Vandalia: the First West Virginia?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PEAES Guide: the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

PEAES Guide: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/hsp.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-732-6200 http://www.hsp.org Overview: The entries in this survey highlight some of the most important collections, as well as some of the smaller gems, that researchers will find valuable in their work on the early American economy. Together, they are a representative sampling of the range of manuscript collections at HSP, but scholars are urged to pursue fruitful lines of inquiry to locate and use the scores of additional materials in each area that is surveyed here. There are numerous helpful unprinted guides at HSP that index or describe large collections. Some of these are listed below, especially when they point in numerous directions for research. In addition, the HSP has a printed Guide to the Manuscript Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP: Philadelphia, 1991), which includes an index of proper names; it is not especially helpful for searching specific topics, item names, of subject areas. In addition, entries in the Guide are frequently too brief to explain the richness of many collections. Finally, although the on-line guide to the manuscript collections is generally a reproduction of the Guide, it is at present being updated, corrected, and expanded. This survey does not contain a separate section on land acquisition, surveying, usage, conveyance, or disputes, but there is much information about these subjects in the individual collections reviewed below. -

BRITISH Policies for the American West, Especially the Procla

The Impact of ^British Western Policy on the Coming of the c ^American RKevolution in Pennsylvania RITISH policies for the American West, especially the Procla- mation of 1763 and the Quebec Act of 1774, are usually B included among the causes of the American Revolution. The degree of alienation may be disputed, but most historians have accepted the proposition that Americans were almost ordained to resent any interference with western expansion. Thus, we are told that the Proclamation of 1763 "became a source of acute discon- tent"; that "countless Americans, especially land speculators, were dismayed and angered." Both individual settlers and land specu- lators "resented more or less keenly the restrictive policies of the home government," as they saw "the whole region on which men had fastened such high hopes . reserved to the despised Indians." It was "another example of the readiness of the British ministry to subordinate [American] interests to the interests of others." In short, one recent study concludes, "British western policy from the institution of the Proclamation of 1763 to the Quebec Act of 1774 was very unpopular."1 These generalizations, however, while they may apply to colonies such as Virginia, do not reflect the attitudes of Pennsylvanians. Though British western policies did affect the Pennsylvania frontier, and though Pennsylvanians did participate in Ohio Valley land 1 The author wishes to thank Richard A. Ryerson, Jack M. Sosin, Harry M. Ward and Nicholas B. Wainwright for their suggestions in the preparation of this article. Bernhard Knollenberg, Origin ofthe American Revolution (New York, 1961), 102; Thomas A. Bailey, The American Pagenty 4th ed. -

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution

POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CAMPAIGN 273 POINT PLEASANT 1774 Prelude to the American Revolution JOHN F WINKLER ILLUSTRATED BY PETER DENNIS Series editor Marcus Cowper © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 5 The strategic situation The Appalachian frontier The Ohio Indians Lord Dunmore’s Virginia CHRONOLOGY 17 OPPOSING COMMANDERS 20 Virginia commanders Indian commanders OPPOSING ARMIES 25 Virginian forces Indian forces Orders of battle OPPOSING PLANS 34 Virginian plans Indian plans THE CAMPAIGN AND BATTLE 38 From Baker’s trading post to Wakatomica From Wakatomica to Point Pleasant The battle of Point Pleasant From Point Pleasant to Fort Gower THE AFTERMATH 89 THE BATTLEFIELD TODAY 93 FURTHER READING 94 INDEX 95 © Osprey Publishing • www.ospreypublishing.com 4 British North America in1774 British North NEWFOUNDLAND Lake Superior Quebec QUEBEC ISLAND OF NOVA ST JOHN SCOTIA Montreal Fort Michilimackinac Lake St Lawrence River MASSACHUSETTS Huron Lake Lake Ontario NEW Michigan Fort Niagara HAMPSHIRE Fort Detroit Lake Erie NEW YORK Boston MASSACHUSETTS RHODE ISLAND PENNSYLVANIA New York CONNECTICUT Philadelphia Pittsburgh NEW JERSEY MARYLAND Point Pleasant DELAWARE N St Louis Ohio River VANDALIA KENTUCKY Williamsburg LOUISIANA VIRGINIA ATLANTIC OCEAN NORTH CAROLINA Forts Cities and towns SOUTH Mississippi River CAROLINA Battlefields GEORGIA Political boundary Proposed or disputed area boundary -

The Protocols of Indian Treaties As Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Departmental Papers (Religious Studies) Department of Religious Studies 9-2015 How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society Anthony F C Wallace University of Pennsylvania Timothy B. Powell University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Religion Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Wallace, Anthony F C and Powell, Timothy B., "How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society" (2015). Departmental Papers (Religious Studies). 15. https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers/15 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/rs_papers/15 For more information, please contact [email protected]. How to Buy a Continent: The Protocols of Indian Treaties as Developed by Benjamin Franklin and Other Members of the American Philosophical Society Abstract In 1743, when Benjamin Franklin announced the formation of an American Philosophical Society for the Promotion of Useful Knowledge, it was important for the citizens of Pennsylvania to know more about their American Indian neighbors. Beyond a slice of land around Philadelphia, three quarters of the province were still occupied by the Delaware and several other Indian tribes, loosely gathered under the wing of an Indian confederacy known as the Six Nations. Relations with the Six Nations and their allies were being peacefully conducted in a series of so-called “Indian Treaties” that dealt with the fur trade, threats of war with France, settlement of grievances, and the purchase of land. -

A History of Appalachia

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Appalachian Studies Arts and Humanities 2-28-2001 A History of Appalachia Richard B. Drake Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Drake, Richard B., "A History of Appalachia" (2001). Appalachian Studies. 23. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_appalachian_studies/23 R IC H ARD B . D RA K E A History of Appalachia A of History Appalachia RICHARD B. DRAKE THE UNIVERSITY PRESS OF KENTUCKY Publication of this volume was made possible in part by grants from the E.O. Robinson Mountain Fund and the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright © 2001 by The University Press of Kentucky Paperback edition 2003 Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kenhlcky Eastern Kentucky University, The Filson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com 12 11 10 09 08 8 7 6 5 4 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Drake, Richard B., 1925- A history of Appalachia / Richard B. -

The Wharton-Fitler House

The Wharton-Fitler House A history of 407 Bank Avenue, Riverton, New Jersey Prepared by Roger T. Prichard for the Historical Society of Riverton, rev. November 30, 2019 © Historical Society of Riverton 407 Bank Avenue in 2019 photo by Roger Prichard This house is one of the ten riverbank villas which the founders of Riverton commissioned from architect Samuel Sloan, built during the spring and summer of 1851, the first year of Riverton’s existence. It looks quite different today than when built, due to an expansion in the 1880s. Two early owners, Rodman Wharton and Edwin Fitler, Jr., were from families of great influence in many parts of American life. Each had a relative who was a mayor of the City of Philadelphia. Page 1 of 76 The first owner of this villa was Philadelphian Rodman Wharton, the youngest of those town founders at age 31 and, tragically, the first to die. Rodman Wharton was the scion of several notable Philadelphia Quaker families with histories in America dating to the 1600s. Tragically, Rodman Wharton’s life here was brief. He died in this house at the age of 34 on July 20, 1854, a victim of the cholera epidemic which swept Philadelphia that summer. After his death, the house changed hands several times until it was purchased in 1882 by Edwin, Jr. and Nannie Fitler. Edwin was the son of Philadelphia’s popular mayor of the same name who managed the family’s successful rope and cordage works in Bridesburg. The Fitlers immediately enlarged and modernized the house, transforming its simpler 1851 Quaker appearance to a fashionable style today known as Queen Anne. -

Free to Speculate

ECONOMICHISTORY Free to Speculate BY KARL RHODES s Britain’s secretary of state land grants, so he reasoned that a much British frontier for the Colonies, Wills Hill, bigger proposal would have a much policy threatened Athe Earl of Hillsborough, vehe- smaller chance of winning approval. mently opposed American settlement But Franklin and his partners turned Colonial land west of the Appalachian Mountains. As Hillsborough’s tactic against him. They the Pennsylvania Provincial Assembly’s increased their request to 20 million speculation agent in London, Benjamin Franklin acres only after expanding their partner- on the eve of enthusiastically advocated trans-Appa- ship to include well-connected British lachian expansion. The two bitter ene- bankers and aristocrats, many of them the American mies disagreed about many things, and Hillsborough’s enemies. This Anglo- British land policy in the Colonies was American alliance proposed a new colo- Revolution at or near the top of the list. ny called Vandalia, a name that Franklin In the late 1760s, Franklin joined recommended to honor the queen’s pur- forces with Colonial land speculators ported Vandal ancestry. The new colony who were asking King George’s Privy would have included nearly all of what Council to validate their claim on more is now West Virginia, most of eastern than 2 million acres along the Ohio Kentucky, and a portion of southwest River. It was a large western land grab — Virginia, according to a map in Voyagers even by Colonial American standards to the West by Harvard historian Bernard — and the speculators fully expected Bailyn. Hillsborough to object. -

A Reinterpretation of Dunmore's

A Reinterpretation of Dunmore’s War BY JAMES CORBETT DAVID (Editor’s Note: The Journal of Backcountry Studies announces the publication, by the University Press of Virginia, of a major biography of Lord Dunmore, the last Royal Governor of Virginia by Dr. James Corbett David. Dunmore’s most famous exploit was his invasion of Native lands in the Ohio Valley, July to October, 1774. His depiction of the peace settlement is a distillation of the entire book, and, with the generous permission of the publisher and author, we offer this excerpt as an announcement of this landmark study in Backcountry history. RMC) By the terms of the treaty of Camp Charlotte, the Shawnees acquiesced to the Ohio River boundary established without their consent at Fort Stanwix in 1768. From now on, they would have to hunt on the northwest side of the river. They were also ordered to return all prisoners and stolen property, including slaves and horses, and hand over several hostages of their own to ensure their compliance pending the negotiation of a permanent peace at Pittsburgh the following summer. If all of these terms were met, Dunmore was “willing to bury the Hatchet” and once again protect the Shawnees “as an Elder Brother.” He sought to discredit reports that the Delawares had caused the war through treachery, urging the Shawnees “to bury in oblivion these idle prejudices against your Grand Fathers the Delawares, & see each other on your former friendly terms.” With the Fort Stanwix cession evidently secured, Dunmore thus sought to restore the political relations that, he believed, best promoted peace and order, albeit on Virginia’s terms. -

John Dickinson Papers Dickinson Finding Aid Prepared by Finding Aid Prepared by Holly Mengel

John Dickinson papers Dickinson Finding aid prepared by Finding aid prepared by Holly Mengel.. Last updated on September 02, 2020. Library Company of Philadelphia 2010.09.30 John Dickinson papers Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Biography/History..........................................................................................................................................4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 6 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials......................................................................................................................................... 10 Controlled Access Headings........................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 13 Series I. John Dickinson........................................................................................................................13 Series II. Mary Norris Dickinson..........................................................................................................33 -

H. Doc. 108-222

34 Biographical Directory DELEGATES IN THE CONTINENTAL CONGRESS CONNECTICUT Dates of Attendance Andrew Adams............................ 1778 Benjamin Huntington................ 1780, Joseph Spencer ........................... 1779 Joseph P. Cooke ............... 1784–1785, 1782–1783, 1788 Jonathan Sturges........................ 1786 1787–1788 Samuel Huntington ................... 1776, James Wadsworth....................... 1784 Silas Deane ....................... 1774–1776 1778–1781, 1783 Jeremiah Wadsworth.................. 1788 Eliphalet Dyer.................. 1774–1779, William S. Johnson........... 1785–1787 William Williams .............. 1776–1777 1782–1783 Richard Law............ 1777, 1781–1782 Oliver Wolcott .................. 1776–1778, Pierpont Edwards ....................... 1788 Stephen M. Mitchell ......... 1785–1788 1780–1783 Oliver Ellsworth................ 1778–1783 Jesse Root.......................... 1778–1782 Titus Hosmer .............................. 1778 Roger Sherman ....... 1774–1781, 1784 Delegates Who Did Not Attend and Dates of Election John Canfield .............................. 1786 William Hillhouse............. 1783, 1785 Joseph Trumbull......................... 1774 Charles C. Chandler................... 1784 William Pitkin............................. 1784 Erastus Wolcott ...... 1774, 1787, 1788 John Chester..................... 1787, 1788 Jedediah Strong...... 1782, 1783, 1784 James Hillhouse ............... 1786, 1788 John Treadwell ....... 1784, 1785, 1787 DELAWARE Dates of Attendance Gunning Bedford, -

Wharton-PA-1

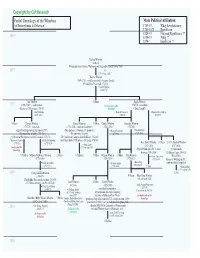

Copyright by CLP Research Partial Genealogy of the Whartons Main Political Affiliation: (of Pennsylvania & Delaware) 1763-83 Whig Revolutionary 1789-1823 Republican 1824-33 National Republican ?? 1600 1834-53 Whig ?? 1854- Republican ?? Richard Wharton (1646-83) (Emigrated from Overton, Westmoreland, England to Pennsylvania, 1683) 1650 = ???? (????-at least 1683) Thomas Wharton (1664-1718); (wealthy merchant); (became Quaker) (Philadelphia PA council, 1713-18) = Rachel Thomas (1664-1747) John Wharton 6 Others Joseph Wharton 1700 (1700-37/61?); (saddlemaker) See Carpenter of PA (1707-76); (merchant) (Chester co. PA coroner, 1730-37) Genealogy ("Duke Joseph") = Mary Dobbins Hannah Carpenter = = Hannah Owen (Ogden) (1696-1763) (1711-51) (1720-91) 4 Others Thomas Wharton Samuel Wharton 8 Others Charles Wharton Carpenter Wharton (1735-78); (merchant) (1732-1800); (merchant/landowner) (1742-1836) (1747-80) (signed Non-Importation Agreement, 1765) (PA legislature); (Vandalia Co. promoter) = Hannah Redwood = Elizabeth Davis (PA committee of safety, 1775-76) (PA committee of safety) (1759-96) (1751?-1816) (President PA supreme executive council, 1776-78) (US Continental Congress from Delaware, 1782-83) 1750Susannah Lloyd = = Elizabeth Fishbourne (Southwark district DE justice); (DE judge, 1790-91) (1739-72) (1752-1826) Gen. Robert Wharton 5 Others Lt. Col. Franklin Wharton = Sarah Lewis (1757-1834) (1767-1818) See Lloyd of PA (1732-at least 1762) Genealogy (Mayor Philadelphia PA 15 times (Commandante between 1798-1834) US Marine Corps, 1804-18) -

A Narrative of the Conquest, Division, Settlement, and Transformation of Kentucky

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 Pioneers, proclamations, and patents : a narrative of the conquest, division, settlement, and transformation of Kentucky. Brandon Michael Robison 1986- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Robison, Brandon Michael 1986-, "Pioneers, proclamations, and patents : a narrative of the conquest, division, settlement, and transformation of Kentucky." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1222. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/1222 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PIONEERS, PROCLAMATIONS, AND PATENTS: A NARRATIVE OF THE CONQUEST, DIVISION, SETTLEMENT, AND TRANSFORMATION OF KENTUCKY By Brandon Michael Robison B.A., Southern Adventist University, 2009 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky May 2013 PIONEERS, PROCLAMATIONS, AND PATENTS: A NARRATIVE OF THE CONQUEST, DIVISION, SETTLEMENT, AND TRANSFORMATION OF KENTUCKY By Brandon Michael Robison B.A., Southern Adventist University, 2009 A Thesis Approved on April 26, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: _____________________________ Dr. Glenn Crothers Thesis Director ______________________________ Dr.Garry Sparks ______________________________ Dr.