ETHJ Vol-18 No-1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legacy of the Pacific War: 75 Years Later August 2020

LEGACY OF THE PACIFIC WAR: 75 YEARS LATER August 2020 World War II in the Pacific and the Impact on the U.S. Navy By Rear Admiral Samuel J. Cox, U.S. Navy (Retired) uring World War II, the U.S. Navy fought the Pacific. World War II also saw significant social in every ocean of the world, but it was change within the U.S. Navy that carried forward the war in the Pacific against the Empire into the Navy of today. of Japan that would have the greatest impact on As it was at the end of World War II, the premier Dshaping the future of the U.S. Navy. The impact was type of ship in the U.S. Navy today is the aircraft so profound, that in many ways the U.S. Navy of carrier, protected by cruiser and destroyer escorts, today has more in common with the Navy in 1945 with the primary weapon system being the aircraft than the Navy at the end of World War II had with embarked on the carrier. (Command of the sea first the Navy in December 1941. With the exception and foremost requires command of the air over the of strategic ballistic missile submarines, virtually Asia sea, otherwise ships are very vulnerable to aircraft, every type of ship and command organization today Program as they were during World War II.) The carriers and is descended from those that were invented or escorts of today are bigger, more technologically matured in the crucible of World War II combat in sophisticated, and more capable than those of World Asia Program War II, although there are fewer of them. -

Texans Have Always Contributed a Surplus of Soldiers and Resources to the Nation’S Military

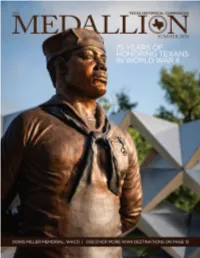

ISSN 0890-7595 Vol. 58, No. III thc.texas.gov [email protected] TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION John L. Nau, III Chair John W. Crain Vice Chair Gilbert E. “Pete” Peterson Secretary Earl Broussard, Jr. David A. Gravelle James “Jim” Bruseth Chief Justice Wallace B. Jefferson (ret.) Monica P. Burdette Laurie E. Limbacher Garrett Kieran Donnelly Catherine McKnight Renee Rupa Dutia Tom Perini Lilia Marisa Garcia Daisy Sloan White Mark Wolfe Executive Director Medallion STAFF Chris Florance Division Director Andy Rhodes Managing Editor Judy Jensen Sr. Graphic Design Coordinator TEXAS HISTORICAL thc.texas.gov Real places telling the real stories of Texas COMMISSION texastimetravel.com The Texas Heritage Trails LEADERSHIP LETTER Program’s travel resource texashistoricsites.com The THC’s 32 state historic properties thcfriends.org Friends of the Texas Historical Commission As veterans of the armed services, we’re honored to Learn about him at the modernized Nimitz Our Mission introduce The Medallion magazine issue commemo- Museum, part of the THC’s National Museum To protect and preserve the state’s historic and prehistoric of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, his hometown. resources for the use, education, enjoyment, and economic rating the roles played by Texas and Texans in World benefit of present and future generations. War II on the 75th anniversary of the end of the The Eisenhower Birthplace State Historic Site in global conflict. The Medallion is published quarterly by the Texas Historical Denison offers visitors background on General Commission. Address correspondence to: Managing Editor, The Medallion, P.O. Box 12276, Austin, TX 78711-2276. Portions While the war was horrific in every sense, the Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in of the newsletter that are not copyrighted or reprinted from other following articles help us understand the sacrifices Europe and future President of the United States. -

History of the German Element in Texas from 1820-1850, And

PD Commons PD Books PD Commons MORITZ TILING HISTORY OF The German Element in Texas FROM 1820- 1850 AND HISTORICAL SKETCHES OF THE GERMAN TEXAS SINGERS' LEAGUE AND HOUSTON TURNVEREIN FROM 1853-1913 BY MORITZ TILING Instructor in History, Houston Academy FIRST EDITION Published by Moritz Thing, Houston, Texas Nineteen Hundred and Thirteen PD Books PD Commons COPYRIGHT BY M. TILING 1913 PREFACE. This plain, unpretending monograph has been written for the purpose of preserving to posterity the records of German achievements in the colonization and upbuilding of the great state of Texas. The pioneer's humble life and courageous struggles are very often left unnoticed by the historian, yet, v/ithout his brave and patient labors none of the great commonwealths of the United States would exist. The early pioneer, whose brawny arm wielded the axe, who cleared the forest and broke the virgin soil, is as much a maker of a country, as the statesman, the diplom- atist and the soldier of today. His faithful work and often hazardous task are well worth remembering. The different Texas histories used in the public schools unfortunately are lamentably deficient with respect to the important part the Germans have taken in the coloniza- tion and shaping of Texas. Some of them, which are used extensively in the schools of the State, do not make any mention at all of the German immigration and its bearing on the rapid development— of Texas, while others at least state briefly that "Texas is indebted to her German till- ers of the soil for developments of great value, and which to Americans had been considered of impossible produc- tion in this climate." (Brown's School History of Texas, p. -

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress

Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Updated October 29, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS22478 Navy Ship Names: Background for Congress Summary Names for Navy ships traditionally have been chosen and announced by the Secretary of the Navy, under the direction of the President and in accordance with rules prescribed by Congress. Rules for giving certain types of names to certain types of Navy ships have evolved over time. There have been exceptions to the Navy’s ship-naming rules, particularly for the purpose of naming a ship for a person when the rule for that type of ship would have called for it to be named for something else. Some observers have perceived a breakdown in, or corruption of, the rules for naming Navy ships. Section 1749 of the FY2020 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) (S. 1790/P.L. 116-92 of December 20, 2019) prohibits the Secretary of Defense, in naming a new ship (or other asset) or renaming an existing ship (or other asset), from giving the asset a name that refers to, or includes a term referring to, the Confederate States of America, including any name referring to a person who served or held leadership within the Confederacy, or a Confederate battlefield victory. The provision also states that “nothing in this section may be construed as requiring a Secretary concerned to initiate a review of previously named assets.” Section 1749 of the House-reported FY2021 NDAA (H.R. 6395) would prohibit the public display of the Confederate battle flag on Department of Defense (DOD) property, including naval vessels. -

Naval Sonnel

LJREAU OF NAVAL SONNEL INFORMATION BULLETIN AUGUST 1942 NUMBER 305 We never do anything well till we cease to think about thc manner of doing it. KEEP 'EM SII~KLNGI An American Sub's Eye View of the Sinking of a Japanese Destroyer. This remarkable photograph, the first combat action photograph taken through the periscope of 8n American submarine, shows an enemy destroyer of one of the latest and largest types after it had been struck by two torpedoes launched by the submarine from which the picture was taken. The destroyer sank in nine minutes. Note the Rising Sun insignia on top of the turret to theleft, which serves as an identification mark for aircraft. Also note the two men in white scrambling over the conning-tower to the right. The marks on the left and the center line are etchings on the periscope. WORDSONCE SPOKEN CAN NEVER BE RECALLED 2 LET’S GET REALLY MAD AND STAY MAD ‘We quote from Jan Henrik Marsman’s article, “I escaped from Hong Kong”, published in the Saturday Evening Post dated June 6, 1942: “I saw the Japanese wantonly torture and finally murder British Officers and soldiers in Hong Kong. I saw them jab helpless civilian prisoners with bayonets. I witnessed the rape of English women by the soldiery. I saw the Japanese slowly starve English and American babies and I still wake up in the middle of the night hearing the feeble wails of these infant victims. I saw Hiro Hito’s savages outdo one another in.practicing assorted cruelties on captured English, Canadian, Indian and Chinese soldiers”. -

Texas Seaport Museum

i FOUNDED1960 . QUARTEIRLY VOE XXXIII. NO. I CONTENTS A Cygnet's Cry........................................................................................................................... 1 Texas Seaport Museum ........................................................................................................... 2 To Helen..................................................................................................................................... 3 Happy Hunting Ground 1992 (Queries) ............................................................................... 4 Welcome to Judy Duer............................................................................................................. 5 From The Family History Center........................................................................................... 6 Meeting Notice, Genealogy SIG.............................................................................................. 7 Book Reviews............................................................................................................................. 8 BASTROP COUNTY (TEXAS) MARRIAGE RECORDS........................................... 8 Beethoven Maennerchor seeks descendants....................................................................... 9 An English Family Through Eight Centuries: THE WARNEFORDS....................... 10 STS. PETER AND PAUL CATHOLIC CHURCH (Frelsburg, TX) RECORDS...... 16 PERiodical Source Index 1847-1885 [PERSI] .............................................................. -

Summer 2012 College of Liberal Arts Summer 2012 Contents

Summer 2012 College of liberal arts Summer 2012 contentS s > In PraISe of Play acwilliam M y LL e k Philosophy is a serious business — Alumni from diverse professions repeatedly seemingly abstruse and humorless. Yet tell me that, above all, the liberal arts chal- much philosophical thinking has been lenged them to think. Critical thinking can be THE born of humor and the creative power of acquired, of course, without the study of the play. Democritus, arguably the first liberal arts, but it’s the questions that the lib- philosopher of science, was known for his eral arts ask, rather than the thinking itself, propensity for laughter, and his serious that have special significance. Only in the lib- Democritus sense of play resulted in some remarkable eral arts are questions raised about the mean- JAMes A. PArente, Jr. INCREDIBLE Dean, College of Liberal Arts discoveries. ing of life, the nature of social, political, and economic order, and the variety of the human POWER OF LiBERAL ARTS In that vein we introduce this summer’s Reach with a jocular experience and our beliefs. cover as an entrée into the creativity of our faculty, students, and alumni. It is by virtue of their diversity that the liberal arts can provide a context for discerning connections between seemingly distinct Current public discussion about higher education has lost spheres of knowledge. The liberal arts have thrived for centu- THinKERS sight of the “serious play” of discovery and innovation tradi- ries because of their capacity to entertain fundamental questions tionally stimulated by universities. In the course of this year’s that elude definitive response, to force connections between did you know they fuel discovery intense presidential campaign, higher education itself has disparate fields, and to train generations of students to use both become, not only a topic, but also a target for divisive debate. -

99 NEWS P Ro File

Top spots in WACOA go to 99’s DECEMBER 1973 n w O S i w i u s THE NINETY-NINES, INC. • The Will Rogers World Airport International Headquarters International President Oklahoma City, Oklahoma 73159 Return Form 3579 to above address 2nd Class Postage pd. at North Little Rock. Ark. It was great to have sunshine on arrival at Philadel P u b lis h e r..........................................Lee Keenihan phia, meeting place for the Middle-East Section Octo Managing Editor..............................Mardo Crane ber 26-27, after a flight delayed by fog and airplane Assistant Editor .................................Betty Hicks switching. I had the pleasure of flying with Jerry Art Director............................... Betty Hagerman Roberts (Gov. N.Y.-N.J. Section) from the International Production Manager..................... Ron Oberlag airport to the Noarth PHL airport and the scenic tour Circulation Manager Loretta Gragg included a good look at the Philadelphia Navy Yard as well as her family-owned lumber yard. I also learned Contributing Editors .......................... Mary Foley that the big gas storage tanks (with the extra steel Virginia Thompson structure on the outside) are expandable with the need Director of Advertising ................ Maggie Wirth for capacity. Much hangar talk went on during the informal Halloween party that evening and some of the cos Contents tumes were on an early aviation theme, others the Cover Story — Betty Hicks ............................... 1 latest in stewardess dress. Disguises gave us many Susie Sewell Around The W orld In Fourteen surprises and laughter. Fay Wells (charter 99) arrived Days — by Joyce Failing ..............................2 late, straight from President Nixon’s press conference, and played tapes since Kay Brick H onored................................................5 most of us had missed it on television. -

One Hundred Thirteenth Congress of the United States of America

H. R. 4199 One Hundred Thirteenth Congress of the United States of America AT THE SECOND SESSION Begun and held at the City of Washington on Friday, the third day of January, two thousand and fourteen An Act To name the Department of Veterans Affairs medical center in Waco, Texas, as the ‘‘Doris Miller Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center’’. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, SECTION 1. FINDINGS. Congress makes the following findings: (1) On October 12, 1919, Doris Miller was born in Waco, Texas. (2) On September 16, 1939, Miller enlisted in the United States Navy as mess attendant, third class at Naval Recruiting Station, Dallas, Texas, to serve for a period of six years. (3) On February 16, 1941, Miller received a change of rating to mess attendant, second class. (4) On June 1, 1942, Miller received a change of rating to mess attendant, first class. (5) On June 1, 1943, Miller received a change of rating, to cook, third class. (6) On November 25, 1944, Miller was presumed dead by the Secretary of the Navy a year and a day after being carried as missing in action since November 24, 1943, while serving aboard USS Liscome Bay when that vessel was torpedoed and sunk in the Pacific Ocean. (7) Miller was awarded the Navy Cross Medal, Purple Heart Medal, American Defense Service Medal, Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal, and World War II Victory Medal. (8) Miller’s citation for the Navy Cross said ‘‘for distin- guished devotion to duty, extraordinary courage and disregard for his own personal safety during the attack on the Fleet in Pearl Harbor, Territory of Hawaii, by Japanese forces on December 7, 1941. -

Johann Christoph Friedrich Von Schiller

A Monument to Freedom, a Monument to All: Restoring the Johann Christoph Friedrich von Schiller Memorial in Como Park Spring 2013 Volume 48, Number 1 Colin Nelson-Dusek —Page 11 Rooted in Community One History of Service: The Guild of Catholic Women and Guild Incorporated Hayla Drake Page 3 Internationally known artist Jason Najarak’s “Ladder of Hope” mural, the centerpiece of Guild Incorporated’s donor wall, was inspired by others whose “genius and mental illness played out in many ways.” Najarak gifted the organization with his painting. Photo courtesy of Guild Incorporated. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY RAMSEY COUNTY President Chad Roberts Founding Editor (1964–2006) Virginia Brainard Kunz Editor Hıstory John M. Lindley Volume 48, Number 1 Spring 2013 RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE MISSION STATEMENT OF THE RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF DIRECTORS ON DECEMBER 20, 2007: Paul A. Verret Chair The Ramsey County Historical Society inspires current and future generations Cheryl Dickson to learn from and value their history by engaging in a diverse program First Vice Chair of presenting, publishing and preserving. William Frels Second Vice Chair Julie Brady Secretary C O N T E N T S Carolyn J. Brusseau Treasurer 3 Rooted in Community Thomas H. Boyd Immediate Past Chair One History of Service: Anne Cowie, Joanne A. Englund, The Guild of Catholic Women and Guild Incorporated Thomas Fabel, Howard Guthmann, Hayla Drake Douglas Heidenreich, Richard B. Heydinger, Jr., John Holman, Kenneth H. Johnson, Elizabeth M. Kiernat, David Kristal, 11 A Monument to Freedom, a Monument to All: Carl Kuhrmeyer, Father Kevin M. -

The Sinking of USS Liscome Bay Posted in HISTORY up CLOSE on November 24, 2014

The Sinking of USS Liscome Bay posted in HISTORY UP CLOSE on November 24, 2014 View of the escort carrier Liscome Bay (CVE 56) underway just over two months before she was sunk by a Japanese submarine. In 1943, a young officer reporting aboard his first command, an escort carrier under construction in Tacoma, Washington, noted a homemade sign affixed to a bulkhead by some sailor as an attempt at macabre humor. It read “Torpedo Junction” in recognition of the belief that the World War II escort carriers, built quickly on merchant ship hulls, were susceptible to enemy torpedoes because they lacked the armor of their larger deck counterparts. Of the 77 escort carriers commissioned during World War II, a total of 6 were lost to enemy action, which speaks volumes about their durability given that they dodged kamikazes while supporting beachheads,, fought against overwhelming odds at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, and hunted German U-Boats in the Atlantic. For one of them, Liscome Bay (CVE 56), the “Torpedo Junction” sign would prove no joke, but a grim reality. Named after a body of water in Alaska, Liscome Bay began her path to Pacific combat with her keel laying on December 9, 1942, at the Kaiser Shipbuilding Company Yard in Vancouver, Washington. Commissioned on August 7, 1943, the escort carrier and her crew had little time to get their sea legs, in October steaming for Hawaii to join the forces assembling for Operation Galvanic, the invasion of the Gilbert Islands. With an overall length of 512 feet and a displacement of 7,800 tons, Liscome Bay and the other escort carriers that were part of the naval forces supporting the operation were assigned to provide the vital close air support for the Marines and Army troops storming ashore. -

2020 Summer the Medallion

ISSN 0890-7595 Vol. 58, No. III thc.texas.gov [email protected] TEXAS HISTORICAL COMMISSION John L. Nau, III Chair John W. Crain Vice Chair Gilbert E. “Pete” Peterson Secretary Earl Broussard, Jr. David A. Gravelle James “Jim” Bruseth Chief Justice Wallace B. Jefferson (ret.) Monica P. Burdette Laurie E. Limbacher Garrett Kieran Donnelly Catherine McKnight Renee Rupa Dutia Tom Perini Lilia Marisa Garcia Daisy Sloan White Mark Wolfe Executive Director Medallion STAFF Chris Florance Division Director Andy Rhodes Managing Editor Judy Jensen Sr. Graphic Design Coordinator TEXAS HISTORICAL thc.texas.gov Real places telling the real stories of Texas COMMISSION texastimetravel.com The Texas Heritage Trails LEADERSHIP LETTER Program’s travel resource texashistoricsites.com The THC’s 32 state historic properties thcfriends.org Friends of the Texas Historical Commission As veterans of the armed services, we’re honored to Learn about him at the modernized Nimitz Our Mission introduce The Medallion magazine issue commemo- Museum, part of the THC’s National Museum To protect and preserve the state’s historic and prehistoric of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg, his hometown. resources for the use, education, enjoyment, and economic rating the roles played by Texas and Texans in World benefit of present and future generations. War II on the 75th anniversary of the end of the The Eisenhower Birthplace State Historic Site in global conflict. The Medallion is published quarterly by the Texas Historical Denison offers visitors background on General Commission. Address correspondence to: Managing Editor, The Medallion, P.O. Box 12276, Austin, TX 78711-2276. Portions While the war was horrific in every sense, the Dwight Eisenhower, Supreme Allied Commander in of the newsletter that are not copyrighted or reprinted from other following articles help us understand the sacrifices Europe and future President of the United States.