Theory and Practice in Language Studies Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Speech Sounds Vowels HOPE

This is the Cochlear™ promise to you. As the global leader in hearing solutions, Cochlear is dedicated to bringing the gift of sound to people all over the world. With our hearing solutions, Cochlear has reconnected over 250,000 cochlear implant and Baha® users to their families, friends and communities in more than 100 countries. Along with the industry’s largest investment in research and development, we continue to partner with leading international Speech Sounds:Vowels researchers and hearing professionals, ensuring that we are at the forefront in the science of hearing. A Guide for Parents and Professionals For the person with hearing loss receiving any one of the Cochlear hearing solutions, our commitment is that for the rest of your life in English and Spanish we will be here to support you Hear now. And always Ideas compiled by CASTLE staff, Department of Otolaryngology As your partner in hearing for life, Cochlear believes it is important that you understand University of North Carolina — Chapel Hill not only the benefits, but also the potential risks associated with any cochlear implant. You should talk to your hearing healthcare provider about who is a candidate for cochlear implantation. Before any cochlear implant surgery, it is important to talk to your doctor about CDC guidelines for pre-surgical vaccinations. Cochlear implants are contraindicated for patients with lesions of the auditory nerve, active ear infections or active disease of the middle ear. Cochlear implantation is a surgical procedure, and carries with it the risks typical for surgery. You may lose residual hearing in the implanted ear. -

The Motor Coordination Reasoning in Acting Dancer's Performance

Review Article J Phy Fit Treatment & Sports Volume 2 Issue 4 - March 2018 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Cláudia Tarragô Candotti DOI: 10.19080/JPFMTS.2018.02.555593 The Motor Coordination Reasoning in Acting Dancer’s Performance Improvement and Injury Prevention Kaanda Nabilla Souza Gontijo1, Carla Itatiana Bastos de Brito2, Cláudia Tarragô Candotti3* and Adriane Vieira4 1Graduate Program in Human Movement Sciences, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 2Department of Physiotherapy, IPA Methodist University Center, Brazil 3Ph.D. Professor of the Graduate Program in Human Movement Sciences, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil 4School of Physical Education, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil Submission: March 16, 2018; Published: March 27, 2018 *Corresponding author: Cláudia Tarragô Candotti, Ph.D. Professor of the Graduate Program in Human Movement Sciences, Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil; Tel: ; Fax: +55 (51) 3308-5843; Email: Abstract Many injuries that affect classical dancers are caused by compensations made to overcome anatomical limitations, which cause a proper coordination loss between the body segments. This lesions appearance, ultimately, results in people giving up on the practice even after different types of rehabilitation conventional treatments application. Given this reality, we argue for a physical therapy line focused on posture and movement re-education, based on Motor Coordination (MC), as described by Piret and Béziers, since we consider it has great potential not only to improve the dancers’ performance, but to prevent and treat injuries. So our goal in this article is to express our opinion on how MC principles can contribute to the classical ballet teaching-learning-training process and to the dancer’s preventive treatments and rehabilitation with regard to their lower limbs arrangement. -

Dança Break: Aspectos Históricos, Fundamentos E Elementos Competitivos”

UNVERSIDADE DO VALE DO PARAÍBA FACULDADE DE EDUCAÇÃO E ARTES CURSO DE EDUCAÇÃO FÍSICA "DANÇA BREAK: ASPECTOS HISTÓRICOS, FUNDAMENTOS E ELEMENTOS COMPETITIVOS”. Marcelo Rodolfo Bento São José dos Campos/ SP 2015 UNVERSIDADE DO VALE DO PARAÍBA FACULDADE DE EDUCAÇÃO E ARTES CURSO DE EDUCAÇÃO FÍSICA TRABALHO DE CONCLUSÃO DE CURSO MARCELO RODOLFO BENTO Relatório final apresentado como parte das exigências da disciplina. Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso à Coordenação de TCC do curso de Educação Física da Faculdade de Educação e Artes da Universidade do Vale do Paraíba. Orientador: Profº. Me. Cláudio Alexandre Cunha São José dos Campos/SP 2015 Agradecimento Primeiramente agradeço à Deus, por me abençoar e iluminar minha mente e meu caminho, minha família por toda importância que ela tem em minha vida, minha mãe Fátima de Jesus Bento que me ensinou que devemos lutar por nossos sonhos, minha amada esposa, Fabiana Braga Moreira que sempre me incentivou a estudar e acompanhou toda minha luta e compartilhou comigo todos esses momentos de desafios, superações e conquistas ao longo desse processo. Professor Cláudio Alexandre Cunha que aceitou o desafio de ser meu orientador e parceiro. Há todos, que de alguma forma contribuíram e fizeram parte da construção do que sou como pessoa, estudante, pesquisador e profissional, meus sinceros agradecimentos e que Deus abençoe grandiosamente todos vocês. Dedicatória Dedico esse trabalho a meu filho, Davi Moreira Bento que foi um presente de Deus na minha e à todos os B. boys que por meio da dança, foram minha inspiração para a realização este estudo. Resumo A Dança Break, oriunda dos guetos norte americanos em meados de 1970, evoluiu muito desde sua criação e atualmente possui milhares de praticantes e campeonatos por todo o mundo. -

Tesis Completa

DEPARTAMENT DE PSICOLOGIA EVOLUTIVA I DE L’EDUCACIÓ OPTIMIZACIÓN EN PROCESOS COGNITIVOS Y SU REPERCUSIÓN EN EL APRENDIZAJE DE LA DANZA. Mª ISABEL MEGÍAS CUENCA UNIVERSITAT DE VALÈNCIA Servei de Publicacions 2009 Aquesta Tesi Doctoral va ser presentada a València el dia 28 de setembre de 2009 davant un tribunal format per: - Dra. María Vicenta Mestre Escrivá - Dra. Reyes Fiz Poveda - Dra. Ana María Flori López - Dr. José Lozano Rodríguez - Dr. José Manuel Tomás Miguel Va ser dirigida per: Dr. Ángel Latorre Latorre ©Copyright: Servei de Publicacions Mª Isabel Megías Cuenca Dipòsit legal: V-958-2011 I.S.B.N.: 978-84-370-7725-3 Edita: Universitat de València Servei de Publicacions C/ Arts Gràfiques, 13 baix 46010 València Spain Telèfon:(0034)963864115 Optimización en procesos cognitivos y su repercusión en el aprendizaje de la danza UNIVERSITAT DE VALÈNCIA FACULTAT DE PSICOLOGÍA DEPARTAMENT DE PSICOLOGÍA EVOLUTIVA I DE LA EDUCACIÓ OPTIMIZACIÓN EN PROCESOS COGNITIVOS Y SU REPERCUSIÓN EN EL APRENDIZAJE DE LA DANZA TESIS DOCTORAL PRESENTADA POR: Mª ISABEL MEGÍAS CUENCA DIRIGIDA POR: Dr. ANGEL LATORRE LATORRE VALENCIA, Febrero de 2009 1 Optimización en procesos cognitivos y su repercusión en el aprendizaje de la danza AGRADECIMIENTOS Después de una labor tan entregada, como ha sido la realización de esta tesis, además del orgullo por haber logrado una meta importante en mi vida, prevalece el sentimiento de agradecimiento a quienes me han acompañado en esta aventura, a veces incomprendida. En primer lugar, no cabe duda de que la primera persona que creyó en mi propuesta y dio forma a mis inquietudes, fue Ángel Latorre. -

Conference Schedule

ICBBS 2019 CONFERENCE ABSTRACT CONFERENCE ABSTRACT 2019 8th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Science (ICBBS 2019) October 23-25, 2019 Grand Gongda Jianguo Hotel, Beijing, China Organized by Co-organized by Published and Indexed by http://www.icbbs.org/ ICBBS 2019 CONFERENCE ABSTRACT ICBBS 2019 CONFERENCE ABSTRACT Table of Contents Introduction 4 Conference Committee 5~6 Program at-a-Glance 7~9 Presentation Instruction 10 Keynote Speaker Introduction 11~19 Invited Speaker Introduction 20~21 Oral Session on October 24, 2019 Session 1: Feature Extraction and Image Segmentation 22~26 Session 2: Pattern Recognition and Image Classification 27~31 Session 3: Medical Image Processing and Medical Testing 32~37 Session 4: Data Analysis and Soft Computing 38~42 Session 5: Target Detection 43~47 Session 6: Image Analysis and Signal Processing 48~53 Session 7: Molecular Biology and Biomedicine 54~59 Session 8: Computer Information Technology and Application 60~64 Poster Session on October 25, 2019 65~84 Conference Venue 85~86 Note 87~88 ICBBS 2019 CONFERENCE ABSTRACT Introduction Welcome to 2019 8th International Conference on Bioinformatics and Biomedical Science (ICBBS 2019) which is organized by Beijing University of Technology and Biology and Bioinformatics (BBS) under Hong Kong Chemical, Biological & Environmental Engineering Society (CBEES), co-organized by Tiangong University and Hebei University of Technology. The objective of ICBBS 2019 is to provide a platform for researchers, engineers, academicians as well as industrial professionals from all over the world to present their research results and development activities in Bioinformatics and Biomedical Science. Papers will be published in the following proceedings: ACM Conference Proceedings (ISBN: 978-1-4503-7251-0): archived in ACM Digital Library, indexed by EI Compendex and SCOPUS, and submitted to be reviewed by Thomson Reuters Conference Proceedings Citation Index (ISI Web of Science). -

University of Leeds Chinese Accepted Institution List 2021

University of Leeds Chinese accepted Institution List 2021 This list applies to courses in: All Engineering and Computing courses School of Mathematics School of Education School of Politics and International Studies School of Sociology and Social Policy GPA Requirements 2:1 = 75-85% 2:2 = 70-80% Please visit https://courses.leeds.ac.uk to find out which courses require a 2:1 and a 2:2. Please note: This document is to be used as a guide only. Final decisions will be made by the University of Leeds admissions teams. -

Danças Contemporâneas E Processos Coreográficos No Tempo Presente

Universidade Federal de Goiás DANÇAS CONTEMPORÂNEAS E PROCESSOS COREOGRÁFICOS NO TEMPO PRESENTE Vanessa Duarte Voskelis De Carvalho Barbosa GOIÂNIA 2021 UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE GOIÁS FACULDADE DE EDUCAÇÃO FÍSICA E DANÇA TERMO DE CIÊNCIA E DE AUTORIZAÇÃO PARA DISPONIBILIZAR VERSÕES ELETRÔNICAS DE TRABALHO DE CONCLUSÃO DE CURSO DE GRADUAÇÃO NO REPOSITÓRIO INSTITUCIONAL DA UFG Na qualidade de titular dos direitos de autor, autorizo a Universidade Federal de Goiás (UFG) a disponibilizar, gratuitamente, por meio do Repositório Institucional (RI/UFG), regulamentado pela Resolução CEPEC no 1240/2014, sem ressarcimento dos direitos autorais, de acordo com a Lei no 9.610/98, o documento conforme permissões assinaladas abaixo, para fins de leitura, impressão e/ou download, a título de divulgação da produção científica brasileira, a partir desta data. O conteúdo dos Trabalhos de Conclusão dos Cursos de Graduação disponibilizado no RI/UFG é de responsabilidade exclusiva dos autores. Ao encaminhar(em) o produto final, o(s) autor(a)(es)(as) e o(a) orientador(a) firmam o compromisso de que o trabalho não contém nenhuma violação de quaisquer direitos autorais ou outro direito de terceiros. 1. Identificação do Trabalho de Conclusão de Curso de Graduação (TCCG) Nome(s) completo(s) do(a)(s) autor(a)(es)(as): VANESSA DUARTE VOSKELIS DE CARVALHO BARBOSA Título do trabalho: Danças Contemporâneas e processos coreográficos no tempo presente 2. Informações de acesso ao documento (este campo deve ser preenchido pelo orientador) Concorda com a liberação total do documento [ X ] SIM [ ] NÃO¹ [1] Neste caso o documento será embargado por até um ano a partir da data de defesa. -

Proper Pesticide Application in Agricultural Products €

Food Control 122 (2021) 107788 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Food Control journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodcont Review Factors influencing Chinese farmers’ proper pesticide application in agricultural products – A review Yingxuan Pan a,1, Yingxue Ren b,1, Pieternel A. Luning a,* a Food Quality and Design, Department of Agrotechnology and Food Sciences, Wageningen University, P.O. Box 17, 6700 AA, Wageningen, the Netherlands b Management Science, School of Economics and Management, TianGong University, 300387, Tianjin, PR China ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Pesticide residues in agricultural products are a persistent food safety issue in China. The current review aims to Chinese farmers get a comprehensive understanding of factors influencing farmers’ proper pesticide application in China. To Pesticide application achieve that, the study developed an analytical framework based on the principles of the Theory of Planned Theory of Planned Behaviour Behaviour (TPB) and the techno-managerial approach. Following the framework, the study conducted a semi- Techno-managerial approach structured literature review and yielded multiple factors related to farmers (i.e. their characteristics and TPB Interventions elements), external circumstances (i.e. governmental supervision, the roles of suppliers and the support of extension services) and technological conditions (i.e. equipment and environmental conditions), which can in fluence pesticide application of farmers. To improve farmers’ behaviour, a stepwise approach of interventions targeted to different actors was proposed. Future research on the effectiveness of the application of the stepwise interventions on pesticide use is suggested. 1. Introduction like toxic cowpeas in southern China (Huan, Xu, Luo, & Xie, 2016). Several studies indicated that pesticide residues relate to the Pesticides are widely used against pest in agricultural production behaviour of farmers, specifically their pesticide application (Jallow, (WHO, 2017). -

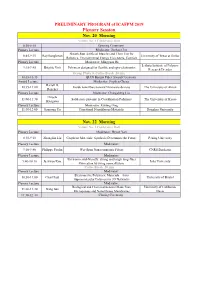

2019ICAFPM-PRELIMINARY PROGRAM-07112019.Xlsx

PRELIMINARY PROGRAM of ICAFPM 2019 Plenary Session Nov. 20 Morning Venue: No. 1 Conference Hall 8:30-8:45 Opening Ceremony Plenary Lecture Moderator: Junhao Chu Sheath-Run Artificial Muscles and Their Use for 8:45-9:15 Ray Baughman University of Texas at Dallas Robotics, Environmental Energy Harvesters, Comfort Plenary Lecture Moderator: Mingyuan He Leibniz Institute of Polymer 9:15-9:45 Brigitte Voit Polymers designed for flexible and opto-electronics Research Dresden Group Photo & Coffee Break 20 min 10:05-10:35 QIAN Baojun Fiber Award Ceremony Award Lecture Moderator: Stephen Cheng Darrell H. 10:35-11:00 Inside nanofibers toward Nanoware devices The University of Akron Reneker Plenary Lecture Moderator: Changsheng Liu Hiroshi 11:00-11:30 Solid-state protonic in Coordination Polymers The University of Kyoto Kitagawa Plenary Lecture Moderator: Kuiling Ding 11:30-12:00 Jianyong Yu Functional Nanofibrous Materials Donghua University Nov. 22 Morning Venue: No. 1 Conference Hall Plenary Lecture Moderator: Deyue Yan 8:30-9:10 Zhongfan Liu Graphene Materials: Synthesis Determines the Future Peking University Plenary Lecture Moderator: 9:10-9:40 Philippe Poulin Wet-Spun Nanocomposite Fibers CNRS Bordeaux Plenary Lecture Moderator: Environmental-friendly, strong and tough long-fiber 9:40-10:10 Jaehwan Kim Inha University fabrication by using nanocellulose Coffee Break 20 min Plenary Lecture Moderator: Electroactive Polymeric Materials – from 10:30-11:00 Charl Faul University of Bristol Supramolecular Polymers to 3D Networks Plenary Lecture Moderator: Biological and Chemical Sensors Made from University of California, 11:00-11:30 Gang Sun Microporous and Nanofibrous Membranes Davis 11:30-12:00 Closing Ceremony PRELIMINARY PROGRAM of ICAFPM 2019 Parallel Session Nov. -

Sport Research Effects of Dance In

MLS - SPORT RESEARCH https://www.mlsjournals.com/Sport-Research How to cite this article: López Campo, N. (2021). Effects of dancing in patients with Parkinson's disease: systematic review. MLS Sport Research, 1(1), 35-50. EFFECTS OF DANCE IN PATIENTS WITH PARKINSON: SYSTEMATIC REVIEW Noelia López Campo Universidad Europea del Atlántico (Spain) [email protected] Abstract. The aim of this review was to find out the effects of different dance programmes on the improvement of symptoms and quality of life in patients with Parkinson's disease (PD), as well as to determine the possible differences depending on the type of dance modality used. A systematic review of different dance programmes was carried out in three databases (Google Scholar, Pubmed and Dialnet). We included 14 trials with a total of 469 participants and evaluated different dance modalities, which showed favourable results on motor function, cognitive function and quality of life in people with PD. The modality of tango, followed by samba, seems to be the most suitable for this type of disease, producing greater improvements in balance, speed of movement and gait pattern, due to its variety of movements and characteristic marked rhythm. However, the two most challenging dances were the waltz and the cha-cha- cha, due to the crossing of the feet, changes of direction and less grip. Although there is a need for continued research and longer programs, the analysis of results suggests that dancing can be an effective treatment for PD patients, as there is a decrease in symptoms and therefore an improvement in quality of life. -

Conference Program

CONFERENCE PROGRAM 2020 6th International Conference on Computing and Artificial Intelligence (ICCAI 2020) & 2020 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Medicine and Image Processing (IMIP 2020) April 23-26, 2020|Tianjin, China Organized by Supported by Gold Sponsor Table of Contents 1. Welcome Letter 3 2. Presentation Guideline 4 3. ZOOM User Guideline 6 4. Program-at-a-Glance 7 4.1 Test Session Schedule 7 4.2 Formal Session Schedule 8 5. Keynote Speaker 10 6. Invited Speaker 14 7. Detailed Program for Poster Session 17 7.1 Poster Session 1--Topic: “Computer Vision and Image Processing Technology” 17 7.2 Poster Session 2--Topic: “Modern Information Theory and Applied Technology” 19 8. Detailed Program for Oral Session 21 8.1 Oral Session 1--Topic: “Machine Learning and Intelligent Computing” 21 8.2 Oral Session 2--Topic: “Next-generation Neural Network and Applications” 22 8.3 Oral Session 3--Topic: “Data Analysis and Processing” 23 8.4 Oral Session 4--Topic: “Big Data Science and Information Intelligence” 24 8.5 Oral Session 5--Topic: “Target Detection” 25 8.6 Oral Session 6--Topic: “Image Transformation and Calculation” 26 8.7 Oral Session 7--Topic: “Intelligent Identification and Control Technology” 27 8.8 Oral Session 8--Topic: “Medical Image Analysis and Processing” 28 8.9 Oral Session 9--Topic: “Computer Network and Information Communication System” 29 8.10 Oral Session 10--Topic: “Computer and Information Science” 30 9. About ICCAI 2021&IMIP 2021 31 2 Welcome Letter Dear distinguished delegates, On behalf of the organizing committee, I would like to express my sincere thanks to all of you for participating in 2020 6th International Conference on Computing and Artificial Intelligence (ICCAI 2020) and 2020 2nd International Conference on Intelligent Medicine and Image Processing (IMIP 2020) which will be held during April 23-26, 2020. -

EDTA for Adsorptive Removal of Sulfamethoxazole

Desalination and Water Treatment 207 (2020) 321–331 www.deswater.com December doi: 10.5004/dwt.2020.26391 Magnetic porous Fe–C materials prepared by one-step pyrolyzation of NaFe(III)EDTA for adsorptive removal of sulfamethoxazole Jiandong Zhua,†, Liang Wanga,†, Yawei Shia,*, Bofeng Zhangb, Yajie Tianc, Zhaohui Zhanga, Bin Zhaoa, Guozhu Liub,*, Hongwei Zhanga,d aState Key Laboratory of Separation Membranes and Membrane Processes, School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Tiangong University, Tianjin 300387, China, Tel./Fax: +86 22 83955392; emails: [email protected] (Y.W. Shi), [email protected] (J.D. Zhu), [email protected] (L. Wang), [email protected] (Z.H. Zhang), [email protected] (B. Zhao), [email protected] (H.W. Zhang) bSchool of Chemical Engineering and Technology, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China, Tel. +86 22 27892340; emails: [email protected] (G.Z. Liu), [email protected] (B.F. Zhang) cHenan Engineering Research Center of Resource & Energy Recovery from Waste, College of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Henan University, Kaifeng 475004, China, email: [email protected] (Y.J. Tian) dSchool of Environmental Science and Engineering, Tianjin University, Tianjin 300072, China Received 25 February 2020; Accepted 25 July 2020 abstract A series of magnetic porous Fe–C materials were prepared by one-step pyrolyzation of ethylene- diaminetetraacetic acid sodium iron(III) at 500°C–800°C and then employed as adsorbents for sulfamethoxazole (SMX) adsorption. The one prepared at 700°C (Fe–C-700) was selected as the opti- mum one with an adsorption amount of 82.3 mg g–1 at pH 5.0 and 30°C.