Lost Architecture of the East Frontier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catalogue of Exporters of Primorsky Krai № ITN/TIN Company Name Address OKVED Code Kind of Activity Country of Export 1 254308

Catalogue of exporters of Primorsky krai № ITN/TIN Company name Address OKVED Code Kind of activity Country of export 690002, Primorsky KRAI, 1 2543082433 KOR GROUP LLC CITY VLADIVOSTOK, PR-T OKVED:51.38 Wholesale of other food products Vietnam OSTRYAKOVA 5G, OF. 94 690001, PRIMORSKY KRAI, 2 2536266550 LLC "SEIKO" VLADIVOSTOK, STR. OKVED:51.7 Other ratailing China TUNGUS, 17, K.1 690003, PRIMORSKY KRAI, VLADIVOSTOK, 3 2531010610 LLC "FORTUNA" OKVED: 46.9 Wholesale trade in specialized stores China STREET UPPERPORTOVA, 38- 101 690003, Primorsky Krai, Vladivostok, Other activities auxiliary related to 4 2540172745 TEK ALVADIS LLC OKVED: 52.29 Panama Verkhneportovaya street, 38, office transportation 301 p-303 p 690088, PRIMORSKY KRAI, Wholesale trade of cars and light 5 2537074970 AVTOTRADING LLC Vladivostok, Zhigura, 46 OKVED: 45.11.1 USA motor vehicles 9KV JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 690091, Primorsky KRAI, Processing and preserving of fish and 6 2504001293 HOLDING COMPANY " Vladivostok, Pologaya Street, 53, OKVED:15.2 China seafood DALMOREPRODUKT " office 308 JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 692760, Primorsky Krai, Non-scheduled air freight 7 2502018358 OKVED:62.20.2 Moldova "AVIALIFT VLADIVOSTOK" CITYARTEM, MKR-N ORBIT, 4 transport 690039, PRIMORSKY KRAI JOINT-STOCK COMPANY 8 2543127290 VLADIVOSTOK, 16A-19 KIROV OKVED:27.42 Aluminum production Japan "ANKUVER" STR. 692760, EDGE OF PRIMORSKY Activities of catering establishments KRAI, for other types of catering JOINT-STOCK COMPANY CITYARTEM, STR. VLADIMIR 9 2502040579 "AEROMAR-ДВ" SAIBEL, 41 OKVED:56.29 China Production of bread and pastry, cakes 690014, Primorsky Krai, and pastries short-term storage JOINT-STOCK COMPANY VLADIVOSTOK, STR. PEOPLE 10 2504001550 "VLADHLEB" AVENUE 29 OKVED:10.71 China JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " MINING- METALLURGICAL 692446, PRIMORSKY KRAI COMPLEX DALNEGORSK AVENUE 50 Mining and processing of lead-zinc 11 2505008358 " DALPOLIMETALL " SUMMER OCTOBER 93 OKVED:07.29.5 ore Republic of Korea 692183, PRIMORSKY KRAI KRAI, KRASNOARMEYSKIY DISTRICT, JOINT-STOCK COMPANY " P. -

Final Report ______January 01 –December 31, 2003

Phoenix Final Report ____________________________________________________________________________________ January 01 –December 31, 2003 FINAL REPORT January 01 – December 31, 2003 The Grantor: Save the Tiger Fund Project No: № 2002 – 0301 – 034 Project Name: “Operation Amba Siberian Tiger Protection – III” The Grantee: The Phoenix Fund Report Period: January 01 – December 31, 2003 Project Period: January 01 – December 31, 2003 The objective of this project is to conserve endangered wildlife in the Russian Far East and ensure long-term survival of the Siberian tiger and its prey species through anti-poaching activities of Inspection Tiger and non-governmental investigation teams, human-tiger conflict resolution and environmental education. To achieve effective results in anti-poaching activity Phoenix encourage the work of both governmental and public rangers. I. KHABAROVSKY AND SPECIAL EMERGENCY RESPONSE TEAMS OF INSPECTION TIGER This report will highlight the work and outputs of Khabarovsky anti-poaching team and Special Emergency Response team that cover the south of Khabarovsky region and the whole territory of Primorsky region. For the reported period, the Khabarovsky team has documented 47 cases of ecological violations; Special Emergency Response team has registered 25 conflict tiger cases. Tables 1 and 2 show the results of both teams. Conflict Tiger Cases The Special Emergency Response Team works on the territory of Primorsky region and south of Khabarovsky region. For the reported period, 25 conflict tiger cases have been registered and investigated by the Special Emergency Response team of Inspection Tiger, one of them transpired to be a “false alarm”. 1) On January 04, 2003 the Special Emergency Response team received information from gas filling station workers that in the vicinity of Terney village they had seen a tiger with a killed dog crossing Terney-Plastun route. -

Subterranean Fauna from Siberia and Russian Far East ______ENCYCLOPAEDIA BIOSPEOLOGICA (Siberia-Far East Special Issue)

Research Article ISSN 2336-9744 (online) | ISSN 2337-0173 (print) The journal is available on line at www.biotaxa.org/em Subterranean fauna from Siberia and Russian Far East _________________ ENCYCLOPAEDIA BIOSPEOLOGICA (Siberia-Far East special Issue) CHRISTIAN JUBERTHIE1, DIMITRI SIDOROV2, VASILE DECU3, ELENA MIKHALJOVA2 & KSENIA SEMENCHENKO2 1Encyclopédie Biospéologique, Edition. 1 Impasse Saint-Jacques, 09190 Saint-Lizier France; e-mail: [email protected] 2Institute of Biology and Soil Science, 100-letiya Vladisvostoka Av. 159, 690022 Vladivostok, Russia; e-mail: [email protected] 3Institutul de Speologie "Emil Racovitza", Academia romana, Calea 13 Septembrie, 13050711 Bucarest, Roumanie Received 20 March 2016 │ Accepted 25 November 2016 │ Published online 29 November 2016. Abstract Description of the main karstic regions of Siberia and Far East, and the most important caves. Survey of the subterranean species collected in caves, springs, hyporheic and MSSh. Relationship with the climate and glacial paleoclimatic periods to explain the paucity of the terrestrial fauna of Siberia. Persistence of some aquatic stygobionts (Crustacea), and richness of the subterranean fauna of the Far East, particularily in the Sikhote-Alin. The Crutaceans of the eastern part of the Ussury basin and Sakhalin Island have relationship with the Japanese and Korean fauna. Key words: karst, caves, springs, MSS, subterranean fauna, biogeography. 1 Generalities and History The study of caves in Siberia was begun in the late 17th century (Tsykin et al., 1979), but the first published report were made as early as in the 18th century by swedish geographer P. von Strahlenberg who in 1722 visited the cave on the Yenisei river bank above Krasnoyarsk and gave a short description, which is considered the first report of caves in Siberia (Strahlenberg, 1730). -

Ricken and Artificial Selection on Primorsky Krai Territory

Gukov, G.V, Rozlomiy, N.G. /Vol. 8 Núm. 18: 432- 437/ Enero-febrero 2019 432 Articulo de investigación Biological and environmental peculiarities of tricholoma caligatum (viv) ricken and artificial selection on Primorsky Krai territory Particularidades biológicas y ambientales de tricholoma caligatum (viv) ricken y selección artificial en el territorio de Primorsky Krai Particularidades biológicas e ambientais do tricomaloma caligatum (vida) e seleção artificial no território do Krai de Primorsky Recibido: 16 de enero de 2019. Aceptado: 06 de febrero de 2019 Written by: Gukov G.V. (Corresponding Author)133 Rozlomiy N.G.134 Abstract Resumen Matsutake mushroom is unique in many ways - it El hongo Matsutake es único en muchos has several names, including two Latin ones, aspectos: tiene varios nombres, entre ellos dos mycorhiza developer, and selects individual latinos, desarrollador de micorhiza, y selecciona conifers or hardwood specifically as the partners coníferas individuales o madera dura from woody plant species in different countries. específicamente como socios de especies de It is hidden and very shy - the main part of its fruit plantas leñosas en diferentes países. Es oculto y body (leg) is hidden in soil, and the small compact muy tímido: la parte principal de su cuerpo frutal cap of the fungus is not always visible in forest (pierna) está oculta en el suelo, y la pequeña capa among the fallen autumn needles and leaves. The compacta del hongo no siempre es visible en el mushroom is also unique as it has exceptional bosque entre las hojas y las agujas otoñales nutritional and medicinal properties, therefore caídas. El hongo también es único ya que tiene the price for this unique species exceeds all propiedades nutricionales y medicinales reasonable limits. -

Cretaceous Deposits and Flora of the Muravyov Amurskii Peninsula

ISSN 08695938, Stratigraphy and Geological Correlation, 2015, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 281–299. © Pleiades Publishing, Ltd., 2015. Original Russian Text © E.B. Volynets, 2015, published in Stratigrafiya. Geologicheskaya Korrelyatsiya, 2015, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 50–68. Cretaceous Deposits and Flora of the MuravyovAmurskii Peninsula (Amur Bay, Sea of Japan) E. B. Volynets Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Far East Branch, Russian Academy of Sciences, pr. 100letiya Vladivostoka 159, Vladivostok, 690022 Russia email: [email protected] Received August 21, 2013; in final form, March 24, 2014 Abstract—The Cretaceous sections and plant macrofossils are investigated in detail near Vladivostok on the MuravyovAmurskii Peninsula of southern Primorye. It is established that the Ussuri and Lipovtsy forma tions in the reference section of the Markovskii Peninsula rest with unconformity upon Upper Triassic strata. The continuous Cretaceous succession is revealed in the Peschanka River area of the northern Muravyov Amurskii Peninsula, where plant remains were first sampled from the lower and upper parts of the Korkino Group, which are determined to be the late Albian–late Cenmanian in age. The taxonomic composition of floral assemblages from the Ussuri, Lipovtsy, and Galenki formations is widened owing to additional finds of plant remains. The Korkino Group received floral characteristics for the first time. The Cretaceous flora of the peninsula is represented by 126 taxa. It is established that ferns and conifers are dominant elements of the Ussuri floral assemblage, while the Lipovtsy Assemblage is dominated by ferns, conifers, and cycadphytes. In addition, the latter assemblage is characterized by the highest taxonomic diversity. The Galenki Assemblage is marked by the first appearance of rare flowering plants against the background of dominant ferns and coni fers. -

Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences

ISSN: 0975-8585 Research Journal of Pharmaceutical, Biological and Chemical Sciences Concentration of Gold from Ash and Slag Wastes of Energy Sector Enterprises of The Primorsky Territory. Evgeny Ivanovich Shamray1*, Andrey Vasilyevich Taskin2, Sergey Igorevich Ivannikov1, and Alexander Alekseevich Yudakov1. 1 Institute of chemistry FEB RAS, 690022, Russia, Vladivostok, Prosp. 100-letya Vladivostoka, 159. 2Far Eastern Federal University, 690091, Russia, Vladivostok, Sukhanova str., 8. ABSTRACT The study of a large array of ash waste from landfills of energy sector enterprises in Primorsky Territory was made. Data on the content of gold and silver in the ash and slug waste of some energy enterprises in Primorsky Territory was given. Group of samples with high content of gold and silver was found. Silver content was found within 0.5-29.7 g/t limits. Gold content was found within 0.004–0.45 g/t limits. The information on the chemical composition of the investigated slag samples was given. Based on these data, the method of separation of ash and slag waste in the individual mineral fractions was proposed. The possibility of gold concentration in the non-magnetic fraction of the slag cleared of silt, clay, black charcoal and magnetic minerals was shown. Keywords: technogenic deposits, wastes of energy enterprises, ash and slag waste (ASW), gold, silver, atomic and absorption analysis, neutron-activation analysis, X-ray fluorescence analysis. *Corresponding Author November – December 2016 RJPBCS 7(6) Page No. 156 ISSN: 0975-8585 INTRODUCTION Ash and slag waste (ASW) is formed during coal combustion process in energy producing enterprises. For example, in recent years, yearly inflow of ASW into the ash and slag disposal areas of Primorsky Territory is up to 3.0 million tons. -

Primorsky Railway Port

Baltiysky Primorsky Tamansky Development of dry ports of JSC Russian Railways as part of the implementation of the Concept for the Establishment of Terminal and Logistics Centers in the Russian Federation UNESCAP Working group on Dry Ports November 25th 2015, Bangkok, Thailand In 2012, the Board of Directors of JSC Russian Railways approved the Concept for the Establishment of Terminal and Logistics Centers (TLC) in the Russian Federation Priority arrangements to establish a TLC network TLC Kaliningrad Baltiysky Railway Port TLC Bely Rast TLC Doskino Tamansky Railway Port Primorsky Railway Port Grodekovo Nakhodka Artem-Primorsky-I Legend: Facilities of the first phase of the development of the TLC network Key satellites of the first phase 2 A railway port as a comprehensive solution Main functions: . Removal of non-core operations from seaports (storage, stripping, etc.); . Consolidation (of shipload lots, train lots, etc.); . Distribution (port, region, continent, transit, etc.); . Storage (including exchange storage); . Provision of a package of services with added value; . Customs clearance of cargoes. Implementation of transportation technologies with the use of a railway port makes it possible to: . Increase the processing capacity of seaports; . Increase the efficiency of the transportation process; . Cut transport costs; . Reduce the investment burden on port infrastructure, ensure a more rapid commissioning of facilities; . Reduce the likelihood of the emergence of idle trains; . Reduce the environmental footprint and traffic load. 3 Engagement between JSC Russian Impact Railways and seaports • Involvement of JSC . Establishment of a systemic transport Russian Railways in infrastructure facility to implement the just-in-time principle; the management and capital of seaports . -

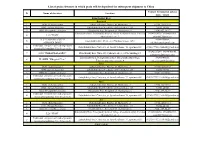

List of Grain Elevators in Which Grain Will Be Deposited for Subsequent Shipment to China

List of grain elevators in which grain will be deposited for subsequent shipment to China Contact Infromation (phone № Name of elevators Location num. / email) Zabaykalsky Krai Rapeseed 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsky district, village Starotsuruhaytuy, Pertizan 89145160238, 89644638969, 4 LLS "PION" Shestakovich str., 3 [email protected] LLC "ZABAYKALSKYI 89144350888, 5 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 149/1 AGROHOLDING" [email protected] Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 6 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich 89242727249, 89144700140, 7 OOO "ZABAYKALAGRO" Zabaykalsky krai, Chita city, Chkalova street, 147A, building 15 [email protected] Zabaykalsky krai, Priargunsky district, Staroturukhaitui village, 89245040356, 8 IP GKFH "Mungalov V.A." Tehnicheskaia street, house 4 [email protected] Corn 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. Urozhaynaya, 6 (924) 457-30-27 Individual entrepreneur head of peasant 4 Zabaykalskyi krai, Chita city, st. Juravleva/home 74, apartment 88 89243877133, [email protected] farming Kalashnikov Uriy Sergeevich Rice 1 ООО «Zabaykalagro» Zabaykalsku krai, Borzya, ul. Matrosova, 2 8-914-120-29-18 2 OOO «Zolotoy Kolosok» Zabaykalsky Krai, Nerchinsk, ul. Octyabrskaya, 128 30242-44948 3 OOO «Priargunskye prostory» Zabaykalsky Krai, Priargunsk ul. -

Sunrise Russia Mission

Vladivostok Sunrise Russia Mission Mary Mother of God Mission Society: Reviving the Roman Catholic Church in Eastern Russia Issue Number One Hundred Fifty Seven January, 2021 in finding sponsors and spiritual mentoring, volunteers of The Work of the centers have saved many lives of unborn babies and the Women’s supported many families and single mothers in difficult times. Support The main goal of the program is to preserve the life of Centers the unborn child. Volunteers perform the following tasks: ● spiritual support for women in crisis pregnancy; By Nadezhda Morozova ● taking care of the health of the mother and the newborn; Caritas Women’s Support ● help with post-abortion syndrome; Centers of Primorye ● collection of donations in the form of clothing and shoes; The 18th of November ● search for sponsors. was the 100th anniversary Tasks are performed using these programs: of the legalization of abortion in Soviet Russia. The legalization of abortion then spread to other Baby Talk countries, which led to the From the Women’s Support Centers unprecedentedly large number of murdered children, and also to a change in the mentality of society in which abortion became a normal fact of life. Russia still ranks first in terms of the number of abortions in the world, and therefore the need to provide assistance to women in crisis pregnancy situations is still great. Contraception is mistakenly considered to be the only means of preventing abortion, so our task is also to educate women about alternative methods of natural family planning. As a result of the consequences of abortion and oral contraception, the incidence of uterine cancer and breast cancer is increasing, which affects the health of the family and the nation. -

Moscow Defense Brief Your Professional Guide Inside # 2, 2011

Moscow Defense Brief Your Professional Guide Inside # 2, 2011 Troubled Waters CONTENTS Defense Industries #2 (24), 2011 Medium-term Prospects for MiG Corporation PUBLISHER After Interim MMRCA Competition Results 2 Centre for Russian Helicopter Industry: Up and Away 4 Analysis of Strategies and Technologies Arms Trade CAST Director & Publisher Exports of Russian Fighter Jets in 1999-2010 8 Ruslan Pukhov Editor-in-Chief Mikhail Barabanov International Relations Advisory Editors Georgian Lesson for Libya 13 Konstantin Makienko Alexey Pokolyavin Researchers Global Security Ruslan Aliev Polina Temerina Missile Defense: Old Problem, No New Solution 15 Dmitry Vasiliev Editorial Office Armed Forces 3 Tverskaya-Yamskaya, 24, office 5, Moscow, Russia 125047 Reform of the Russian Navy in 2008-2011 18 phone: +7 499 251 9069 fax: +7 495 775 0418 http://www.mdb.cast.ru/ Facts & Figures To subscribe, contact Incidents Involving Russian Submarines in 1992-2010 23 phone: +7 499 251 9069 or e-mail: [email protected] 28 Moscow Defense Brief is published by the Centre for Analysis of Strategies Our Authors and Technologies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without reference to Moscow Defense Brief. Please note that, while the Publisher has taken all reasonable care in the compilation of this publication, the Publisher cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions in this publication or for any loss arising therefrom. Authors’ opinions do not necessary reflect those of the Publisher or Editor Translated by: Ivan Khokhotva Computer design & pre-press: B2B design bureau Zebra www.zebra-group.ru Cover Photo: K-433 Svyatoy Georgiy Pobedonosets (Project 667BDR) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine at the Russian Pacific Fleet base in Vilyuchinsk, February 25, 2011. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Sunrise 84 for Internet

Vladivostok Sunrise Mary Mother of God Mission Society and Vladivostok Mission Issue Number Eighty Four November 1, 2008 Sixteen Years of Charity; Ten Years for the Women’s Support Centers By V Rev Myron Effing, C.J.D. The Caritas volunteers assembled for a special blessing after Sunday Mass on October 12, 2008. On Sunday October 12, as we celebrated Thanksgiving in Project, Women Prisoners’ Project, Children’s Back-to- Vladivostok, we decided to celebrate the 16 years of work School Project, Children’s Facial Correction Surgery of our charitable organization Caritas, and especially Program, Sunday Club Program, Children’s Diabetic because it was also the tenth anniversary of the Caritas Program. Of course we haven’t included programs of Women’s Support Centers. There are already 1000 babies evangelization, education, spiritual growth, and support who have been helped by the Adopt-a-Birth program, and for parishes in this list, even. that is just the tip of the iceberg as far as the charity that has been performed by the remarkable symbiosis of our donors and of our volunteers. I just thought I’d list some things that have been done: Adopt-a-birth, Adopt-a-Mom, Adriana Adopt-a-Family, Hospice for the Dying, Elderly Home Michael- Visiting Project, Hope Medical Project, Street Children ovna, Project, Medical Center, Vladivostok Water Crisis Project, received a Primorye Flood Aid Project, Renovabis Anti-Crisis special project, Alcoholics Anonymous, Just Say No to Narcotics, award as WSC’s seven Centers, Children’s Diabetes Project, Boy the most Scouts, Soup Kitchen Project, Fruit and Milk Orphans committed Project, Grandma Mentoring Project, Save the Children volunteer.