Experiments In/Of Realism— an Abiding and Evolving Notion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ben Cogan 2015 - Freelance Casting Director

Ben Cogan 2015 - Freelance Casting Director 2016 Trendy (Feature Film) Executive Producer: Marilena Parouti Director: Louis Lagayette 2016 Son of Perdition (Short Film) Producer: Alex Carapuig Director: Matthew Harrison 2015 Just Charlie (Feature Film) Executive Producer: Karen Newman Director: Rebekah Fortune 2015 After the Fray (Short Film) Producer: Alex Carapuig Director: Matthew Harrison 2002 - 2015 Casting Director at BBC 2006 – 2015 Casualty (183 episodes and regulars) Executive Producers: Mervyn Watson, Belinda Campbell, Jonathan Phillips and Oliver Kent Series Producers: Jane Dauncey, Oliver Kent, Nikki Wilson and Erika Hossington Producers: Various Directors: Various BAFTA nominations for ‘Continuing Drama’ in 2007 (won), 2009, 2010, 2011, 2014 and 2015. 2009 Wish 143 (Short Film) Producer: Samantha Waite Director: Ian Barnes Oscar nominated. 2008 Kiss of Death (TV Movie) Executive Producer: Patrick Spence Producer: Jane Steventon Director: Paul Unwin 2007 The Real Deal Executive Producer: Will Trotter Producer: Ben Bickerton Director: Ian Barnes 2002 – 2006 Doctors (345 episodes and regulars) Executive Producers: Carson Black & Will Trotter Series Producers: Beverley Dartnall Producers: Various Directors: Various 2005 The Trouble with George Executive Producer: Mal Young & Serena Cullen Producer: Sam Hill Director: Matthew Parkhill 2000 – 2002 Casting Assistant at BBC EastEnders (225 episodes) Executive Producer: John Yorke Series Producer: Lorraine Newman Producers: Various Directors: Various Holby City (38 episodes) Executive Producer: Mal Young Series Producer: Kathleen Hutchinson Producers: Various Directors: Various In Deep (4 episodes) Executive Producer: Mal Young Producer: Steve Lanning Director: Colin Bucksey Waking the Dead (4 episodes) Executive Producer: Alexei de Keyser Producer: Joy Spink Director: Robert Knights & Gary Love EastEnders: The Return of Nick Cotton Executive Producers: Mal Young & John Yorke Producer: Beverley Dartnall Director: Chris Bernard . -

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY of TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS for the 44Th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS

THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES ANNOUNCES NOMINATIONS FOR THE 44th ANNUAL DAYTIME EMMY® AWARDS Daytime Emmy Awards to be held on Sunday, April 30th Daytime Creative Arts Emmy® Awards Gala on Friday, April 28th New York – March 22nd, 2017 – The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS) today announced the nominees for the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy® Awards. The awards ceremony will be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Sunday, April 30th, 2017. The Daytime Creative Arts Emmy Awards will also be held at the Pasadena Civic Auditorium on Friday, April 28th, 2017. The 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Award Nominations were revealed today on the Emmy Award-winning show, “The Talk,” on CBS. “The National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences is excited to be presenting the 44th Annual Daytime Emmy Awards in the historic Pasadena Civic Auditorium,” said Bob Mauro, President, NATAS. “With an outstanding roster of nominees, we are looking forward to an extraordinary celebration honoring the craft and talent that represent the best of Daytime television.” “After receiving a record number of submissions, we are thrilled by this talented and gifted list of nominees that will be honored at this year’s Daytime Emmy Awards,” said David Michaels, SVP, Daytime Emmy Awards. “I am very excited that Michael Levitt is with us as Executive Producer, and that David Parks and I will be serving as Executive Producers as well. With the added grandeur of the Pasadena Civic Auditorium, it will be a spectacular gala that celebrates everything we love about Daytime television!” The Daytime Emmy Awards recognize outstanding achievement in all fields of daytime television production and are presented to individuals and programs broadcast from 2:00 a.m.-6:00 p.m. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

Show of Success TV’S Mal Young Shares His Expertise with Students

theCaledonian News and views for the people of Glasgow Caledonian University April 2013 Glasgow Caledonian University is a registered Scottish charity, number SC021474 Show of success TV’s Mal Young shares his expertise with students In this issue... The heat is on! page three It started with a kiss page four Win a Forever 21 gift card page eight page two £25million has been invested into the Heart of the Campus project. (Facilities) The heat is on for Campus Futures Welcome A new combined heat and power Students’ Association building. The engine, system that will reduce GCU’s carbon which arrived at the beginning of April, will take If this magazine was written by footprint is on target for completion this nine weeks to fit out. “The entire thing needs to Mal Young, then it would probably start May. Work is progressing on the introduction be commissioned before it’s operational – think with a fight. Well, that’s the advice that the of a Combined Heat and Power (CHP) and of it like a test drive – to ensure it’s working the renowned TV producer gave MA TV Fiction district heating supply that will generate on-site way it should,” said Kenny. students for grabbing their viewers’ attention! electricity and heat in a single process. It will There are also plans to use the CHP as a You can read more about Mal’s hugely also supply hot water via a district heating research and teaching tool. “On completion, it successful talk on page five. network to all buildings on campus. -

Liverpool-Village-Walking-Tour-II

Liverpool Walking Tour 2019 History abounds in the Village of Liverpool. Café at 407 – 407 Tulip Street It’s 1929. Billy Frank’s Whale This latest installment of our walking Food Store at 407 Tulip St. is tours takes in houses, green spaces and offering Kellogg’s Corn Flakes for 7 cents and a pound of monuments put on them. butter for 28 cents. Cash only, please. In 1938, Fred Wagner took over the building and Stroll, imagine and enjoy, but please stay on opened Liverpool Hardware. the sidewalk! The hardware store offered tools and housewares, paint and sporting goods, garden- ing supplies, glass installations, pipe threading, and do-it-your- self machine rentals, all in the days before “big box” hardware stores. The building later housed Liverpool Stationers and other businesses. The Café at 407 and the non-profit Ophelia’s Place opened at this location in 2003. Presbyterian Church – 603 Tulip Street The brick First Presbyterian Church building is a church that salt built, dating from 1862 and dedicated on March 6, 1863. Prosperous salt manufacturers contributed heavily to its construction. The architect was Horatio Nelson White (1814- 1892), the architect of Syracuse University’s Hall of Languages, the Gridley Building in downtown Syracuse, and many others. White’s fee was $50. This style is called Second Empire, with its steeply sloping mansard roof and towers. The clock in the tower was installed in 1892, and was originally the official village clock. The Just past Grandy Park is a small neighborhood of modest Village of Liverpool paid $25 per year for use of the tower Greek Revival style houses, likely all built at about the same and maintenance of the clock. -

THE CHILDREN's MEDIA YEARBOOK 20 17 ••• Edit E D B Y Te

The Children’s Media Yearbook 2017 ••• EditEd by tErri LANGAN & frANcEs tAffiNdEr 8 The Children’s Media Yearbook is a publication of The Children’s Media Foundation Director, Greg Childs Administrator, Jacqui Wells The Children’s Media Foundation P.O. Box 56614 London W13 0XS [email protected] First published 2017 © Terri Langan & Frances Taffinder for editorial material and selection © Individual authors and contributors for their contributions All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of The Children’s Media Foundation, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover. ISBN 978-0-9575-5188-6 (paperback) ISBN 978-0-9575518-9-3 (digital version) Book design by Jack Noel Welcome to the 7 2017 Yearbook research Greg Childs can reading improve 38 children’s self esteem? editor’s introduction 9 Dr Barbie Clarke and Alison David Terri Langan the realitY of 41 virtual for kids current Alison Norrington can You groW an open 45 affairs and mind through plaY? industrY neWs Rebecca Atkinson children’s media 11 rethinking 47 foundation revieW toddlers and tv Anna Home OBE Cary Bazalgette concerns about kids and fake neWs 51 media 14 Dr Becky Parry Anne Longfield OBE coming of age online: 54 animation uk 17 the case for Youth-led Helen Brunsdon and Kate O’Connor digital -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

LSDA Prospectus 2021/22

WELCOME Jake Taylor CONTENT About LSDA 4 Our Courses 5 Advanced Diploma 6 Foundation Diploma 10 Part-Time Diploma 13 ACT 101 - Sundays 16 Summer Schools 18 Staff 20 Application & Audition 22 International Students 23 About Us Student Services 24 Resources and Facilities 25 Location 26 Our Students What Our Students Say 28 Alumni 29 Contact 30 ABOUT LSDA OUR COURSES The course aims to provide a comprehensive and rigorous training in the core skills of acting, voice and movement, alongside increasing understanding of the acting industry, which contribute to the formation of a professional actor. Throughout the year students can expect regular classes in acting techniques, Improvisation, text analysis, vocal training, singing, movement and dance, acting for camera techniques among others, all taught by dynamic working professionals. In addition, there are regular performance projects that enable students to consolidate their learning and put into practice the new skills acquired in the many classes undertaken. The rehearsal sessions run on one afternoon a week during the term before becoming full-time for the final 2 weeks. The play chosen to be worked on during term one is often contemporary which is performed in-house to other students and tutors and a classical piece is selected for work on during the second term which is performed in-house before being taken to local schools. In the final term students participate in two different public performance projects, both at professional theatre venues in Central London, giving the students the opportunity to showcase their talent to industry professionals as well as family and friends. -

British Cultural Studies: an Introduction, Third Edition

British Cultural Studies British Cultural Studies is a comprehensive introduction to the British tradition of cultural studies. Graeme Turner offers an accessible overview of the central themes that have informed British cultural studies: language, semiotics, Marxism and ideology, individualism, subjectivity and discourse. Beginning with a history of cultural studies, Turner discusses the work of such pioneers as Raymond Williams, Richard Hoggart, E. P. Thompson, Stuart Hall and the Birmingham Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies. He then explores the central theorists and categories of British cultural studies: texts and contexts; audience; everyday life; ideology; politics, gender and race. The third edition of this successful text has been fully revised and updated to include: • applying the principles of cultural studies and how to read a text • an overview of recent ethnographic studies • a discussion of anthropological theories of consumption • questions of identity and new ethnicities • how to do cultural studies, and an evaluation of recent research method- ologies • a fully updated and comprehensive bibliography. Graeme Turner is Professor of Cultural Studies at the University of Queensland. He is the editor of The Film Cultures Reader and author of Film as Social Practice, 3rd edition, both published by Routledge. Reviews of the second edition ‘An excellent introduction to cultural studies … very well written and accessible.’ John Sparrowhawk, University of North London ‘A good foundation and background to the development -

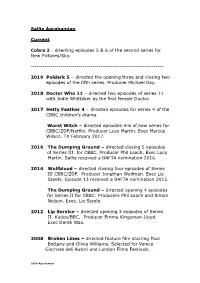

Sallie Aprahamian Current Cobra 2

Sallie Aprahamian Current Cobra 2 - directing episodes 5 & 6 of the second series for New Pictures/Sky. ------------------------------------------------------------------- 2019 Poldark 5 – directed the opening three and closing two episodes of the fifth series. Producer Michael Ray. 2018 Doctor Who 11 – directed two episodes of series 11 with Jodie Whittaker as the first female Doctor. 2017 Hetty Feather 4 – directed episodes for series 4 of the CBBC children’s drama. Worst Witch – directed episodes 4-6 of new series for CBBC/ZDF/Netflix. Producer Lucy Martin. Exec Marcus Wilson. TX February 2017. 2016 The Dumping Ground – directed closing 5 episodes of Series III for CBBC. Producer Phil Leach. Exec Lucy Martin. Sallie received a BAFTA nomination 2016. 2014 Wolfblood – directed closing four episodes of Series III CBBC/ZDF. Producer Jonathan Wolfman. Exec Lis Steele. Episode 13 received a BAFTA nomination 2015. The Dumping Ground – directed opening 4 episodes for Series II for CBBC. Producers Phil Leach and Simon Nelson. Exec. Lis Steele. 2012 Lip Service – directed opening 3 episodes of Series II. Kudos/BBC. Producer Emma Kingsman-Lloyd. Exec Derek Wax. 2008 Broken Lines – directed feature film starring Paul Bettany and Olivia Williams. Selected for Venice Giornate deli Autori and London Films Festivals. Sallie Aprahamian 2005 – 2009 The Bill – directed 8 episodes of the Thames/ITV series. Producers include Lachlan MacKinnon, Lis Steele and Ciara McIlvenny. 2003 Real Men – 2 x 90’ drama by Frank Deasy. Starring Ben Daniels. Producer David Snodin. Exec Frank Deasy and Barbara McKissack. BBC Scotland/BBC 2. RTS nomination. 2002 Outside the Rules – two part ‘Crime Double’ starring Daniela Nardini for BBC1/BBC Wales. -

I Am Writing to You to Express My Deep Concern About the Recent

I am writing to you to express my deep concern about the recent news from the BBC that they have applied to OFCOM to ask if they can reduce news output on the CBBC channel – by axing the main afternoon edition of the much loved Newsround. I am appalled that the BBC would even think this is a good decision. As far as i understand, they say that less children are watching Newsround and more are getting their news online, from the Newsround website and other sources. I cannot understand this reasoning. This is same reasoning they applied to the removal of BBC3 as linear service – and we all know that the end result of that was the BBC reached even less young people. To say more children are watching things online is a cop out. Why are children spending more time watching online? The answer is because they are poorly catered for by linear services. Don’t children spend enough time online as it is? Do we really want to encourage them to spend more time online? Newsround has been a fixture in the CBBC schedule for over 40 years. Surely, this is what the BBC should be spending their money on – a daily news programme for children aged 7- 15. CBBC broadcasts for 14 hours a day- is it really too much to ask that they provide 7 minutes of news in the afternoon / evening? The CBBC channel narrowed its focus to 7-12 year olds in 2013. Some of the continuity presenters can hardly string a legible sentence together and others would be more suited to Cbeebies. -

Philip Harrison

PHILIP HARRISON Height: 6’3 Hair: Light Brown Eyes: blue/grey Training and skills: Trained at A.L.R.A 3 year acting course, Sorrell Carson Stockton Billingham Tech, Foundation drama, 2 yrs. Ken Parkin Fencing (Most Bladed weapons) A.F.A Basic coach Foil, Epee, Sabre. Eskrima (stick fighting). Martial arts: Basic Kung Fu, (Sholin Golden Fist) Karate (Wado Ryu) Progressive combat. Archery. Guitar. Video Production. Juggling, Stilt walking. Film credits include: The Boy on the Bus Simon Pitts Flourishing Pictures Harrigans Nick Tall Trees Films Sleepworking Gavin Williams Hook Pictures Television credits include The Dumping Ground Di Patrick BBC Inspector George Gently Gillies Mackinnon BBC Inside Out Dan Farthing BBC Vera Paul Whittington ITV Emmerdale John Anderson/Micky Jones Granada Television ('North') Byker Grove Rob Bailey BBC/Zenith North ('Ollie’s Dad') Badger Paul Harrison BBC/Zenith North ('Egger') Fighting for Gemma Julian Jarrold Granada ('Frank') Clock Shock 999 Katie Thomas BBC ('Father') Per Chance To Dream Tim Putnam Channel 4 ('Hobbs') Heartbeat Tim Dowd Yorkshire Whispers of the Rock David Sands Border TV ('Lt Wallingford') Glass Virgin Sarah Hellings Tyne Tees ('Big fella') Harry Mary MacMurray BBC Commercial and corporate credits Newcastle Brown Ale commercial Droga 5 Arberia Roman Fort museum film Centre Screen Medical in house film Scenario Role Play NHS Stroke Awareness film Tyne Media Rally Car film Landau Reece Theatre credits include: Shortcuts Rosie Kellegher Live Theatre Cuckoo Jack Janet Nettleton No Limits