Wetlands, Water and the Law Using Law to Advance Wetland Conservation and Wise Use

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Framework for Assessing the Vulnerability of Wetlands to Climate Change

Ramsar Technical Reports Ramsar Technical Report No. 5 CBD Technical Series No. 57 A Framework for assessing the vulnerability of wetlands to climate change Habiba Gitay, C. Max Finlayson, and Nick Davidson 05 Ramsar Technical Report No. 5 CBD Technical Series No. 57 A Framework for assessing the vulnerability of wetlands to climate change Habiba Gitay1, C. Max Finlayson2 & Nick Davidson3 1 Senior Environmental Specialist, The World Bank, Washington DC, USA 2 Professor for Ecology and Biodiversity, Institute for Land, Water and Society, Charles Sturt University, Albury, Australia 3 Deputy Secretary General, Ramsar Convention Secretariat, Gland, Switzerland Ramsar Convention Secretariat Gland, Switzerland June 2011 Ramsar Technical Reports Published jointly by the Secretariat of the Convention on Wetlands (Ramsar, Iran, 1971) and the Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity. © Ramsar Convention Secretariat 2011; © Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity 2011. This report should be cited as: Gitay, H., Finlayson, C.M. & Davidson, N.C. 2011. A Framework for assessing the vulnerability of wetlands to climate change. Ramsar Technical Report No. 5/CBD Technical Series No. 57. Ramsar Convention Secretariat, Gland, Switzerland & Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, Montreal, Canada. ISBN 92-9225-361-1 (print); 92-9225-362-X (web). Series editors: Heather MacKay (Chair of Ramsar Scientific & Technical Review Panel), Max Finlayson (former Chair of Ramsar Scientific & Technical Review Panel), and Nick Davidson (Deputy Secretary General, Ramsar Convention Secretariat). Design & layout: Dwight Peck (Ramsar Convention Secretariat). Cover photo: Laguna Brava Ramsar Site, Argentina (Horacio de la Fuente) Ramsar Technical Reports are designed to publish, chiefly through electronic media, technical notes, reviews and reports on wetland ecology, conservation, wise use and management, as an information support service to Contracting Parties and the wider wetland community in support of implementation of the Ramsar Convention. -

The Pond Manifesto

The Pond Manifesto Contents 1 About this document . 5 2 Why protect ponds? . .6 2.1 Overview . .6 2.2 The pond resource . .6 2.3 Pond biodiversity value . .8 2.4 Pond cultural and social value . .10 2.5 Pond economic value and ecosystem services . .12 3 Threats to Ponds . .14 4 Strategy for the conservation of ponds in Europe . .16 4.1 Policy and legislation . .17 4.2 Research and monitoring . .17 4.3 Communication and awareness raising . .18 4.4 Conservation of the pond resource . .19 5 Conclusion: pond conservation is an opportunity . .19 This document sets out the case for the conservation of ponds in a straightforward and convincing manner Acknowledgements Thank you to the very many people who have contributed to the Pond Manifesto, and to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands and the MAVA Foundation for their support. Thank you also to all the photographers for the use of their images (a list of photographers is available on the EPCN website: www.europeanponds.org) © European Pond Conservation Network 2008 2 Foreword The importance of maintaining global freshwater biodiversity and ensuring its sustainable use cannot be over-emphasised. Wetland ecosystems, including the associated waterbodies, come in all shapes and sizes and all have a role to play. The larger ones, perhaps inevitably, have enjoyed the most attention – it is easy to overlook the many small waterbodies scattered across the landscape. Fortunately, over the last decade, our knowledge and attitude towards small wetlands like ponds has begun to change. We know now that they are crucial for biodiversity This and can also provide a whole range of ecosystem services. -

Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Strategic Environmental Assessment Influential Case Studies

Cover page: Ecosystem services around the world Top right: Pantanal, Brasil: the world’s largest freshwater wetland, is a paradise for bird photographers. Nature tourism is booming in the area. Left: Kerala, India: the Kuttanad backwaters are protected from storm surges by a coastal belt of coconut trees. The coconuts provide fiber for a large coir industry. The backwaters provide the only means of transport in the area. Centre: Benue valley, Cameroon: in rural Africa wood still is the main source of energy. When resources suffer from overexploitation, women (and children) have to walk ever- increasing distances to collect firewood. Bottom right: Madeira, Portugal: often referred to as the island of flowers, here sold on the local market. (Photographs © SevS/Slootweg) Valuation of Ecosystem Services and Strategic Environmental Assessment Influential Case Studies Pieter J.H. van Beukering Roel Slootweg Desirée Immerzeel 11 September, 2008 Commission for Environmental Assessment P.O. box 2345 NL-3500 GH Utrecht, The Netherlands www.eia.nl Economic valuation and Strategic Environmental Assessment 3 Contents Contents 3 1. Introduction 5 2. West Delta Water Conservation and Irrigation Rehabilitation Project, Egypt 8 2.1 Introduction to the case 8 2.2 Context of the case study: the planning process 9 2.3 Assessment context 9 2.4 Ecosystem services & valuation 10 2.5 Decision making 13 2.6 SEA boundary conditions 13 2.7 References / Sources of information 16 3. Aral Sea Wetland Restoration Strategy 18 3.1 Introduction to the case 18 3.2 Context of the case study: the planning process 19 3.3 Assessment context 19 3.4 Ecosystem services & valuation 20 3.5 Decision making 25 3.6 SEA boundary conditions 26 3.7 References / Sources of information 27 4. -

Texas: Upper Coast Cumulative Bird List Column A: Number of Tours (Out of 16) on Which Species Seen Column B: Number of Days Th

Texas: Upper Coast Cumulative Bird List Column A: Number of tours (out of 16) on which species seen Column B: number of days this species was seen on the 2019 tour Column C: maximum daily count for this species on the 2019 tour Column D: E = endemic; H = Heard only A B C D 16 Black-bellied Whistling -Duck 5 30 Dendrocygna autumnalis 15 Fulvous Whistling-Duck 4 200 Dendrocygna bicolor 1 Greater White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons 5 Snow Goose Chen caerulescens 11 Wood Duck 1 2 Aix sponsa 12 Gadwall 2 40 Anas strepera 10 American Wigeon Anas americana 7 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos 16 Mottled Duck 4 20 Anas fulvigula maculosa 16 Blue-winged Teal 5 150 Anas discors 2 Cinnamon Teal Anas cyanoptera 15 Northern Shoveler 2 3 Anas clypeata 2 Northern Pintail Anas acuta 7 Green-winged Teal 1 3 Anas crecca 12 Lesser Scaup 2 12 Aythya affinis 1 Ring-necked Duck 1 1 Aythya collaris 1 King Eider Somateria spectabilis 3 Surf Scoter Melanitta perspicillata 2 Black Scoter 1 2 Melanitta nigra 1 Long-tailed Duck Clangula hyemalis 13 Red-breasted Merganser Mergus serrator 2 Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis 7 Northern Bobwhite Colinus virginianus 1 Wild Turkey Meleagris gallopavo 15 Pied-billed Grebe 3 20 Podilymbus podiceps 2 Eared Grebe Podiceps nigricollis 16 Rock Pigeon 5 25 Columba livia 16 Eurasian Collared-Dove 3 10 Streptopelia decaocto 16 White-winged Dove 5 10 Zenaida asiatica 16 Mourning Dove 6 6 Zenaida macroura ________________________________________________________________________________________________________ WINGS ● 1643 N. Alvernon Way Ste. -

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015

Draft Informational Report Chabot Gun Club and Facility Operations at Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range Revised October 28, 2015 I. Introduction The Board of Directors (“Board”) has requested information relating to facility operations at the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range (“Chabot Gun Range” or “gun range”), including estimated capital and operation and maintenance costs required for continued operation of the gun range. As discussed below, District staff has gathered information regarding environmental compliance, facility conditions and deferred maintenance, sound impacts and mitigation options, and information related to use, revenue, and operational costs of the gun range. II. CEQA Compliance No action by the Board is being requested at this time, and therefore no action is necessary to comply with CEQA for purposes of this Board item. However, a decision by the Board to consider entry into a long term extension of the Chabot Gun Club’s lease would first require environmental review under CEQA, most likely the preparation of an environmental impact report (EIR). III. History of the Chabot Gun Range In 1963, the Anthony Chabot Marksmanship Range was developed in cooperation with the Oakland Pistol Club, which had previously leased a site in Knowland Park, Oakland, California. The original 1962 lease was a partnership between the District and the Oakland Pistol Club to construct, develop, operate and maintain a marksmanship range in Anthony Chabot Regional Park. In 1964, the original lease was amended to finalize the schedule and define the cost-share for construction of the Chabot Gun Range. In 1967, the District entered into a new long-term lease with Chabot Gun Club, Inc. -

Maritime Swamp Forest (Typic Subtype)

MARITIME SWAMP FOREST (TYPIC SUBTYPE) Concept: Maritime Swamp Forests are wetland forests of barrier islands and comparable coastal spits and back-barrier islands, dominated by tall trees of various species. The Typic Subtype includes most examples, which are not dominated by Acer, Nyssa, or Fraxinus, not by Taxodium distichum. Canopy dominants are quite variable among the few examples. Distinguishing Features: Maritime Shrub Swamps are distinguished from other barrier island wetlands by dominance by tree species of (at least potentially) large stature. The Typic Subtype is dominated by combinations of Nyssa, Fraxinus, Liquidambar, Acer, or Quercus nigra, rather than by Taxodium or Salix. Maritime Shrub Swamps are dominated by tall shrubs or small trees, particularly Salix, Persea, or wetland Cornus. Some portions of Maritime Evergreen Forest are marginally wet, but such areas are distinguished by the characteristic canopy dominants of that type, such as Quercus virginiana, Quercus hemisphaerica, or Pinus taeda. The lower strata also are distinctive, with wetland species occurring in Maritime Swamp Forest; however, some species, such as Morella cerifera, may occur in both. Synonyms: Acer rubrum - Nyssa biflora - (Liquidambar styraciflua, Fraxinus sp.) Maritime Swamp Forest (CEGL004082). Ecological Systems: Central Atlantic Coastal Plain Maritime Forest (CES203.261). Sites: Maritime Swamp Forests occur on barrier islands and comparable spits, in well-protected dune swales, edges of dune ridges, and on flats adjacent to freshwater sounds. Soils: Soils are wet sands or mucky sands, most often mapped as Duckston (Typic Psammaquent) or Conaby (Histic Humaquept). Hydrology: Most Maritime Swamp Forests have shallow seasonal standing water and nearly permanently saturated soils. Some may rarely be flooded by salt water during severe storms, but areas that are severely or repeatedly flooded do not recover to swamp forest. -

Scaling up for Impact: Europe Regional Strategy 2015 - 2025

Scaling up for impact: Europe regional strategy 2015 - 2025 Scaling up for impact: Europe Regional strategy 2015 – 2025 Wetlands International September 2016 Cover photo: Sava river. Photo by Romy Durst. 2 Wetlands International European Regional Strategy 2015 - 2025 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Our vision and mission ............................................................................................................................ 4 Our approach .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Why our work is needed ......................................................................................................................... 5 Our strategy ............................................................................................................................................ 6 How we work in Europe .................................................................................................................. 7 Geographical focus.......................................................................................................................... 8 Our niche and added value ............................................................................................................. 9 Our target groups ......................................................................................................................... -

PESHTIGO RIVER DELTA Property Owner

NORTHEAST - 10 PESHTIGO RIVER DELTA WETLAND TYPES Drew Feldkirchner Floodplain forest, lowland hardwood, swamp, sedge meadow, marsh, shrub carr ECOLOGY & SIGNIFICANCE supports cordgrass, marsh fern, sensitive fern, northern tickseed sunflower, spotted joe-pye weed, orange This Wetland Gem site comprises a very large coastal • jewelweed, turtlehead, marsh cinquefoil, blue skullcap wetland complex along the northwest shore of Green Bay and marsh bellflower. Shrub carr habitat is dominated three miles southeast of the city of Peshtigo. The wetland by slender willow; other shrub species include alder, complex extends upstream along the Peshtigo River for MARINETTE COUNTY red osier dogwood and white meadowsweet. Floodplain two miles from its mouth. This site is significant because forest habitats are dominated by silver maple and green of its size, the diversity of wetland community types ash. Wetlands of the Peshtigo River Delta support several present, and the overall good condition of the vegetation. - rare plant species including few-flowered spikerush, The complexity of the site – including abandoned oxbow variegated horsetail and northern wild raisin. lakes and a series of sloughs and lagoons within the river delta – offers excellent habitat for waterfowl. A number This Wetland Gem provides extensive, diverse and high of rare animals and plants have been documented using quality wetland habitat for many species of waterfowl, these wetlands. The area supports a variety of recreational herons, gulls, terns and shorebirds and is an important uses, such as hunting, fishing, trapping and boating. The staging, nesting and stopover site for many migratory Peshtigo River Delta has been described as the most birds. Rare and interesting bird species documented at diverse and least disturbed wetland complex on the west the site include red-shouldered hawk, black tern, yellow shore of Green Bay. -

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention

Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: the role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity edited by A. J. Hails Ramsar Convention Bureau Ministry of Environment and Forest, India 1996 [1997] Published by the Ramsar Convention Bureau, Gland, Switzerland, with the support of: • the General Directorate of Natural Resources and Environment, Ministry of the Walloon Region, Belgium • the Royal Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Denmark • the National Forest and Nature Agency, Ministry of the Environment and Energy, Denmark • the Ministry of Environment and Forests, India • the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Sweden Copyright © Ramsar Convention Bureau, 1997. Reproduction of this publication for educational and other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior perinission from the copyright holder, providing that full acknowledgement is given. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. The views of the authors expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of the Ramsar Convention Bureau or of the Ministry of the Environment of India. Note: the designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Ranasar Convention Bureau concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Citation: Halls, A.J. (ed.), 1997. Wetlands, Biodiversity and the Ramsar Convention: The Role of the Convention on Wetlands in the Conservation and Wise Use of Biodiversity. -

N at U R O P

N AT UROPA " BULLETIN OF THE EUROPEAN INFORMATION CENTRE FOR NATURE CONSERVATION COUNCIL OF EUROPE NATUROPA Number 22 eu ro p ean “Naturopa” is the new title of the bulletin formerly entitled "Naturope" (French version) and "Nature in Focus" (English version). information EDITORIAL G. G. Aym onin 1 cen tre THE MEDITERRANEAN FLORA for MUST BE SAVED J. M elato-Beliz 3 nature PLANT SPECIES CONSERVATION IN THE ALPS - conservation POSSIBILITIES AND PROBLEMS h . Riedl 6 THREATENED AND PROTECTED PLANTS IN THE NETHERLANDS J. Mennem a 10 G. G. AYMONIN THE HEILIGENHAFEN CONFERENCE ON THE Deputy Director of the Laboratory INTERNATIONAL CONSERVATION of Phanerogamy National Museum of Natural History OF WETLANDS AND WILDFOWL G. V. T. M atthews 16 Paris ENVIRONMENTAL CONSERVATION PROBLEMS IN MALTA L. J. Saliba 20 An international meeting of experts attempting to penetrate by analysing Norway across Siberia. Still in its specialising in problems associated what they term the “ecosystems”. natural state, often very dense and ECOLOGY IN A NEW BRITISH CITY J. G. Kelcey 23 with the impoverishment in plant spe Europe’s natural environments are practically impenetrable in places, it 26 cies of numerous natural environments characterized by a great diversity in is a magnificent forest of immense News from Strasbourg in Europe took place at Arc-et-Senans, their biological and aesthetic features. biological and economic value. Notes 28 France, in November 1973, under the From one end of the continent to the To the west of Norway and south of patronage of the Secretary General other the contrasts are striking. Most Sweden begin the forests of Central of the Council of Europe. -

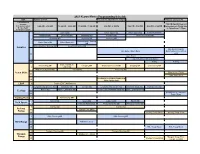

2021 Camp Keowa Master Programming Schedule

2021 Keowa Master Programming Schedule KEY Update: 2/17/21 ←Lunch 12:15pm/Siesta 1:00pm ←Dinner Lineup 5:45 I = instructional program 7:00 PM (Spirit Program) O = open program 9:00 AM - 9:50 AM 10:00 AM - 10:50 AM 11:00 AM - 11:50 AM 2:00 PM - 2:50 PM 3:00 PM - 3:50 PM 4:00 PM - 4:50 PM No program on Friday due B = bookable to Campfire at 7:30pm A = Adult Program BSA Guard Water Sports MB Water Sports MB Instructional Swim Swimming MB Swimming MB Swimming MB Kayaking MB Small Boat Sailing MB Lifesaving MB Kayaking MB Canoeing MB I Motor Boating / Rowing Water Sports MB Water Sports MB MB Aquatics Motor Boating / Rowing MB Small Boat Sailing MB Mile Swim/ Rowing Mile Swim (Thurs Only) Qualifications (Tues/Wed O only) Open Swim Open Boating (ends at 4:30pm) B Tubing Tubing Signs, Signals, & Geocaching MB Camping MB Wilderness Survival MB Camping MB Orienteering MB I Codes MB Wilderness Survival MB First Aid MB Pioneering MB Scout Skills Firem'n Chit (Thurs) O Totin' Chip (Tues) Introduction to Outdoor Leadership A Skills (Adults Only) LEAF I Project LEAF (AM Session) Envionmental Science MB Astronomy MB Forestry MB Environmental Science MB Mammal Study MB Plant Science MB I Ecology Nature MB Space Exploration MB Reptile and Amphibian Study MB Space Exploration MB Introduction to Leave No O Trace (Tues) Trading Post I Salemanship MB Fishing MB Sports MB Athletics MB Sports MB Field Sports I Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB Personal Fitness MB I Archery MB Archery MB Archery O Archery Free Shoot Range B Archery Troop Shoot Archery -

MS SCR 2016.Indd

MISSISSIPPI 2016 State Report Part of the America’s River Initiative The America’s River Initiative seeks to restore MAJOR SPONSOR REPORT the Lower Mississippi Alluvial Valley through Congratulations to the Mississippi State Campaign Committee! Th ey achieved habitat conservation, science and policy that Top 10 results in 2015! Led by Scott Forrest, Mississippi fi nished in a tie for 10th secures wintering, migration and breeding habitat place. Th eir accomplishments were impressive, including 16 new Life Sponsors, 12 for millions of waterfowl and reinforces the upgrades and 6 new Feather Society commitments. In addition, this team secured region’s rich waterfowling legacy. It also supports more than $265,000 in new cash to benefi t DU’s highest conservation priorities. conservation on the breeding grounds most Clearly, major sponsors in Mississippi are making a diff erence for the future of important to Mississippi Flyway waterfowl. Th e wetlands, waterfowl and waterfowl hunting. One such donor is Bobby America’s River Initiative is a crucial part of Ducks Massey, the Southern Region’s Unlimited’s Rescue Our Wetlands Campaign, a Director of Conservation seven-year, $2 billion eff ort aimed at changing the Services. A member of the face of conservation in North America. Rescue DU conservation staff , Bobby Our Wetlands is the largest wetlands and waterfowl has committed to becoming a conservation campaign in history. Diamond Life and Grand Slam Life Sponsor. Bobby grew up in the Mississippi Delta, and he knows well the importance of wetland conservation in the Magnolia State. “I believe in Ducks Unlimited. I work for DU and I know how dedicated this organization, its staff , sponsors and volunteers are to habitat conservation,” Bobby said.