G Protein‐Coupled Receptors

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Therapeutic Medications Against Diabetes: What We Have and What We Expect

Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 139 (2019) 3–15 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/addr Therapeutic medications against diabetes: What we have and what we expect Cheng Hu a,b, Weiping Jia a,⁎ a Shanghai Diabetes Institute, Shanghai Key Laboratory of Diabetes Mellitus, Shanghai Key Clinical Center for Metabolic Diseases, Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People's Hospital, 600 Yishan Road, Shanghai 200233, People's Republic of China b Shanghai Jiao Tong University Affiliated Sixth People's Hospital South Campus, 6600 Nanfeng Road, Shanghai 200433, People's Republic of China article info abstract Article history: Diabetes has become one of the largest global health and economic burdens, with its increased prevalence and Received 28 June 2018 high complication ratio. Stable and satisfactory blood glucose control are vital to reduce diabetes-related compli- Received in revised form 1 September 2018 cations. Therefore, continuous attempts have been made in antidiabetic drugs, treatment routes, and traditional Accepted 27 November 2018 Chinese medicine to achieve better disease control. New antidiabetic drugs and appropriate combinations of Available online 5 December 2018 these drugs have increased diabetes control significantly. Besides, novel treatment routes including oral antidia- betic peptide delivery, nanocarrier delivery system, implantable drug delivery system are also pivotal for diabetes Keywords: fi Diabetes control, with its greater ef ciency, increased bioavailability, decreased toxicity and reduced dosing frequency. Treatment Among these new routes, nanotechnology, artificial pancreas and islet cell implantation have shown great poten- Drug delivery tial in diabetes therapy. Traditional Chinese medicine also offer new options for diabetes treatment. -

The Orphan Receptor GPR17 Is Unresponsive to Uracil Nucleotides and Cysteinyl Leukotrienes S

Supplemental material to this article can be found at: http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org/content/suppl/2017/03/02/mol.116.107904.DC1 1521-0111/91/5/518–532$25.00 https://doi.org/10.1124/mol.116.107904 MOLECULAR PHARMACOLOGY Mol Pharmacol 91:518–532, May 2017 Copyright ª 2017 by The American Society for Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics The Orphan Receptor GPR17 Is Unresponsive to Uracil Nucleotides and Cysteinyl Leukotrienes s Katharina Simon, Nicole Merten, Ralf Schröder, Stephanie Hennen, Philip Preis, Nina-Katharina Schmitt, Lucas Peters, Ramona Schrage,1 Celine Vermeiren, Michel Gillard, Klaus Mohr, Jesus Gomeza, and Evi Kostenis Molecular, Cellular and Pharmacobiology Section, Institute of Pharmaceutical Biology (K.S., N.M., Ral.S., S.H., P.P., N.-K.S, L.P., J.G., E.K.), Research Training Group 1873 (K.S., E.K.), Pharmacology and Toxicology Section, Institute of Pharmacy (Ram.S., K.M.), University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany; UCB Pharma, CNS Research, Braine l’Alleud, Belgium (C.V., M.G.). Downloaded from Received December 16, 2016; accepted March 1, 2017 ABSTRACT Pairing orphan G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs) with their using eight distinct functional assay platforms based on label- cognate endogenous ligands is expected to have a major im- free pathway-unbiased biosensor technologies, as well as molpharm.aspetjournals.org pact on our understanding of GPCR biology. It follows that the canonical second-messenger or biochemical assays. Appraisal reproducibility of orphan receptor ligand pairs should be of of GPR17 activity can be accomplished with neither the coapplica- fundamental importance to guide meaningful investigations into tion of both ligand classes nor the exogenous transfection of partner the pharmacology and function of individual receptors. -

Edinburgh Research Explorer

Edinburgh Research Explorer International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list Citation for published version: Davenport, AP, Alexander, SPH, Sharman, JL, Pawson, AJ, Benson, HE, Monaghan, AE, Liew, WC, Mpamhanga, CP, Bonner, TI, Neubig, RR, Pin, JP, Spedding, M & Harmar, AJ 2013, 'International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXVIII. G protein-coupled receptor list: recommendations for new pairings with cognate ligands', Pharmacological reviews, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 967-86. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1124/pr.112.007179 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: Pharmacological reviews Publisher Rights Statement: U.S. Government work not protected by U.S. copyright General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 1521-0081/65/3/967–986$25.00 http://dx.doi.org/10.1124/pr.112.007179 PHARMACOLOGICAL REVIEWS Pharmacol Rev 65:967–986, July 2013 U.S. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

The 'C3ar Antagonist' SB290157 Is a Partial C5ar2 Agonist

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.01.232090; this version posted August 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. The ‘C3aR antagonist’ SB290157 is a partial C5aR2 agonist Xaria X. Li1, Vinod Kumar1, John D. Lee1, Trent M. Woodruff1* 1School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, 4072 Australia. * Correspondence: Prof. Trent M. Woodruff School of Biomedical Sciences, The University of Queensland, St Lucia, 4072 Australia. Ph: +61 7 3365 2924; Fax: +61 7 3365 1766; E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: Complement C3a, C3aR, SB290157, C5aR1, C5aR2 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.08.01.232090; this version posted August 3, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. Abbreviations used in this article: BRET, bioluminescence resonance energy transfer; BSA, bovine serum albumin; C3aR, C3a receptor C5aR1, C5a receptor 1; CHO-C3aR, Chinese hamster ovary cells stably expressing C3aR; CHO-C5aR1, Chinese hamster ovary cells stably expressing C5aR1; DMEM, Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium; ERK1/2, extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2; FBS, foetal bovine serum; HEK293, human embryonic kidney 293 cells; HMDM, human monocyte-derived macrophage; i.p., intraperitoneal; i.v., intravenous; rhC5a, recombinant human C5a; RT, room temperature; S.E.M. -

Reck and Gpr124 Activate Canonical Wnt Signaling To

RECK AND GPR124 ACTIVATE CANONICAL WNT SIGNALING TO CONTROL MAMMALIAN CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM ANGIOGENESIS AND BLOOD-BRAIN BARRIER REGULATION by Chris Moonho Cho A dissertation submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Baltimore, Maryland July 2018 © Chris Moonho Cho 2018 All rights reserved Abstract Canonical Wnt signaling plays a pivotal role in promoting central nervous system (CNS) angiogenesis and blood-brain barrier (BBB) formation and maintenance. Specifically, Wnt7a and Wnt7b are required for vascular development in the forebrain and ventral spinal cord. Yet, how these two ligands – among the 19 mammalian Wnts – are selectively communicated to Frizzled receptors expressed on endothelial cells (ECs) remains largely unclear. In this thesis, we propose a novel paradigm for Wnt specificity. We have identified two EC surface proteins – orphan receptor Gpr124, and more recently, GPI-anchored Reck (reversion-inducing cysteine-rich protein with Kazal motifs) – as essential receptor co-factors that assemble into a multi-protein complex with Wnt7a/7b and Frizzled for the development of the mammalian neurovasculature. Specifically, we show that EC-specific reduction in Reck impairs CNS angiogenesis and that EC-specific postnatal loss of Reck, combined with loss of Norrin, impairs BBB maintenance. We identify the critical domains of both Reck and Gpr124 that are required for Wnt activity, and demonstrate that these regions are important for ii direct binding and complex formation. Importantly, weakening this interaction by targeted mutagenesis reduces Reck-Gpr124 stimulation of Wnt7a signaling in cell culture and impairs CNS angiogenesis. Finally, a soluble Gpr124 probe binds specifically to cells expressing Frizzled (Fz), Wnt7a or Wnt7b, and Reck; and a soluble Reck probe binds specifically to cells expressing Fz, Wnt7a or Wnt7b, and Gpr124. -

Neutrophil Chemoattractant Receptors in Health and Disease: Double-Edged Swords

Cellular & Molecular Immunology www.nature.com/cmi REVIEW ARTICLE Neutrophil chemoattractant receptors in health and disease: double-edged swords Mieke Metzemaekers1, Mieke Gouwy1 and Paul Proost 1 Neutrophils are frontline cells of the innate immune system. These effector leukocytes are equipped with intriguing antimicrobial machinery and consequently display high cytotoxic potential. Accurate neutrophil recruitment is essential to combat microbes and to restore homeostasis, for inflammation modulation and resolution, wound healing and tissue repair. After fulfilling the appropriate effector functions, however, dampening neutrophil activation and infiltration is crucial to prevent damage to the host. In humans, chemoattractant molecules can be categorized into four biochemical families, i.e., chemotactic lipids, formyl peptides, complement anaphylatoxins and chemokines. They are critically involved in the tight regulation of neutrophil bone marrow storage and egress and in spatial and temporal neutrophil trafficking between organs. Chemoattractants function by activating dedicated heptahelical G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). In addition, emerging evidence suggests an important role for atypical chemoattractant receptors (ACKRs) that do not couple to G proteins in fine-tuning neutrophil migratory and functional responses. The expression levels of chemoattractant receptors are dependent on the level of neutrophil maturation and state of activation, with a pivotal modulatory role for the (inflammatory) environment. Here, we provide an overview -

Targeting Lysophosphatidic Acid in Cancer: the Issues in Moving from Bench to Bedside

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by IUPUIScholarWorks cancers Review Targeting Lysophosphatidic Acid in Cancer: The Issues in Moving from Bench to Bedside Yan Xu Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Indiana University School of Medicine, 950 W. Walnut Street R2-E380, Indianapolis, IN 46202, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-317-274-3972 Received: 28 August 2019; Accepted: 8 October 2019; Published: 10 October 2019 Abstract: Since the clear demonstration of lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)’s pathological roles in cancer in the mid-1990s, more than 1000 papers relating LPA to various types of cancer were published. Through these studies, LPA was established as a target for cancer. Although LPA-related inhibitors entered clinical trials for fibrosis, the concept of targeting LPA is yet to be moved to clinical cancer treatment. The major challenges that we are facing in moving LPA application from bench to bedside include the intrinsic and complicated metabolic, functional, and signaling properties of LPA, as well as technical issues, which are discussed in this review. Potential strategies and perspectives to improve the translational progress are suggested. Despite these challenges, we are optimistic that LPA blockage, particularly in combination with other agents, is on the horizon to be incorporated into clinical applications. Keywords: Autotaxin (ATX); ovarian cancer (OC); cancer stem cell (CSC); electrospray ionization tandem mass spectrometry (ESI-MS/MS); G-protein coupled receptor (GPCR); lipid phosphate phosphatase enzymes (LPPs); lysophosphatidic acid (LPA); phospholipase A2 enzymes (PLA2s); nuclear receptor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR); sphingosine-1 phosphate (S1P) 1. -

The Roles Played by Highly Truncated Splice Variants of G Protein-Coupled Receptors Helen Wise

Wise Journal of Molecular Signaling 2012, 7:13 http://www.jmolecularsignaling.com/content/7/1/13 REVIEW Open Access The roles played by highly truncated splice variants of G protein-coupled receptors Helen Wise Abstract Alternative splicing of G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) genes greatly increases the total number of receptor isoforms which may be expressed in a cell-dependent and time-dependent manner. This increased diversity of cell signaling options caused by the generation of splice variants is further enhanced by receptor dimerization. When alternative splicing generates highly truncated GPCRs with less than seven transmembrane (TM) domains, the predominant effect in vitro is that of a dominant-negative mutation associated with the retention of the wild-type receptor in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). For constitutively active (agonist-independent) GPCRs, their attenuated expression on the cell surface, and consequent decreased basal activity due to the dominant-negative effect of truncated splice variants, has pathological consequences. Truncated splice variants may conversely offer protection from disease when expression of co-receptors for binding of infectious agents to cells is attenuated due to ER retention of the wild-type co-receptor. In this review, we will see that GPCRs retained in the ER can still be functionally active but also that highly truncated GPCRs may also be functionally active. Although rare, some truncated splice variants still bind ligand and activate cell signaling responses. More importantly, by forming heterodimers with full-length GPCRs, some truncated splice variants also provide opportunities to generate receptor complexes with unique pharmacological properties. So, instead of assuming that highly truncated GPCRs are associated with faulty transcription processes, it is time to reassess their potential benefit to the host organism. -

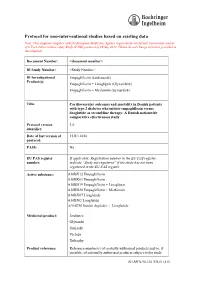

Protocol for Non-Interventional Studies Based on Existing Data

ABCD TITLE PAGE Protocol for non-interventional studies based on existing data TITLE PAGE Note: This template complies with the European Medicines Agency requirements on format, layout and content of a Post Authorisation safety Study (PASS) protocol of 26 Sep 2012. Please do not change structure provided in this template. Document Number: <document number> BI Study Number: <Study Number> BI Investigational Empagliflozin (Jardiance®) Product(s): Empagliflozin + Linagliptin (Glyxambi®) Empagliflozin + Metformin (Synjardy®) Title: Cardiovascular outcomes and mortality in Danish patients with type 2 diabetes who initiate empagliflozin versus liraglutide as second-line therapy: A Danish nationwide comparative effectiveness study Protocol version 1.0 identifier: Date of last version of 15JUL2018 protocol: PASS: No EU PAS register If applicable: Registration number in the EU PAS register; number: indicate “Study not registered” if the study has not been registered in the EU PAS register Active substance: A10BX12 Empagliflozin A10BK03 Empagliflozin A10BD19 Empagliflozin + Linagliptin A10BD20 Empagliflozin + Metformin A10BX07 Liraglutide A10BJ02 Liraglutide A10AE56 Insulin degludec + Liraglutide Medicinal product: Jardiance Glyxambi Synjardy Victoza Xultophy Product reference: Reference number(s) of centrally authorised products and/or, if possible, of nationally authorised products subject to the study 001-MCS-90-124_RD-01 (4.0) Boehringer Ingelheim Page 2 of 55 Protocol for non-interventional studies based on existing data BI Study Number <Study Number> <document number> Proprietary confidential information © 2019 Boehringer Ingelheim International GmbH or one or more of its affiliated companies Procedure number: If applicable, Agency or national procedure number(s), e.g. EMA/X/X/XXX Joint PASS: No Research question and To compare, among patients with type 2 diabetes in Denmark, objectives: clinical outcomes among new users (initiators) of empagliflozin versus liraglutide. -

G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Gpr17 Regulates Oligodendrocyte

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN G-Protein-Coupled Receptor Gpr17 Regulates Oligodendrocyte Diferentiation in Response Received: 11 May 2017 Accepted: 2 October 2017 to Lysolecithin-Induced Published: xx xx xxxx Demyelination Changqing Lu1,2, Lihua Dong2, Hui Zhou3, Qianmei Li3, Guojiao Huang3, Shu jun Bai3 & Linchuan Liao1 Oligodendrocytes are the myelin-producing cells of the central nervous system (CNS). A variety of brain disorders from “classical” demyelinating diseases, such as multiple sclerosis, stroke, schizophrenia, depression, Down syndrome and autism, are shown myelination defects. Oligodendrocyte myelination is regulated by a complex interplay of intrinsic, epigenetic and extrinsic factors. Gpr17 (G protein- coupled receptor 17) is a G protein-coupled receptor, and has been identifed to be a regulator for oligodendrocyte development. Here, we demonstrate that the absence of Gpr17 enhances remyelination in vivo with a toxin-induced model whereby focal demyelinated lesions are generated in spinal cord white matter of adult mice by localized injection of LPC(L-a-lysophosphatidylcholine). The increased expression of the activated form of Erk1/2 (phospho-Erk1/2) in lesion areas suggested the potential role of Erk1/2 activity on the Gpr17-dependent modulation of myelination. The absence of Gpr17 enhances remyelination is correlate with the activated Erk1/2 (phospho-Erk1/2).Being a membrane receptor, Gpr17 represents an ideal druggable target to be exploited for innovative regenerative approaches to acute and chronic CNS diseases. Oligodendrocytes are the myelin-producing cells of the central nervous system (CNS), and as such, wrap layers of lipid-dense insulating myelin around axons1. Mature oligodendrocytes have also been shown to provide met- abolic support to axons through transport systems within myelin, which may help prevent neurodegeneration2. -

Host-Parasite Interaction of Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar) and the Ectoparasite Neoparamoeba Perurans in Amoebic Gill Disease

ORIGINAL RESEARCH published: 31 May 2021 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.672700 Host-Parasite Interaction of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) and the Ectoparasite Neoparamoeba perurans in Amoebic Gill Disease † Natasha A. Botwright 1*, Amin R. Mohamed 1 , Joel Slinger 2, Paula C. Lima 1 and James W. Wynne 3 1 Livestock and Aquaculture, CSIRO Agriculture and Food, St Lucia, QLD, Australia, 2 Livestock and Aquaculture, CSIRO Agriculture and Food, Woorim, QLD, Australia, 3 Livestock and Aquaculture, CSIRO Agriculture and Food, Hobart, TAS, Australia Marine farmed Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) are susceptible to recurrent amoebic gill disease Edited by: (AGD) caused by the ectoparasite Neoparamoeba perurans over the growout production Samuel A. M. Martin, University of Aberdeen, cycle. The parasite elicits a highly localized response within the gill epithelium resulting in United Kingdom multifocal mucoid patches at the site of parasite attachment. This host-parasite response Reviewed by: drives a complex immune reaction, which remains poorly understood. To generate a model Diego Robledo, for host-parasite interaction during pathogenesis of AGD in Atlantic salmon the local (gill) and University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom systemic transcriptomic response in the host, and the parasite during AGD pathogenesis was Maria K. Dahle, explored. A dual RNA-seq approach together with differential gene expression and system- Norwegian Veterinary Institute (NVI), Norway wide statistical analyses of gene and transcription factor networks was employed. A multi- *Correspondence: tissue transcriptomic data set was generated from the gill (including both lesioned and non- Natasha A. Botwright lesioned tissue), head kidney and spleen tissues naïve and AGD-affected Atlantic salmon [email protected] sourced from an in vivo AGD challenge trial.