Glocester, RI Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Glocester Proposed Comprehensive Plan Amendment #20-01

TOWN OF GLOCESTER PROPOSED COMPREHENSIVE PLAN AMENDMENT #20-01 The Town is proposing a series of amendments to the existing Comprehensive Plan which was adopted on April 19, 2018. Amendments are proposed to the text of the following sections of the Comprehensive Plan: Goals, Policies, Actions and Implementation Program, Land Use, Natural, Historic and Cultural Resources, Open Space and Recreational Resources, Services and Facilities, Economic Development and Housing. This plan is being amended in accordance with the provisions of Chapter 45-22.2 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. FIRST READING approved by Glocester Town Council – September 4, 2020 PUBLIC HEARING is scheduled for October 1, 2020 at 7:30 A Joint Public Hearing will be held before the Glocester Town Council and the Glocester Planning Board at which the proposed Amendment #20-01 of the Glocester Comprehensive Plan and an amendment to Chapter 1. General Provisions, Article III Comprehensive Community Plan, of the Glocester Code of Ordinances will be considered. The public hearing shall be held on Thursday, October 1, 2020 at 7:30 p.m. Pursuant to R.I. Executive Order #20-05 executed by Governor Gina Raimondo, this meeting will be teleconferenced via Zoom: To Access the PUBLIC HEARING Via Computer: https://zoom.us/j/92985611295?pwd=ci9OalV1Ny85WG9wRzB3L3pWN204Zz09 Via Telephone: 833 548 0282 US Toll-free 877 853 5247 US Toll-free 888 788 0099 US Toll-free 833 548 0276 US Toll-free Meeting ID: 929 8561 1295 Meeting Password: 615550 The proposed Comprehensive Plan language may be altered or amended prior to the close of the public hearing without further advertising as a result of further study or because of the views expressed at the public hearing. -

RI Freshwater and Anadromous Fishing Regulations for the 2003-2004 Season

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FISH AND WILDLIFE Freshwater and Anadromous FISHING REGULATIONS for the 2003 - 2004 SEASON AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted pursuant to Chapter 20-1-4, 20-1-12 and 20-1-13, 42-17.1, 42-17.6 , and 42-35, “Administrative Procedures Act” of the General Laws of 1956, as amended. STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT FISH AND WILDLIFE RHODE ISLAND FISHING REGULATIONS for the 2003 - 2004 SEASON T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S RULE 1 Purpose .................................................................................................... iii RULE 2 Authority.................................................................................................... iii RULE 3 Application................................................................................................ iii RULE 4 Severability............................................................................................... iii RULE 5 Superseded Rules and Regulations..................................................... iii RULE 6 Regulations.............................................................................................1-6 PART I - FRESHWATER FISHERIES REGULATIONS ...................1 PART II - ANADROMOUS FISHERIES REGULATIONS ..................5 RULE 7 Effective Date............................................................................................7 FWFISHING.DEM (2003-2004) iii STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE -

Geological Survey

imiF.NT OF Tim BULLETIN UN ITKI) STATKS GEOLOGICAL SURVEY No. 115 A (lECKJKAPHIC DKTIOXARY OF KHODK ISLAM; WASHINGTON GOVKRNMKNT PRINTING OFF1OK 181)4 LIBRARY CATALOGUE SLIPS. i United States. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Department of the interior | | Bulletin | of the | United States | geological survey | no. 115 | [Seal of the department] | Washington | government printing office | 1894 Second title: United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Rhode Island | by | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] | Washington | government printing office 11894 8°. 31 pp. Gannett (Henry). United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | A | geographic dictionary | of | Khode Island | hy | Henry Gannett | [Vignette] Washington | government printing office | 1894 8°. 31 pp. [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (U. S. geological survey). Bulletin 115]. 8 United States geological survey | J. W. Powell, director | | * A | geographic dictionary | of | Ehode Island | by | Henry -| Gannett | [Vignette] | . g Washington | government printing office | 1894 JS 8°. 31pp. a* [UNITED STATES. Department of the interior. (Z7. S. geological survey). ~ . Bulletin 115]. ADVERTISEMENT. [Bulletin No. 115.] The publications of the United States Geological Survey are issued in accordance with the statute approved March 3, 1879, which declares that "The publications of the Geological Survey shall consist of the annual report of operations, geological and economic maps illustrating the resources and classification of the lands, and reports upon general and economic geology and paleontology. The annual report of operations of the Geological Survey shall accompany the annual report of the Secretary of the Interior. All special memoirs and reports of said Survey shall be issued in uniform quarto series if deemed necessary by tlie Director, but other wise in ordinary octavos. -

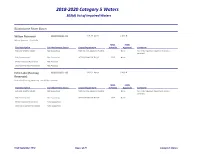

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(D) List of Impaired Waters

2018-2020 Category 5 Waters 303(d) List of Impaired Waters Blackstone River Basin Wilson Reservoir RI0001002L-01 109.31 Acres CLASS B Wilson Reservoir. Burrillville TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Secondary Contact Recreation Not Assessed Echo Lake (Pascoag RI0001002L-03 349.07 Acres CLASS B Reservoir) Echo Lake (Pascoag Reservoir). Burrillville, Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Draft September 2020 Page 1 of 79 Category 5 Waters Blackstone River Basin Smith & Sayles Reservoir RI0001002L-07 172.74 Acres CLASS B Smith & Sayles Reservoir. Glocester TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. Impairment is not a pollutant. Fish Consumption Not Supporting MERCURY IN FISH TISSUE 2025 None Primary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Secondary Contact Recreation Fully Supporting Slatersville Reservoir RI0001002L-09 218.87 Acres CLASS B Slatersville Reservoir. Burrillville, North Smithfield TMDL TMDL Use Description Use Attainment Status Cause/Impairment Schedule Approval Comment Fish and Wildlife habitat Not Supporting COPPER 2026 None Not Supporting LEAD 2026 None Not Supporting NON-NATIVE AQUATIC PLANTS None No TMDL required. -

RI DEM/Water Resources

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS July 2006 AUTHORITY: These regulations are adopted in accordance with Chapter 42-35 pursuant to Chapters 46-12 and 42-17.1 of the Rhode Island General Laws of 1956, as amended STATE OF RHODE ISLAND AND PROVIDENCE PLANTATIONS DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT Water Resources WATER QUALITY REGULATIONS TABLE OF CONTENTS RULE 1. PURPOSE............................................................................................................ 1 RULE 2. LEGAL AUTHORITY ........................................................................................ 1 RULE 3. SUPERSEDED RULES ...................................................................................... 1 RULE 4. LIBERAL APPLICATION ................................................................................. 1 RULE 5. SEVERABILITY................................................................................................. 1 RULE 6. APPLICATION OF THESE REGULATIONS .................................................. 2 RULE 7. DEFINITIONS....................................................................................................... 2 RULE 8. SURFACE WATER QUALITY STANDARDS............................................... 10 RULE 9. EFFECT OF ACTIVITIES ON WATER QUALITY STANDARDS .............. 23 RULE 10. PROCEDURE FOR DETERMINING ADDITIONAL REQUIREMENTS FOR EFFLUENT LIMITATIONS, TREATMENT AND PRETREATMENT........... 24 RULE 11. PROHIBITED -

Estimated Water Use and Availability in the Pawtucket and Quinebaug

Estimated Water Use and Availability in the Pawtuxet and Quinebaug River Basins, Rhode Island, 1995–99 By Emily C. Wild and Mark T. Nimiroski Prepared in cooperation with the Rhode Island Water Resources Board Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5154 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey P. Patrick Leahy, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2007 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Wild, E.C., and Nimiroski, M.T., 2007, Estimated water use and availability in the Pawtuxet and Quinebaug River Basins, Rhode Island, 1995–99: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2006–5154, 68 p. iii Contents Abstract . 1 Introduction . 2 Purpose and Scope . 2 Previous Investigations . 2 Climatological Setting . 6 The Pawtuxet River Basin . 6 Land Use . 7 Pawtuxet River Subbasins . 7 Minor Civil Divisions . 17 The Quinebaug River Basin . 20 Estimated Water Use . 20 New England Water-Use Data System . -

Dam Safety Program

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND 2009 Annual Report to the Governor on the Activities of the DAM SAFETY PROGRAM Overtopping earthen embankment of Creamer Dam (No. 742), Tiverton Department of Environmental Management Prepared by the Office of Compliance and Inspection TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY OF RHODE ISLAND’S DAM SAFETY PROGRAM....................................................................3 STATUTES................................................................................................................................................3 GOVERNOR’S TASK FORCE ON DAM SAFETY AND MAINTENANCE .................................................3 DAM SAFETY REGULATIONS .................................................................................................................4 DAM CLASSIFICATIONS..........................................................................................................................5 INSPECTION PROGRAM ............................................................................................................................7 ACTIVITIES IN 2009.....................................................................................................................................8 UNSAFE DAMS.........................................................................................................................................8 INSPECTIONS ........................................................................................................................................10 High Hazard Dam Inspections .............................................................................................................10 -

March 2020 Woodardcurran.Com 212683.31 COMMITMENT & INTEGRITY DRIVE RESULTS

2019 Annual Report Small Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System (MS4) Burrillville, RI March 2020 woodardcurran.com 212683.31 COMMITMENT & INTEGRITY DRIVE RESULTS MINIMUM CONTROL MEASURE #1: PUBLIC EDUCATION AND OUTREACH (Part IV.B.1 General Permit ) SECTION I. OVERALL EVALUATION: GENERAL SUMMARY, STATUS, APPROPRIATENESS AND EFFECTIVENESS OF MEASURABLE GOALS: Include information relevant to the implementation of each measurable goal, such as activities, topics addressed, audiences and pollutants targeted. Discuss activities to be carried out during the next reporting cycle. If addressing TMDL requirements, please indicate rationale for choosing the education activity to address the pollutant of concern. Responsible Party Contact Name & Title: _______________________________________________________________ Phone: DPW: (401) 568-4440 Em ail: Jeffrey McCormick, Director, [email protected] IT: (401) 568-4300, ext.129, 135 *Marc Maine, [email protected] Planning: (401) 568-4300, ext. 130, 131 *Nicole Stockwell, Deputy Planner [email protected] Ray Goff, Planning Director [email protected] Parks and Recreation: (401) 568-9470 Andrea Hall, Recreation Director, [email protected] IV.B.1.b.1 Use the space below to provide a General Summary of activities implemented to educate your community on how to reduce stormwater pollution. For TMDL affected areas, with stormwater associated pollutants of concern, indicate rationale for choosing the education activity. List materials used for public education and topics addressed. Summarize implementation status and discuss if the activity is appropriate and effective. The Town’s DPW website (https://www.burrillville.org/public-works) includes links to the webpages “Storm Water Management” and “Storm Drains”. The “Storm Water Management” webpage contains content describing what stormwater management is, the regulatory framework for stormwater management in RI, and the six control measures the Town implements through the Stormwater Management Plan (SWMP). -

Comprehensive Plan Is a Document That Sets the Vision of the Community by Outlining Long Range Goals and Accompanying Policies and Actions to Achieve Them

GLOCESTER 2040 Comprehensive Community Plan Amendment 20-01 Town Council and Planning Board Adoption – October 1, 2020 Effective Date – October 1, 2020 State Approval – July 25, 2018 Effective Date – May 3, 2018 Town Council Adoption – April 19, 2018 Planning Board Adoption – February 12, 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS PLANNING BOARD TOWN COUNCIL George R. Charette, Chair George O. Steere, Jr., President David Calderara, Vice-Chair Edward C. Burlingame, Vice President Michael DeGrange Patricia Henry Douglas Folcarelli William E. Reichert Lynne Furney Walter M.O. Steere, III Russell K. Gross Janine Pitocco TOWN PLANNER TOWN CLERK Karen G. Scott Jean M. Fecteau GIS ANALYST TOWN HISTORIAN Heidi Blank Edna M. Kent 2018 Plan language completed by Karen Scott, Town Planner. Mapping completed by Heidi Blank, GIS Analyst. Additional contributors include: Tim Ianacio, Former Town Planner for initial drafting efforts and Shamoon Planning LLC. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTERS 1. Introduction…………………………………………………………………………. 7 a. Development History b. The Statewide Setting c. Plan Background 2. A Twenty Year Vision for Glocester……………………………………….. 11 3. Goals, Policies, Actions & Implementation Program………………. 12 a. Land Use b. Natural, Historic and Cultural Resources c. Open Space and Recreational Resources d. Transportation e. Services and Facilities f. Economic Development g. Natural Hazards and Climate Change h. Housing 4. Demographic Profile……………………………………………………………… 27 5. Land Use……………………………………………………………………………….. 30 a. Existing Conditions b. Existing Zoning c. Land Capacity Analysis d. Future Land Use 6. Natural, Historic and Cultural Resources……………………………….. 40 a. Natural Resources i. Water Resources ii. Surface Water iii. Groundwater iv. Wetlands v. Floodplains vi. Habitat Assets vii. Shady Oak Brook Tree Farm viii. Threats to Natural Resources b. -

State of Rhode Island

STATE OF RHODE ISLAND 2001 Annual Report to the Governor on the Activities of the DAM SAFETY PROGRAM Dam No. 161 - Spillway at Gainer Memorial Dam, Scituate Department of Environmental Management Prepared by the Office of Compliance and Inspection TABLE OF CONTENTS HISTORY OF RHODE ISLAND’S DAM SAFETY PROGRAM....................................................................1 DAM CLASSIFICATIONS......................................................................................................................................1 STATUTES ..............................................................................................................................................................2 GOVERNOR’S TASK FORCE ON DAM SAFETY AND MAINTENANCE.....................................................2 PROFESSIONAL ASSOCIATIONS .............................................................................................................4 INSPECTION PROGRAM ............................................................................................................................4 ACTIVITIES IN 2001.....................................................................................................................................5 HIGH HAZARD DAM INSPECTIONS..................................................................................................................5 SIGNIFICANT HAZARD DAM INSPECTIONS ..................................................................................................6 LOW HAZARD DAM INSPECTIONS...................................................................................................................8 -

Onsite Wastewater Management Plan

I. INTRODUCTION An Onsite Wastewater Management Plan (OWMP) is a What is an Onsite Wastewater toolbox of strategies designed to ensure the proper design, Management Plan? location, construction, function and maintenance of onsite wastewater treatment systems. In RI onsite wastewater treatment systems are commonly referred to as ISDS and include both septic systems and cesspools. When properly developed and implemented an OWMP can help preserve and improve the quality of valuable ground and surface water resources, and provide a cost-effective alternative to municipal sewers. The Foster/Scituate OWMP contains the following principal components: 1. Public outreach, education and technical assistance plan. 2. A septic system inspection and maintenance program.1 3. Summary of zoning and subdivision provisions related to septic system setbacks and performance standards. 4. A financial incentive program for the repair and upgrade of failing and substandard systems. This OWMP also describes the nature of the problem, the impact of failed septic systems on ground and surface water and analyzes the causes of system failures. Furthermore, the Plan discusses the projected costs associated with the implementation of the OWMP and provides an environmental and economic perspective on the use of septic systems. The Scituate Reservoir Watershed Management Plan2 and the Comprehensive Plan of each town support the development of the Foster/Scituate Onsite Wastewater Management Plan. There are two main reasons to develop an OWMP. First, such a Why Develop an plan and accompanying ordinance and/or education program is OWMP? designed to protect ground and surface waters by preventing pollution from failing and sub-standard septic systems. -

Streamflow, Water Quality, and Constituent Loads and Yields, Scituate Reservoir Drainage Area, Rhode Island, Water Year 2004

Prepared in cooperation with the Providence Water Supply Board and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Streamflow, Water Quality, and Constituent Loads and Yields, Scituate Reservoir Drainage Area, Rhode Island, Water Year 2004 Open-File Report 2010–1044 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover. Photograph shows Peaptoad Brook. Streamflow, Water Quality, and Constituent Loads and Yields, Scituate Reservoir Drainage Area, Rhode Island, Water Year 2004 By Robert F. Breault and Jean P. Campbell Prepared in cooperation with the Providence Water Supply Board and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management Open-File Report 2010–1044 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2010 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. Suggested citation: Breault, R.F., and Campbell, J.P., 2010, Streamflow, water quality, and constituent loads and yields, Scituate Reservoir drainage area, Rhode Island, water year 2004: U.S.