The Advantage of Having a Female Partner: Some Reflections on Fourteenth Amendment Equal Protection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phenomenological Claim of First Sexual Intercourse Among Individuals of Varied Levels of Sexual Self-Disclosure

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 2005 Phenomenological claim of first sexual intercourse among individuals of varied levels of sexual self-disclosure Lindsey Takara Doe The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Doe, Lindsey Takara, "Phenomenological claim of first sexual intercourse among individuals of varied levels of sexual self-disclosure" (2005). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 5441. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/5441 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Maureen and Mike MANSFIELD LIBRARY The University of Montana Permission is granted by the author to reproduce this material in its entirety, provided that this material is used for scholarly purposes and is properly cited in published works and reports. **Please check "Yes" or "No" and provide signature Yes, I grant permission ___ No, I do not grant permission ___ Author's Signature: Date: ^ h / o 5 __________________ Any copying for commercial purposes or financial gain may be undertaken only with the author's -

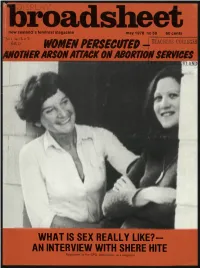

AN INTERVIEW with SHERE HITE Registered at the GPO, Wellington, As a Magazine Fronting Up

D iS P i A Y new Zealand’s feminist magazine may 1978 no 59 60 cents | -3<M q-iXoS 0& D WOMEN PERSECUTED 4 TUCiCRS CCI1EGES MOTHER ARSON ATTACK ON ABORTION SERVICES «LAND WHAT IS SEX REALLY LIKE?— AN INTERVIEW WITH SHERE HITE Registered at the GPO, Wellington, as a magazine Fronting up Office Wanted if you could send us the extra money. You don’t have to, but it would help Office hours for Broadsheet are: More advertisements for Broadsheet. a lot! Mon — Thurs: 9 a.m. — 3 p.m. Readers are beginning to make more Friday: 9 a.m. — 12 noon. use of our very reasonable Classified Now you see it, now you It is best to ring first before visiting as Advertisements service (roughly 5 cents don’t we are sometimes out and about. per word) and we hear that most of There are sometimes people here our advertisers get a good response. So Or — The Great Disappearing Trick. after 3 p.m. too. if you need a flat, a flatmate, a Job, “Ladies and ladies . .” (InterJection: a workmate, a travelling companion — “Women!”) “ . in my right hand I Phone: 378-954. or if you’ve got something to sell — have a book marked Broadsheet. Address: 65 Victoria St. West, City remember that Broadsheet is a good Abracadabra, hocus pocus, — now (Just above Albert St.). place to advertise. Please let our where is it?” Mystified silence. Non advertisers know that you saw their comprehension on the part of the Broadsheet Benefit ad. in Broadsheet, and if you can Collective — where do our precious persuade any (non-sexist) businesses to magazines and books get to? We have A multi-media women’s show has been advertise with us we’d be delighted. -

An Economic Model of the Rise in Premarital Sex and Its De-Stigmatization

NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES FROM SHAME TO GAME IN ONE HUNDRED YEARS: AN ECONOMIC MODEL OF THE RISE IN PREMARITAL SEX AND ITS DE-STIGMATIZATION Jesús Fernández-Villaverde Jeremy Greenwood Nezih Guner Working Paper 15677 http://www.nber.org/papers/w15677 NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH 1050 Massachusetts Avenue Cambridge, MA 02138 January 2010 Guner acknowledges support from European Research Council (ERC) Grant 263600. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic Research. NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer- reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official NBER publications. © 2010 by Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, Jeremy Greenwood, and Nezih Guner. All rights reserved. Short sections of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full credit, including © notice, is given to the source. From Shame to Game in One Hundred Years: An Economic Model of the Rise in Premarital Sex and its De-Stigmatization Jesús Fernández-Villaverde, Jeremy Greenwood, and Nezih Guner NBER Working Paper No. 15677 January 2010, Revised January 2012 JEL No. E1,E13,J10,J13,N0,O11,O33 ABSTRACT Societies socialize children about sex. This is done in the presence of peer-group effects, which may encourage undesirable behavior. Parents want the best for their children. Still, they weigh the marginal gains from socializing their children against its costs. Churches and states may stigmatize sex, both because of a concern about the welfare of their flocks and the need to control the cost of charity associated with out-of-wedlock births. -

25 Years of Commitment to Sexual Health and Education

SIECUS in 1989 SECUS: 25 Years of Commitment To Sexual Health and Education Debra W. Haffner, MPH Executive Director wenty-five years ago, a lawyer, a sociologist, a clergyman, individual life patterns asa creative and recreativeforce.” In T a family life educator, a public health educator, and a many ways, the missiontoday remains true to those words. physician came together to form the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States. In the words of In January 1965, SIECUS held a national pressconference SIECUS cofounder and first executive director, Dr. Mary S. announcing its formation. In a New York Herald Tribune Calderone, “the formation of SIECUS in 1964 was not the story, Earl Ubell, who later joined the SIECUS Board of creation of something new so much as the recognition of Directors, wrote, ‘! . the group’s first action has been most something that had existed for a long time: the desire of noteworthy. It formed.” A month later, SIECUS published its many people of all ages and conditions to comprehend what first newsletter, with an annual subscription rate of $2.00! sex was all about, what old understandings about it were still valid, what new understandings about it were needed, where The mid-1960swere important years for advancing sexual it fit in a world that was changing, and between men and rights. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 wascritical in establish- women who were changing.” ing principles of racial and sexual equity. In 1965, the Supreme Court decided Griswoldv. Connecti&, which I have had the pleasure of reading the first SIECUS news- establishedthe constitutional right to privacy and gave letters; all of the minutes from years of meetings of the married women the right to contraception. -

ORGASM IS GENDERED a Feminist Exploration Into the (Hetero) Sexual Lives of Young

ORGASM IS GENDERED a feminist exploration into the (hetero) sexual lives of young women Lorenza Mazzoni ORGASM IS GENDERED a feminist exploration into the (hetero) sexual lives of young women Lorenza Mazzoni Supervisor Teresa Ortiz. Universidad de Granada Co-supervisor Rosemarie Buikema. Universiteit Utrecht Erasmus Mundus Master’s Degree in Women’s and Gender Studies Instituto de Estudios de la Mujer. Universidad de Granada. 2010/2011 ORGASM IS GENDERED a feminist exploration into the (hetero) sexual lives of young women Lorenza Mazzoni Supervisor Teresa Ortiz. Universidad de Granada Co-supervisor Rosemarie Buikema. Universiteit Utrecht Erasmus Mundus Master’s Degree in Women’s and Gender Studies Instituto de Estudios de la Mujer. Universidad de Granada. 2010/2011 Firma de aprobación………………………………………….. ABSTRACT Italian society is still facing an enormous “orgasm gap” in (hetero) sexual relations: according to a very recent survey (Barbagli and co., 2010) only a minority of women reach an orgasm in every sexual intercourse, in contrast with the vast majority of men; this is true even in the younger generations. I take the lack of orgasm as a starting point for studying how sexual behaviours are still under the reign of patriarchy, imposing male standards that privilege male pleasure at the expense of female. My research therefore aims to analyze from a feminist perspective the agency of young women in reaching an orgasm during a (hetero) sexual relation. Through the use of a “feminist objectivity” and a qualitative methodology I have conducted eight semi-structured in-depth interviews with young women in Bologna, Italy. In particular I have identified a series of widespread social discourse that prevent women from choosing orgasm, while causing them to live their sexuality with high doses of insecurity and inhibition. -

In the Habit of Being Kinky: Practice and Resistance

IN THE HABIT OF BEING KINKY: PRACTICE AND RESISTANCE IN A BDSM COMMUNITY, TEXAS, USA By MISTY NICOLE LUMINAIS A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY WASHINGTON STATE UNIVERSITY Department of Anthropology MAY 2012 © Copyright by MISTY NICOLE LUMINAIS, 2012 All Rights Reserved © Copyright by MISTY NICOLE LUMINAIS, 2012 All rights reserved To the Faculty of Washington State University: The members of the Committee appointed to examine the dissertation of MISTY NICOLE LUMINAIS find it satisfactory and recommend that it be accepted. ___________________________________ Nancy P. McKee, Ph.D., Chair ___________________________________ Jeffrey Ehrenreich, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Faith Lutze, Ph.D. ___________________________________ Jeannette Mageo, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could have not completed this work without the support of the Cactus kinky community, my advisors, steadfast friends, generous employers, and my family. Members of the kinky community welcomed me with all my quirks and were patient with my incessant questions. I will always value their strength and kindness. Members of the kinky community dared me to be fully present as a complete person rather than relying on just being a researcher. They stretched my imagination and did not let my theories go uncontested. Lively debates and embodied practices forced me to consider the many paths to truth. As every anthropologist before me, I have learned about both the universality and particularity of human experience. I am amazed. For the sake of confidentiality, I cannot mention specific people or groups, but I hope they know who they are and how much this has meant to me. -

The Joy of Sex Ed

Older, Wiser, Sexually Smarter: 30 Sex Ed Lessons for Adults Only IT’S HISTORY! 25,000 Years of Sexual Aids with Carole Adamsbaum, RN, MA* OBJECTIVES Participants will: 1. Recognize the long history of the development and use of sexual aids. 2. Identify the many ways people need new physical supports as they age. 3. Describe the reasons people choose to use sexual aids. 4. Evaluate three types of sexual aids and their contribution to sexual health. RATIONALE Sexual aids, also known as “sex toys” can enable the enjoyment of sexual pleasure and support the sexual health of people as they age. Some people, especially older people, are unaware of the potential benefits of these products. Others lack an understanding of their use and have a discomfort with the idea of “sex toys”. The activities in this lesson demonstrate how aids have been used through human history and can help to people feel comfortable deciding whether or not aids would enhance their own sexual lives. MATERIALS Easel paper/board, markers, tape, and pencils Handout: ENHANCING SEX THROUGHOUT HISTORY Handout: SEX TOY MYTHS PROCEDURE 1. After reviewing the ground rules, note that throughout history people have used a variety of devices to enhance their sexual experience. But, before we look at that history, let’s think about other ways people use a variety of technical supports to deal with their changing bodies as they age. * Carole Adamsbaum, RN, MA is a retired sexuality educator in New Jersey. © 2009 by The Center for Family Life Education www.SexEdStore.com Older, Wiser, Sexually Smarter: 30 Sex Ed Lessons for Adults Only 2. -

“Joy” of Sex Really For?: a Queer Critique of Popular Sex Guides

1 Who is the “Joy” of Sex Really For?: A Queer Critique of Popular Sex Guides Anna Naden Feminist and Gender Studies Colorado College Bachelor of Arts Degree in Feminist and Gender Studies May 2015 2 Abstract Using The Guide to Getting It On and The Joy of Sex, this paper explores the ways in which sex guides address queer identities. The arguments presented rely on queer theory, particularly the work of Annamarie Jagose and Eve Sedgewick, to understand queer as an unstable and dynamic category of identity. The paper then turns to The Guide to Getting It On and The Joy of Sex to examine how sex guides uphold hegemonic standards of heterosexuality and whiteness and further marginalize queer identities and people of color, arguing that sex guides cannot account for queer identities and are inherently exclusionary even when they aim to be inclusive. Keywords: sex guide, queer theory, heterosexuality, whiteness, queer identities 3 Who is the “Joy” of Sex Really For?: A Queer Critique of Popular Sex Guides Introduction In the preface to The Joy of Sex (2009: 8), Susan Quilliam writes: “Joy was not only a product of the [sexual] revolution, it also helped create it… The text and illustrations were designed to both reassure the reader that their sexuality was normal and to offer further possibilities with which to expand their sexual menu.” Who defines “normal,” and what does this imply for those of us who do not see ourselves reflected in the text and illustrations? Reading The Guide to Getting It On as an undergraduate was an unexpectedly harsh experience for me; I found myself continually frustrated with the book’s flippant treatment of and exclusion of genders and sexualities outside of the realm of white, cisgender heterosexuality. -

Celebrating Masters & Johnson's Human Sexual Response: A

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 53 WashULaw’s 150th Anniversary 2017 Celebrating Masters & Johnson’s Human Sexual Response: A Washington University Legacy in Limbo Susan Ekberg Stiritz Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. Louis Susan Frelich Appleton Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Legal Biography Commons, Legal Education Commons, Legal History Commons, and the Sexuality and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Susan Ekberg Stiritz and Susan Frelich Appleton, Celebrating Masters & Johnson’s Human Sexual Response: A Washington University Legacy in Limbo, 53 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 071 (2017), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol53/iss1/12 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Celebrating Masters & Johnson’s Human Sexual Response: A Washington University Legacy in Limbo Susan Ekberg Stiritz Susan Frelich Appleton There are in our existence spots of time, Which with distinct pre-eminence retain A renovating Virtue . by which pleasure is enhanced.1 INTRODUCTION Celebrating anniversaries reaffirms2 what nineteenth-century poet William Wordsworth called “spots of time,”3 bonds between self and community that shape one’s life and create experiences that retain their capacity to enhance pleasure and meaning.4 Marking the nodal events of institutions, in particular, fosters awareness of shared history, strengthens institutional identity, and expands opportunities and ways for members to belong.5 It comes as no surprise, then, that Associate Professor of Practice & Chair, Specialization in Sexual Health & Education, the Brown School of Social Work, Washington University in St. -

The 15-Minute Orgasm

The 4-Hour Body AN UNCOMMON GUIDE TO RAPID FAT-LOSS, INCREDIBLE SEX, AND BECOMING SUPERHUMAN Timothy Ferriss CROWN ARCHETYPE NEW YORK !"##$%&'()(&*+)+)($*,$-.$#/01233444511 /(6/76/(44478))49: For my parents, who taught a little hellion that marching to a different drummer was a good thing. I love you both and owe you everything. Mom, sorry about all the crazy experiments. Support good science— 10% of all author royalties are donated to cure- driven research, including the excellent work of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. !"##$%&'()(&*+)+)($*,$-.$#/0123344415 /(6/76/(44478))49: CONTENTS START HERE Thinner, Bigger, Faster, Stronger? How to Use This Book 2 FUNDAMENTALS— FIRST AND FOREMOST The Minimum Effective Dose: From Microwaves to Fat- Loss 17 Rules That Change the Rules: Everything Popular Is Wrong 21 GROUND ZERO—GETTING STARTED AND SWARAJ The Harajuku Moment: The Decision to Become a Complete Human 36 Elusive Bodyfat: Where Are You Really? 44 From Photos to Fear: Making Failure Impossible 58 SUBTRACTING FAT BASICS The Slow- Carb Diet I: How to Lose 20 Pounds in 30 Days Without Exercise 70 The Slow- Carb Diet II: The Finer Points and Common Questions 79 Damage Control: Preventing Fat Gain When You Binge 100 The Four Horsemen of Fat- Loss: PAGG 114 !"##$%&'()(&*+)+)($*,$-.$#/012334445 /(6/76/(44478))49: CONTENTS xi ADVANCED Ice Age: Mastering Temperature to Manipulate Weight 122 The Glucose Switch: Beautiful Number 100 133 The Last Mile: Losing the Final 5–10 Pounds 149 ADDING MUSCLE Building the Perfect Posterior (or Losing 100+ -

Are Women Bad at Orgasms? Understanding the Gender Gap by Lisa Wade, Phd

Are Women Bad at Orgasms? Understanding the Gender Gap By Lisa Wade, PhD DISCLOSURE This draft may not match the final draft. CITATION Wade, Lisa. 2015. Are Women Bad at Orgasms? Understanding the Gender Gap. Pp. 227-237 in Gender, Sex, and Politics: In the Streets and Between the Sheets in the 21st Century, edited by Shira Tarrant. New York: Routledge. ABSTRACT Women who have sex with men have about one orgasm for every three her partner enjoys. We call this the “orgasm gap,” a persistent average difference in the frequency of orgasm for men and women who have heterosexual sex. In this paper, I discredit one common explanation for this gap—the idea that women are somehow bad at orgasms—and offer alternative explanations for the gendered asymmetry in this one type of sexual pleasure: a lack of knowledge, the de- prioritization of female sexual pleasure, sexual objectification and self-objectification, and the coital imperative in the sexual script. 1 Are Women Bad at Orgasms? Understanding the Gender Gap By Lisa Wade, PhD Women who have sex with men have about one orgasm for every three her partner enjoys.i We call this the “orgasm gap,” a persistent average difference in the frequency of orgasm for men and women who have heterosexual sex. I want to discredit one common explanation for this gap—the idea that women are somehow bad at orgasms—and offer alternative explanations for the gendered asymmetry in this one type of sexual pleasure. The common cultural narrative about men’s orgasms is that, if anything, they arrive too easily and too quickly. -

Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality Gayle S

CHAPTER 9 Thinking Sex: Notes for a Radical Theory of the Politics of Sexuality Gayle S. Rubin The Sex Wars ‘Asked his advice, Dr. J. Guerin affirmed that, after all other treatments had failed, he had succeeded in curing young girls affected by the vice of onanism by burning the clitoris with a hot iron . I apply the hot point three times to each of the large labia and another on the clitoris . After the first operation, from forty to fifty times a day, the number of voluptuous spasms was reduced to three or four . We believe, then, that in cases similar to those submitted to your consideration, one should not hesitate to resort to the hot iron, and at an early hour, in order to combat clitoral and vaginal onanism in the little girls.’ (Zambaco, 1981, pp. 31, 36) The time has come to think about sex. To some, sexuality may seem to be an unimportant topic, a frivolous diversion from the more critical problems of poverty, war, disease, racism, famine, or nuclear annihilation. But it is precisely at times such as these, when we live with the possibility of unthinkable destruction, that people are likely to become dangerously crazy about sexuality. Contemporary conflicts over sexual values and erotic conduct have much in common with the religious disputes of earlier centuries. They acquire immense symbolic weight. Disputes over sexual behaviour often become the vehicles for displacing social anxieties, and discharging their attendant emotional intensity. Consequently, sexuality should be treated with special respect in times of great social stress. The realm of sexuality also has its own internal politics, inequities, and modes of oppression.