Re-Imagining Russian Nuclear Weapons Scientists Hugh Gusterson Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

After the Meltdown

Tulsa Law Review Volume 45 Issue 3 Regulation and Recession: Causes, Effects, and Solutions for Financial Crises Spring 2010 After the Meltdown Daniel J. Morrissey Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Daniel J. Morrissey, After the Meltdown, 45 Tulsa L. Rev. 393 (2013). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.utulsa.edu/tlr/vol45/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by TU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Tulsa Law Review by an authorized editor of TU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Morrissey: After the Meltdown AFTER THE MELTDOWN Daniel J. Morrissey* We will not go back to the days of reckless behavior and unchecked excess that was at the heart of this crisis, where too many were motivated only by the appetite for quick kills and bloated bonuses. -President Barack Obamal The window of opportunityfor reform will not be open for long .... -Princeton Economist Hyun Song Shin 2 I. INTRODUCTION: THE MELTDOWN A. How it Happened One year after the financial markets collapsed, President Obama served notice on Wall Street that society would no longer tolerate the corrupt business practices that had almost destroyed the world's economy. 3 In "an era of rapacious capitalists and heedless self-indulgence," 4 an "ingenious elite" 5 set up a credit regime based on improvident * A.B., J.D., Georgetown University; Professor and Former Dean, Gonzaga University School of Law. This article is dedicated to Professor Tom Holland, a committed legal educator and a great friend to the author. -

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia

Escalation Control and the Nuclear Option in South Asia Michael Krepon, Rodney W. Jones, and Ziad Haider, editors Copyright © 2004 The Henry L. Stimson Center All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Henry L. Stimson Center. Cover design by Design Army. ISBN 0-9747255-8-7 The Henry L. Stimson Center 1111 19th Street NW Twelfth Floor Washington, DC 20036 phone 202.223.5956 fax 202.238.9604 www.stimson.org Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................. v Abbreviations..................................................................................................... vii Introduction......................................................................................................... ix 1. The Stability-Instability Paradox, Misperception, and Escalation Control in South Asia Michael Krepon ............................................................................................ 1 2. Nuclear Stability and Escalation Control in South Asia: Structural Factors Rodney W. Jones......................................................................................... 25 3. India’s Escalation-Resistant Nuclear Posture Rajesh M. Basrur ........................................................................................ 56 4. Nuclear Signaling, Missiles, and Escalation Control in South Asia Feroz Hassan Khan ................................................................................... -

Knights for Israel Honored at Camera Gala 2018 a Must-See Film

Editorials ..................................... 4A Op-Ed .......................................... 5A Calendar ...................................... 6A Scene Around ............................. 9A Synagogue Directory ................ 11A JTA News Briefs ........................ 13A WWW.HERITAGEFL.COM YEAR 42, NO. 40 JUNE 8, 2018 25 SIVAN, 5778 ORLANDO, FLORIDA SINGLE COPY 75¢ JNF’s Plant Your Way website NEW YORK—Jewish Na- it can be applied to any Jewish tional Fund revealed its new National Fund trip and the Plant Your Way website that Alexander Muss High School easily allows individuals to in Israel (AMHSI-JNF) is a raise money for a future trip huge bonus because donors to Israel while helping build can take advantage of the 100 the land of Israel. percent tax deductible status First introduced in 2000, of the contributions.” Plant Your Way has allowed Some of the benefits in- many hundreds of young clude: people a personal fundraising • Donations are 100 percent platform to raise money for a tax deductible; trip to Israel while giving back • It’s a great way to teach at the same time. Over the children and young adults the last 18 years, more than $1.3 basics of fundraising, while million has been generated for they build a connection to Jewish National Fund proj- Israel and plan a personal trip Knights for Israel members (l-r): Emily Aspinwall, Sam Busey, Jake Suster, Jesse Benjamin Slomowitz and Benji ects, typically by high school to Israel; Osterman, accepted the David Bar-Ilan Award for Outstanding Campus Activism. students. The new platform • Funds raised can be ap- allows parents/grandparents plied to any Israel trip (up to along with family, friends, age 30); coworkers and classmates • Participant can designate Knights for Israel honored to open Plant Your Way ac- to any of Jewish National counts for individuals from Fund’s seven program areas, birth up to the age of 30, and including forestry and green at Camera Gala 2018 for schools to raise money for innovation, water solutions, trips as well. -

UNDERSTANDING POWER the INDISPENSABLE CHOMSKY Edited by Peter R

THE FOOTNOTES FOR: UNDERSTANDING POWER THE INDISPENSABLE CHOMSKY Edited by Peter R. Mitchell and John Schoeffel. Preface 1. For George Bush's statement, see "Bush's Remarks to the Nation on the Terrorist Attacks," New York Times, September 12, 2001, p. A4. For the quoted analysis from the New York Times's first "Week in Review" section following the September 11th attacks, see Serge Schmemann, "War Zone: What Would ‘Victory’ Mean?," New York Times, September 16, 2001, section 4, p. 1. Understanding Power: Preface Footnote Chapter One Weekend Teach-In: Opening Session 1. On Kennedy's fraudulent "missile gap" and major escalation of the arms race, see for example, Fred Kaplan, Wizards of Armageddon, New York: Simon & Schuster, 1983, chs. 16, 19 and 20; Desmond Ball, Politics and Force Levels: The Strategic Missile Program of the Kennedy Administration, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980, ch. 2. On Reagan's fraudulent "window of vulnerability" and "military spending gap" and the massive military buildup during his first administration, see for example, Jeff McMahan, Reagan and the World: Imperial Policy in the New Cold War, New York: Monthly Review, 1985, chs. 2 and 3; Franklyn Holzman, "Politics and Guesswork: C.I.A. and D.I.A. estimates of Soviet Military Spending," International Security, Fall 1989, pp. 101-131; Franklyn Holzman, "The C.I.A.'s Military Spending Estimates: Deceit and Its Costs," Challenge, May/June 1992, pp. 28-39; Report of the President's Commission on Strategic Forces, Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, April 1983, especially pp. 7-8, 17, and Brent Scowcroft, "Final Report of the President's Commission on Strategic Forces," Atlantic Community Quarterly, Vol. -

“Reviving Democracy: Election Reform in Virginia”

Charlottesville Area E-mail: Visit Our Website: [email protected] lwv-cva.org League of Women Voters Mailing Address: PO Box 2786 Newsletter Charlottesville, VA 22902 November 2018 Telephone: 434 237-3264 Tuesday November 6 is Election Day! Polls will be open from 6 am to 7 pm on November 6. More information about candidates, the two proposed constitutional amendments, and voter IDs can be found on the state election website: elections.virginia.gov LWV CVA Sunday Seminar “Reviving Democracy: Election Reform in Virginia” Sunday, November 18, 2018 2 to 4 pm at CitySpace on the Downtown Mall Guest Speakers: Ryan Snow and Sally Hudson In an era of divisive politics, voters are hungry for concrete proposals to promote more competitive and representative elections. Virginia has several potential reforms coming to its General Assembly in January 2019. Join us on Sunday, November 18, 2018, for a discussion of key bills up for debate this legislative session, from ranked choice voting to campaign finance reform. Our guest speakers are: Sally Hudson, economist and assistant professor of Public Policy at UVa. In 2017, she founded FairVote Virginia, [https://www.fairvote.org/] a cross-partisan coalition working to advance ranked choice voting in Virginia. Ryan Snow is a civil rights lawyer and advocate focused on voting rights, redistricting, and campaign finance reform. A 2018 graduate of UVa’s School of Law, Ryan now serves as Legal Fellow in the Voting Rights Project of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law. Page | 1 – November 2018 President’s Message – Dear Fellow League members, Our October Sunday Seminar about the ERA ratification effort made me proud to be a member of our 98-year-old organization. -

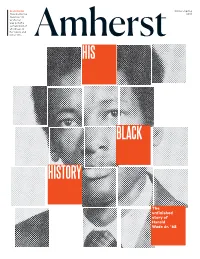

WEB Amherst Sp18.Pdf

ALSO INSIDE Winter–Spring How Catherine 2018 Newman ’90 wrote her way out of a certain kind of stuckness in her novel, and Amherst in her life. HIS BLACK HISTORY The unfinished story of Harold Wade Jr. ’68 XXIN THIS ISSUE: WINTER–SPRING 2018XX 20 30 36 His Black History Start Them Up In Them, We See Our Heartbeat THE STORY OF HAROLD YOUNG, AMHERST- WADE JR. ’68, AUTHOR OF EDUCATED FOR JULI BERWALD ’89, BLACK MEN OF AMHERST ENTREPRENEURS ARE JELLYFISH ARE A SOURCE OF AND NAMESAKE OF FINDING AND CREATING WONDER—AND A REMINDER AN ENDURING OPPORTUNITIES IN THE OF OUR ECOLOGICAL FELLOWSHIP PROGRAM RAPIDLY CHANGING RESPONSIBILITIES. BY KATHARINE CHINESE ECONOMY. INTERVIEW BY WHITTEMORE BY ANJIE ZHENG ’10 MARGARET STOHL ’89 42 Art For Everyone HOW 10 STUDENTS AND DOZENS OF VOTERS CHOSE THREE NEW WORKS FOR THE MEAD ART MUSEUM’S PERMANENT COLLECTION BY MARY ELIZABETH STRUNK Attorney, activist and author Junius Williams ’65 was the second Amherst alum to hold the fellowship named for Harold Wade Jr. ’68. Photograph by BETH PERKINS 2 “We aim to change the First Words reigning paradigm from Catherine Newman ’90 writes what she knows—and what she doesn’t. one of exploiting the 4 Amazon for its resources Voices to taking care of it.” Winning Olympic bronze, leaving Amherst to serve in Vietnam, using an X-ray generator and other Foster “Butch” Brown ’73, about his collaborative reminiscences from readers environmental work in the rainforest. PAGE 18 6 College Row XX ONLINE: AMHERST.EDU/MAGAZINE XX Support for fi rst-generation students, the physics of a Slinky, migration to News Video & Audio Montana and more Poet and activist Sonia Sanchez, In its interdisciplinary exploration 14 the fi rst African-American of the Trump Administration, an The Big Picture woman to serve on the Amherst Amherst course taught by Ilan A contest-winning photo faculty, returned to campus to Stavans held a Trump Point/ from snow-covered Kyoto give the keynote address at the Counterpoint Series featuring Dr. -

Backyard of Party Booze, Grilling Ryan and Other Things You'll Enjoy Reynolds

LEBRON JAMES: THE STYLISH BALLER OLIVIA WILDE DOES GYMNASTICS FOR US! WIN AN iPAD2 P.113 SHARPLOOK BETTER · FEEL BETTER · KNOW MORE EVERYONE HOW TO THROW WANTS A THE ULTIMATE PIECE BACKYARD OF PARTY BOOZE, GRILLING RYAN AND OTHER THINGS YOU'LL ENJOY REYNOLDS THE MOST BEAUTIFUL SURFING IN THE LAND THE UFC’S CAR EVER MADE OF BLOOD DIAMONDS IMAGE PROBLEM YOUR NEW SUMMER WARDROBE HAS ARRIVED JUNE- JU LY 2011 ONLINE SHARPFORMEN.COM Display until July 31ST, 2011 $4.95 LEBRON JAMES: THE STYLISH BALLER OLIVIA WILDE DOES GYMNASTICS FOR US! WIN AN iPAD2 P.113 SHARPLOOK BETTER · FEEL BETTER · KNOW MORE EVERYONE WANTS A FATHER'S PIECE DAY GUIDE OF GIFTS FOR RYAN 25DADS REYNOLDS YOUR NEW SUMMER SURFING IN THE LAND THE UFC’S WARDROBE HAS ARRIVED OF BLOOD DIAMONDS IMAGE PROBLEM HOW TO THROW THE ULTIMATE BACKYARD PARTY ONLINE SHARPFORMEN.COM 2011 JUNE-JULY B:16.25 in T:16 in S:15 in Converts gasoline to adrenaline. With its bold, dynamic AMG styling, the all-new 2012 SLK 350 instantly attracts attention. And with our dynamic handling package and 302 horsepower at your disposal, the ride is as exhilarating as its look. For ultimate closed-top cruising, raise the power retractable vario-roof and witness MAGIC SKY CONTROL – our innovative panoramic sunroof that adjusts from tinted to clear at the touch of a button. Visit mercedes-benz.ca/slk T:10.75 in S:9.75 in B:11 in © 2011 Mercedes-Benz Canada Inc. F:8 in F:8 in Ad Number: MBZ_CRC_P05938SH4 Publication(s): Sharp This proof was produced This ad prepared by: SGL Communications • 2 Bloor St. -

Spying on Friends?: the Franklin Case, AIPAC, and Israel

International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, 19: 600–621, 2006 Copyright # Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0885-0607 print=1521-0561 online DOI: 10.1080/08850600600829809 STE´ PHANE LEFEBVRE Spying on Friends?: The Franklin Case, AIPAC, and Israel On 4 August 2005, U.S. Department of Defense official Lawrence Franklin and former American–Israeli Political Action Committee (AIPAC) staffers Steve Rosen and Keith Weissman were indicted on one or several of the following counts: conspiracy to communicate national defense information to persons not entitled to receive it; communication of national defense information to persons not entitled to receive it; and conspiracy to communicate classified information to agents of a foreign government, publicly identified as Israel. Franklin pleaded guilty and cooperated with the authorities, and was subsequently sentenced to a 12-year prison term. As of this writing, Rosen’s and Weissman’s trial was scheduled to start in August 2006. When the story of an investigation into Franklin’s communication of classified information to Rosen and Weissman surfaced, the immediate widely held assumption was that Israel was the ultimate beneficiary. This belief was reinforced with the disclosure that the compromised classified information was related to issues of immediate interest to the Jewish state, including Iran’s nuclear ambitions and the situation in Iraq. But doubts were expressed, to the effect that the cozy relationship between Israel and the United States would hardly necessitate such an intelligence-gathering operation on U.S. soil. Nevertheless, the question of Israel’s precise role in the affair remains unanswered, but for the exception that Franklin told the U.S. -

October 1, 1997 Errors and Omissions in One Point Safe1 by Thomas B

October 1, 1997 Errors and Omissions in One Point Safe1 by Thomas B. Cochran and Christopher E. Paine Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. Considerable publicity has been given to three recent works involving Andrew and Leslie Cockburn: their book, One Point Safe, a movie The Peacemaker, and a 60 Minutes piece produced by Ms. Cockburn that aired on September 14th. The centerpiece of the 60 Minutes segment was an interview with General Alexander Lebed, a former Russian National Security Council secretary, who claimed that 100 or more suitcase-sized atomic demolition munitions could not be accounted for. While The Peacemaker is pure Hollywood, the book jacket’s subtitle calls One Point Safe, “A True Story,” though this is not repeated on the title page. Also on the jacket is a gold medallion , with an advertisement for the movie: “The Story That Inspired The Peacemaker Now a Major Motion Picture from Dream Works Pictures”. All in all, a formidable example of synergistic promotion. What concerns us here is the book, and the degree to which it is “A True Story.” To its credit the book contains some new and interesting, albeit undocumented information related to several nuclear material smuggling cases. But, unfortunately, it also contains technical errors and historical inaccuracies, many of which we have enumerated below. In fact , the errors in the book are so numerous that they call into question the accuracy of those parts of the book that appear to convey significant new information. One comes away from reading the book with the impression that it was inspired by the movie treatment, rather than the other way around. -

Rotunda Library, Special Collections, and Archives

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Rotunda Library, Special Collections, and Archives 9-24-2018 Rotunda - Vol 97, no 5 - Sep 24, 2018 Longwood University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/rotunda TheROTUNDA Ordering pumpkin spice everything since 1920 PAGE 3 NEWS: Leslie Cockburn visits Longwood for rally DISCOVERING YOUR PAGE 4 A&E: Youtubers IDENTITY THROUGH profiting off of fake views “TRANSLATIONS” PAGE 6 A PREVIEW OPINIONS: Trump’s tweets ignore SEPTEMBER 24, 2018 hurricane victims VOL 97. ISSUE 5 GISELLE VELASQUEZ | THE ROTUNDA 02 > NEWS TheRotundaOnline.com EDITORIAL BOARD 2018 In SGA: CHRISTINE RINDFLEISCH Title IX editor-in-chief ERIN EATON presentation managing editor by Rachael Poole | Opinions Editor | @rapoole17 JEFF HALLIDAY, MIKE MERGEN AND CLINT WRIGHT n this week’s Student faculty advisers Government Association (SGA) NEWS ROTUNDA Imeeting, Associate Director of Conduct and Integrity Jen Fraley JESSE PLICHTA-KELLAR STUDIOS and University Clery and Title IX editor NICOLE DEL ROSARIO Coordinator Lindsey Moran gave A&E executive producer a presentation on Title IX. The EVA WITTKOSKI | THE ROTUNDA ALAINA JACQUES presentation gave information on the Jen Fraley, associate dean of Conduct and JACOB DILANDRO Integrity Deputy Title IX Coordinator, talks staff resources, elements and policies of editor about the sexual misconduct policy and ELLIE STUCK TAIYA JARRETT Title IX. resources available to help prevent sexual staff staff According to Fraley, Title IX covers misconduct. TJ WENGERT LEDANIEL JACKSON access to higher education, athletics, staff staff career education, employment, sexual mandatory training as responsible AUTUMN HIGH harassment and financial aid. OPINIONS staff employees. -

The NBC News Midterm Election Briefing Book

The NBC News Midterm Midterm Elections Election Briefing 2018 Book Created by the By Carrie Dann, Mark Murray and Chuck Todd. NBC News Political Unit Other contributors include: NBC’s Ben Kamisar, Hannah Coulter and Mike Memoli TABLE OF CONTENTS 2018: WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT THE BATTLE FOR CONTROL………….………………..……………………………2 The House…………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………..……………………2 The Senate………………………………………………………………..………………………………………………………………………3 The governor races…………………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………….…4 WHAT’S AT STAKE ……………………………………..……………………………………………………..…………………………………………5 THE TRUMP EFFECT ……………………………………..………………………………………………….……………………………………….…6 KEY ISSUES (that aren’t Trump) ……………………………………………………………………..…………………..…………..………..…7 MAJOR TRENDS, BY THE NUMBERS …………………………………………………………………..…….………..……………………….8 Female candidates……………………………………..……………………………………………….……………………………………8 Other key stats (veterans, millennials and more)……………………………………………..……………….……………..9 BARRIER BREAKERS: CANDIDATES WHO WOULD MAKE HISTORY …………………………………..…………….……………10 THE PATH TO A HOUSE MAJORITY — A ROAD MAP TO FOLLOW AS POLLS CLOSE…….………………………………….11 Seats to watch: Democrats on defense……………………..………….………………………………………………………..11 Seats to watch: The most probable flips ……………………..…………………………….………….…….………………..11 Seats to watch: The majority makers…………….………………………………………………………………..………………12 Seats to watch: Adding to a majority — the beginning of a big wave ….………………………..……..…………13 Seats to watch: Tsunami alert! ….…………………………………………………………………………………..……………….13 VIEWERS’ GUIDE -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 117 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 167 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 4, 2021 No. 139 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Friday, August 6, 2021, at 12 p.m. Senate WEDNESDAY, AUGUST 4, 2021 The Senate met at 10:30 a.m. and was to the Senate from the President pro A bill (H.R. 3684) to authorize funds for called to order by the Honorable BEN tempore (Mr. LEAHY). Federal-aid highways, highway safety pro- RAY LUJA´ N, a Senator from the State The senior legislative clerk read the grams, and transit programs, and for other of New Mexico. following letter: purposes. Pending: f U.S. SENATE, PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, Schumer (for Sinema) amendment No. 2137, PRAYER Washington, DC, August 4, 2021. in the nature of a substitute. To the Senate: Carper-Capito amendment No. 2131 (to The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, amendment No. 2137), to strike a definition. fered the following prayer: of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby Carper (for Johnson) amendment No. 2245 Let us pray. appoint the Honorable BEN RAY LUJA´ N, a (to amendment No. 2137), to prohibit the can- Eternal God, in these challenging Senator from the State of New Mexico, to cellation of contracts for physical barriers days, our hearts are steadfast toward perform the duties of the Chair. and other border security measures for which funds already have been obligated and You.