As Waterfront Land Dries Up, Developers Rush to Miami River

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

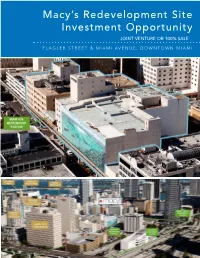

Macy's Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity

Macy’s Redevelopment Site Investment Opportunity JOINT VENTURE OR 100% SALE FLAGLER STREET & MIAMI AVENUE, DOWNTOWN MIAMI CLAUDE PEPPER FEDERAL BUILDING TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 3 PROPERTY DESCRIPTION 13 CENTRAL BUSINESS DISTRICT OVERVIEW 24 MARKET OVERVIEW 42 ZONING AND DEVELOPMENT 57 DEVELOPMENT SCENARIO 64 FINANCIAL OVERVIEW 68 LEASE ABSTRACT 71 FOR MORE INFORMATION, CONTACT: PRIMARY CONTACT: ADDITIONAL CONTACT: JOHN F. BELL MARIANO PEREZ Managing Director Senior Associate [email protected] [email protected] Direct: 305.808.7820 Direct: 305.808.7314 Cell: 305.798.7438 Cell: 305.542.2700 100 SE 2ND STREET, SUITE 3100 MIAMI, FLORIDA 33131 305.961.2223 www.transwestern.com/miami NO WARRANTY OR REPRESENTATION, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, IS MADE AS TO THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN, AND SAME IS SUBMITTED SUBJECT TO OMISSIONS, CHANGE OF PRICE, RENTAL OR OTHER CONDITION, WITHOUT NOTICE, AND TO ANY LISTING CONDITIONS, IMPOSED BY THE OWNER. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY MACY’S SITE MIAMI, FLORIDA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Downtown Miami CBD Redevelopment Opportunity - JV or 100% Sale Residential/Office/Hotel /Retail Development Allowed POTENTIAL FOR UNIT SALES IN EXCESS OF $985 MILLION The Macy’s Site represents 1.79 acres of prime development MACY’S PROJECT land situated on two parcels located at the Main and Main Price Unpriced center of Downtown Miami, the intersection of Flagler Street 22 E. Flagler St. 332,920 SF and Miami Avenue. Macy’s currently has a store on the site, Size encompassing 522,965 square feet of commercial space at 8 W. Flagler St. 189,945 SF 8 West Flagler Street (“West Building”) and 22 East Flagler Total Project 522,865 SF Street (“Store Building”) that are collectively referred to as the 22 E. -

Views the Miami Downtown Lifestyle Has Evolved

LOFT LIVINGwww.miamicondoinvestments.com REDESIGNED Feel the Street. At Your Feet. Out your window. At your feet. www.miamicondoinvestments.com ORAL REPRESENTATIONS CANNOT BE RELIED UPON AS CORRECTLY STATING THE REPRESENTATIONS OF THE DEVELOPER. FOR CORRECT REPRESENTATIONS, MAKE REFERENCE TO THIS BROCHURE AND TO THE DOCUMENTS REQUIRED BY SECTION 718.503, FLORIDA STATUTES, TO BE FURNISHED BY A DEVELOPER TO A BUYER OR LESSEE. OBTAIN THE PROPERTY REPORT REQUIRED BY FEDERAL LAW AND READ IT BEFORE SIGNING ANYTHING. NO FEDERAL AGENCY HAS JUDGED THE MERITS OR VALUE, IF ANY, OF THIS PROPERTY. See Legal Disclaimers on Back Cover. See Legal Disclaimers on Back Cover. www.miamicondoinvestments.com See Legal Disclaimers on Back Cover. Welcome to the Core of Downtown Life. www.miamicondoinvestments.com See Legal Disclaimers on Back Cover. See Legal Disclaimers on Back Cover. At the center of all life is a place from which all energy flows. In the heart of downtown Miami’s cultural and This is the fusion of commercial district, this is Centro - the new urban address inspired by today’s modern lifestyles. Smart and sleek... Lofty and livable... Inviting and exclusive... work, play, creativity, the Centro experience takes cosmopolitan city dwelling to street level. and accessibility. Step inside. www.miamicondoinvestments.com www.miamicondoinvestments.com See Legal Disclaimers on Back Cover. See Legal Disclaimers on Back Cover. Centro stands as proof that you truly can have it all. Location, style, quality, and value are all hallmarks of life Building Amenities Comfort. in our city center. • Triple-height lobby entrance • 24-Hour reception desk Step outside your door and find yourself in Miami’s • Secured key-fob entry access Convenience. -

Miami Office Space Can Be Found by Those Who Search February 7, 2017 By: Carla Vianna

Miami Office Space Can Be Found by Those Who Search February 7, 2017 By: Carla Vianna Businesses searching for space in Miami's urban core have more options than they might think. While vacancy rates are down across the board, significant chunks of space are available in several Class A buildings in downtown and the Brickell Avenue financial district. "There are more alternatives available for those companies that take the time to appropriately investigate the market," said Chris Lovell, a senior managing director with Savills Studley in Miami. Leasing space on an upper floor with a view may be difficult since only six buildings on Brickell have a full floor above the 20th story available for lease. For tenants that can live without the view, there is plenty of open space to choose from. Four downtown Class A buildings have at least 75,000 square feet of contiguous space available, one Class A building on Brickell has a 65,000- square-foot block — "and we don't have tenants of that size standing in line to the claim the space," Lovell said. Savills Studley has found many of the large available blocks are in older downtown buildings. "You're always going to have buildings that are going to have certain pockets available," said Tere Blanca, founder of Miami-based Blanca Commercial Real Estate Inc. She said the market is responding well to the new Miami Central project, which is under construction with 60 percent of its office component pre- leased. The mixed-use development will serve as Brightline's downtown train station and will add 286,000 square feet of office space in two buildings. -

Miami Condos Most at Risk Sea Level Rise

MIAMI CONDOS MIAMI CONDOS MOST AT RISK www.emiami.condos SEA LEVEL RISE RED ZONE 2’ 3’ 4’ Miami Beach Miami Beach Miami Beach Venetian Isle Apartments - Venetian Isle Apartments - Venetian Isle Apartments - Island Terrace Condominium - Island Terrace Condominium - Island Terrace Condominium - Costa Brava Condominium - -Costa Brava Condominium - -Costa Brava Condominium - Alton Park Condo - Alton Park Condo - Alton Park Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Mirador 1000 Condo - Floridian Condominiums - Floridian Condominiums - Floridian Condominiums - South Beach Bayside Condominium - South Beach Bayside Condominium - South Beach Bayside Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - Portugal Tower Condominium - La Tour Condominium - La Tour Condominium - La Tour Condominium - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Sunset Beach Condominiums - Tower 41 Condominium - Tower 41 Condominium - Tower 41 Condominium - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Eden Roc Miami Beach - Mimosa Condominium - Mimosa Condominium - Mimosa Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Carriage Club Condominium - Marlborough House - Marlborough House - Marlborough House - Grandview - Grandview - Grandview - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Monte Carlo Miami Beach - Sherry Frontenac - Sherry Frontenac - Sherry Frontenac - Carillon - Carillon - Carillon - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Ritz Carlton Bal Harbour - Harbor House - Harbor House -

Vice 300 Biscayne Boulevard

DOWNTOWN MIAMI FL VICE 300 BISCAYNE BOULEVARD CONCEPTUAL RENDERING SPACE DETAILS LOCATION GROUND FLOOR West block of Biscayne Boulevard between NE 3rd and NE 4th Streets NE 4TH STREET 38 FT SPACE Ground Floor 1,082 SF FRONTAGE 38 FT on NE 4th Street 1,082 SF TERM Negotiable (COMING SOON) POSSESION LEASE OUT Summer 2018 SITE STATUS New construction LEASE OUT CO-TENANTS Caffe Fiorino (coming soon), GOGO Fresh Foods (coming soon) and OXXO Care Cleaners (coming soon) NEIGHBORS Area 31, Fratelli Milano, CVI.CHE 105, Gap, Il Gabbiano, Juan Valdez Coffee, NIU Kitchen, Pollos & Jarras, Segafredo, Skechers, Starbucks, STK Miami, Subway, Ten Fruits, Toro Toro, Tuyo Restaurant, Victoria’s Secret, Wolfgang’s Steakhouse and Zuma COMMENTS VICE is a 464-unit apartment tower under construction in the heart of Downtown Miami Directly across from Bayside Marketplace and neighboring Miami Dade College, two blocks from American Airlines Arena, and adjacent to the College-Bayside Metromover Station Miami-Dade College has over 25,000 students on campus daily (COMING SOON) (COMING SOON) ADDITIONAL RENDERINGS CONCEPTUAL RENDERING CONCEPTUAL RENDERING CONCEPTUAL RENDERING Downtown Miami & Brickell Miami, FL AREASeptember 2017 RETAIL NW 8TH STREET NE 8TH STREET VICE AVENUE 300 BISCAYNE NE 7TH STREET NE 2ND HEAT BOULEVARD BOULEVARD MIAMI FL FREEDOM TOWER NW 6TH STREET PORT BOULEVARD MIAMI-DADE COLLEGE FACULTY Downtown Miami PARKING Movers NW 5TH STREET NE 5TH STREET 300 BISCAYNE BOULEVARDP MIAMI-DADE COLLEGE FEDERAL NE 4TH STREET NE -

Welcome to Kaplan Medical

Welcome to Kaplan Medical 4425 Ponce De Leon, #1612 Coral Gables, FL 33146 Miami Kaplan Center 4425 Ponce De Leon Boulevard Suite 1612 Coral Gables, FL 33146 Hours of Operation Monday-Thursday 9am - 9pm Friday-Sunday 10am - 5pm (305) 441-5323, Ext. 5000 or 5002 2 Our Neighborhood Coral Gables: Coral Gables’ founders imagined both a “City Beautiful” and a “Garden City,” with lush green avenues winding through a residential city, punctuated by civic landmarks and embellished with detailed and playful architectural features. Known as The City Beautiful, Coral Gables stands out as a planned community that blends color, details, and the Mediterranean Revival architectural style. International: From its inception, Coral Gables was designed to be an international City, and is now home to more than 20 consulates and foreign government offices and more than 140 multinational corporations. As early as 1925, City Founder George Merrick predicted Coral Gables would serve as "a gateway to Latin America." To further establish international ties, the City has forged relationships with six Sister Cities: Aix-en Provence, France; Cartagena, Colombia; Granada, Spain; La Antigua, Guatemala; Province of Pisa, Italy; and Quito, Ecuador (emeritus). 3 Our Neighborhood University of Miami: The University of Miami is located in Coral Gables Shopping: Coral Gables attracts national and regional retailers along with an abundance of boutiques and retail shops. Miracle Mile is the center of a true downtown district. Located across the street from the Kaplan Medical Center in Coral Gables is “The Village of Merrick Park”, a 780,000 square foot retail, residential and office project anchored by Neiman Marcus and Nordstrom, and has more than 100 other select retailers including Tiffany & Co., Burberry, Coach and Gucci. -

Met 1 Miami Brochure

m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a nm e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a n m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a nm e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a n m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a nm e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t ropolitan miami m e t r o p o l i t a n heads up, downtown! the renaissance of miami’s oldest neighborhood is on the move. -

Miami River Residential Development Projects

Miami River Residential Development Projects May 2009 **************************************************** The following “Miami River Residential Development Project List” is a reflection of riverfront properties that have either a) completed construction; b) commenced construction; or c) currently undergoing permitting and/or design phase since 2000. The following data was compiled by MRC staff based on information provided by developers, architects and a variety of sources associated with each distinct project. Please note projects are listed geographically from east to west. 1) Project Name: One Miami Location: 205 South Biscayne Boulevard, north bank of Miami River and Biscayne Bay Contact: Sales Office (305) 373-3737, 325 South Biscayne Boulevard Developer: The Related Group (305) 460-9900 Architect: Arquitectonica, Bernardo Fort-Brescia (305) 372-1812 Description: Twin 45-story residential towers with parking, connected to a new $4.1 million publicly accessible Riverwalk on the north shore trailhead Units: 896, one, two and three bedroom residences Website: www.relatedgroup.com/Our-Properties/past_projects.aspx Status: Construction completed in 2005 2) Project Name: Courts Brickell Key Location: 801 Brickell Key Boulevard Contact: Homeowners Association (305) 416-5120 Developer: Swire Properties (305) 371-3877 Description: 34 stories connected to a publicly accessible riverwalk Units: 319 condominium apartments Status: Construction completed in January 2003 3) Project Name: Carbonell Location: 901 Brickell Key Boulevard Contact: Homeowners Association (305) 371-4242 Developer Swire Properties (305) 371-3877 Description: 40 stories Units: 284 residential units Architect: J. Scott Architecture (305) 375-9388 Status: completed in October 2005 4) Project Name: Asia Location: 900 Brickell Key Drive Contact: Megan Kelly (305) 371-3877 Developer: Swire Properties (305) 371-3877 Description: 36 stories connected to a publicly accessible riverwalk Units: 123 residential units Architect: J. -

Housing & Relocation Guide

HOUSING & RELOCATION GUIDE 2013-2014 2017- 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction p. 2 Helpful Resources p. 3 Real Estate Agents p. 4 Tips for a Successful Search p. 5 Tips for Avoiding Scams and Foreclosed Properties p. 5 Tips for Managing Your Budget p. 6 Tips for Finding a Roommate p. 6 Tips for Getting Around pp. 7 - 8 Popular Neighborhoods & Zip Codes pp. 9 - 10 Apartment & Condo Listings pp. 11 - 20 Map of Miami pp. 21 - 22 INTRODUCTION Welcome to the University of Miami School of Law Housing & Relocation Guide! Moving to a new city or a big city like Miami may seem daunting, but this Guide will make your transition into Miami Law a smooth one. The Office of Student Recruitment has published this Guide to help orient incoming students to their new city. The information provided in this publication has been gathered from numer- ous sources, including surveys completed by current law students. This information is compiled for your convenience but is by no means exhaustive. We are not affiliated with, nor do we endorse any property, organization or real estate agent/office listed in the Guide. Features listed are provided by the property agents. We strongly suggest you call in advance to schedule an appointment or gather more information, before visiting the properties. Please note that most rental prices and facilities have been updated for 2017, but the properties reserve the right to adjust rates at any time. Once you have selected an area to live in, it is wise to examine several possibilities to compare prices and quality. -

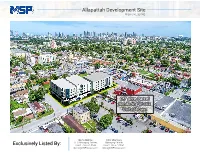

Allapattah Development Site Exclusively Listed

Allapattah Development Site Miami, FL 33142 0.7 Acre Parcel Rendering of 102 Units Shown Deme Mekras Elliot Shainberg CEO, Managing Partner Managing Partner Exclusively Listed By: Direct: 786.671.0149 Direct: 786.671.0151 [email protected] [email protected] Allapattah Development Site | 2137 NW 36th Street Table of Contents Confidentiality Disclaimer Property Description................................................................................ 3 This is a confidential Offering Memorandum intended solely for your limited use and benefit in de-termining whether you desire to express further interest into the acquisition of the Subject Property. This Offering Memorandum contains selected information pertaining to the Property Financial Analysis.................................................................................... 17 and does not purport to be a representation of state of affairs of the Owner or the Property, to be all-inclusive or to contain all or part of the information which prospective investors may Land Sales Comparables......................................................................... 21 require to evaluate a pur-chase of real property. All financial projections and information are provided for general reference purposes only and are based on assumptions relating to the general economy, market conditions, competition, and other factors beyond the control of Rent Comparables................................................................................... 25 the Owner or MSP Group ,LLC. Therefore, all projections, -

WAGNER CREEK and SEYBOLD CANAL RESTORATION PROJECT Project Number: B-50643 PUBLIC MEETING - SECTION 3 - 4

WAGNER CREEK AND SEYBOLD CANAL RESTORATION PROJECT Project Number: B-50643 PUBLIC MEETING - SECTION 3 - 4 MEETING SUMMARY DATE: Thursday September 21, 2017 TIME: 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. LOCATION: Miami Association of Fire Fighters - IAFF Local 587 ADDRESS: 2980 NW South River Drive Miami, Florida 33125 A. ATTENDANCE Elected Officials NAME TITLE 1 None City of Miami NAME TITLE 1 Jose Lago, PE Senior Project Manager 2 Robert Fenton Construction Manager Sevenson NAME TITLE 1 Jamie Fisher Construction Manager CH2M NAME TITLE 1 George Hicks Geologist, Senior Technical Consultant AECOM NAME TITLE 1 Jenn L. King, PE Sr. Project Manager/Public Involvement Officer 2 Babu Madabhushi, Sr. Project Manager, PE Environment 3 Dan Levy, PG Project Manager 4 Carolina de la Hoz Public Involvement 5 Mike Powell Public Involvement 6 Amparo Vargas Public Involvement Page 1 of 2 WAGNER CREEK AND SEYBOLD CANAL RESTORATION PROJECT Project Number: B-50643 PUBLIC MEETING - SECTION 3 - 4 MEETING SUMMARY DATE: Thursday September 21, 2017 TIME: 6:00 to 8:00 p.m. LOCATION: Miami Association of Fire Fighters - IAFF Local 587 ADDRESS: 2980 NW South River Drive Miami, Florida 33125 General Public NAME ORGANIZATION 1 Josh Trifiletti Spring Garden Resident 2 Pat Gajardo President, Allapattah Neighborhood Association 3 Rick Veber Spring Garden Civic Association B. PUBLIC COMMENTS NAME ORGANIZATION COMMENTS 1 Josh Trifiletti Spring Garden ▫ Lives on the Miami River resident ▫ Discussed Section 6 schedule and contents of the sediments ▫ Requested an email copy of the overview board and the project schedule ▫ Requested inclusion in all future notifications 2 Pat Gajardo President, Allapattah ▫ He is pleased with the project overall. -

10-00719 Exhibit SUB.Pdf

1 c` e ^krn `mac^^l ci•'Jk-Id6'-- ECONOMIC STIMULUS Expedite Legislation Attachment "A" - 6/24/10 (REVISED) Project#' Name Actions CONSTRUCTION (includes design-build] B-30514 North Bayshore Drive Operational Improvements B-40643A North Spring Garden Greenway Improvements B-30634A Brickell Key Bridge- removed - project awarded B-78508A ega^er^t @a removed - project awarded B-785086 - - - removed - project awarded B-40686 Miami River Greenway East Little Havana B-35883A Hadley Park Youth Center & Field Improvements B-35887 Moore Park Master Plan and New Building N/A removed- to be presented to City Commission for approval N/A Energy Efficient Retrofits B-35865A Coral Gate Community Center t3 75901A '- -: •' _-' :'•: removed - project awarded -306g4 nn ' '•:.•: ^- : _e •: • ! _! removed - project awarded B-30675 Biscayne Skate Park B-35002 Virginia Key Environmental Remediation B-30394 North 14th St. Entertainment District Streetscape Project B-30538A Large Vessel Mooring Facility B-30014 Northwest Road and Storm Sewer Improvements B-30008 Grove Park Road and Storm Sewer Improvements B-30681A CDBG Roadway Milling and Resurfacing Phase II revised - B# revised B-30011 Englewood Road and Storm Sewer Improvements B-30629 Durham Terrace Drainage Project B-30566A Melreese Golf Training Center B-30626 Omni Area Utility Improvements B-30035A North Shorecrest Road Improvements B-35806 Curtis Park New Pool Facility added - upcoming solicitation B-35853A Virrick Park New Pool Facility added - upcoming solicitation B-60453A Fire Station #13 added –upcoming solicitation B-30194A Manuel Artime ADA Improvements added - upcoming solicitation B-30579 Old Fire Station No. 2 Restoration added - upcoming solicitation B-30031A SW 3rd Avenue Road Improvements Project added - upcoming solicitation B-30588 San Marco & Biscayne Islands Drainage Improvements added - upcoming solicitation B-30130 Miami River Greenway SW 1st Court to S.