The Inquisition and the Commedia Dell'arte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queen of Scots

Deux-Elles Music for the Queen of Scots The Flautadors Recorders and Drums in Scotland The role of the recorder in Scotland is very House, Berwickshire notes that she paid one similar to its use in England in that from me- Mr Crumbin for teaching her daughter the diaeval times it was employed at the court as recorder. The recorder was also listed as one a ‘soft’ instrument to provide entertainment of the instruments still being taught in the indoors during meals and special entertain- Aberdeen Sang Schule in 737. ments. In addition to a company of violaris, Mary, Queen of Scots was known to have The instruments used in this recording con- employed musicians (pyparis) who would sist of a matching consort made by Thomas have played recorder and other woodwind in- Prescott after existing 6th century recorders struments. A generation later, accounts of the in the Vienna Kunsthistorisches Museum. baptism of James VI’s first son, Henry, tell us that “a still noise of recorders and flutes” was Tabors, tambourines and finger cymbals heard. As well as bringing courtly pleasure, were ubiquitous in renaissance Europe but the recorder was ideal as a folk instrument and perhaps worthy of note is the high opinion no doubt this was in James Thomson’s mind held by Mary’s grandfather James IV of a when he compiled his book for the recorder black African drummer in his court. As well in 70. His publication gives us an idea of as paying for his drum to be finely painted, the popular tunes the recorder enthusiasts James spent a considerable amount of money of Edinburgh would have enjoyed playing on a horse for him and he gave many presents and, as well as Scots melodies and pieces by to his family. -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G. Phd, Mphil, Dclinpsychol) at the University of Edinburgh

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: • This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. • A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. • This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. • The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. • When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Desire for Perpetuation: Fairy Writing and Re-creation of National Identity in the Narratives of Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang Yuki Yoshino A Thesis Submitted to The University of Edinburgh for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English Literature 2013 Abstract This thesis argues that ‘fairy writing’ in the nineteenth-century Scottish literature serves as a peculiar site which accommodates various, often ambiguous and subversive, responses to the processes of constructing new national identities occurring in, and outwith, post-union Scotland. It contends that a pathetic sense of loss, emptiness and absence, together with strong preoccupations with the land, and a desire to perpetuate the nation which has become state-less, commonly underpin the wide variety of fairy writings by Walter Scott, John Black, James Hogg and Andrew Lang. -

Historical Memoirs of the Reign of Mary, Queen of Scots, and a Portion Of

NAllONAl. LIBRARY OFSGO'II.AN]) iiililiiiiililiiitiliiM^^^^^ LORD HERRIES' MEMOIRS. -A^itt^caJi c y HISTORICAL MEMOIRS OF THE REIGN OF MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS, AND A PORTION OF THE REIGN OF KING JAMES THE SIXTH. LOED HEERIES. PRINTED AT EDINBURGH. M.DCCC.XXXVI. EDINBinr.H rniNTING COMPANY. PRESENTED myt atiftot^fora €luh ROBERT PITCAIRN. ABROTSFORD CLUB, iMDCCCXXXVI. JOHN HOPE, EsQoiKE. Right Hon. The Earl of Aberdeen. Adam Anderson, Esquire. Charles Baxter, Esquire. 5 Robert Blackwood, Esquire. BiNDON Blood, Esquire. Beriah Botfield, Esquire. Hon. Henry Cockburn, Lord Cockburn. John Payne Collier, Esquire. 10 Rev. Alexander Dyce, B.A. John Black Gracie, Esquire. James Ivory, Esquire. Hon. Francis Jeffrey, Lord Jeffrey. George Ritchie Kinloch, Esquire. 15 William Macdowall, Esquire. James Maidment, Esquire. Rev. James Morton. Alexander Nicholson, Esquire. Robert Pitcairn, Esquire. 20 Edward Pyper, Esquire. Andrew Rutheefurd, Esquire. Andrew Shortrede, Esquire. John Smith, Youngest, Esquire. Sir Patrick Walker, Knight. 25 John Whitefoord Mackenzie, Esquire. ^fctftarg. William B. D. D. Turnbull, Esquire. PREFATORY NOTICE. The following historical Memoir lias been selected by the Editor as the subject of his contribution to The Abbotsford Club—as well from the consideration of the interesting, but still obscure, period of Scottish history to which it refers, and which it materially tends to illustrate in many minute parti- culars—as from the fact that the transcript, or rather abridg- ment, of the original j\IS. by Lord Herries, now belonging to the Faculty of Advocates, is nearly all that is known to have been preserved of the valuable historical Collections made by the members of the Scots College of Douay, which, unfortu- nately, appear to have been totally destroyed during the French Revolution. -

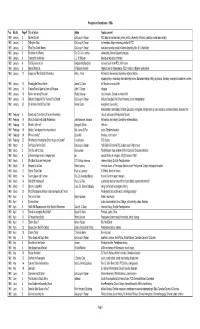

Presbyterian Record Index 1960S

Presbyterian Record Index - 1960s Year Month Page # Title of article Author Topics covered 1960 January 2 Nuclear Control DeCourcy H. Rayner PCC stand on nuclear arms, peace, politics, University of Toronto, pacifism, nuclear arms testing 1960 January 2 Telling the Story DeCourcy H. Rayner lost members, fringe members, potential of PCC 1960 January 2 What This Church Needs DeCourcy H. Rayner executive council proposal to General Assembly, Rev. Dr. A. Neil Miller 1960 January 3 Scrutinize the Offering Rev. Dr. A. A. Lowther stewardship, General Assembly budgets 1960 January 4 Training for the Ministry J. L. W. McLean theological education, ministers 1960 January 6 The Big Issues of Life Margaret MacNaughton survey of youth in the PCC, faith issues 1960 January 8 Nigeria Wants Us R. Malcolm Ransom Nigeria's year of independence, PCC's mission to Nigeria, missionaries 1960 January 10 Europe and The Scottish Reformation Allan L. Farris Reformation Anniversary Committee, reformed history equipping laity in missionary and ministering service, European training of laity, lay training, Germany, evangelical academies, centres 1960 January 13 Breaking the Silence Barrier James S. Clarke for Christian community life 1960 January 14 Canada Should Open its Doors to Refugees John C. Cooper refugees 1960 January 15 Famine not merely Financial Walter Donovan church decline, Canada as mission field 1960 January 18 Malcolm Campbell's Fifty Years at First Church DeCourcy H. Rayner Malcolm Campbell, First Church Montreal, church amalgamation 1960 January 30 St. Andrew's Has Its Face Lifted Roman Collar evangelism, soul-saving administration, stewardship, Christian Education, evangelism, full-time service, home missions, overseas missions, women of the 1960 February 5 Boards and Committees (of General Assembly) church, audio-visual, Presbyterian Record 1960 February 16 What We Owe the Scottish Reformation John Alexander Johnston Reformation Anniversary Committee, reformed history 1960 February 18 What's in it for me? George H. -

Download Download

CONTENTS OF APPENDIX. Page I. List of Members of the Society from 1831 to 1851:— I. List of Fellows of the Society,.................................................. 1 II. List of Honorary Members....................................................... 8 III. List of Corresponding Members, ............................................. 9 II. List of Communications read at Meetings of the Society, from 1831 to 1851,............................................................... 13 III. Listofthe Office-Bearers from 1831 to 1851,........................... 51 IV. Index to the Names of Donors............................................... 53 V. Index to the Names of Literary Contributors............................. 59 I. LISTS OF THE MEMBERS OF THE SOCIETY OF THE ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND. MDCCCXXXL—MDCCCLI. HER MAJESTY THE QUEEN, PATRON. No. I.—LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. (Continued from the AppenHix to Vol. III. p. 15.) 1831. Jan. 24. ALEXANDER LOGAN, Esq., London. Feb. 14. JOHN STEWARD WOOD, Esq. 28. JAMES NAIRWE of Claremont, Esq., Writer to the Signet. Mar. 14. ONESEPHORUS TYNDAL BRUCE of Falkland, Esq. WILLIAM SMITH, Esq., late Lord Provost of Glasgow. Rev. JAMES CHAPMAN, Chaplain, Edinburgh Castle. April 11. ALEXANDER WELLESLEY LEITH, Esq., Advocate.1 WILLIAM DAUNEY, Esq., Advocate. JOHN ARCHIBALD CAMPBELL, Esq., Writer to the Signet. May 23. THOMAS HOG, Esq.2 1832. Jan. 9. BINDON BLOOD of Cranachar, Esq., Ireland. JOHN BLACK GRACIE, Esq.. Writer to the Signet. 23. Rev. JOHN REID OMOND, Minister of Monfcie. Feb. 27. THOMAS HAMILTON, Esq., Rydal. Mar. 12. GEORGE RITCHIE KINLOCH, Esq.3 26. ANDREW DUN, Esq., Writer to the Signet. April 9. JAMES USHER, Esq., Writer to the Signet.* May 21. WILLIAM MAULE, Esq. 1 Afterwards Sir Alexander W. Leith, Bart. " 4 Election cancelled. 3 Resigned. VOL. IV.—APP. A 2 LIST OF FELLOWS OF THE SOCIETY. -

Dominican Martyrs of Great Britain

Providence College DigitalCommons@Providence Historical Catholic and Dominican Documents Special Collections 1912 Dominican Martyrs of Great Britain Fr. Raymond Devas, O.P. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/catholic_documents Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, European History Commons, and the History of Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Devas, O.P., Fr. Raymond, "Dominican Martyrs of Great Britain" (1912). Historical Catholic and Dominican Documents. 15. https://digitalcommons.providence.edu/catholic_documents/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at DigitalCommons@Providence. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Catholic and Dominican Documents by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Providence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOMINICAN MARTYRS OF GREAT BRITAIN DOMINICAN MARTYRS OF GREAT BRITAIN 'IA!btl obstat FR. PLACID CONWAY, O.P., S.T.M. FR. BEDE JARRETT, O.P., S.T.L., M.A. BY 5mprtmatur FR. RAYMUND DEV AS, O.P. FR. HUMBERT EVEREST, O.P., S.T.B., Prior Provindalis 1RfbU obstat FR. OSMUND COONEY, O.F.M. , Censor lJeputatus 5mprfmatur EDM. CAN. SURMONT, Vic. gen. WESTMONASTERII, die 2 Novembris Ign. BURNS & OATES 28 ORCHARD STREET, LONDON, W. 191'2 SONN !WELL COLLECTION , I I I FOREWORD THE Contents-page by itself is almost sufficient introduction to this little book. The author's aim has been simply to give an account, short but as far as possible complete, of three Dominicans who laid down their lives for the Faith in Great Britain. The name of one of these is already on the list of those English Martyrs who have been declared Venerable : will it be too much to hope that the following pages may lead towards the Beatification of all three? In every country and in every age the white habit of Saint Dominic has been decked with the blood of Martyrs; and it is but natural for us to wish that due honour may be paid to those of our own nation, who for God's sake gave up their bodies to sufferings and to death itself. -

Black Family

WILLS It is further my will and desire that my negro man Peter divided between my children as follows, Charles Back, John shall and hereby given my razor and shaving tools except Back, Thomas W. Back, Patience Cooper, Elender Loyd, my hone that I give to my son Thomas Back. In testimony Elizabeth Higginbotham and it further my will that my two whereof I have subscribed my name and affixed my seal on grand daughters Elizabeth Andrew and Sally Cooper shall the 18th day of December eighteen hundred and thirty jointly have one share of my money equally with my own nine. ? children above named the foregoing I mean to include all Samuel Rector Jacob Back SEAL money on hand and all money which may be coming to me William BramJl1er and it is to be divided after my death as soon as it can be Commonwealth of Kentucky Wayne County Court Set. collected provide thaough subject to the following condition, whereas my grand daughter Martha Back claims I, William Simpson, Clerk of the County Court for the a debt against me for her company staying with me for County aforesaid do certify that the foregoing last will and which I don't consider I owe her a cent for. I consider her testament of Jacob Back, deed which appears from the claim unjust and if my said granddaughter Martha Back record of the Wayne County Court to have been proven at should recover anything for her claim that which shy may the January Court 1840 in open court by the oath of recover or any body for lier that which she recovers shall be Samuel Rector and William Brammer subscribing witnesses my son Charles Back portion of the aforesaid money or if thereto has been duly recorded in my office agreeably to an there should be any suit brought against the estate or m~ on order of said county court made pursuant to an act entitled account of the claim, it is my will that my son Charles Back to authorize certain records of the Wayne County Court to shall not have any part of my money but if there is no more be transcribed. -

MOORE, JOSEPH S., Ph.D. Irish Radicals, Southern Conservatives: Slavery, Religious Liberty and the Presbyterian Fringe in the Atlantic World, 1637-1877

MOORE, JOSEPH S., Ph.D. Irish Radicals, Southern Conservatives: Slavery, Religious Liberty and the Presbyterian Fringe in the Atlantic World, 1637-1877. (2011) Directed by Robert M. Calhoon. pp. 488 This dissertation is a study of Covenanter and Seceder Presbyterians in Scotland, Ireland and the American South from 1637-1877. Correspondence, diaries, political pamphlets, religious tracts, and church disciplinary records are used to understand the cultural sensibility, called herein the Covenanter sensibility, of the Covenanter movement. The dissertation examines how the sensibility was maintained and transformed by experiences such as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, the Glorious Revolution, the 1798 Irish Rebellion, the American Civil War, and Reconstruction. Critical issues involved are the nature of religious and political culture, the role of moderation and religious extremism, the nature of Protestant primitivsm and church discipline, and the political nature of radical Protestant religion. This dissertation looks at Covenanter movements broadly and eschews an organiZational history in favor of examining political and religious culture. It labels the broad groups within the Covenanter movement the Presbyterian fringe. In Scotland, the study examines Covenanter ideology, society, church discipline, cell group networks of praying societies, issues of legal toleration and religious liberty, the birth of the Seceder movement and anti-slavery rhetoric. In Ireland it examines the contested legal role of Presbyterian marriages, the controversial arrival of Seceders in Ireland, as well as Covenanters’ involvement in the Volunteer movement, the United Irishmen, and the 1798 Irish Rebellion. In America it studies the life of John Hemphill, the retention of exclusive psalm singing and primitive Protestantism, the American ColoniZation society in South Carolina, interracial religious transfers, and Reconstruction. -

Religion in Dundee and Haddington C.1520-1565

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2014 Civil Reformations: Religion in Dundee and Haddington C.1520-1565 Timothy Slonosky University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Religion Commons Recommended Citation Slonosky, Timothy, "Civil Reformations: Religion in Dundee and Haddington C.1520-1565" (2014). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1446. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1446 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1446 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Civil Reformations: Religion in Dundee and Haddington C.1520-1565 Abstract ABSTRACT CIVIL REFORMATIONS: RELIGION IN DUNDEE AND HADDINGTON, C.1520-1565 Timothy Slonosky Prof. Margo Todd In 1559-60, Scotland's Catholic church was dramatically and rapidly replaced by a rigorous Protestant regime. Despite their limited resources, the Protestant nobles who imposed the Reformation faced little resistance or dissent from the Scottish laity. A study of burgh records demonstrates that the nature of urban religion was crucial to the success of the Reformation among the laity. The municipal governments of Dundee and Haddington exercised significant control over religious worship in their towns, as they built and administered churches, hired clergy and provided divine worship as a public good. Up until 1560, the town councils fulfilled their esponsibilitiesr diligently, maintaining good relations with the clergy, ensuring high standards of service and looking for opportunities to expand public worship. The towns nonetheless acted to protect those who were interested in discussing religious reform. -

The Spirituali Movement in Scotland Before the Reformation of 1560 D

Scottish Reformation Society Historical Journal, 8 (2018), 1-43 ISSN 2045-4570 The spirituali movement in Scotland before the Reformation of 1560 D. W. B. Somerset 1. Introduction he spirituali were members of the Church of Rome in Italy in the Tearlier sixteenth century who held Lutheran or semi-Lutheran views on the doctrine of justifcation by faith but who remained within the bounds of Romanism. Te spirituali movement was a broad one, ranging from crypto-Protestants or Nicodemites,1 at one extreme, to those who believed in the sacrifce of the mass and who were ready to persecute Protestants, at the other. Te movement was strong in the 1530s and 1540s and included several cardinals such as Fregoso, Contarini, Sadoleto, Bembo, Seripando, Pole, and Morone. Twice (Pole in 1549 and Morone in 1565), a spirituali cardinal was almost elected as Pope. Te spirituali movement was bitterly opposed by the zelanti in the Church of Rome; and the setting up of the Roman Inquisition in 1542 was partly aimed at the suppression of the spirituali. Te foremost zelanti were Carafa, who was Pope Paul IV from 1555 to 1559, and Michele Ghislieri, who was Pope Pius V from 1566 to 1572.2 1. Te term ‘Nicodemite’ was introduced by Calvin to describe those of Protestant beliefs in France and Italy in the 1540s who chose to remain in the Church of Rome to avoid persecution; see C. M. N. Eire, War Against the Idols, (Cambridge, 1986), p. 236. Similar conduct was found soon aferwards in Germany (following the Augsburg Interim of 1548) and in England (during the reign of Mary I, 1553-58). -

THE ART of MUSIC in GB-Lbl Add. MS 4911: a CASE for ROBERT CARVOR AS the ANONYMOUS SCOT

ABSTRACT Title of Thesis: THE ART OF MUSIC IN GB-Lbl Add. MS 4911: A CASE FOR ROBERT CARVOR AS THE ANONYMOUS SCOT Debra Marion Livant Nakos, Master of Arts, 2020 Thesis directed by: Professor Barbara H. Haggh-Huglo Department of Music GB-Lbl Add. MS 4911, the sole source of an anonymous music treatise, The Art of Music, is among the few manuscripts to have survived the Scottish Reformation. In answer to the puzzle of its authorship, masters of song schools in Edinburgh or Aberdeen have been proposed. A new reading of the text places the date of its creation between 1559 and 1567 and leads to a revised profile of the author, which, as is demonstrated here, the Scottish composer Robert Carvor (1487/8 – c. 1568) uniquely matches. Further supporting Carvor as the author of the treatise is its inclusion of a section of Carvor’s Missa L’homme armé and of a caricature strikingly similar to one found in the Carvor Choirbook (GB-En MS Adv. 5.1.15), where Carvor’s compositions bear his signature. An Appendix includes the first English translation of the rules of faburden, which are unique to The Art of Music (f.94r-f.112r). THE ART OF MUSIC IN GB-Lbl Add. MS 4911: A CASE FOR ROBERT CARVOR AS THE ANONYMOUS SCOT By Debra Marion Livant Nakos Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts 2020 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara H. -

First Families Is a Collection of Genealogical Information Taken from Various Sources That Were Periodically Submitted to the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick

NOTE: First Families is a collection of genealogical information taken from various sources that were periodically submitted to the Provincial Archives of New Brunswick. The information has not been verified against any official records. Since the information in First Families is contributed, it is the responsibility of those who use the information to verify its accuracy. Mc’s and Mac’s are arranged alphabetically by the letter after the letter “c”. MCADAM: Alexander McAdam b. 1815 in Ireland, d. 1883, m. Margaret Adams born 1826 in Ireland, d. 1912: both came to NB in 1826 according to the 1851 census: they settled in Fredericton, York County: Children mentioned: 1) Martha McAdam: 2) Matilda Jane McAdam b. 15 Sep 1844: 3) Margaret Annie McAdam b. 1846, d. 1943: 4) Mary C. McAdam b. 1848: 5) Eliza Ida McAdam b. 1850, d. 1943: 6) James A. McAdam born 1853, d. 1944: 7) John McAdam b. 1857, d. 1938: 8) Mary Louise McAdam b. 1861, d. 1926: 9) Harry McAdam born 1863, d. 1911: 10) Frank McAdam b. 1867, d. 1958. Source: MC80/644 Isabel L. Hill’s The old burying ground Fredericton, NB, Volume I, pages 23 to 25 which notes that Alexander came from Galashiels in Selkirkshire, Scotland: the 1851 and 1861 York County census, however, says that he was born in Ireland. MCADAM: John McAdam b. 28 Mar 1807 in County Antrim, Ireland, died 13 Mar 1893: came to NB in 1817 and settled at St. Stephen, Charlotte County: married 19 Apr 1835 Jane Ann Murchie b. 10 Apr 1816, d.