Museum of Fin Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Joseph Lindon Smith, Whose Realistic Paintings of Interior Tomb Walls Are Featured in the Gallery;

About Fitchburg Art Museum Founded in 1929, the Fitchburg Art Museum is a privately-supported art museum located in north central Massachusetts. Art and artifacts on view: Ancient Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Asian, and Meso-American; European and American paintings (portraits, still lifes, and landscapes) and sculpture from the nineteenth and twentieth centuries; African sculptures from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; Twentieth-century photography (usually); European and American decorative arts; Temporary exhibitions of historical or contemporary art Museum Hours Wednesdays-Fridays, 12 – 4 p.m. Saturdays and Sundays 11 a.m. – 5 p.m. Closed Mondays and Tuesdays, except for the following Monday holidays: Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, President’s Day, Patriot’s Day, and Columbus Day Admission Free to all Museum members and children ages 12 and under. $7.00 Adult non-members, $5.00 Seniors, youth ages 13-17, and full-time students ages 18-21 The Museum is wheelchair accessible. Directions Directions to the Museum are on our website. Address and Phone Number 25 Merriam Parkway, Fitchburg, MA 01420 978-345-4207 Visit our website for more information: www.fitchburgartmuseum.org To Schedule a Tour All groups, whether requesting a guided tour or planning to visit as self-guided, need to contact the Director of Docents to schedule their visit. Guided tours need to be scheduled at least three weeks in advance. Please contact the Director of Docents for information on fees, available tour times, and additional art projects available or youth groups. Museum Contacts Main Number: 978-345-4207 Director of Docents: Ann Descoteaux, ext. -

Lindon Smith Joseph Aegyptologe Maler

Joseph Lindon Smith *11. Oktober 1863 Pawtucket, + 18. Oktober 1950 Rhode Island Gästebücher Bd. III Aufenthalt Schloss Neubeuern: Juli 1894 / 3.- 8. Oktober 1897 / Oktober 1899 (C) http://www.aaa.si.edu/exhibits/pastexhibits/vacations/wall4_2.htm Joseph Lindon Smith war ein amerikanischer Maler, der vor allem für seine außerordentlich treuen und lebendigen Darstellungen von Altertümern, insbesondere ägyptischen Grabreliefs, bekannt war. Er war Gründungsmitglied der Kunstkolonie in Dublin, New Hampshire. Smith wurde am 11. Oktober 1863 in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, als Sohn von Henry Francis Smith, einem Holzfäller, und Emma Greenleaf Smith geboren. Er interessierte sich für ein Kunststudium und wurde an der Schule des Museum of Fine Arts in Boston unterrichtet. Im Herbst 1883 segelte Smith mit seinem Freund und Kommilitonen an der Schule des Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, Frank Weston Benson, nach Paris. Sie teilten sich eine Wohnung in Paris, während sie an der Académie Julian (1883–85) bei William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Jules Joseph Lefebvre und Gustave Boulanger studierten. "Der Geräuschpegel in der Académie Julian ist immer konstant: das Kratzen von Bänken auf dem Boden als Künstlerjockey für eine bessere Sicht auf das Modell, das lebhafte Geplänkel von Dutzenden junger Männer in drei oder vier verschiedenen Sprachen. Die Luft im Studio ist warm und voller Düfte von Leinöl und Terpentin, feuchten Wolljacken und dem Rauch von Pfeifen und Zigaretten. In einer Ecke konzentriert sich Frank Benson darauf, den letzten Schliff zu geben Ein Porträt des Modells, eines hageren alten Mannes. Er wischt sich mit dem Pinsel über seinen Kittel und winkt seinem Freund Joseph Lindon Smith zu. -

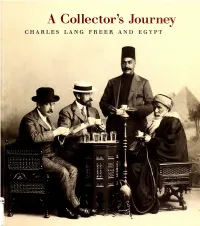

A Collector's Journey : Charles Lang Freer and Egypt / Ann C

A Collector's Journ CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT A Collector's Journey "I now feel that these things are the greatest art in the world," wrote Charles Lang Freer, to a close friend. ". greater than Greek, Chinese or Japanese." Surprising words from the man who created one of the finest collections of Asian art at the turn of the century and donated the collection and funds to the Smithsonian Institution for the construction of the museum that now bears his name, the Freer Gallery of Art. But Freer (1854-1919) became fascinated with Egyptian art during three trips there, between 1906 and 1909, and acquired the bulk of his collection while on site. From jewel-like ancient glass vessels to sacred amulets with supposed magical properties to impressive stone guardian falcons and more, his purchases were diverse and intriguing. Drawing on a wealth of unpublished letters, diaries, and other sources housed in the Freer Gallery of Art Archives, A Collectors Journey documents Freer's expe- rience in Egypt and discusses the place Egyptian art occupied in his notions of beauty and collecting aims. The author reconstructs Freer's journeys and describes the often colorful characters—collectors, dealers, schol- ars, and artists—he met on the way. Gunter also places Freer's travels and collecting in the broader context of American tourism and interest in Egyptian antiquities at the time—a period in which a growing number of Americans, including such financial giants as J. Pierpont Morgan and other Gilded Age barons, were collecting in the same field. A Collector's Journey CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT A Collector's Journey CHARLES LANG FREER AND EGYPT ) Ann C. -

Hieroglyphs and Egyptian Grammar

Selected Bibliography for Ancient Egypt Compiled by Margery Gordon The following bibliography includes useful books only in English, mainly appearing in the last twenty years. It is meant to provide a "starting point" for those interested in researching Ancient Egyptian topics. The books included on this list are on a variety of different reading levels and are likely to appear in school or local public libraries. General information on many of these topics can also be found in encyclopedias. Arts and Crafts • Aldred, Cyril (1980) Egyptian Art in the Days of the Pharaohs. • Andrews, Carol (1991) Ancient Egyptian Jewelry. • Arnold, Dorothea (1999) When the Pyramids were Built. • British Museum (1983). Egyptian Sculpture. By T.G.H. James and W.V. Davies. • Friedman, Florence Dunn (1989) Beyond the Pharaohs: Egypt and the Copts in the 2nd to 7th Centuries A.D. • Friedman, Florence Dunn, editor (1998) Gifts of the Nile: Ancient Egyptian Faience. • Hall, Rosalind (1986) Egyptian Textiles. Shire Egyptology 4. • Hope, Colin A. (1987) Egyptian Pottery. Shire Egyptology 5. Arts and Crafts • James, T.G.H. (1986) Egyptian Painting and Drawing in the British Museum. • Killen, Geoffrey (1994) Egyptian Woodworkers and Furniture. • Killen, Geoffrey (1994) Egyptian Woodworking and Furniture. Shire Egyptology 21. • Lesko, Barbara S. with Diana Wolfe Larkin and Leonard H. Lesko (1998) Joseph Lindon Smith: Paintings from Egypt. An Exhibition: Brown Univeristy, October 8 - November 21, 1998. • Malek, Jaromir (1999) Egyptian Art. • Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (1999) Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. • Michalowski, Kazimierz (1978) Great Sculpture of Ancient Egypt. Arts and Crafts • Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (1982) Egypt's Golden Age: The Art of Living in the New Kingdom, 1558-1085 B.C. -

DUBLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE: HISTORIC RESOURCES INVENTORY Cheshire County

DUBLIN, NEW HAMPSHIRE: HISTORIC RESOURCES INVENTORY Cheshire County 1. DUBLIN LAKE HISTORIC DISTRICT i 2. Dublin, N.H. 03444. jCheshire County. 3. Historic district of occupied properties, both privately and publicly owned, - . comprised entirely o£ residences, seasonal cottages and two clubhouses. j 4. Multiple Ownership, j (See continuation sheets.) 5. Location of Legal Description. Same as overall nomination. Town of Dublin Assessors Property Map and Lot numbers appear in upper right hand corner (Item #22) of:all Individual Inventory forms. 6. Prior Surveys. Same!as overall nomination. 7. Description. (See continuation sheets.) 8. Significance. (See Continuation sheets.) 9. Bibliographical References. Same as overall nomination. 10. Geographical Data: ; A. Acreage: 660 plus 239 water: 899 B. UTM References: j F Z18 E738-J050 N4756-495 G Z18 E736^400 N4753-695 H Z18 E738- 795 N4753-145 J Z18 E739- 600 N4754-725 C. Verbal Boundary Description. i The Dublin Lake District boundary generally follows a line uniformly setback 1000 feet from the shore of Dublin Lake (corresponding to the line extablished in the 1926 Conservation easement) with one indentation to accommodate the Dublin Village District boundary, and four additions to include architec turally and historically significant properties that were integral parts of the late 19th - 0arly 20th century summer colony centered on Dublin Lake. | The boundary is as follows: Commencing at Route 101 at a point 1000 feet east of Dublin Lake, thence south and west on the 1000-foot setback line to the 390,000 East coordinate (N.H. Grid system), thence west along the 1520 foot elevation on the! south side of Lone Tree Hill to the 387,800 East coordinate (N.H. -

Bothmer, Bernard V. Egypt 1950. My First Visit. Edited by Emma Swan

01 BVB frontmatter FINAL Page i Saturday, November 15, 2003 10:56 PM M Y FIRST VISIT EGYPT 1950 MY FIRST VISIT i 01 BVB frontmatter FINAL Page ii Saturday, November 15, 2003 10:56 PM E GYPT 1950 Bernard V. Bothmer at age 38 (1912–1993) ii 01 BVB frontmatter FINAL Page iii Saturday, November 15, 2003 10:56 PM M Y FIRST VISIT Egypt 1950 My First Visit BY BERNARD V. BOTHMER Edited by Emma Swan Hall Oxbow Books 2003 iii 01 BVB frontmatter FINAL Page iv Saturday, November 15, 2003 10:56 PM E GYPT 1950 A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library This book is available direct from Oxbow Books, Park End Place, Oxford OX1 1HN (Tel: 01865-241249; Fax: 01865-794449) www.oxbowbooks.com and The David Brown Book Company PO Box 511 Oakville CT 06779 (Tel: 860-945-9329; Fax: 860-945-9468) www.davidbrownbookco.com Typeset in Centaur Typeset, designed, and produced by Peter Der Manuelian ISBN 1-842170131-3 © 2003 Emma Swan Hall All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, without prior permission in writing from the publisher Printed in the United States of America by Sawyer Printers, Charlestown, Massachusetts Bound by Acme Bookbinding, Charlestown, Massachusetts iv 01 BVB frontmatter FINAL Page v Saturday, November 15, 2003 10:56 PM M Y FIRST VISIT CONTENTS List of Photographs . vii Foreword . xiii Preface . xv Titles of Egyptian Officials . -

A Finding Aid to the Joseph Lindon Smith Papers, 1647-1965, Bulk 1873-1965, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Joseph Lindon Smith Papers, 1647-1965, bulk 1873-1965, in the Archives of American Art Jean Fitzgerald March 10, 2010 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 2 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 2 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 3 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 4 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 5 Series 1: Biographical Material, 1711-1948............................................................. 5 Series 2: Letters, 1768-1965.................................................................................... 6 Series 3: Diaries, 1904-1949.................................................................................. 18 Series 4: Personal Business -

The Art Museum : [Bulletin]

WELLESLEY COLLEGE BULLETIN THE ART MUSEUM WELLESLEY, MASSACHUSETTS FIRST YEAR JUNE 1923 NUMBER I A POLYCLITAN FIGURE Marble. Height, 4 ft. 3 in. Purchased in 1905 from M. Day Kimball Memo- rial Fund. Gift of Miss Hannah Parker Kimball SERIES 12 NUMBER 7 2 WELLESLEY COLLEGE ART MUSEUM THE ART MUSEUM BULLETIN The Wellesley College Art Museum is undertaking the publication at intervals of a bulletin. The main object is to bring information to interested alumnae and friends in regard to gifts and other matters of art importance to the College and to keep them in touch with changes and policies. This bulletin will be modelled upon the bulletins published by many American art museums, with such adaptations as local conditions suggest. What the character of the bulletin shall eventually be, and whether it can give opportunity for alumnae criticisms and suggestions on College Art problems, the reception accorded this initial issue may determine. Interior of Gallery THE MUSEUM The Museum as distinct from the Art Department may be said to have begun with the pur- chase by Mrs. Durant, almost at the time of the founding of the College, of vestments and laces from the Jarvis Collection,—the collection from which Yale University secured its extraor- dinary collection of Early Italian paintings. Since then, from time to time additions of value have been made. Miss Helen Gould presented a most valuable section of the Murch Egyptian Collection. 1 The late Mrs. Whitin (of the Board of Trustees) secured other Egyptian objects. Mrs. Rufus S. Frost, a missionary for many years among the North American Indians, pre- sented her valuable collection of Indian baskets. -

Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2001

ARCHIV ORIENTALNf Quarterly Journal of African and Asian Studies Volume 70 Number 3 August 2002 PRAHA ISSN 0044-8699 Archiv orientalni Quarterly Journal of African and Asian Studies Volume 70 (2002) No.3 Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2001 Proceedings of the Symposium (Prague, September 25th-27th, 2001) - Bdited by Filip Coppens, Czech National Centre of Bgyptology Contents Opening Address (LadisZav BareS) . .. 265-266 List of Abbreviations 267-268 Hartwig AZtenmiiller: Funerary Boats and Boat Pits of the Old Kingdom 269-290 The article deals with the problem of boats and boat pits of royal and non-royal provenance. Start- ing from the observation that in the Old Kingdom most of the boats from boat gra ves come in pairs or in a doubling of a pair the boats of the royal domain are compared with the pictorial representa- tions of the private tombs of the Old Kingdom where the boats appear likewise in pairs and in ship convoys. The analysis of the ship scenes of the non-royal tomb complexes of the Old Kingdom leads to the result that the boats represented in the tomb decoration of the Old Kingdom are used during the night and day voyage of the tomb owner. Accordingly the ships in the royal boat graves are considered to be boats used by the king during his day and night journey. MirosZav Barta: Sociology of the Minor Cemeteries during the Old Kingdom. A View from Abusir South 291-300 In this contribution, the Abusir evidence (the Fetekty cemetery from the Late Fifth Dynasty) is used to demonstrate that the notions of unstratified cemeteries for lower rank officials and of female burials from the residential cemeteries is inaccurate. -

Direct PDF Link for Archiving

Isabel Taube exhibition review of Americans in Paris, 1860–1900 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 6, no. 1 (Spring 2007) Citation: Isabel Taube, exhibition review of “Americans in Paris, 1860–1900,” Nineteenth- Century Art Worldwide 6, no. 1 (Spring 2007), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/ spring07/132-americans-in-paris-18601900. Published by: Association of Historians of Nineteenth-Century Art Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. ©2007 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide Taube: Americans in Paris, 1860–1900 Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 6, no. 1 (Spring 2007) Americans in Paris, 1860–1900 National Gallery, London 22 February – 21 May, 2006 The Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 25 June – 24 September, 2006 The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York 17 October 2006 – 28 January 2007 Americans in Paris, 1860–1900 Kathleen Adler, Erica E. Hirshler, H. Barbara Weinberg with contributions from David Park Curry, Rodolphe Rapetti and Christopher Riopelle. Exhibition catalogue. London: National Gallery Company Limited, 2006. Hardcover distributed by Yale University Press. 320 pp; 240 color ills.; 20 b/w ills.; index; $65.00 (hardcover); $40 (paperback) ISBN 1 85709 301 1 (hardcover); ISBN 1 85709 306 2 (paperback) View a short film of the exhibition (.mov). Quicktime only. Americans in Paris, 1860–1900 was a long overdue exhibition that aimed to explore, as the introductory wall label stated, "why Paris was a magnet for Americans, what they found there and how they responded to it, and which lessons they ultimately brought back to the United States." Organized by an international team of curators— Kathleen Adler from the National Gallery, London; Erica E. -

Annual Report of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2016 with funding from Getty Research Institute https://archive.org/details/annualreportofmu1915muse MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, BOSTON FORTIETH ANNUAL REPORT FOR THE YEAR 1915 BOSTON T. O. Metcalf Company 1916 1 CONTENTS PAGE Trustees of the Museum 5 Officers and Committees for 1916 6 The Staff of the Museum 10 Report of the President 1 Minute on the Death of John Chipman Gray ... 23 Report of the Treasurer 25 Annual Subscribers for the current year ... 51 Report of the Director 75 Reports of Curators and others : Department of Prints 84 Department of Classical Art 96 Department of Chinese and Japanese Art . 101 Department of Egyptian Art in Department of Paintings 114 Department of Western Art : Textiles 127 Other Collections 131 The Librarian 14 The Secretary of the Museum 150 The Supervisor of Educational Work .... 155 Report of the Committee on the School of the Museum 168 Publications by Officers of the Museum 174 Index of Donors and Lenders 175 TRUSTEES OF THE MUSEUM Named in Act of Incorporation, Febncary 4, 1870, or since Elected CHARLES WILLIAM ELIOT February 4, 1870 DENMAN WALDO ROSS January 17, 1895 HENRY SARGENT HUNNEWELL January 19, 1899 CHARLES SPRAGUE SARGENT January 18, 1900 FRANCIS LEE HIGGINSON January 18, 1900 MORRIS GRAY January 16, 1902 EDWARD WALDO FORBES April 28, 1903 A. SHUMAN January 17, 1907 THOMAS ALLEN April 15, 1909 THEODORE NELSON VAIL January 19, 1911 GEORGE ROBERT WHITE January 19,1911 ALEXANDER COCHRANE . January 16, 1913 AUGUSTUS HEMENWAY January 16, 1913 WILLIAM CROWNINSHIELD -

The Lost Throne of Queen Hetepheres from Giza: an Archaeological Experiment in Visualization and Fabrication

The Lost Throne of Queen Hetepheres from Giza: An Archaeological Experiment in Visualization and Fabrication PETER DER MANUELIAN Abstract In 1925, one of the greatest discoveries made at Giza revealed a small, unfinished chamber (labeled “G 7000 X”) more than twenty-seven meters underground, just east of the Great Pyramid. The Harvard University–Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition found there the deteriorated burial equipment, sarcophagus, and other objects be- longing to Queen Hetepheres I, presumed consort of Snefru and mother of Khufu. Since the discovery of this rare Old Kingdom royal assemblage, the thousands of small fragments have remained in storage in the Egyptian Museum, Cairo. Meticulous documentation allowed the excavators to reconstruct some of the queen’s furniture. However, the most exquisite piece, her “second” chair or throne, made of cedar with hundreds of faience inlays and completely gilded, was never reconstructed. This paper describes an interdisciplinary collaboration initiated by the Giza Project at Harvard University to create a full-scale reproduction of Hetepheres’s second chair in modern cedar, faience, gold, gesso, and copper. The goals for this visualization experiment were to reconstruct the excavation history, the iconog- raphy, and to document, insofar as possible, the ancient workflow the Egyptians used to construct this Old Kingdom masterpiece. The final results produced a new museum display object and research/teaching tool. Two significant features of Hetepheres’s tomb complex stand out today. One