A52189) (A52189) (A52189

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fish 2002 Tec Doc Draft3

BRITISH COLUMBIA MINISTRY OF WATER, LAND AND AIR PROTECTION - 2002 Environmental Indicator: Fish in British Columbia Primary Indicator: Conservation status of Steelhead Trout stocks rated as healthy, of conservation concern, and of extreme conservation concern. Selection of the Indicator: The conservation status of Steelhead Trout stocks is a state or condition indicator. It provides a direct measure of the condition of British Columbia’s Steelhead stocks. Steelhead Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) are highly valued by recreational anglers and play a locally important role in First Nations ceremonial, social and food fisheries. Because Steelhead Trout use both freshwater and marine ecosystems at different periods in their life cycle, it is difficult to separate effects of freshwater and marine habitat quality and freshwater and marine harvest mortality. Recent delcines, however, in southern stocks have been attributed to environmental change, rather than over-fishing because many of these stocks are not significantly harvested by sport or commercial fisheries. With respect to conseration risk, if a stock is over fished, it is designated as being of ‘conservation concern’. The term ‘extreme conservation concern’ is applied to stock if there is a probablity that the stock could be extirpated. Data and Sources: Table 1. Conservation Ratings of Steelhead Stock in British Columbia, 2000 Steelhead Stock Extreme Conservation Conservation Healthy Total (Conservation Unit Name) Concern Concern Bella Coola–Rivers Inlet 1 32 33 Boundary Bay 4 4 Burrard -

Dionisio Point Excavations

1HE• Publication of the Archaeological Society of Vol. 31 , No. I - 1999 Dionisio Point Excavations ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF &MIDDEN BRITISH COLUMBIA Published four times a year by the Archaeological Society of British Columbia Dedicated to the protection of archaeological resot:Jrces and the spread of archaeological knowledge. Editorial Committee Editor: Heather Myles (274-4294) President Field Editor: Richard Brolly (689-1678) Helmi Braches (462-8942) arcas@istar. ca [email protected] News Editor: Heather Myles Publications Editor: Robbin Chatan (215-1746) Membership [email protected] Sean Nugent (685-9592) Assistant Editors: Erin Strutt [email protected] erins@intergate. be.ca Fred Braches Annual membership includes I year's subscription to [email protected] The Midden and the ASBC newsletter, SocNotes. Production & Subscriptions: Fred Braches ( 462-8942) Membership Fees I SuBSCRIPTION is included with ASBC membership. Individual: $25 Family: $30 . Seniors/Students: $I 8 Non-members: $14.50 per year ($1 7.00 USA and overseas), Send cheque or money order payable to the ASBC to: payable in Canadian funds to the ASBC. Remit to: ASBC Memberships Midden Subscriptions, ASBC P.O. Box 520, Bentall Station P.O. Box 520, Bentall Station Vancouver BC V6C 2N3 Vancouver BC V6C 2N3 SuBMISSIONs: We welcome contributions on subjects germane ASBC on Internet to BC archaeology. Guidelines are available on request. Sub http://home.istar.ca/-glenchan/asbc/asbc.shtml missions and exchange publications should be directed to the appropriate editor at the ASBC address. Affiliated Chapters Copyright Nanaimo Contact: Rachael Sydenham Internet: http://www.geocities.com/rainforest/5433 Contents of The Midden are copyrighted by the ASBC. -

Report Title: Site C Environmental Impact Statement Issuer: BC Hydro and Power Authority, System Engineering Division Date: July 1980

Report Title: Site C Environmental Impact Statement Issuer: BC Hydro and Power Authority, System Engineering Division Date: July 1980 NOTE TO READER: THE FOLLOWING REPORT IS MORE THAN TWO DECADES OLD. INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS REPORT MAY BE OUT OF DATE AND BC HYDRO MAKES NO STATEMENT ABOUT ITS ACCURACY OR COMPLETENESS. USE OF THIS REPORT AND/OR ITS CONTENTS IS AT THE USER’S OWN RISK. During Stage 2 of the Site C Project, studies are underway to update many of the historical studies and information known about the project. The potential Site C project, as originally conceived, will be updated to reflect current information and to incorporate new ideas brought forward by communities, First Nations, regulatory agencies and stakeholders. Today’s approach to Site C will consider environmental concerns, impacts to land, and opportunities for community benefits, and will update design, financial and technical work. PEACE SITE C PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT Part Two Environmental and Socio-Economic Assessment SECTION 5.0 - PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT CONTENTS Section Subject Page 5.1 INTRODUCTI ON 5- 1 5.2 CLIMATIC CONDITIONS 5- 1 5.3 RIVER AND ICE REGIMES 5- 2 5.4 MINERAL, NATURAL GAS AND GRAVEL RESOURCES 5- 3 5.5 PRESENT VALLEY SLOPE STABILITY 5- 3 5.6 FUTURE SHORLINE CONDITIONS 5- 4 SE 7910 5- Part Two SECTION 5.0 PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT 5.1 INTRODUCTION Existing conditions and predicted changes due to the Site C deve 1opment were studi ed for the fo11owi ng aspects of the physica1 environment: 1. Climatic conditions. 2. River regime, sedimentation and ice. -

GMSWORKS-12/13 | Peace and Williston Recreational

GMSWORKS 12/13 – Water License Requirements Peace and Williston Recreational Access Feasibility Study Feasibility Study for Boat Launch Ramps along the Peace River FINAL REPORT 777 W. Broadway Suite 301 Vancouver, BC, V5Z 4J7 In association with March 5, 2010 MN Project 6683 Peace River and Williston Recreational Access Feasibility Study TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PROJECT BACKGROUND ....................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 SCOPE OF WORK ................................................................................................................................. 2 1.3 REPORT ORGANIZATION ....................................................................................................................... 3 2.0 DATA COLLECTION AND ANALYSIS ..................................................................................................................... 4 3.0 INSPECTION FINDINGS OF THE POTENTIAL BOAT LAUNCH RAMP SITES AND EXISTING BOAT LAUNCH FACILITIES ................................................................................................................................................................ 5 3.1 SITE LOCATIONS .................................................................................................................................. 5 3.2 HALFWAY RIVER EXISTING -

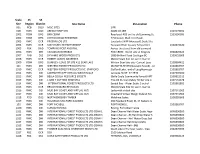

Scale Site SS Region SS District Site Name SS Location Phone

Scale SS SS Site Region District Site Name SS Location Phone 001 RCB DQU MISC SITES SIFR 01B RWC DQC ABFAM TEMP SITE SAME AS 1BB 2505574201 1001 ROM DPG BKB CEDAR Road past 4G3 on the old Lamming Ce 2505690096 1002 ROM DPG JOHN DUNCAN RESIDENCE 7750 Lower Mud river Road. 1003 RWC DCR PROBYN LOG LTD. Located at WFP Menzies#1 Scale Site 1004 RWC DCR MATCHLEE LTD PARTNERSHIP Tsowwin River estuary Tahsis Inlet 2502872120 1005 RSK DND TOMPKINS POST AND RAIL Across the street from old corwood 1006 RWC DNI CANADIAN OVERSEAS FOG CREEK - North side of King Isla 6046820425 1007 RKB DSE DYNAMIC WOOD PRODUCTS 1839 Brilliant Road Castlegar BC 2503653669 1008 RWC DCR ROBERT (ANDY) ANDERSEN Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1009 ROM DPG DUNKLEY- LEASE OF SITE 411 BEAR LAKE Winton Bear lake site- Current Leas 2509984421 101 RWC DNI WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. MAHATTA RIVER (Quatsino Sound) - Lo 2502863767 1010 RWC DCR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. STAFFORD Stafford Lake , end of Loughborough 2502863767 1011 RWC DSI LADYSMITH WFP VIRTUAL WEIGH SCALE Latitude 48 59' 57.79"N 2507204200 1012 RWC DNI BELLA COOLA RESOURCE SOCIETY (Bella Coola Community Forest) VIRT 2509822515 1013 RWC DSI L AND Y CUTTING EDGE MILL The old Duncan Valley Timber site o 2507151678 1014 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD Sandal Bay - Water Scale. 2 out of 2502861881 1015 RWC DCR BRUCE EDWARD REYNOLDS Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1016 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Ladysmith virtual site 2507541962 1017 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Coastland Virtual Weigh Scale at Mu 2507541962 1018 RTO DOS NORTH ENDERBY TIMBER Malakwa Scales 2508389668 1019 RWC DSI HAULBACK MILLYARD GALIANO 200 Haulback Road, DL 14 Galiano Is 102 RWC DNI PORT MCNEILL PORT MCNEILL 2502863767 1020 RWC DSI KURUCZ ROVING Roving, Port Alberni area 1021 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD-DEAN 1 Dean Channel Heli Water Scale. -

View: Local and Traditional Knowledge in the Liard River Watershed

Literature Review: Local and Traditional Knowledge in the Liard River Watershed Literature Review Local and Traditional Knowledge In the Liard River Watershed ______________________________________ Brenda Parlee I i Parlee, B. ©2019 Tracking Change Project, University of Alberta. All rights reserved. Compiled October 2016. ii Literature Review: Local and Traditional Knowledge in the Liard River Watershed TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ......................................................................................................................... iii Tables and Figures .................................................................................................................................... iv Summary Points ............................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 3 The Liard River Basin ............................................................................................................................... 3 Methods .......................................................................................................................................... 3 Searching for Secondary Sources of Publicly Available Traditional Knowledge ................ 3 Oral Histories ........................................................................................................................................ -

Blueberry River First Nations

SITE C CLEAN ENERGY PROJECT BLUEBERRY RIVER FIRST NATIONS COMMUNITY BASELINE AMENDMENT REPORT Prepared for: BC Hydro Power and Authority 333 Dunsmuir Street Vancouver, BC V6B 5R3 Prepared by: Golder Associates 500 - 4260 Still Creek Drive, Burnaby, British Columbia, V5C 6C6 Tel: +1 (604) 296 4200 Fax: +1 (604) 298 5253 and BC Hydro Power and Authority 600, Four Bentall Centre 1055 Dunsmuir Street PO Box 49260 Vancouver, B.C. V7X 1V5 May 2013 Site C Clean Energy Project - Aboriginal Group Amendment Report Community Baseline Amendment Report – Blueberry River First Nations 1 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................... 3 2 2. Consideration of New Information by VC ......................................................... 5 3 12. Fish and Fish Habitat .......................................................................................... 6 4 13. Vegetation and Ecological Plant Communities ................................................ 7 5 14. Wildlife Resources .............................................................................................. 9 6 15. Greenhouse Gases ............................................................................................ 12 7 16. Local Government Revenue ............................................................................. 13 8 17. Labour Market .................................................................................................... 14 9 18. Regional Economic Development .................................................................. -

Mha Boundaries

BC Hockey 6671 Oldfield Road Saanichton BC V8M 2A1 [email protected] www.bchockey.net Ph: 250.652.2978 Fax: 250.652.4536 MHA BOUNDARIES MHA Boundaries 100 Mile House and The boundaries of the 100 Mile House MHA shall be north from the point where the District Minor Hockey Cariboo Regional District's southern boundary intersects the 122 degrees meridian, east along Association the Cariboo Regional District's southern boundary to a point directly south of where Highway 97 intersects the 52 degrees N. Lat, north to 52 degrees N lat, eastward to 121 degrees w Long, north to the height of land between the Canim Lake and Horsefly River/Moffat Creek drainage areas to the head of Spanish Creek and the Cariboo Regional District boundary. The boundary continues south along the Cariboo Regional District boundary to Lac des Roches and continues south to 51 degrees 15'N. Lat., west to 122 degrees W. Long and north to the Cariboo Regional District boundary. Abbotsford Female City of Abbotsford and Sumas Mountain unorganized territory. Transitional Provision: Hockey Association For the 07-08 season, Female players whose parents are residents within the draw zone and who were last registered with Abbotsford MHA shall be permitted a onetime option to register with Abbotsford Female HA without having to process an Application for Player Movement under the "No Female Team" section. Abbotsford Female IHA shall supply the PCAHA Executive Director with a list of all players taking this option. Abbotsford Minor The Municipality of Abbotsford and Sumas Mountain unorganized territory; for exception, see Hockey Association Aldergrove MHA Alberni Valley Minor From Pacific Rim National Park in the west including the towns of Tofino, Ucluelet and Hockey Association Bamfield to the Cameron Lake Boundary in the east. -

A History of Fish in the Northeastern British Columbia

HISTORICAL FISHERIES INFORMATION FROM THE MUSKWA-KECHIKA MANAGEMENT AREA Prepared By: Alicia Woods SS#2 Site 13 Comp 17 Fort St. John, BC V1J 4M7 For: Fisheries Branch Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks Rm. 400 10003-110th Avenue Fort St. John, BC V1J 6M7 January 2001 Muskwa-Kechika Historical Fisheries Research Project SUMMARY The primary purpose of this research project was to compile and preserve historical fisheries information within the Muskwa-Kechika Management Area. This report outlines and describes, by watershed, fisheries related activities that took place over the past decades. Information gathered for this project came from personal interviews and other research. Interviews were conducted with persons from Fort St. John, Fort Nelson, Dawson Creek and other communities. The expectation of this project is to document and preserve information, that would otherwise be lost, and make it accessible for further research. In addition to preserving the past, this research will be able to provide a different outlook on past fisheries issues, and possibly bring forth new ideas and management strategies. Funding for this project was obtained through an application from BC Environment, Fisheries Section, Fort St. John, to the Muskwa-Kechika Trust Fund. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Much appreciation and thanks to Nick Baccante, for direction and knowledge on this project, Paul Mitchell-Banks for his knowledge and including me on his many excursions, the Fish and Wildlife staff at the Ministry of Environment, Lands and Parks, and Rob Woods for his immeasurable amount of knowledge of the area. The author also wishes to acknowledge the Guide Outfitters of northeastern British Columbia, Fort Nelson First Nations Band, Prophet River First Nations Band and the many locals that volunteered their time and offered their knowledge to this project. -

Peace River Angling and Recreational-Use Creel Survey 2008 Interim Year 1 Report

EA 3078 Peace River Angling and Recreational-Use Creel Survey 2008 Interim Year 1 Report Prepared for: BC Hydro 8th Floor, 333 Dunsmuir Street Vancouver, BC Prepared by: D. Robichaud, M. Mathews, A. Blakley and R. Bocking 9768 Second Street Sidney, British Columbia, V8L 3Y8 June 2009 This report was prepared for the exclusive use of BC Hydro, its assignees and representatives, and is intended to provide results of baseline data collection for the Peace River. This report is not intended to identify or evaluate potential effects that may occur at or near the Project area as a result of completion of the proposed project. The findings and conclusions documented in this baseline data report have been prepared for the specific application to this Project and have been developed in a manner consistent with the level of care normally exercised by environmental professionals currently practicing under similar conditions in the jurisdiction. Any use which a third party makes of this report or any reliance on or decisions to be made based on it, are the responsibility of such third parties. LGL Limited accepts no responsibility for damages, if any, suffered by any third party as a result of decisions made or actions based on this report. Peace River Angling and Recreational-Use Creel Survey EA3078 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sport fishing and river-based recreation are important activities to the communities and economy of the Peace Region and BC Hydro is interested in determining how the potential construction and operation of the Site C dam would change the pattern of river-use. -

DFD 1I1~[Imu11~R111rr"" 02006214

CAN 8 1968-2 DFD 1i1~[imu11~r111rr"" 02006214 COMPUTOR CODE OF SALMON INVESTIGATION LOCATIONS IN BRITISH COLUMBIA UBRARY ADA FISHERlf S AND OCEANS CAN 4r;. : -- w. HASTINGS ST. Gl VA~ s --. .:R. BC CANADA V6B 5 (604) 6SS-3851 Department of Fisheries of Canada Vancouver, B. C. June, 1968 , ., SH 349 P3 C35 1968 e .... .... INTRODUCTION The folloWing location code · is based db the cbde which was originaily prepared by perso.Ymel of the Fisheries Resear.ch Board of Canada in 1961 an·d revised in 1965. This : . ..... code has been expanded iJ:1 mo qt .· stat;istical areas and in ·. some instances, in order to meet the specific requirements of Resource Development personnel~ .. t :he code has been revfsed substantially~ AREA 01 DIXON ENTRANCE (Statistical Area 1) Sub Area 1 Outside western net boundary 00. Sub Area 2 Inside western net boundary . 00 01 Frederick Is. Sub Area 3 Outside northern net boundary 00 01 Langara T.s. 02 Seven Mile (Wiah Pt.) 03 Cape· Muzon · Sub Are~ 4 Inside northern n~t boundary .00 01 Langara 02 Jallun River 03 Shag Rock 04 Seven Mile (W1ah Pt.) Sub Area· 5 Naden Harbour . 00 ·01 Naden Harbour. 02 Stanley Creek 03 Naden River 04 Collison River Sub Area 6 Masset Inlet 00 01 Masset Inlet 02 Masset Bar 03 Ain River 04 Dinan Creek 05 McLinton Creek 06 A~un River and Lake 07 Datlamen River 08 Mamin River 09 Yakoun River and Lake 10 Kumdis River AREA 02 QUEEN CHARLOTTE ISLANDS Sub Area· 1 2 A West outside net boundary 00 :Sub Area 2 2 A West inside net boundary . -

The Grasslands of British Columbia

The Grasslands of British Columbia The Grasslands of British Columbia Brian Wikeem Sandra Wikeem April 2004 COVER PHOTO Brian Wikeem, Solterra Resources Inc. GRAPHICS, MAPS, FIGURES Donna Falat, formerly Grasslands Conservation Council of B.C., Kamloops, B.C. Ryan Holmes, Grasslands Conservation Council of B.C., Kamloops, B.C. Glenda Mathew, Left Bank Design, Kamloops, B.C. PHOTOS Personal Photos: A. Batke, Andy Bezener, Don Blumenauer, Bruno Delesalle, Craig Delong, Bob Drinkwater, Wayne Erickson, Marylin Fuchs, Perry Grilz, Jared Hobbs, Ryan Holmes, Kristi Iverson, C. Junck, Bob Lincoln, Bob Needham, Paul Sandborn, Jim White, Brian Wikeem. Institutional Photos: Agriculture Agri-Food Canada, BC Archives, BC Ministry of Forests, BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, and BC Parks. All photographs are the property of the original contributor and can not be reproduced without prior written permission of the owner. All photographs by J. Hobbs are © Jared Hobbs. © Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia 954A Laval Crescent Kamloops, B.C. V2C 5P5 http://www.bcgrasslands.org/ All rights reserved. No part of this document or publication may be reproduced in any form without prior written permission of the Grasslands Conservation Council of British Columbia. ii Dedication This book is dedicated to the Dr. Vernon pathfinders of our ecological Brink knowledge and understanding of Dr. Alastair grassland ecosystems in British McLean Columbia. Their vision looked Dr. Edward beyond the dust, cheatgrass and Tisdale grasshoppers, and set the course to Dr. Albert van restoring the biodiversity and beauty Ryswyk of our grasslands to pristine times. Their research, extension and teaching provided the foundation for scientific management of our grasslands.