Carlisle Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob's Pillow Dance Festival 2018 Runs June 20-August 26 with 350+ Performances, Talks, Events, Exhibits, Classes & Works

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK FOR IMAGES AND MORE INFORMATION CONTACT: Nicole Tomasofsky, Public Relations and Publications Coordinator 413.243.9919 x132 [email protected] JACOB’S PILLOW DANCE FESTIVAL 2018 RUNS JUNE 20-AUGUST 26 WITH 350+ PERFORMANCES, TALKS, EVENTS, EXHIBITS, CLASSES & WORKSHOPS April 26, 2018 (Becket, MA)—Jacob’s Pillow announces the Festival 2018 complete schedule, encompassing over ten weeks packed with ticketed and free performances, pop-up performances, exhibits, talks, classes, films, and dance parties on its 220-acre site in the Berkshire Hills of Western Massachusetts. Jacob’s Pillow is the longest-running dance festival in the United States, a National Historic Landmark, and a National Meal of Arts recipient. Founded in 1933, the Pillow has recently added to its rich history by expanding into a year-round center for dance research and development. 2018 Season highlights include U.S. company debuts, world premieres, international artists, newly commissioned work, historic Festival connections, and the formal presentation of work developed through the organization’s growing residency program at the Pillow Lab. International artists will travel to Becket, Massachusetts, from Denmark, Israel, Belgium, Australia, France, Spain, and Scotland. Notably, representation from across the United States includes New York City, Minneapolis, Houston, Philadelphia, San Francisco, and Chicago, among others. “It has been such a thrill to invite artists to the Pillow Lab, welcome community members to our social dances, and have this sacred space for dance animated year-round. Now, we look forward to Festival 2018 where we invite audiences to experience the full spectrum of dance while delighting in the magical and historic place that is Jacob’s Pillow. -

Dance Department Consultants

Dance Department Consultants Lisa Alfieri Ballo Ms. Ballo - Consultant in Ballet - trained on full scholarship at the Pennsylvania Ballet under Lupe Serrano and at the San Francisco Ballet and Cleveland Ballet schools. Her professional career includes dancing with Sandra Organ Dance Company, Fort Worth- Dallas Ballet and prior to that with Cleveland - San Jose Ballet where she rose to principal dancer during her ten year stay. She has also danced as a principal guest artist nationally as well as internationally. As a teacher, she has taught in schools for the Cleveland Ballet, Ballet Arkansas, Twin City Ballet and the Houston Ballet Academy. Recently, she was Ballet Mistress for the Houston Repertoire Ballet's senior company and is currently teaching at the Hope Center. Lauren Bay Consultant in modern dance, ballet and tap dance. Ms. Perrone holds a BFA in Modern Dance Pedagogy from the University of Oklahoma where she studied with Mary Margaret Holt, Denise Vale and Austin Hartel. She is a 2000 HSPVA Dance graduate and a native Houstonian where she began her dance training with Paula Sloan and performed with The Texas Tap Ensemble. After college she also studied in New York City with Mark Morris, the Limon Dance Company, Nicole Wolcott, and Julian Barnett, among others. Her professional credits include: Houston Grand Opera's Aida; Galveston Island Musicals' My Fair Lady, America the Beautiful, and Hello Dolly. She has toured nationally as the dance captain of Mame and internationally to France and Paraguay with the Modern Repertory Dance Theater. Her New York City credits include the Jeff Rebudal Dance Company, Murray Hill Productions, and Lance Cruze Performance Group. -

The Limón Legacy Still Thrives After 70 Years by Jeff Slayton March 25, 2017

The Limón Legacy Still Thrives After 70 Years By Jeff Slayton March 25, 2017 The Limón Dance Company - Photo by Joseph Schembri “There is a dance for every single human experience.” José Limón The Limón Dance Company lit up the stage at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, presenting three works choreographed by José Limón over seventy years ago, and two recent works by Colin Connor and Kate Weare. Thanks to dance artists like Carla Maxwell, Risa Steinberg, Gary Masters and the new Artistic Director Colin Connor, the company has kept the Limón legacy alive and vibrant. In addition, the company continues to present new works by seasoned and up-and-coming choreographers. Born in Culiacan, Mexico, José Limón (1908-1972) formed his company in 1946 after performing for 10 years with modern dance pioneers Doris Humphrey and Charles Weidman. Throughout his life, Limón continued to create new works; his last one being Carlota in 1972, the year of his death. In 1997, this great dance master was inducted into the Hall of Fame at the National Museum of Dance in Saratoga Springs, NY. The program opened with Limón’s CONCERTO GROSSO which premiered in 1945 at the Humphrey-Weidman Studio in New York. Through his choreography, Limón artfully and brilliantly visualizes Antonio Vivaldi’s Concerto #11 in D Minor, Opus 3. The work is, simply put, pure and joyful dancing. Staged and directed by former company member Risa Steinberg, dancers Kathryn Alter, Elise Drew Leon and Jesse Obremski performed with great musicality, clarity and ease. CONCERTO GROSSO is a jewel and these three dance artists are wonderful in it. -

Cockerel, Pierrette in Harlequinade, Blanche Ingram in Jane Eyre

Founders Stella Abrera is the Artistic Director of Kaatsbaan and a Principal Dancer with American Ballet Gregory Cary Kevin McKenzie Theatre. Ms. Abrera is from South Pasadena, California, and began her studies with Philip and Bentley Roton Martine van Hamel Charles Fuller and Cynthia Young at Le Studio in Pasadena. She continued her studies with Lorna Executive Director Diamond and Patricia Hoffman at the West Coast Ballet Theatre in San Diego. She also spent three Sonja Kostich Artistic Director years studying the Royal Academy of Dancing method with Joan and Monica Halliday at the Stella Abrera Halliday Dance Centre in Sydney, Australia. Board of Trustees Kevin McKenzie, Chair Stella Abrera Ms. Abrera joined American Ballet Theatre as a member of the corps de ballet in 1996, was Christine Augustine Gregory Cary appointed a Soloist in 2001, and Principal Dancer in August 2015. Her repertoire with ABT includes Sandy Choi Sonja Kostich the Girl in Afternoon of a Faun, Calliope in Apollo, Gamzatti and a Shade in La Bayadère, The Chris Omark Bentley Roton Ballerina in The Bright Stream, Cinderella and Fairy Godmother in Frederick Ashton’s Cinderella, Martine van Hamel Moss and Cinderella in James Kudelka’s Cinderella, Aurora in Coppélia, Gulnare and an Odalisque Board of Advisors in Le Corsaire, Chloe in Daphnis and Chloe, She Wore a Perfume in Dim Lustre, the woman in white Dancers Isabella Boylston in Diversion of Angels, Mercedes, the Driad Queen and a Flower Girl in Don Quixote, Helena in The Gary Chryst Herman Cornejo Dream, the first -

Raising the Barre: the Geographic, Financial, and Economic Trends of Nonprofit Dance Companies

Raising the Barre: The Geographic, Financial, and Economic Trends of Nonprofit Dance Companies A Study by Thomas M. Smith Research Division Report #44 RESEARCH DIVISION REPORT #44 1 COVER PHOTO Hubbard Street Dance Chicago’s production of Jim Vincent’s counter/part. (Photo by Todd Rosenberg) Raising the Barre: The Geographic, Financial, and Economic Trends of Nonprofit Dance Companies A Study by Thomas M. Smith Foreword by Douglas C. Sonntag Edited by Bonnie Nichols Contributions by Janelle Ott and Don Ball Research Division Report #44 This report was produced by the National Endowment for the Arts Research Division Tom Bradshaw, Director Acknowledgements The NEA Research Division would like to thank Kelly Barsdate (National Assembly of State Arts Agencies), Thomas Pollak (National Center on Charitable Statistics), and John Munger (Dance/USA) for their contributions and counsel; and Stephanie Colman (former division assistant with the NEA Dance Department) for her database assistance. August 2003 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smith, Thomas M., 1969- Raising the barre: the geographic, financial, and economic trends of nonprofit dance companies: a study by Thomas M. Smith; foreword by Douglas C. Sonntag; edited by Bonnie Nichols; contributions by Janelle Ott and Don Ball. p. cm. -- (Research Division report; #44) 1. Dance companies--Economic aspects--United States. 2. Nonprofit organizations--Economic aspects--United States. 3. National Endowment for the Arts. I. Nichols, Bonnie. II. Ott, Janelle. III. Ball, Don, 1964- -

Nederlands Dans Theater Bambill

1994 NEXT WAVE FESTIVAL 1994 NEXT WAVE COVER AND POSTER ARTIST ROBERT MOSKOWITZ NEDERLANDS DANS THEATER BAMBILL BROOKLYN ACADEMY OF MUSIC Harvey Lichtenstein, President & Executive Producer presents in the BAM Opera House October 17, 1994, 7pm; October 18-22, 8pm and in the BAM Majestic Theater October 24-29, 8pm; October 30, 3pm NEIERLANIS IANS THEATER Artistic Director: JIRI KYLIAN Managing Director: MICHAEL DE Roo Choreographers: JIRI KYLIAN & HANS VAN MANEN Musical Director: CHRISTOF ESCHER Executive Artistic Directors: GLENN EDGERTON (NDT1), GERALD TIBBS (NDT2), ARLETTE VAN BOVEN (NDT3) Assistants to the Artistic Directors: HEDDA TWIEHAUS (NDT 2) & GERARD LEMAITRE (NDT 3) Rehearsal Assistant to the Rehearsal/Video Director Artistic Director Director ROSLYN ANDERSON ULF ESSER HANS KNILL Company Organization Musical Coordinator/ Manager (NDT 2) (NDT1&3) Pianist CARMEN THOMAS CARINA DE GOEDEREN RAYMOND LANGEWEN Guest Choreographers (1994/95 season) MAURICE BEJART CHRISTOPHER BRUCE MARTHA CLARKE PATRICK DELCROIX WILLIAM FORSYTHE LIONEL HoCtIE PAUL LIGHTFOOT JENNIFER MULLER OHAD NAHARIN GIDEON OBARZANEK PHILIPPE TREHET PATRIZIA TUERLINGS Guest Teachers BENJAMIN HARKARVY (Guest teacher, North American tour) CHRISTINE ANTHONY KATHY BENNETS JEAN-PIERRE BONNEFOUX OLGA EVREINOFF IVAN KRAMAR IRINA MILOVAN JAN NUYTS ALPHONSE POULIN LAWRENCE RHODES MARIAN SARSTADT Technical Director Marketing & Publicity Joop CABOORT KEES KORSMAN & EVELINE VERSLUIS Costume Department Tour Management JOKE VISSER WANDA CREMERS Pianist Dance Fitness Therapist Chiropractor -

Jacob's Pillow Announces Full Schedule of Virtual

NATIONAL MEDAL OF ARTS | NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK FOR MORE INFORMATION AND PHOTOS CONTACT: Nicole Tomasofsky, Interim Director of Marketing & Communications [email protected] JACOB’S PILLOW ANNOUNCES FULL SCHEDULE OF VIRTUAL FESTIVAL WITH A MODEL THAT SHARES DONATIONS FOR PERFORMANCES WITH ARTISTS July 1, 2020 (Becket, MA) —Jacob’s Pillow, home to the longest-running dance festival in the United States, launches a Virtual Festival with eight weeks of free programming, July 7-August 29. Weekly highlights feature streams of beloved Festival performances from the past ten years, a series of new PillowTalks with leaders in the dance field, an online version of the beloved intergenerational movement class Families Dance together, and a new Master Class Series from The School at Jacob’s Pillow. Attendees are encouraged to make a contribution in lieu of purchasing a ticket and fifty percent of donations for performances will be shared with the artists featured. Community Engagement events will share proceeds with local community organizations. “After we canceled our on-site Festival due to the global pandemic, we soon realized the need to fulfill our mission by engaging artists and audiences in a quintessential summer experience from Jacob’s Pillow virtually,” says Jacob’s Pillow Executive & Artistic Director Pamela Tatge. “The civic organizing and protests confronting racism and inequality in our country greatly impacts our organization’s decision-making. The model we envision is one that is free for all, made more accessible by being entirely online, pays artists and scholars for their time, and provides artists with additional support during a time when many have lost their income. -

Student Ballet 4 PLUS! This Link Contains All of the Information You Need to Register for 2016–2017 at Princeton Ballet School

301 North Harrison Street, Princeton, N.J. 08540 phone: (609)921-7758 fax: (609)921-3249 Photo: Horst Frankenberger Horst Photo: From the Director’s Desk Welcome to Student Ballet 4 PLUS! This link contains all of the information you need to register for 2016–2017 at Princeton Ballet School. Please be sure to read through each of these elements as you prepare to register; there is new information you will want to be aware of. Table of contents: • Student Ballet 4 PLUS information • Class schedule • Fees and registration information • Registration form • Student uniform order form (Giselle of Princeton) » Orders received after July 15 may not be available in time for the start of classes (more detailed information can be found on the order form) • Princeton Ballet School Handbook » Includes uniform requirements » Includes school calendar • Directions to our studios • Link to 2016 Summer Adult Open Enrollment brochure (located at the end of class schedules) • American Repertory Ballet Juniors audition (June 22) and membership information 301 North Harrison Street, Princeton, N.J. 08540 phone: (609)921-7758 fax: (609)921-3249 ARBW Junior Audition Information Dear dancer, If you’ve ever wondered how we get our thrilling productions up on the stage in such a way as to keep everyone talking about them for days; if you’ve ever wondered why people keep saying “it’s so professional”; if you’ve ever wondered how our dancers get this done — come and try for a chance to find out! We haven’t time to bask in the glow of our school show, Swan Lake: the American Repertory Ballet Workshop Juniors audition is just around the corner! We invite you to come audition for the opportunity to join this special group of dancers who comprise ARBW Jr, our entry level performing company. -

Grew up in New Jersey and Studied Ballet at a Young Age with the New Jersey Ballet School

Patricia Brown: grew up in New Jersey and studied ballet at a young age with the New Jersey Ballet School. As a teenager, Patricia was awarded full scholarships to the American Ballet Theatre School and the Joffrey Ballet School. Ms. Brown has danced professionally with the New Jersey Ballet Company, Joffrey II Ballet Company, Cleveland Ballet (soloist), the Elliot Feld Ballet, and the Joffrey Ballet Company (soloist). She has worked with many well-known choreographers such as Agnes DeMille, Anthony Tudor, Gerald Arpino, Elliot Feld, Paul Taylor, Laura Dean, and Dennis Nahat. Ms. Brown has served as principal teacher for trainee programs at the Milwaukee Ballet School, Joffrey Ballet School, Harrisburg Ballet School, Nashville Ballet School, The Dance Center, and the Mill Ballet School. She has taught company classes for Joffrey II Ballet, the Elliot Feld Ballet, Nashville Ballet, Harrisburg Ballet, Brandywine Ballet Theatre, the Roxey Ballet, and she has served as Ballet Mistress for the Pennsylvania Ballet. Ms. Brown has choreographed ballets performed at Joffrey Ballet workshop, Milwaukee Ballet workshop, Harrisburg Ballet Company, Brandywine Ballet Theater, the Roxey Ballet and for the international competition at Avery Fisher Hall in New York. Patricia has been asked to join the faculty of the Joffrey School in New York City and commutes weekly to teach class. Val Gontcharov: In 1974 at the age of 11 Val successfully competed against 40 other applicants for the one opening in the Kieu Ballet School. After graduation in 1982, five different companies offered him positions, but he chose the Donetsk Ballet to be closer to his parents' home. -

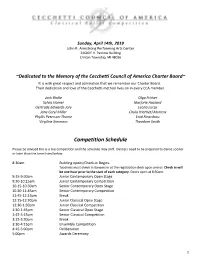

Competition Schedule

Sunday, April 14th, 2019 John R. Armstrong Performing Arts Center 24600 F.V. Pankow Building Clinton Township, MI 48036 ~Dedicated to the Memory of the Cecchetti Council of America Charter Board~ It is with great respect and admiration that we remember our Charter Board. Their dedication and love of the Cecchetti method lives on in every CCA member. Jack Bickle Olga Fricker Sylvia Hamer Marjorie Hassard Gertrude Edwards-Jory Leona Lucas Jane Caryl Miller Chula (Harriet) Morrow Phyllis Peterson-Thorne Enid Ricardeau Virgiline Simmons Theodore Smith Competition Schedule Please be advised this is a live competition and the schedule may shift. Dancers need to be prepared to dance sooner or later than the time listed below. 8:30am Building opens/Check-in Begins Teachers must check in dancers in at the registration desk upon arrival. Check in will be one hour prior to the start of each category. Doors open at 8:30am. 9:15-9:30am Junior Contemporary Open Stage 9:30-10:15am Junior Contemporary Competition 10:15-10:30am Senior Contemporary Open Stage 10:30-11:45am Senior Contemporary Competition 11:45-12:15pm Break 12:15-12:30pm Junior Classical Open Stage 12:30-1:30pm Junior Classical Competition 1:30-1:45pm Senior Classical Open Stage 1:45-3:15pm Senior Classical Competition 3:15-3:30pm Break 3:30-4:15pm Ensemble Competition 4:15-5:00pm Deliberation 5:00pm Awards Ceremony 1 Participating Studios Dear Participants, Parents and Teachers, Welcome to the first Cecchetti Classical Ballet Competition! We are thrilled that you are taking part in this competition and hope that you will learn from each other and the feedback that you receive. -

2.08 Summer Workshop PRINT

MARY BETH CABANA Founding Artistic Director MARY BETH CABANA, Founding Artistic Director, has been a Principal Dancer with In Cooperation with Cleveland Ballet, Ballet Oklahoma, Arizona Dance Theatre, and San Diego Ballet. She began her professional career at the age of 14 with Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre and graduated from the National The University of Arizona School of Dance Academy of Dance where she was a full scholarship student and member of the National Academy Ballet. She has performed extensively in the United States and has toured Europe performing in a wide variety of roles by such noted choreographers as Balanchine, Tudor, DeMille, Joos, Forsythe, Fokine, Petipa, and Nahat to name just a few. 29th Annual Ms. Cabana has been on the faculties of the School of Cleveland Ballet, Ballet Arts-Carnegie Hall, Dance Concepts-NYC and was the Principal Instructor and Administrator for Arizona Dance Theatre (Ballet Arizona). She has guest taught for Kiev Ukraine Ballet and Palace of Pioneers in SUMMER DANCE the former Soviet Union, in France and Mexico and continues to guest teach throughout the United States. She has also directed summer intensive programs for Ballet Pacifica in Irvine, California (under the direction of Ethan Stiefel). As a choreographer, she has produced numerous original works for Ballet Tucson and has staged dances for Arizona Opera Company, Arizona WORKSHOP 2014 Theatre Company, Yuma Ballet Theatre, Blue Lake Fine Arts Camp, Ohio Ballet, and Burklyn Ballet Theatre. Since beginning in 1986, she has been responsible for the establishment of four professional training institutions in Southern Arizona including studios in Tucson and Nogales and branch programs in Patagonia and Sierra Vista. -

University of Oklahoma Graduate College Second and Trainee Companies in the United States

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE SECOND AND TRAINEE COMPANIES IN THE UNITED STATES: AN ANALYSIS OF PAST AND PRESENT MISSIONS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF FINE ARTS IN DANCE By TYE ASHFORD LOVE Norman, Oklahoma 2016 SECOND AND TRAINEE COMPANIES IN THE UNITED STATES: AN ANALYSIS OF PAST AND PRESENT MISSIONS A THESIS APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF DANCE BY ______________________________ Mr. Jeremy Lindberg, Chair ______________________________ Mr. Ilya Kozadayev ______________________________ Mr. Robert Bailey © Copyright by TYE ASHFORD LOVE 2016 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I first want to thank my extraordinary committee members who without their inspiration in class and in life this document could not be possible, chair Jeremy Lindberg, as well as Ilya Kozadayev and Robert Bailey. I also want to thank the faculty of the University of Oklahoma School of Dance for their continuous support throughout my career, and valuable guidance from Dean Mary-Margaret Holt. I am also lucky to have the best family you could ask for, and their support is priceless. The phone call from home everyday is something I always look forward to. Thank you so much Mom and Dad! I also want to salute my amazing wife who is my biggest fan, thesis editor, best friend, and greatest love. I want to dedicate this document to my late mentor, John Magnus. John inspired many, including myself, to pursue a career in dance with his incredible passion and knowledge of guiding dancers. A passion I hope to pass down to future generations.