Chronicles is the Book of David’s Heritage. The narrative from 1st Chronicles continues 13. Jeroboam Over 10 Northern Tribes with the reign of Solomon, and the Kings of 14‐16. Good King Asa Judah down through Zedekiah and the 17‐20. Good King Jehoshaphat Babylonian Captivity. (note unholy alliance with Ahab) TITLE 21. Jehoram’s Reign [J] 1st & 2nd Chronicles (like Samuel & Kings) were 22. Only One Heir Left in the Royal Line of originally one Book. The Hebrew title Dibrey Christ, Joash Hayyamiym means “words (accounts) of the 23‐24. Reign of Joash [J] days.” The Greek (Septuagint) title, 25. Reign of Amaziah [J] Paraleipomenon, means “of things omitted.” This is rather misnamed, as Chronicles does 26. Reign of Uzziah [J] much more than provide omitted material as a 27. Reign of Jothan [J] supplement to Samuel & Kings. 28. Reign of Ahaz [J] The English title comes from Jerome’s Latin 29‐32. Reign of Hezekiah [J] Vulgate, which titled this Book Chronicorum 33. Reign of Manasseh (55) [J] Liber. 34‐35. Reign of Josiah [J] AUTHOR 36. The Babylonian Captivity The traditional author of Chronicles is Ezra the CHAPTER OUTLINES priest/scribe. The conclusion to 2nd Chronicles (36:22,23) is virtually identical with the 2 CHRONICLES 1 introduction to Ezra (1:1 3). Others choose to 1. Solomon began his reign with an act of leave the author anonymous, and call him the worship at the Tabernacle (2nd Chr. -

1 Kings 11:14-40 “Solomon's Adversaries”

1 Kings 11:14-40 “Solomon’s Adversaries” 1 Kings 11:9–10 9 So the LORD became angry with Solomon, because his heart had turned from the LORD God of Israel, who had appeared to him twice, 10 and had commanded him concerning this thing, that he should not go after other gods; but he did not keep what the LORD had commanded. Where were the Prophets David had? • To warn Solomon of his descent into paganism. • To warn Solomon of how he was breaking the heart of the Lord. o Do you have friends that care enough about you to tell you when you are backsliding against the Lord? o No one in the Electronic church to challenge you, to pray for you, to care for you. All of these pagan women he married (for political reasons?) were of no benefit. • Nations surrounding Israel still hated Solomon • Atheism, Agnostics, Gnostics, Paganism, and Legalisms are never satisfied until you are dead – and then it turns to kill your children and grandchildren. Exodus 20:4–6 4 “You shall not make for yourself a carved image—any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth; 5 you shall not bow down to them nor serve them. For I, the LORD your God, am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers upon the children to the third and fourth generations of those who hate Me, 6 but showing mercy to thousands, to those who love Me and keep My commandments. -

A Weekly Bible Reading Plan 1 Kings 12

67 Judah Israel A weekly Bible reading plan Rehoboam 930—913 Jeroboam I 930—909 Abijam 913—910 1 Kings 12-22 The Kingdom Divides Asa 910—869 Nadab 909—908 Overview Baasha* 908—886 Israel had grown to a nation of power, wealth, and prominence under the kingship of Solomon. Sadly, Suggested Reading Schedule Elah 886—885 Solomon’s poor choices of wives and idolatry would Zimri* 885 (7 Days) bring disaster to the kingdom. God promised the Monday: 1 Kings 12-14 kingdom would be split, and that’s exactly what Tuesday: 1 Kings 15-16 Omri* 885—874 happened shortly after Solomon’s son, Rehoboam, took the throne. Rehoboam apparently lacked his Wednesday: 1 Kings 17-18 Jehoshaphat 872—848 Ahab 874—853 father’s wisdom, and listened to the foolish counsel Thursday: 1 Kings 19-20 of peers instead of the wise advice of experienced Friday: 1 Kings 21-22 Ahaziah 853—852 men. The result was ten tribes of Israel rebelled and *Indicates a change of family line/kingdom takeover set up a man named Jeroboam as their king. This Bold names represent righteous kings became the northern nation of Israel, leaving only the tribes of Judah and Benjamin as the nation of Judah. The rest of First and Second Kings tells the story of these two kingdoms. A Dates are approximate dates of reign prominent portion of First Kings is also given to the prophet Elijah and his works. While none of the Old Testament books of prophecy were written by Elijah, he was considered one of the most powerful and important prophets, and we see why when we read his story! Questions: 1. -

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS in the SOLOMON NARRATIVE of 1 KINGS 1–11 John A

HEPTADIC VERBAL PATTERNS IN THE SOLOMON NARRATIVE OF 1 KINGS 1–11 John A. Davies Summary The narrative in 1 Kings 1–11 makes use of the literary device of sevenfold lists of items and sevenfold recurrences of Hebrew words and phrases. These heptadic patterns may contribute to the cohesion and sense of completeness of both the constituent pericopes and the narrative as a whole, enhancing the readerly experience. They may also serve to reinforce the creational symbolism of the Solomon narrative and in particular that of the description of the temple and its dedication. 1. Introduction One of the features of Hebrew narrative that deserves closer attention is the use (consciously or subconsciously) of numeric patterning at various levels. In narratives, there is, for example, frequently a threefold sequence, the so-called ‘Rule of Three’1 (Samuel’s three divine calls: 1 Samuel 3:8; three pourings of water into Elijah’s altar trench: 1 Kings 18:34; three successive companies of troops sent to Elijah: 2 Kings 1:13), or tens (ten divine speech acts in Genesis 1; ten generations from Adam to Noah, and from Noah to Abram; ten toledot [‘family accounts’] in Genesis). One of the numbers long recognised as holding a particular fascination for the biblical writers (and in this they were not alone in the ancient world) is the number seven. Seven 1 Vladimir Propp, Morphology of the Folktale (rev. edn; Austin: University of Texas Press, 1968; tr. from Russian, 1928): 74; Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots of Literature: Why We Tell Stories (London: Continuum, 2004): 229-35; Richard D. -

Text: 1 Kings 13:1-33 (NIV): John 14:15. Title: How to Overcome the Temptation of Disobeying God's Voice

Text: 1 Kings 13:1-33 (NIV): John 14:15. Title: How to Overcome the Temptation of Disobeying God’s Voice 1 By the word of the Lord a man of God came from Judah to Bethel, as Jeroboam was standing by the altar to make an offering. 2 By the word of the Lord he cried out against the altar: “Altar, altar! This is what the Lord says: ‘A son named Josiah will be born to the house of David. On you he will sacrifice the priests of the high places who make offerings here, and human bones will be burned on you.’” 3 That same day the man of God gave a sign: “This is the sign the Lord has declared: The altar will be split apart and the ashes on it will be poured out.” 4 When King Jeroboam heard what the man of God cried out against the altar at Bethel, he stretched out his hand from the altar and said, “Seize him!” But the hand he stretched out toward the man shriveled up, so that he could not pull it back. 5 Also, the altar was split apart and its ashes poured out according to the sign given by the man of God by the word of the Lord. 6 Then the king said to the man of God, “Intercede with the Lord your God and pray for me that my hand may be restored.” So the man of God interceded with the Lord, and the king’s hand was restored and became as it was before. -

1-And-2 Kings

FROM DAVID TO EXILE 1 & 2 Kings by Daniel J. Lewis © copyright 2009 by Diakonos, Inc. Troy, Michigan United States of America 2 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................... 4 Composition and Authorship ...................................................................................................................... 5 Structure ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Theological Motifs ..................................................................................................................................... 7 The Kingship of Solomon (1 Kings 1-11) .....................................................................................................13 Solomon Succeeds David as King (1:1—2:12) .........................................................................................13 The Purge (2:13-46) ..................................................................................................................................16 Solomon‟s Wisdom (3-4) ..........................................................................................................................17 Building the Temple and the Palace (5-7) .................................................................................................20 The Dedication of the Temple (8) .............................................................................................................26 -

Torah Texts Describing the Revelation at Mt. Sinai-Horeb Emphasize The

Paradox on the Holy Mountain By Steven Dunn, Ph.D. © 2018 Torah texts describing the revelation at Mt. Sinai-Horeb emphasize the presence of God in sounds (lwq) of thunder, accompanied by blasts of the Shofar, with fire and dark clouds (Exod 19:16-25; 20:18-21; Deut 4:11-12; 5:22-24). These dramatic, awe-inspiring theophanies re- veal divine power and holy danger associated with proximity to divine presence. In contrast, Elijah’s encounter with God on Mt. Horeb in 1 Kings 19:11-12, begins with a similar audible, vis- ual drama of strong, violent winds, an earthquake and fire—none of which manifest divine presence. Rather, it is hqd hmmd lwq, “a voice of thin silence” (v. 12) which manifests God, causing Elijah to hide his face in his cloak, lest he “see” divine presence (and presumably die).1 Revelation in external phenomena present a type of kataphatic experience, while revelation in silence presents a more apophatic, mystical experience.2 Traditional Jewish and Christian mystical traditions point to divine silence and darkness as the highest form of revelatory experience. This paper explores the contrasting theophanies experienced by Moses and the Israelites at Sinai and Elijah’s encounter in silence on Horeb, how they use symbolic imagery to convey transcendent spiritual realities, and speculate whether 1 Kings 19:11-12 represents a “higher” form of revela- tory encounter. Moses and Israel on Sinai: Three months after their escape from Egypt, Moses leads the Israelites into the wilderness of Sinai where they pitch camp at the base of Mt. -

2 Chronicles 1:1 2 CHRONICLES CHAPTER 1 King Solomon's Solemn Offering at Gibeon, 2Ch 1:1-6

2 Chronicles 1:1 2 CHRONICLES CHAPTER 1 King Solomon's solemn offering at Gibeon, 2Ch_1:1-6. His choice of wisdom is blessed by God, 2Ch_1:7-12. His strength and wealth, 1Ch_1:13-17. Was strengthened, or established , after his seditious brother Adonijah and his partisans were suppressed; and he was received with the universal consent and joy of his princes and people. 2 Chronicles 1:2 Then Solomon spake, to wit, concerning his intention of going to Gibeon, and that they should attend him thither, as the next verse shows. 2 Chronicles 1:3 To the high place; upon which the tabernacle was placed; whence it is called the great high place , 1Ki_3:4. 2 Chronicles 1:4 He separated the ark from the tabernacle, and brought it to Jerusalem, because there he intended to build a far more noble and lasting habitation for it. 2 Chronicles 1:5 He put; either Moses, mentioned 2Ch_1:3, or Bezaleel, here last named, by the command and direction of Moses; or David, who may be said to put it there, because he continued it there, and did not remove it, as he did the ark from the tabernacle. Sought unto it, i.e. sought the Lord and his favour by hearty prayers and sacrifices in the place which God had appointed for that work, Lev_17:3,4. 2 Chronicles 1:6 i.e. Which altar. But that he had now said, 2Ch_1:5, and therefore would not unnecessarily repeat it. Or rather, who ; and so these words are emphatical, and contain a reason why Solomon went thither, because the Lord was there graciously present to hear prayers and receive sacrifices. -

Bible Chronology of the Old Testament the Following Chronological List Is Adapted from the Chronological Bible

Old Testament Overview The Christian Bible is divided into two parts: the Old Testament and the New Testament. The word “testament” can also be translated as “covenant” or “relationship.” The Old Testament describes God’s covenant of law with the people of Israel. The New Testament describes God’s covenant of grace through Jesus Christ. When we accept Jesus as our Savior and Lord, we enter into a new relationship with God. Christians believe that ALL Scripture is “God-breathed.” God’s Word speaks to our lives, revealing God’s nature. The Lord desires to be in relationship with His people. By studying the Bible, we discover how to enter into right relationship with God. We also learn how Christians are called to live in God’s kingdom. The Old Testament is also called the Hebrew Bible. Jewish theologians use the Hebrew word “Tanakh.” The term describes the three divisions of the Old Testament: the Law (Torah), the Prophets (Nevi’im), and the Writings (Ketuvim). “Tanakh” is composed of the first letters of each section. The Law in Hebrew is “Torah” which literally means “teaching.” In the Greek language, it is known as the Pentateuch. It comprises the first five books of the Old Testament: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. This section contains the stories of Creation, the patriarchs and matriarchs, the exodus from Egypt, and the giving of God’s Law, including the Ten Commandments. The Prophets cover Israel’s history from the time the Jews entered the Promised Land of Israel until the Babylonian captivity of Judah. -

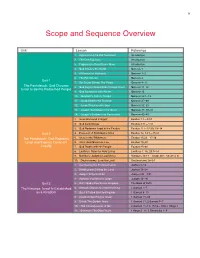

Scope and Sequence Overview

9 Scope and Sequence Overview Unit Lesson Reference 1. Approaching the Old Testament Introduction 2. The One Big Story Introduction 3. Preparing to Read God's Word Introduction 4. God Creates the World Genesis 1 5. A Mission for Humanity Genesis 1–2 6. The Fall into Sin Genesis 3 Unit 1 7. Sin Grows Worse: The Flood Genesis 4–11 The Pentateuch: God Chooses 8. God Begins Redemption through Israel Genesis 11–12 Israel to Be His Redeemed People 9. God Covenants with Abram Genesis 15 10. Abraham's Faith Is Tested Genesis 22:1–19 11. Jacob Inherits the Promise Genesis 27–28 12. Jacob Wrestles with God Genesis 32–33 13. Joseph: God Meant It for Good Genesis 37; 39–41 14. Joseph's Brothers Are Reconciled Genesis 42–45 1. Israel Enslaved in Egypt Exodus 1:1—2:10 2. God Calls Moses Exodus 2:11—4:31 3. God Redeems Israel in the Exodus Exodus 11:1–12:39; 13–14 Unit 2 4. Passover: A Redemption Meal Exodus 12; 14:1—15:21 The Pentateuch: God Redeems 5. Israel in the Wilderness Exodus 15:22—17:16 Israel and Expects Covenant 6. Sinai: God Gives His Law Exodus 19–20 Loyalty 7. God Dwells with His People Exodus 25–40 8. Leviticus: Rules for Holy Living Leviticus 1; 16; 23:9–14 9. Numbers: Judgment and Mercy Numbers 13:17—14:45; 20:1–13; 21:4–8 10. Deuteronomy: Love the Lord! Deuteronomy 28–34 1. Conquering the Promised Land Joshua 1–12 2. -

Elijah in the Bible Selections

Elijah the Prophet: The Man Who Never Died 1. Ahab son of Omri did evil in eyes of YHVH, more than all who preceded him. As though it were a light thing for him to follow in the sins of Jeroboam son of Nebat [who had set up golden calves], he took as his wife Jezebel, daughter of Ethbaal king of the Sidonians, and he went and served Baal and bowed down to him. And he set up an altar to Baal in the house of Baal that he built in Samaria. ha-asherah), an asherah [a cultic pole or stylized tree) האשרה And Ahab made symbolizing the goddess Asherah, a consort of Baal]. Ahab did more to vex YHVH, God of Israel, than all the kings of Israel who preceded him. (1 Kings 16:31–33) 2. Elijah the Tishbite, of the inhabitants of Gilead, said to Ahab, “By the life of YHVH God of Israel, whom I have served, there shall be no rain or dew these years except by my word.” (1 Kings 17:1) 3. Eliyyahu, “My God is Yahu.” 4. Go from here and turn eastward and hide in the wadi of Cherith, which is by the Jordan. And it shall be, that from the wadi you shall drink, and the ravens I have commanded to sustain you there” (1 Kings 17:3–4) The wadi dried up, for there was no rain in the land (17:7). 5. The widow says to Elijah: By the life of YHVH your God, I have no loaf but only a handful of flour in the jar and a bit of oil in the jug, and here I am gathering a couple of sticks, so I can go in and make it for me and my son, and we will eat it and die (17:12).