An Evaluative Biography of Cynical Realism and Political Pop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zeng Fanzhi Posted: 12 Oct 2011

Time Out Hong Kong October 12, 2011 GAGOSIAN GALLERY Zeng Fanzhi Posted: 12 Oct 2011 With his psychologically complex portraits, Zeng Fanzhi has established himself as one of the greatest painters of his generation. Edmund Lee talks to the Chinese artist during his Hong Kong visit. When people think about Zeng Fanzhi, they often recall his painting subjects’ white masks, their outsized hands and the astonishingly high prices that these hands have been fetching in auctions. In person, the Beijing-based 47-year-old artist whose impressionistic portraits of seemingly suppressed emotions is himself rather serene. Zeng only sporadically breaks into very subdued chuckles when our conversation drifts on to his slightly awkward status as one of the world’s top-selling artists, which, at a 2008 auction, saw his oil-on-canvas diptych Mask Series 1996 No.6 sold for US$9.7 million, a record for Asian contemporary art. Drawn from the inner struggles stemming from the self-confessed introvert’s city living experiences, Zeng’s Mask Series – which he started in 1994 and officially concluded in 2004, and is generally considered his most important series to date – also delves into the artist’s childhood memories amid the socialist influences that he grew up with in the 1970s. We meet up with the artist at his Hong Kong exhibition, which provides a fascinating survey of a career that’s equally characterised for its many stages of reinvention. I can imagine that you must be a very busy man. So how much time in a day do you normally devote to painting? I usually spend about 80 to 90 percent of my time creating. -

Art: China ‑ WSJ.Com

7/12/12 Art: China ‑ WSJ.com Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, noncommercial use only. To order presentationready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now WEEKEND JOURNAL November 17, 2007 PICKS Art: China With new Chinese works hot at auction, galleries and museums join the action By LAUREN A.E. SCHUKER On the auction block this week, Chinese contemporary art set records, with some works selling for nearly $5 million. Works by a number of the same artists, including Yang Shaobin, Yue Minjun and Zhang Xiaogang, are also on display and on sale this month at a variety of U.S. galleries and museums. Below, three New York shows featuring contemporary Chinese artists this month. Eli Klein Fine Art 'China Now: Lost in Transition' On view Nov. 17 through Jan. 15 The SoHo gallery opens its second major show today, featuring works by 13 Chinese contemporary artists, such as 20something Zhang Peng, that director Rebecca Heidenberg handpicked during a trip to Beijing. Arario Gallery 'Absolute Images II' Nov. 10 through Jan. 13 The inaugural show for the gallery's New York space features 11 artists from Beijing and Shanghai, including abstract painter Yang Shaobin (left) and symbolistsurrealist Zhang Xiaogang. The works sell for up to $1 million, and some, such as Mr. Yang's "Blood Brothers" series, are so fresh that "the paint isn't even dry yet," according to director Jane Yoon. -

The Two Cultures of China Today

11 19 Bergos Berenberg Art Consult The Two Cultures of China today Several years ago, the great Swiss writer Thomas Hürlimann wrote that there were two speeds in his country. It was clear what he meant, as not all parts of Switzerland could keep pace with the cities’ accelerated commerce, swift traffic and advancing industrialization. In China today, top speed is increasingly the only speed in evidence. As a result, the country is explosively developing into a world consisting of two cultures. Both cultures are grounded in rapid growth, in WeChat, fifteen-second video clips, countless games and game con- soles. There is an enormous amount of production, communication, and consumption in China, and the concomitant, seemingly unbridled domestic trade, according to Alibaba as the motor of China’s perpetually booming E-commerce, is now exceeding many billions of Yuan per day. More than other nations, the Chinese are astonishingly diligent and focused. The constant maxi- mal investment of energy awakens endorphins: it is fun. This is the context in which the West Bund Group in Shanghai has managed not only to work around Fang Lijun: 1995.1 the meritorious Yuz Museum founded by the entrepreneur Budi Tek and the 1995, Oil on canvas similarly high-quality, also private Long Museum founded by Wang Wei and her 70 × 116 cm husband Liu Yiqian, but also to promote an art market that has since manifest- ed itself in two fairs. West Bund Art & Design, along with the somewhat older Art021, represent the first of the two cultures. The entire West Bund area in Shanghai is now the brilliant pinnacle of a seemingly boundless Chinese consumer culture. -

Contemporary Art Market 2011/2012 Le Rapport Annuel Artprice Le Marché De L'art Contemporain the Artprice Annual Report

CONTEMPORARY ART MARKET 2011/2012 LE RAPPORT ANNUEL ARTPRICE LE MARCHÉ DE L'ART CONTEMPORAIN THE ARTPRICE ANNUAL REPORT LES DERNIÈRES TENDANCES - THE LATEST TRENDS / L’ÉLITE DE L’A RT - THE ART ELITE / ART URBAIN : LA RELÈVE - URBAN ART: THE NEXT GENERATION / TOP 500 DES ARTISTES ACTUELS LES PLUS COTÉS - THE TOP-SELLING 500 ARTISTS WORLDWIDE CONTEMPORARY ART MARKET 2011/2012 LE RAPPORT ANNUEL ARTPRICE LE MARCHÉ DE L'ART CONTEMPORAIN THE ARTPRICE ANNUAL REPORT SOMMAIRE SUMMARY THE CONTEMPORARY ART MARKET 2011/2012 Foreword . page 9 THE LATEST TRENDS How well did Contemporary art sell this year? . page 11 Relative global market shares : Asia/Europe/USA . page 12 Competition between Beijing and Hong Kong . page 14 Europe offers both quantity and quality . page 15 Top 10 auction results in Europe . page 16 France: a counter-productive market . page 17 Paris - New York . page 19 Paris-London . .. page 20 Paris-Cannes . page 21 THE ART ELITE The year’s records: stepping up by the millions . page 25 China: a crowded elite . page 26 New records in painting: Top 3 . page 28 The Basquiat myth . page 28 Glenn Brown, art about art . page 29 Christopher Wool revolutionises abstract painting . page 30 New records in photography . page 31 Jeff Wall: genealogy of a record . page 32 Polemical works promoted as emblems . .. page 34 New records in sculpture & installation . page 36 Cady Noland: € 4 .2 m for Oozewald . page 36 Antony Gormley: new top price for Angel of the North at £ 3 4. m . .. page 36 Peter Norton’s records on 8 and 9 November 2011 . -

Behind the Thriving Scene of the Chinese Art Market -- a Research

Behind the thriving scene of the Chinese art market -- A research into major market trends at Chinese art market, 2006- 2011 Lifan Gong Student Nr. 360193 13 July 2012 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. F.R.R.Vermeylen Second reader: Dr. Marilena Vecco Master Thesis Cultural economics & Cultural entrepreneurship Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam 1 Abstract Since 2006, the Chinese art market has amazed the world with an unprecedented growth rate. Due to its recent emergence and disparity from the Western art market, it remains an indispensable yet unfamiliar subject for the art world. This study penetrates through the thriving scene of the Chinese art market, fills part of the gap by presenting an in-depth analysis of its market structure, and depicts the route of development during 2006-2011, the booming period of the Chinese art market. As one of the most important and largest emerging art markets, what are the key trends in the Chinese art market from 2006 to 2011? This question serves as the main research question that guides throughout the research. To answer this question, research at three levels is unfolded, with regards to the functioning of the Chinese art market, the geographical shift from west to east, and the market performance of contemporary Chinese art. As the most vibrant art category, Contemporary Chinese art is chosen as the focal art sector in the empirical part since its transaction cover both the Western and Eastern art market and it really took off at secondary art market since 2005, in line with the booming period of the Chinese art market. -

“The Era of Asia, the Art of Asia”

PRESS RELEASE | HONG KONG | 25 OCTOBER 2 0 1 3 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE ASIAN 20TH CENTURY AND CONTEMPORARY ART FALL AUCTIONS 2013 PRESENTING “THE ERA OF ASIA, THE ART OF ASIA” With highlights including the most complete collection of Zao Wou-Ki Rare Zeng Fanzhi triptych Hospital Triptych No.3 A series of classic paintings by Indo-European artists A special sale of Asian 20th Century and Contemporary works on paper |Asian 20th Century and Contemporary Art (Evening Sale), James Christie Room, November 23, Saturday, 7pm, Sale 3255| |Asian 20th Century Art (Day Sale), James Christie Room, November 24, Sunday, 10am, Sale 3256| |A Special Selection of Asian 20th Century & Contemporary Art (Day Sale), Woods Room, November 24, Sunday, 2:00pm, Sale 3259| |Asian Contemporary Art (Day Sale), James Christie Room, November 24, Sunday, 4:00pm, Sale 3257| Hong Kong - On November 23 and 24, Christie‘s Hong Kong will present 900 lots in four sales of Asian 20th Century & Contemporary Art during its Autumn 2013 season. Building on the success of the ―East Meets West‖ concept of the past two seasons, the upcoming Asian 20th Century & Contemporary Art sales are titled ―The Era of Asia, The Art of Asia.‖ They will showcase a broad range of distinctive works of art that illustrate the artistic blending of East and West, from works by Asian modernist masters to boundary-pushing creations from new contemporary talent. The Evening Sale will revolve around the theme of ―The Golden Era of Asian 20th Century and Contemporary Art‖ and will comprise a series of early works from the 1950s and 1960s by iconic modern painters, as well as a group of important pieces created by contemporary artists during the late 1980s and early 1990s. -

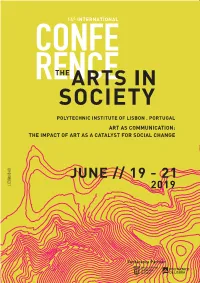

Art As Communication: Y the Impact of Art As a Catalyst for Social Change Cm

capa e contra capa.pdf 1 03/06/2019 10:57:34 POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE OF LISBON . PORTUGAL C M ART AS COMMUNICATION: Y THE IMPACT OF ART AS A CATALYST FOR SOCIAL CHANGE CM MY CY CMY K Fifteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society Against the Grain: Arts and the Crisis of Democracy NUI Galway Galway, Ireland 24–26 June 2020 Call for Papers We invite proposals for paper presentations, workshops/interactive sessions, posters/exhibits, colloquia, creative practice showcases, virtual posters, or virtual lightning talks. Returning Member Registration We are pleased to oer a Returning Member Registration Discount to delegates who have attended The Arts in Society Conference in the past. Returning research network members receive a discount o the full conference registration rate. ArtsInSociety.com/2020-Conference Conference Partner Fourteenth International Conference on The Arts in Society “Art as Communication: The Impact of Art as a Catalyst for Social Change” 19–21 June 2019 | Polytechnic Institute of Lisbon | Lisbon, Portugal www.artsinsociety.com www.facebook.com/ArtsInSociety @artsinsociety | #ICAIS19 Fourteenth International Conference on the Arts in Society www.artsinsociety.com First published in 2019 in Champaign, Illinois, USA by Common Ground Research Networks, NFP www.cgnetworks.org © 2019 Common Ground Research Networks All rights reserved. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review as permitted under the applicable copyright legislation, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process without written permission from the publisher. For permissions and other inquiries, please visit the CGScholar Knowledge Base (https://cgscholar.com/cg_support/en). -

William Gropper's

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas March – April 2014 Volume 3, Number 6 Artists Against Racism and the War, 1968 • Blacklisted: William Gropper • AIDS Activism and the Geldzahler Portfolio Zarina: Paper and Partition • Social Paper • Hieronymus Cock • Prix de Print • Directory 2014 • ≤100 • News New lithographs by Charles Arnoldi Jesse (2013). Five-color lithograph, 13 ¾ x 12 inches, edition of 20. see more new lithographs by Arnoldi at tamarind.unm.edu March – April 2014 In This Issue Volume 3, Number 6 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Fierce Barbarians Associate Publisher Miguel de Baca 4 Julie Bernatz The Geldzahler Portfoio as AIDS Activism Managing Editor John Murphy 10 Dana Johnson Blacklisted: William Gropper’s Capriccios Makeda Best 15 News Editor Twenty-Five Artists Against Racism Isabella Kendrick and the War, 1968 Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Shaurya Kumar 20 Zarina: Paper and Partition Online Columnist Jessica Cochran & Melissa Potter 25 Sarah Kirk Hanley Papermaking and Social Action Design Director Prix de Print, No. 4 26 Skip Langer Richard H. Axsom Annu Vertanen: Breathing Touch Editorial Associate Michael Ferut Treasures from the Vault 28 Rowan Bain Ester Hernandez, Sun Mad Reviews Britany Salsbury 30 Programs for the Théâtre de l’Oeuvre Kate McCrickard 33 Hieronymus Cock Aux Quatre Vents Alexandra Onuf 36 Hieronymus Cock: The Renaissance Reconceived Jill Bugajski 40 The Art of Influence: Asian Propaganda Sarah Andress 42 Nicola López: Big Eye Susan Tallman 43 Jane Hammond: Snapshot Odyssey On the Cover: Annu Vertanen, detail of Breathing Touch (2012–13), woodcut on Maru Rojas 44 multiple sheets of machine-made Kozo papers, Peter Blake: Found Art: Eggs Unique image. -

Asian Contemporary Art May 24-25

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 7, 2008 Contact: Kate Swan Malin +852 2978 9966 [email protected] Yvonne So +852 2978 9919 [email protected] Christie’s Hong Kong Presents Asian Contemporary Art May 24-25 • Largest and most-valuable sale of Asian Contemporary Art ever offered • Leading Names in Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Indian Contemporary Art highlight 2 days of sales • 417 works with a pre-sale estimate of HK$320 million/US$41million • Series kicks off with the inaugural Evening Sale of Asian Contemporary Art – a first for the category worldwide Asian Contemporary Art Sale Christie’s Hong Kong Evening Sale - Saturday, May 24, 7:30 p.m. Day Sale - Sunday, May 25, 1:30 p.m. Hong Kong – Christie’s, the world’s leading art business, will present a two-day series of sales devoted to Asian Contemporary Art on May 24 -25 in Hong Kong, opening with the first-ever Evening Sale for the category. This sale falls on the heels of Christie’s record-breaking sale of Asian Contemporary Art in November 2007* and will offer unrivalled examples from leading Contemporary Art masters from China, Japan, Korea, India and throughout Asia, including works from artists such as Zeng Fanzhi, Yue Minjun, Zhang Xiaogang, Wang Guangyi, Hong Kyoung Tack, Kim Tschang Yeul, Yoyoi Kusama, Aida Makoto, Yasuyuki Nishio, and Hisashi Tenmyouya. Offering 417 works across two important days of sales, this is the largest and most valuable offer of Asian Contemporary Art ever presented. Chinese Contemporary Art Chinese contemporary artists display a myriad range of styles. Yue Minjun’s work, with its vivid imagery and unique stylistic features, occupies a very special position in Contemporary Chinese art. -

Chinese Contemporary Art-7 Things You Should Know

Chinese Contemporary Art things you should know By Melissa Chiu Contents Introduction / 4 1 . Contemporary art in China began decades ago. / 14 2 . Chinese contemporary art is more diverse than you might think. / 34 3 . Museums and galleries have promoted Chinese contemporary art since the 1990s. / 44 4 . Government censorship has been an influence on Chinese artists, and sometimes still is. / 52 5 . The Chinese artists’ diaspora is returning to China. / 64 6 . Contemporary art museums in China are on the rise. / 74 7 . The world is collecting Chinese contemporary art. / 82 Conclusion / 90 Artist Biographies / 98 Further Reading / 110 Introduction 4 Sometimes it seems that scarcely a week goes by without a newspaper or magazine article on the Chinese contemporary art scene. Record-breaking auction prices make good headlines, but they also confer a value on the artworks that few of their makers would have dreamed possible when those works were originally created— sometimes only a few years ago, in other cases a few decades. It is easy to understand the artists’ surprise at their flourishing market and media success: the secondary auction market for Chinese contemporary art emerged only recently, in 2005, when for the first time Christie’s held a designated Asian Contemporary Art sale in its annual Asian art auctions in Hong Kong. The auctions were a success, including the modern and contemporary sales, which brought in $18 million of the $90 million total; auction benchmarks were set for contemporary artists Zhang Huan, Yan Pei-Ming, Yue Minjun, and many others. The following year, Sotheby’s held its first dedicated Asian Contemporary sale in New York. -

Trauma in Contemporary Chinese Art A

California College of the Arts Some Things Last a Long Time: Trauma in Contemporary Chinese Art A Thesis Submitted to The Visual Studies Faculty in Candidacy for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts in Visual Studies By Tingting Dai May 04, 2018 Abstract This essay examines how three Chinese artists, Liu Xiaodong, Yue Minjun and Ai Weiwei, approach the representation of trauma. I locate the effects of trauma in the way the artists manipulate the materials and subject matters and argue that the process results in a narrative sense of trauma. I contextualize their representation of trauma according to themes such as medium, historical references, and audience. I use trauma theory to address how artworks produce memory and response through symbolic subject matters. I end the thesis with a discussion about the U.S. reception of Chinese art that expresses trauma, focusing on the 2018 Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum exhibition “Art and China After 1989: Theater of the world.” Here, I argue… 2 Contemporary Chinese artists live with the physical and psychological trauma of the Cultural Revolution and the Tiananmen Square massacre, and they reenact memories of trauma through art in different ways. The Cultural Revolution started in the 1960s and was a national movement against any form of Western-influenced capitalism. Education was arguably one of the most affected aspects during this chaos, there was no university education for a decade, and later, as young artists participated in society as adults, their faith in the government was further crushed by the Tiananmen Square massacre in 1989. Artistic freedom was highly restricted by authorities after this event and the Cultural Revolution, and artists responded in different ways. -

A-Maze-Ing Laughter

YUE MINJUN A-maze-ing Laughter PUBLIC ART vancouver paintings capture the symptoms of the socialist culture of his time. The laughter is marked by eyes tightly shut, teeth bared, mouth out of proportion and wide open. The exaggera - tion is applied uniformly on all the figures depicted. Enigmatic as it seems, the laughter is interpreted by many as an indi - cation of state politics acting on everyday life and therefore suggesting a kind of mentality under tight social control. The laughing figures have become one of the most rec - ognizable representations in Chinese contemporary art. In recent years, the popularity of the laughing face has extended into popular culture. Commercial replicas of the figures in different sizes and media have become “must-haves” for many who wish to be in sync with contemporary China. The laughing figures have been growing in meaning over About the Work time. In the global context, the laughter has acquired a uni - versal appeal since it has been showing and interacting with A-maze-ing Laughter features the wide open-mouthed laughter many different cultures. It is perceived as inviting playfulness that is the signature trademark of Yue Minjun, one of the and joy as well as provoking thoughts about social conditions. most prominent contemporary Chinese artists known today. The artist often states that politics is rooted deeply in the The sculpture erected in Morton Park consists of fourteen cultural psyche and human nature, and therefore it is more bronze laughing figures. The happy faces are stylized carica - meaningful for art to tackle the deeper roots that shape the tures of the artist himself.