Islands of the Californias

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2012 Planting Lines

San Clemente Island Native Habitat Restoration Program Native Seed Collection, Propagation and Outplanting in Support of San Clemente Island Endangered Species Programs Under Contract With: Naval Facilities Engineering Command Southwest San Diego, California N68711 -05-D-3605-0077 Prepared By: Emily Howe, Korie Merrill, Thomas A. Zink. Soil Ecology and Restoration Group San Diego State University Research Foundation, San Diego, CA Prepared for: Natural Resources Office Environmental Department, Commander, Navy region Southwest, San Diego, CA Table Of Contents Table Of Contents ................................................................................................................ 2 Table of Figures ................................................................................................................... 2 Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 4 1.0 Native Plant Nursery ..................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Nursery Inventory .......................................................................................................... 4 1.2 Seed propagation ........................................................................................................... 5 2.0 Rainfall Data Collection ................................................................................................ 6 3.0 Seed Collection ............................................................................................................. -

Artemisia Californica Less

I. SPECIES Artemisia californica Less. [Updated 2017] NRCS CODE: Subtribe: Artemisiinae ARCA11 Tribe: Anthemideae (FEIS CODE: Family: Asteraceae ARCAL) Order: Asterales Subclass: Asteridae Class: Magnoliopsida flowering heads spring growth seedling, March 2009 juvenile plant photos A. Montalvo flowering plant, November 2005 mature plant with flower buds August 2010 A. Subspecific taxa None. Artemisia californica Less. var. insularis (Rydb.) Munz is now recognized as Artemisia nesiotica P.H. Raven (Jepson eFlora 2017). B. Synonyms Artemisia abrotanoides Nuttall; A. fischeriana Besser; A. foliosa Nuttall; Crossostephium californicum (Lessing) Rydberg (FNA 2017). C. Common name California sagebrush. The common name refers to its strong, sage-like aroma and endemism to California and Baja California. Other names include: coastal sage, coast sage, coast sagebrush (Painter 2016). D. Taxonomic relationships The FNA (2017) places this species in subgenus Artemisia . The molecular phylogeny of the genus has improved the understanding of relationships among the many species of Artemisia and has, at times, placed the species in subgenus Tridentadae; morphology of the inflorescences and flowers alone does not place this species with its closest relatives (Watson et al. 2002). The detailed phylogeny is not completely resolved (Hayat et al. 2009). E. Related taxa in region There are 18 species and a total of 31 taxa (including infrataxa) of Artemisia in southern California, all of which differ clearly from A. californica in habitat affinity, structure, or both (Munz 1974, Jepson eFlora 2017). Within subgenus Artemisia (as per FNA 2017), A. nesiotica from the Channel Islands is the most similar and was once considered part of A. californica ; it can be distinguished by its wider leaves with flat leaf margins (not rolled under). -

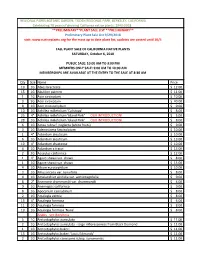

Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies Bracteata 12.00 $ 15 1G Abutilon

REGIONAL PARKS BOTANIC GARDEN, TILDEN REGIONAL PARK, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA Celebrating 78 years of growing California native plants: 1940-2018 **PRELIMINARY**PLANT SALE LIST **PRELIMINARY** Preliminary Plant Sale List 9/29/2018 visit: www.nativeplants.org for the most up to date plant list, updates are posted until 10/5 FALL PLANT SALE OF CALIFORNIA NATIVE PLANTS SATURDAY, October 6, 2018 PUBLIC SALE: 10:00 AM TO 3:00 PM MEMBERS ONLY SALE: 9:00 AM TO 10:00 AM MEMBERSHIPS ARE AVAILABLE AT THE ENTRY TO THE SALE AT 8:30 AM Qty Size Name Price 10 1G Abies bracteata $ 12.00 15 1G Abutilon palmeri $ 11.00 1 1G Acer circinatum $ 10.00 3 5G Acer circinatum $ 40.00 8 1G Acer macrophyllum $ 9.00 10 1G Achillea millefolium 'Calistoga' $ 8.00 25 4" Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 5.00 28 1G Achillea millefolium 'Island Pink' OUR INTRODUCTION! $ 8.00 6 1G Actea rubra f. neglecta (white fruits) $ 9.00 3 1G Adenostoma fasciculatum $ 10.00 1 4" Adiantum aleuticum $ 10.00 6 1G Adiantum aleuticum $ 13.00 10 4" Adiantum shastense $ 10.00 4 1G Adiantum x tracyi $ 13.00 2 2G Aesculus californica $ 12.00 1 4" Agave shawii var. shawii $ 8.00 1 1G Agave shawii var. shawii $ 15.00 4 1G Allium eurotophilum $ 10.00 3 1G Alnus incana var. tenuifolia $ 8.00 4 1G Amelanchier alnifolia var. semiintegrifolia $ 9.00 8 2" Anemone drummondii var. drummondii $ 4.00 9 1G Anemopsis californica $ 9.00 8 1G Apocynum cannabinum $ 8.00 2 1G Aquilegia eximia $ 8.00 15 4" Aquilegia formosa $ 6.00 11 1G Aquilegia formosa $ 8.00 10 1G Aquilegia formosa 'Nana' $ 8.00 Arabis - see Boechera 5 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos auriculata - large inflorescences from Black Diamond $ 11.00 1 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri $ 11.00 15 1G Arctostaphylos bakeri 'Louis Edmunds' $ 11.00 2 1G Arctostaphylos canescens subsp. -

Private Boating and Boater Activities in the Channel Islands: a Spatial Analysis and Assessment

CALIFORNIA MARINE RECREATION Catamaran at anchor, Coches Prietos anchorage Private Boating and Boater Activities in the Channel Islands: A spatial analysis and assessment FINAL REPORT Prepared for: The Resources Legacy Fund Foundation (RLFF) The National Marine Sanctuary Program (NMSP) Prepared by: Chris LaFranchi1 Linwood Pendleton2 March 2008 1 Founder, NaturalEquity (www.naturalequity.org) Social Science Coordinator, Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary (CINMS) Email: [email protected] 2 Senior Fellow and Director of Economic Research The Ocean Foundation, Dir. Coastal Ocean Values Center Adjunct Associate Professor, UCLA www.coastalvalues.org Email: [email protected] Acknowledgments Of the many individuals who contributed to this effort, we thank Bob Leeworthy, Ryan Vaughn, Miwa Tamanaha, Allison Chan, Erin Gaines, Erin Myers, Dennis Carlson, Alexandra Brown, the captain and crew of the research vessel Shearwater, volunteers from the Sanctuary’s Naturalist Corps, Susie Williams, Christy Loper, Peter Black, and the man boaters who volunteered their time during focus group meetings and survey pre-test efforts. 2 Contents Page 1. Summary……………………………. ……………………………….. 4 2. Introduction …………………………………………………………... 18 2.1. The Study ………………………….…………………………….. 18 2.2. Background ………………………….…………………………… 19 2.3. The Human Dimension of Marine Management ………………… 19 2.4. The Need for Baseline Data ……………………………………... 20 2.5. Policy and Management Context ………………………………... 21 2.6. Market and Non-Market Economics of Non-Consumptive Use … 22 3. Research Tasks and Methods ………………………………………… 25 3.1. Overall Approach ………………………………………………… 25 3.2. Use of Four Integrated Survey Instruments …………….……….. 26 3.3. Biophysical Attributes of the Marine Environment ……………… 30 4. Baseline Data Set ……………………………………………………. 32 4.1. Summary of Responses: Postcard Survey Of Private Boaters….. 32 4.2. -

Ramirez Dissertation

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Comparative Ecophysiology and Evolutionary Biology of Island and Mainland Chaparral Communities Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5b7510px Author Ramirez, Aaron Robert Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Comparative Ecophysiology and Evolutionary Biology of Island and Mainland Chaparral Communities By Aaron Robert Ramirez A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor David D. Ackerly, Chair Professor Paul V. A. Fine Professor Scott L. Stephens Spring 2015 Comparative Ecophysiology and Evolutionary Biology of Island and Mainland Chaparral Communities © 2015 by Aaron Robert Ramirez Abstract Comparative Ecophysiology and Evolutionary Biology of Island and Mainland Chaparral Communities by Aaron Robert Ramirez Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor David D. Ackerly, Chair The unique nature of island ecosystems have fascinated generations of naturalists, ecologists, and evolutionary biologists. Studying island systems led to the development of keystone biological theories including: Darwin and Wallace’s theories of natural selection, Carlquist’s insights into the biology of adaptive radiations, MacArthur and Wilson’s theory of island biogeography, and many others. Utilizing islands as natural laboratories allows us to discover the underlying fabric of ecology and evolutionary biology. This dissertation represents my attempt to contribute to this long and storied scientific history by thoroughly investigating two aspects of island biology: 1. the role of island climate in shaping drought tolerance of woody plants, and 2. -

Evaluating the Future Role of the University of California Natural Reserve System for Sensitive Plant Protection Under Climate Change

Evaluating the Future Role of the University of California Natural Reserve System for Sensitive Plant Protection under Climate Change ERIN C. RIORDAN* AND PHILIP W. RUNDEL DEPARTMENT OF ECOLOGY AND EVOLUTIONARY BIOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90095 USA *EMAIL FOR CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] WINTER 2019 PREPARED FOR THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA NATURAL RESERVE SYSTEM Executive Summary Description Protected areas are critical for conserving California’s many sensitive plant species but their future role is uncertain under climate change. Climate-driven species losses and redistributions could dramatically affect the relevance of protected areas for biodiversity conservation this century. Focusing on the University of California Natural Reserve System (NRS), we predicted the future impact of climate change on reserve effectiveness with respect to sensitive plant protection. First, we evaluated the historical representation of sensitive plant species in the NRS reserve network by compiling species accounts from checklists, floras, and spatial queries of occurrence databases. Next, we calculated projected climate change exposure across the NRS reserve network for the end of the 21st century (2070–2099) relative to baseline (1971–2000) conditions under five future climate scenarios. We then predicted statewide changes in suitable habitat for 180 sensitive plant taxa using the same future climate scenarios in a species distribution modeling approach. Finally, from these predictions we evaluated suitable habitat retention at three spatial scales: individual NRS reserves (focal reserves), the NRS reserve network, and the surrounding mosaic of protected open space. Six reserves—Sagehen Creek Field Station, McLaughlin Natural Reserve, Jepson Prairie Reserve, Landels-Hill Big Creek Reserve, Sedgwick Reserve, and Boyd Deep Canyon Desert Research Center—were selected as focal reserves for analyses. -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions............................................................................................. -

San Miguel Island Trail Guide Timhaufphotography.Com Exploring San Miguel Island

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Channel Islands National Park San Miguel Island Trail Guide timhaufphotography.com Exploring San Miguel Island Welcome to San Miguel Island, one of private boaters to contact the park to five islands in Channel Islands National ensure the island is open before coming Park. This is your island. It is also your ashore. responsibility. Please take a moment to read this bulletin and learn what you Many parts of San Miguel are closed can do to take care of San Miguel. This to protect wildlife, fragile plants, and information and the map on pages three geological features. Several areas, and four will show you what you can see however, are open for you to explore on and do here on San Miguel. your own. Others are open to you only when accompanied by a park ranger. About the Island San Miguel is the home of pristine On your own you may explore the tidepools, rare plants, and the strange Cuyler Harbor beach, Nidever Canyon, caliche forest. Four species of seals and Cabrillo monument, and the Lester ranch sea lions come here to breed and give site. Visitors are required to stay on the birth. For 10,000 years the island was designated island trail system. No off- home to the seagoing Chumash people. trail hiking is permitted. The island was Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo set foot here a bombing range and there are possible in 1542 as the first European to explore unexploded ordnance. In addition, the California coast. For 100 years the visitors must be accompanied by a ranger island was a sheep ranch and after that beyond the ranger station. -

A New Combination in Acmispon (Fabaceae: Loteae) for California Luc Brouillet Université De Montréal, Montreal, Canada

Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany Volume 28 | Issue 1 Article 6 2010 A New Combination in Acmispon (Fabaceae: Loteae) for California Luc Brouillet Université de Montréal, Montreal, Canada Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso Part of the Botany Commons, and the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons Recommended Citation Brouillet, Luc (2010) "A New Combination in Acmispon (Fabaceae: Loteae) for California," Aliso: A Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Botany: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 6. Available at: http://scholarship.claremont.edu/aliso/vol28/iss1/6 Aliso, 28, p. 63 ’ 2010, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden A NEW COMBINATION IN ACMISPON (FABACEAE: LOTEAE) FOR CALIFORNIA LUC BROUILLET Herbier Marie-Victorin, Institut de recherche en biologie ve´ge´tale, Universite´de Montre´al, 4101 Sherbrooke St. E, Montreal, Quebec, Canada H1X 2B2 ([email protected]) ABSTRACT The new combination Acmispon argophyllus (A.Gray) Brouillet var. niveus (Greene) Brouillet is made. Key words: Acmispon, California, Fabaceae, Loteae, North America, Santa Cruz Island. Acmispon argophyllus (A.Gray) Brouillet var. niveus (Greene) Variety niveus is a northern Channel Islands (California) Brouillet, comb. et stat. nov.—TYPE: California. Santa endemic that is distinguished from the closely related southern Cruz Island [s.d.], E.L. Greene s.n. (holotype CAS!, isotype Channel Islands endemic var. adsurgens (Dunkle) Brouillet by (part of type) UC!). stems ascending to erect (vs. erect), less crowded leaves, a silky (vs. silvery) indumentum, smaller umbels (6–10 vs. 10–13 Basionym: Syrmatium niveum Greene, Bull. Calif. Acad. Sci. 2: 148 flowers), and slightly longer calyx lobes (2.5–5.0 vs. -

Birds on San Clemente Island, As Part of Our Work Toward the Recovery of the Island’S Endangered Species

WESTERN BIRDS Volume 36, Number 3, 2005 THE BIRDS OF SAN CLEMENTE ISLAND BRIAN L. SULLIVAN, PRBO Conservation Science, 4990 Shoreline Hwy., Stinson Beach, California 94970-9701 (current address: Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, 159 Sapsucker Woods Rd., Ithaca, New York 14850) ERIC L. KERSHNER, Institute for Wildlife Studies, 2515 Camino del Rio South, Suite 334, San Diego, California 92108 With contributing authors JONATHAN J. DUNN, ROBB S. A. KALER, SUELLEN LYNN, NICOLE M. MUNKWITZ, and JONATHAN H. PLISSNER ABSTRACT: From 1992 to 2004, we observed birds on San Clemente Island, as part of our work toward the recovery of the island’s endangered species. We increased the island’s bird list to 317 species, by recording many additional vagrants and seabirds. The list includes 20 regular extant breeding species, 6 species extirpated as breeders, 5 nonnative introduced species, and 9 sporadic or newly colonizing breeding species. For decades San Clemente Island had been ravaged by overgrazing, especially by goats, which were removed completely in 1993. Since then, the island’s vegetation has begun recovering, and the island’s avifauna will likely change again as a result. We document here the status of that avifauna during this transitional period of re- growth, between the island’s being largely denuded of vegetation and a more natural state. It is still too early to evaluate the effects of the vegetation’s still partial recovery on birds, but the beginnings of recovery may have enabled the recent colonization of small numbers of Grasshopper Sparrows and Lazuli Buntings. Sponsored by the U. S. Navy, efforts to restore the island’s endangered species continue—among birds these are the Loggerhead Shrike and Sage Sparrow. -

November 2009 an Analysis of Possible Risk To

Project Title An Analysis of Possible Risk to Threatened and Endangered Plant Species Associated with Glyphosate Use in Alfalfa: A County-Level Analysis Authors Thomas Priester, Ph.D. Rick Kemman, M.S. Ashlea Rives Frank, M.Ent. Larry Turner, Ph.D. Bernalyn McGaughey David Howes, Ph.D. Jeffrey Giddings, Ph.D. Stephanie Dressel Data Requirements Pesticide Assessment Guidelines Subdivision E—Hazard Evaluation: Wildlife and Aquatic Organisms Guideline Number 70-1-SS: Special Studies—Effects on Endangered Species Date Completed August 22, 2007 Prepared by Compliance Services International 7501 Bridgeport Way West Lakewood, WA 98499-2423 (253) 473-9007 Sponsor Monsanto Company 800 N. Lindbergh Blvd. Saint Louis, MO 63167 Project Identification Compliance Services International Study 06711 Monsanto Study ID CS-2005-125 RD 1695 Volume 3 of 18 Page 1 of 258 Threatened & Endangered Plant Species Analysis CSI 06711 Glyphosate/Alfalfa Monsanto Study ID CS-2005-125 Page 2 of 258 STATEMENT OF NO DATA CONFIDENTIALITY CLAIMS The text below applies only to use of the data by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) in connection with the provisions of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA) No claim of confidentiality is made for any information contained in this study on the basis of its falling within the scope of FIFRA §10(d)(1)(A), (B), or (C). We submit this material to the United States Environmental Protection Agency specifically under the requirements set forth in FIFRA as amended, and consent to the use and disclosure of this material by EPA strictly in accordance with FIFRA. By submitting this material to EPA in accordance with the method and format requirements contained in PR Notice 86-5, we reserve and do not waive any rights involving this material that are or can be claimed by the company notwithstanding this submission to EPA. -

The Genus Ceanothus: Wild Lilacs and Their Kin

THE GENUS CEANOTHUS: WILD LILACS AND THEIR KIN CEANOTHUS, A GENUS CENTERED IN CALIFORNIA AND A MEMBER OF THE BUCKTHORN FAMILY RHAMNACEAE The genus Ceanothus is exclusive to North America but the lyon’s share of species are found in western North America, particularly California • The genus stands apart from other members of the Rhamnaceae by • Colorful, fragrant flowers (blues, purples, pinks, and white) • Dry, three-chambered capsules • Sepals and petals both colored and shaped in a unique way, and • Three-sided receptacles that persist after the seed pods have dropped Ceanothus blossoms feature 5 hooded sepals, 5 spathula-shaped petals, 5 stamens, and a single pistil with a superior ovary Ceanothus seed pods are three sided and appear fleshy initially before drying out, turning brown, and splitting open Here are the three-sided receptacles left behind when the seed pods fall off The ceanothuses range from low, woody ground covers to treelike forms 20 feet tall • Most species are evergreen, but several deciduous kinds also occur • Several species feature thorny side branches • A few species have highly fragrant, resinous leaves • Habitats range from coastal bluffs through open woodlands & forests to chaparral and desert mountains The genus is subdivided into two separate subgenera that seldom exchange genes, even though species within each subgenus often hybridize • The true ceanothus subgenus (simply called Ceanothus) is characterized by • Alternate leaves with deciduous stipules • Leaves that often have 3 major veins (some have a single prominent midrib) • Flowers mostly in elongated clusters • Smooth seed pods without horns • The majority of garden species available belong to this group The leaves of C.