BRITISH Policies for the American West, Especially the Procla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vandalia: the First West Virginia?

Vandalia: The First West Virginia? By James Donald Anderson Volume 40, No. 4 (Summer 1979), pp. 375-92 In 1863, led by a group of staunch Unionists, the western counties of Virginia seceded from their mother commonwealth to form a new state. This was not the first attempt to separate the mountanious area from the piedmont and the tidewater country. Patriotism, however, played little part that time. Less than a century previous a group of entrepreneurs and land speculators from the eastern seaboard and England had endeavored to establish a new colony, Vandalia, in the frontier region south and east of the Ohio River. The boundaries of the proposed province closely match those of the present state of West Virginia. Their efforts ended in failure, but that was not for a lack of trying. Since the country was sparsely populated, the inspiration for separation had to come from elsewhere. Some of the leading merchants and politicians in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and England hoped to profit from their efforts. Printer and philosopher Benjamin Franklin, his son Sir William, governor of New Jersey, Superintendent of Indian Affairs in the Northern Department Sir William Johnson, his deputy George Croghan, merchants George Morgan and John Baynton, and lawyer and Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly Joseph Galloway all interested themselves in the project. The leading lights of the movement, though, were members of a prominent and prosperous Quaker mercantile family, the Whartons of Philadelphia.1 The Wharton males, guided and inspired by patriarch Joseph, Senior (1707-76), had risen in two generations from relative poverty to riches in local trade, the export-import business, and sponsoring small industries. -

PEAES Guide: the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

PEAES Guide: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/hsp.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-732-6200 http://www.hsp.org Overview: The entries in this survey highlight some of the most important collections, as well as some of the smaller gems, that researchers will find valuable in their work on the early American economy. Together, they are a representative sampling of the range of manuscript collections at HSP, but scholars are urged to pursue fruitful lines of inquiry to locate and use the scores of additional materials in each area that is surveyed here. There are numerous helpful unprinted guides at HSP that index or describe large collections. Some of these are listed below, especially when they point in numerous directions for research. In addition, the HSP has a printed Guide to the Manuscript Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP: Philadelphia, 1991), which includes an index of proper names; it is not especially helpful for searching specific topics, item names, of subject areas. In addition, entries in the Guide are frequently too brief to explain the richness of many collections. Finally, although the on-line guide to the manuscript collections is generally a reproduction of the Guide, it is at present being updated, corrected, and expanded. This survey does not contain a separate section on land acquisition, surveying, usage, conveyance, or disputes, but there is much information about these subjects in the individual collections reviewed below. -

The Wharton-Fitler House

The Wharton-Fitler House A history of 407 Bank Avenue, Riverton, New Jersey Prepared by Roger T. Prichard for the Historical Society of Riverton, rev. November 30, 2019 © Historical Society of Riverton 407 Bank Avenue in 2019 photo by Roger Prichard This house is one of the ten riverbank villas which the founders of Riverton commissioned from architect Samuel Sloan, built during the spring and summer of 1851, the first year of Riverton’s existence. It looks quite different today than when built, due to an expansion in the 1880s. Two early owners, Rodman Wharton and Edwin Fitler, Jr., were from families of great influence in many parts of American life. Each had a relative who was a mayor of the City of Philadelphia. Page 1 of 76 The first owner of this villa was Philadelphian Rodman Wharton, the youngest of those town founders at age 31 and, tragically, the first to die. Rodman Wharton was the scion of several notable Philadelphia Quaker families with histories in America dating to the 1600s. Tragically, Rodman Wharton’s life here was brief. He died in this house at the age of 34 on July 20, 1854, a victim of the cholera epidemic which swept Philadelphia that summer. After his death, the house changed hands several times until it was purchased in 1882 by Edwin, Jr. and Nannie Fitler. Edwin was the son of Philadelphia’s popular mayor of the same name who managed the family’s successful rope and cordage works in Bridesburg. The Fitlers immediately enlarged and modernized the house, transforming its simpler 1851 Quaker appearance to a fashionable style today known as Queen Anne. -

Free to Speculate

ECONOMICHISTORY Free to Speculate BY KARL RHODES s Britain’s secretary of state land grants, so he reasoned that a much British frontier for the Colonies, Wills Hill, bigger proposal would have a much policy threatened Athe Earl of Hillsborough, vehe- smaller chance of winning approval. mently opposed American settlement But Franklin and his partners turned Colonial land west of the Appalachian Mountains. As Hillsborough’s tactic against him. They the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly’s increased their request to 20 million speculation agent in London, Benjamin Franklin acres only after expanding their partner- on the eve of enthusiastically advocated trans-Appa- ship to include well-connected British lachian expansion. The two bitter ene- bankers and aristocrats, many of them the American mies disagreed about many things, and Hillsborough’s enemies. This Anglo- British land policy in the Colonies was American alliance proposed a new colo- Revolution at or near the top of the list. ny called Vandalia, a name that Franklin In the late 1760s, Franklin joined recommended to honor the queen’s pur- forces with Colonial land speculators ported Vandal ancestry. The new colony who were asking King George’s Privy would have included nearly all of what Council to validate their claim on more is now West Virginia, most of eastern than 2 million acres along the Ohio Kentucky, and a portion of southwest River. It was a large western land grab — Virginia, according to a map in Voyagers even by Colonial American standards to the West by Harvard historian Bernard — and the speculators fully expected Bailyn. Hillsborough to object. -

John Dickinson Papers Dickinson Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared by Holly Mengel

John Dickinson papers Dickinson Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel.. Last updated on September 02, 2020. Library Company of Philadelphia 2010.09.30 John Dickinson papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials......................................................................................................................................... 10 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 13 Series I. John Dickinson........................................................................................................................13 Series II. Mary Norris Dickinson..........................................................................................................33 -

H. Doc. 108-222

34 Biographical Directory DELEGATES IN THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS CONNECTICUT Dates of Attendance Andrew Adams............................ 1778 Benjamin Huntington................ 1780, Joseph Spencer ........................... 1779 Joseph P. Cooke ............... 1784–1785, 1782–1783, 1788 Jonathan Sturges........................ 1786 1787–1788 Samuel Huntington ................... 1776, James Wadsworth....................... 1784 Silas Deane ....................... 1774–1776 1778–1781, 1783 Jeremiah Wadsworth.................. 1788 Eliphalet Dyer.................. 1774–1779, William S. Johnson........... 1785–1787 William Williams .............. 1776–1777 1782–1783 Richard Law............ 1777, 1781–1782 Oliver Wolcott .................. 1776–1778, Pierpont Edwards ....................... 1788 Stephen M. Mitchell ......... 1785–1788 1780–1783 Oliver Ellsworth................ 1778–1783 Jesse Root.......................... 1778–1782 Titus Hosmer .............................. 1778 Roger Sherman ....... 1774–1781, 1784 Delegates Who Did Not Attend and Dates of Election John Canfield .............................. 1786 William Hillhouse............. 1783, 1785 Joseph Trumbull......................... 1774 Charles C. Chandler................... 1784 William Pitkin............................. 1784 Erastus Wolcott ...... 1774, 1787, 1788 John Chester..................... 1787, 1788 Jedediah Strong...... 1782, 1783, 1784 James Hillhouse ............... 1786, 1788 John Treadwell ....... 1784, 1785, 1787 DELAWARE Dates of Attendance Gunning Bedford, -

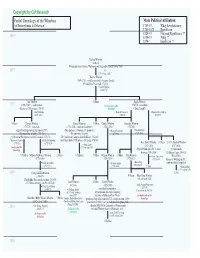

Wharton-PA-1

Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Whartons Main Political Affiliation: (of Pennsylvania & Delaware) 1763-83 Whig Revolutionary 1789-1823 Republican 1824-33 National Republican ?? 1600 1834-53 Whig ?? 1854- Republican ?? Richard Wharton (1646-83) (Emigrated from Overton, Westmoreland, England to Pennsylvania, 1683) 1650 = ???? (????-at least 1683) Thomas Wharton (1664-1718); (wealthy merchant); (became Quaker) (Philadelphia PA council, 1713-18) = Rachel Thomas (1664-1747) John Wharton 6 Others Joseph Wharton 1700 (1700-37/61?); (saddlemaker) See Carpenter of PA (1707-76); (merchant) (Chester co. PA coroner, 1730-37) Genealogy ("Duke Joseph") = Mary Dobbins Hannah Carpenter = = Hannah Owen (Ogden) (1696-1763) (1711-51) (1720-91) 4 Others Thomas Wharton Samuel Wharton 8 Others Charles Wharton Carpenter Wharton (1735-78); (merchant) (1732-1800); (merchant/landowner) (1742-1836) (1747-80) (signed Non-Importation Agreement, 1765) (PA legislature); (Vandalia Co. promoter) = Hannah Redwood = Elizabeth Davis (PA committee of safety, 1775-76) (PA committee of safety) (1759-96) (1751?-1816) (President PA supreme executive council, 1776-78) (US Continental Congress from Delaware, 1782-83) 1750Susannah Lloyd = = Elizabeth Fishbourne (Southwark district DE justice); (DE judge, 1790-91) (1739-72) (1752-1826) Gen. Robert Wharton 5 Others Lt. Col. Franklin Wharton = Sarah Lewis (1757-1834) (1767-1818) See Lloyd of PA (1732-at least 1762) Genealogy (Mayor Philadelphia PA 15 times (Commandante between 1798-1834) US Marine Corps, 1804-18) -

SAMUEL WHARTON and the INDIANS'rights to SELL THEIR LAND: an EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY VIEW James D

SAMUEL WHARTON AND THE INDIANS'RIGHTS TO SELL THEIR LAND: AN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY VIEW James D. Anderson founding and establishing of European colonies in North TheAmerica on a firmand lasting basis resulted from the occupation of lands loosely held by native Indian nations. The movement of white settlers inland from the seaboard necessarily occurred at the expense of the inhabitants possessing or at least using the land. The legality of such appropriations by whatever means — treaties, purchases, or simply "squatters' rights" — has been debated to this day. In pre- Revolutionary America, especially after 1763, the conflict between public and private interests inland ventures came to the fore. A major question involved the rights of Indians to relinquish areas under their control with or without the permission of the crown. Many colonials believed the tribes could voluntarily and legally sell their lands to individual Americans without approval of the British government. The immense amounts of undeveloped interior acreage attracted specu- lators who adhered to that viewpoint. The Whartons, 1 prominent Quaker merchants of Philadelphia, particularly Samuel, became lead- ing advocates for, and defenders of, the Indians' rights to dispose of their property as they saw fitupon their own authority. The patriarch of the family, Joseph (1707-1776), often referred to as "the Grand Duke," acted mainly as an investor in various land deals, particularly inand around his native city. His sons, however, provided leadership as well as financial backing to several endeavors, including involvement in such cooperative efforts as the Illinois Company, the Indiana Company, and the Grand Ohio or Vandalia Born in Columbus, Ohio, Dr. -

I a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts And

“ALL THE NATIONS TO THE SUN SETTING” GEORGE CROGHAN, EXTENDING THE LIMITS OF EMPIRE IN BRITISH NORTH AMERICA A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Liberal Studies By Jeffrey Michael Zimmerman, M.B.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. December 28, 2015 i ©2015 by Jeffrey Michael Zimmerman All Rights Reserved ii “ALL THE NATIONS TO THE SUN SETTING” GEORGE CROGHAN, EXTENDING THE LIMITS OF EMPIRE IN BRITISH NORTH AMERICA Jeffrey Michael Zimmerman, MBA Chair: Ronald M. Johnson, PhD ABSTRACT George Croghan was a mid-eighteenth-century British Indian agent. Born in Ireland, he came to America and settled in Pennsylvania in 1741. As an Ohio Valley fur trader he pushed far enough west to invite destruction of his Great Miami River depot by New France in 1752. Over time he befriended Shawnee, Ohio Huron and Miami Indians. Indian Department Superintendent Sir William Johnson rewarded his countryman’s effectiveness by appointing him western deputy. Britain’s victory in the French and Indian War added Illinois to Croghan’s responsibilities. General Lord Jeffrey Amherst led Britain’s war efforts; he was replaced by General Thomas Gage, under whom Croghan had served at Braddock’s Defeat. Pontiac’s War ensued; Gage and Johnson relied on Croghan, who knew the Ottawa leader, to end it. However, Croghan’s focus became blurred by land speculation. Several western land schemes crafted by Croghan and Philadelphia financier Samuel Wharton either failed or were cut short by the American Revolution. -

The Proposed Colony of Vandalia

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 http://archive.org/details/proposedcolonyofOOhull THE PROPOSED COLONY OF VANDALIA BY ANNA LEO HULL A. B. University of Illinois, 1910 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN HISTORY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL j2? OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1914 H«7 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL May 27 19&4 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Anna Leo Hull ENTITLED The Proposed Colony of Vandalia BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts in History ^^^^^^^ ^ j n Charge of Major Work Head of Department Recommendation concurred in: Committee on Final Examination 284588 4" UIUC CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Conspiracy of Pontiac- -Organization of Land Companies — Procla- mation of 1763- -Indian Boundary Line. CHAPTER I BEGINNING OF THE WALPOLE COMPANY 7 Grants in the Ohio Valley—Organization of the Walpole Company --Petition for Land- -Boundary of Vandalia--Action of the Treas ury Board. CHAPTER II ACTION CP THE LORD COMMISSIONERS FOR TRADE AND PLANTATION 14 Complications with Virginia—Report of the Board of Trade, April 15, 1772—Report of the Committee of Council for Plan- tation Affairs, July 1, 1772—Resignation of Hillsborough— Government of Vandal ia. CHAPTER III ACTION OF THE ATTORNEY AND SOLICITOR GENERAL, AND THE CONGRESS OF THE UNITED STATES 29 Objections of the Attorney and Solicitor General- -Pamphlets Published— Second Order to the Attorney and Solicitor Gen- eral- -Dunmore Activities— V/alpole Renews Pet it ion--William Trent, Agent in America- -Act ion of Congress. -

The Plight and the Bounty: Squatters, War Profiteers, and the Transforming Hand of Sovereignty in Indian Country, 1750-1774

The Plight and the Bounty: Squatters, War Profiteers, and the Transforming Hand of Sovereignty in Indian Country, 1750-1774 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Melissah J. Pawlikowski Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. John L. Brooke, Advisor Dr. Lucy Murphy Dr. Margaret Newell Copyright by Melissah J. Pawlikowski 2014 Abstract “The Plight and the Bounty: Squatters, War Profiteers & the Transforming Hand of Sovereignty in the Indian Country, 1750-1774” explores the creation of a European & Indian commons in the Ohio Valley as well as an in-depth examination of the network of interethnic communities and a secondary economic system created by refugee Euroamerican, Black, and Indian inhabitants. Six elements of creolization—the fusion of language, symbols, and legal codes; the adoption of material goods; and the exchange of labor and knowledge—resulted in ethnogenesis and a local culture marked by inclusivity, tolerance, and a period of peace. Finally this project details how, in the absence of traditional power brokers, Indians and Europeans created and exchanged geopolitical power between local Indians and Euroamericans as a method of legitimizing authority for their occupation of the Ohio Valley. ii Vita 2005 ............................................................... B.A., History, University of Pittsburgh 2007 .............................................................. -

National Identity, Loyalty, and Backcountry Merchants in Revolutionary America, 1740-1816

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-1-2015 Trading Identities: National Identity, Loyalty, and Backcountry Merchants in Revolutionary America, 1740-1816 Timothy Charles Hemmis University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hemmis, Timothy Charles, "Trading Identities: National Identity, Loyalty, and Backcountry Merchants in Revolutionary America, 1740-1816" (2015). Dissertations. 77. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/77 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi TRADING IDENTITIES: NATIONAL IDENTITY, LOYALTY, AND BACKCOUNTRY MERCHANTS IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1740-1816 by Timothy Charles Hemmis Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2015 ABSTRACT TRADING IDENTITIES: NATIONAL IDENTITY, LOYALTY, AND BACKCOUNTRY MERCHANTS IN REVOLUTIONARY AMERICA, 1740-1816 by Timothy Charles Hemmis May 2015 This project tracks the lives a select group of Philadelphia frontier merchants such as George Morgan, David Franks, and others from 1754-1811. “Trading Identities” traces the trajectory of each man’s economic and political loyalties during the Revolutionary period. By focusing on the men of trading firms operating in Philadelphia, the borderlands and the wider world, it becomes abundantly clear that their identities were shaped and sustained by their commercial concerns—not by any new political ideology at work in this period.