The Beethoven Arrangements Published by Sigmund Anton Steiner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schubert's!Voice!In!The!Symphonies!

! ! ! ! A!Search!for!Schubert’s!Voice!in!the!Symphonies! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Camille!Anne!Ramos9Klee! ! Submitted!to!the!Department!of!Music!of!Amherst!College!in!partial!fulfillment! of!the!requirements!for!the!degree!of!Bachelor!of!Arts!with!honors! ! Faculty!Advisor:!Klara!Moricz! April!16,!2012! ! ! ! ! ! In!Memory!of!Walter!“Doc”!Daniel!Marino!(191291999),! for!sharing!your!love!of!music!with!me!in!my!early!years!and!always!treating!me!like! one!of!your!own!grandchildren! ! ! ! ! ! ! Table!of!Contents! ! ! Introduction! Schubert,!Beethoven,!and!the!World!of!the!Sonata!! 2! ! ! ! Chapter!One! Student!Works! 10! ! ! ! Chapter!Two! The!Transitional!Symphonies! 37! ! ! ! Chapter!Three! Mature!Works! 63! ! ! ! Bibliography! 87! ! ! Acknowledgements! ! ! First!and!foremost!I!would!like!to!eXpress!my!immense!gratitude!to!my!advisor,! Klara!Moricz.!This!thesis!would!not!have!been!possible!without!your!patience!and! careful!guidance.!Your!support!has!allowed!me!to!become!a!better!writer,!and!I!am! forever!grateful.! To!the!professors!and!instructors!I!have!studied!with!during!my!years!at! Amherst:!Alison!Hale,!Graham!Hunt,!Jenny!Kallick,!Karen!Rosenak,!David!Schneider,! Mark!Swanson,!and!Eric!Wubbels.!The!lessons!I!have!learned!from!all!of!you!have! helped!shape!this!thesis.!Thank!you!for!giving!me!a!thorough!music!education!in!my! four!years!here!at!Amherst.! To!the!rest!of!the!Music!Department:!Thank!you!for!creating!a!warm,!open! environment!in!which!I!have!grown!as!both!a!student!and!musician.!! To!the!staff!of!the!Music!Library!at!the!University!of!Minnesota:!Thank!you!for! -

A Register of Music Performed in Concert, Nazareth, Pennsylvania from 1796 to 1845: an Annotated Edition of an American Moravian Document

A register of music performed in concert, Nazareth, Pennsylvania from 1796 to 1845: an annotated edition of an American Moravian document Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Strauss, Barbara Jo, 1947- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 10/10/2021 23:14:00 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/347995 A REGISTER OF MUSIC PERFORMED IN CONCERT, NAZARETH., PENNSYLVANIA FROM 1796 TO 181+52 AN ANNOTATED EDITION OF AN AMERICAN.MORAVIAN DOCUMENT by Barbara Jo Strauss A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF MUSIC In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF MUSIC WITH A MAJOR IN MUSIC HISTORY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 7 6 Copyright 1976 Barbara Jo Strauss STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The Univer sity of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate ac knowledgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manu script in whole or in part may -

1 Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D Minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion

1 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony #9 in D minor, Op. 125 2 Johann Sebastian Bach St. Matthew Passion "Ebarme dich, mein Gott" 3 George Frideric Handel Messiah: Hallelujah Chorus 4 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony 41 C, K.551 "Jupiter" 5 Samuel Barber Adagio for Strings Op.11 6 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Clarinet Concerto A, K.622 7 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto 5 E-Flat, Op.73 "Emperor" (3) 8 Antonin Dvorak Symphony No 9 (IV) 9 George Gershwin Rhapsody In Blue (1924) 10 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem in D minor K 626 (aeternam/kyrie/lacrimosa) 11 George Frideric Handel Xerxes - Largo 12 Johann Sebastian Bach Toccata And Fugue In D Minor, BWV 565 (arr Stokowski) 13 Ludwig van Beethoven Symphony No 5 in C minor Op 67 (I) 14 Johann Sebastian Bach Orchestral Suite #3 BWV 1068: Air on the G String 15 Antonio Vivaldi Concerto Grosso in E Op. 8/1 RV 269 "Spring" 16 Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor 17 Edvard Grieg Peer Gynt 1, Op.46 18 Sergei Rachmaninov Piano Concerto No 2 in C minor Op 18 (I) 19 Ralph Vaughan Williams Lark Ascending 20 Gustav Mahler Symphony 5 C-Sharp Min (4) 21 Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky 1812 Overture 22 Jean Sibelius Finlandia, Op.26 23 Johann Pachelbel Canon in D 24 Carl Orff Carmina Burana: O Fortuna, In taberna, Tanz 25 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Serenade G, K.525 "Eine Kleine Nachtmusik" 26 Johann Sebastian Bach Brandenburg Concerto No 5 in D BWV 1050 (I) 27 Johann Strauss II Blue Danube Waltz, Op.314 28 Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Trio 39 G, Hob.15-25 29 George Frideric Handel Water Music Suite #2 in D 30 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Ave Verum Corpus, K.618 31 Johannes Brahms Symphony 1 C Min, Op.68 32 Felix Mendelssohn Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. -

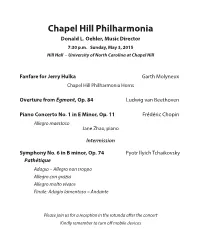

Concert Program

Chapel Hill Philharmonia Donald L. Oehler, Music Director 7:30 p.m. Sunday, May 3, 2015 Hill Hall – University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Garth Molyneux Chapel Hill Philharmonia Horns Overture from Egmont, Op. 84 Ludwig van Beethoven Piano Concerto No. 1 in E Minor, Op. 11 Frédéric Chopin Allegro maestoso Jane Zhao, piano Intermission Symphony No. 6 in B minor, Op. 74 Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky Pathétique Adagio – Allegro non troppo Allegro con grazia Allegro molto vivace Finale: Adagio lamentoso – Andante Please join us for a reception in the rotunda after the concert Kindly remember to turn off mobile devices Pathétique The Romantic era idealized heroes. The works on tonight’s Chapel Hill Philharmonia program comprise three dis- tinct takes on heroism—the martyrdom of a leader to the cause of freedom, the creativity of an artist in the face of an incurable illness, and the passionate suffering of an individual descending into silence. Fanfare for Jerry Hulka Jaroslav Hulka, M.D., passed away on November 24, 2014, at age 84. A founding member of the CHP and long time principal French horn player, Jerry also served the orchestra as a board member and president. He is survived by his wife Barbara Sorenson Hulka, a UNC-Chapel Hill professor emerita and former CHP concertmaster. The couple met as undergraduates when both were section princi- pals in the Harvard/Radcliffe Orchestra. The Hulkas have donated generously to the CHP and to classical music programs at UNC- Chapel Hill and throughout the Triangle. In his “day job” Jerry was a well-respected academic and obstetrics/gynecology specialist, recognized as a wise physician, mentor, and innovator. -

A Senior Recital

Senior Recitals Recitals 4-7-2008 A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals Part of the Music Performance Commons Repository Citation Hansen, A. (2008). A Senior Recital. 1-1. Available at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/music_senior_recitals/1 This Music Program is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Music Program in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Music Program has been accepted for inclusion in Senior Recitals by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. illi1YThe University Of Nevada Las Ve gas Co ll e~e of Fine Arts Ocparlmenl o f Music Pre:senls A Senior Recital Audrey Hansen, ptano ~Program~ ._a Conternplazione: Una Fantasia Piccola, Johann Nepomuk Hummel 1 Op. 107, No.3 (1778-1837) Deux Preludes Claude Achille Debussy Book 1, No.8: La fi/le aux cf7 eueux de /in (1862-1918) Book 2, No. 5: Bruyeres Ballades, Op. 10 Johannes Brahms No. 1 in D minor -Andante (1833-1897) No. 2 in D maj or -Andante No. 3 in B minor -Intermezzo No. 4 in B major - Andante con moto Papillons, Op. -

Johann Nepomuk Hummel's Transcriptions

JOHANN NEPOMUK HUMMEL´S TRANSCRIPTIONS OF BEETHOVEN´S SYMPHONY NO. 2, OP. 36: A COMPARISON OF THE SOLO PIANO AND THE PIANO QUARTET VERSIONS Aram Kim, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2012 APPROVED: Pamela Mia Paul, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor Gustavo Romero, Committee Member Steven Harlos, Chair, Division of Keyboard Studies John Murphy, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music James Scott, Dean of the College of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kim, Aram. Johann Nepomuk Hummel’s Transcriptions of Beethoven´s Symphony No. 2, Op. 36: A Comparison of the Solo Piano and the Piano Quartet Versions. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2012, 30 pp., 2 figures, 13 musical examples, references, 19 titles. Johann Nepomuk Hummel was a noted Austrian composer and piano virtuoso who not only wrote substantially for the instrument, but also transcribed a series of important orchestral pieces. Among them are two transcriptions of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 2 in D Major, Op. 36- the first a version for piano solo and the second a work for piano quartet, with flute substituting for the traditional viola part. This study will examine Hummel’s treatment of the symphony in both transcriptions, looking at a variety of pianistic devices in the solo piano version and his particular instrumentation choices in the quartet version. Each of these transcriptions can serve a particular purpose for performers. The solo piano version is an obvious virtuoso vehicle, whereas the quartet version can be a refreshing program alternative in a piano quartet concert. -

Ludwig Van Beethoven Franz Schubert Wolfgang

STIFTUNG MOZARTEUM SALZBURG WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN PIANO CONCERTO NO. 1 FRANZ SCHUBERT SYMPHONY NO. 5 WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART PIANO CONCERTO NO. 23 ANDRÁS SCHIFF CAPPELLA ANDREA BARCA WEEK LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Vienna - once the music hub of Europe - attracted all the Piano Concerto No. 1 in C major, Op. 15 greatest composers of its day, among them Beethoven, Schubert and Mozart. This concert given by András Schiff and FRANZ SCHUBERT the Capella Andrea Barca during the Salzburg Mozart Week Symphony No. 5 in B flat major, D 485 brings together three works by these great composers, which WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART each of them created early in life at the start of an impressive Piano Concerto No. 23 in E flat major, KV 482 Viennese career. The programme opens with Beethoven’s First Piano Concerto: Piano & Conductor András Schiff “Sensitively supported by the rich and supple tone of the strings, Orchestra Cappella Andrea Barca Schiff’s pianistic virtuosity explores the length and breadth of Beethoven’s early work, from the opulent to the playful, with a Produced by idagio.production palpable delight rarely found in such measure in a pianist”, was Video Director Oliver Becker the admiring verdict of the Salzburg press. Length: approx. 100' As in his opening piece, Schiff again succeeded in Schubert’s Shot in HDTV 1080/50i symphony “from the first note to the last in creating a sound Cat. no. A 045 50045 0000 world that flooded the mind’s eye with images” Drehpunkt( Kultur). A co-production of The climax of the concert was the Mozart piano concerto. -

Opera Olimpiade

OPERA OLIMPIADE Pietro Metastasio’s L’Olimpiade, presented in concert with music penned by sixteen of the Olympian composers of the 18th century VENICE BAROQUE ORCHESTRA Andrea Marcon, conductor Romina Basso Megacle Franziska Gottwald Licida Karina Gauvin Argene Ruth Rosique Aristea Carlo Allemano Clistene Nicholas Spanos Aminta Semi-staged by Nicolas Musin SUMMARY Although the Olympic games are indelibly linked with Greece, Italy was progenitor of the Olympic operas, spawning a musical legacy that continues to resound in opera houses and concert halls today. Soon after 1733, when the great Roman poet Pietro Metastasio witnessed the premiere of his libretto L’Olimpiade in Vienna, a procession of more than 50 composers began to set to music this tale of friendship, loyalty and passion. In the course of the 18th century, theaters across Europe commissioned operas from the Olympian composers of the day, and performances were acclaimed in the royal courts and public opera houses from Rome to Moscow, from Prague to London. Pieto Metastasio In counterpoint to the 2012 Olympic games, Opera Olimpiade has been created to explore and celebrate the diversity of musical expression inspired by this story of the ancient games. Research in Europe and the United States yielded L’Olimpiade manuscripts by many composers, providing the opportunity to extract the finest arias and present Metastasio’s drama through an array of great musical minds of the century. Andrea Marcon will conduct the Venice Baroque Orchestra and a cast of six virtuosi singers—dare we say of Olympic quality—in concert performances of the complete libretto, a succession of 25 spectacular arias and choruses set to music by 16 Title page of David Perez’s L’Olimpiade, premiered in Lisbon in 1753 composers: Caldara, Vivaldi, Pergolesi, Leo, Galuppi, Perez, Hasse, Traetta, Jommelli, Piccinni, Gassmann, Mysliveek, Sarti, Cherubini, Cimarosa, and Paisiello. -

Chapter 5 – the Enlightenment and the American Revolution I. Philosophy in the Age of Reason (5-1) A

Chapter 5 – The Enlightenment and the American Revolution I. Philosophy in the Age of Reason (5-1) A. Scientific Revolution Sparks the Enlightenment 1. Natural Law: Rules or discoveries made by reason B. Hobbes and Lock Have Conflicting Views 1. Hobbes Believes in Powerful Government a. Thomas Hobbes distrusts humans (cruel-greedy-selfish) and favors strong government to keep order b. Promotes social contract—gaining order by giving up freedoms to government c. Outlined his ideas in his work called Leviathan (1651) 2. Locke Advocates Natural Rights a. Philosopher John Locke believed people were good and had natural rights—right to life, liberty, and property b. In his Two Treatises of Government, Lock argued that government’s obligation is to protect people’s natural rights and not take advantage of their position in power C. The Philosophes 1. Philosophes: enlightenment thinkers that believed that the use of reason could lead to reforms of government, law, and society 2. Montesquieu Advances the Idea of Separation of Powers a. Montesquieu—had sharp criticism of absolute monarchy and admired Britain for dividing the government into three branches b. The Spirit of the Laws—outlined his belief in the separation of powers (legislative, executive, and judicial branches) to check each other to stop one branch from gaining too much power 3. Voltaire Defends Freedom of Thought a. Voltaire—most famous of the philosophe who published many works arguing for tolerance and reason—believed in the freedom of religions and speech b. He spoke out against the French government and Catholic Church— makes powerful enemies and is imprisoned twice for his views 4. -

Download Article

International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2016) Russianness in the Works of European Composers Liudmila Kazantseva Department of Theory and History of Music Astrakhan State Concervatoire Astrakhan, Russia E-mail: [email protected] Abstract—For the practice of composing a conscious Russianness is seen more as an exotic). As one more reproduction of native or non-native national style is question I’ll name the ways and means of capturing Russian traditional. As the object of attention of European composers origin. are constantly featured national specificity of Russian culture. At the same time the “hit accuracy” ranges here from a Not turning further on the fan of questions that determine maximum of accuracy (as a rule, when finding a composer in the development of the problems of Russian as other- his native national culture) to a very distant resemblance. The national, let’s focus on only one of them: the reasons which out musical and musical reasons for reference to the Russian encourage European composers in one form or another to culture they are considered in the article. Analysis shows that turn to Russian culture and to make it the subject of a Russiannes is quite attractive for a foreign musicians. However creative image. the European masters are rather motivated by a desire to show, to indicate, to declare the Russianness than to comprehend, to II. THE OUT MUSICAL REASONS FOR REFERENCE TO THE go deep and to get used to it. RUSSIAN CULTURE Keywords—Russian music; Russianness; Western European In general, the reasons can be grouped as follows: out composers; style; polystyle; stylization; citation musical and musical. -

Industrialism, Androids, and the Virtuoso Instrumentalist

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Performing the Mechanical: Industrialism, Androids, and the Virtuoso Instrumentalist A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Musical Arts by Leila Mintaha Nassar-Fredell 2013 © Copyright by Leila Mintaha Nassar-Fredell 2013 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Performing the Mechanical: Industrialism, Androids, and the Virtuoso Instrumentalist by Leila Nassar-Fredell Doctor of Musical Arts University of California, Los Angeles, 2013 Professor Robert S. Winter, Chair Transactions between musical androids and actual virtuosos occupied a prominent place in the music of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Instrumentalists and composers of instrumental music appropriated the craze for clockwork soloists, placing music in a position of increased social power in a society undergoing rapid technological transformation. The history of musical automata stretches back to antiquity. Androids and automata, vested by audiences with spiritual and magical qualities, populated the churches of the broader populations and the Renaissance grottos of the aristocracy. As ii the Industrial Revolution began, automata increasingly resembled the machines changing the structure of labor; consequently, androids lost their enchanted status. Contemporary writers problematized these humanoid machines while at the same time popularizing their role as representatives of the uncanny at the boundaries of human identity. Both instrumental performers and androids explored the liminal area between human and machine. As androids lost their magic, musical virtuosos assumed the qualities of spectacle and spirituality long embodied by their machine counterparts. In this process virtuosi explored the liminal space of human machines: a human playing a musical instrument (a machine) weds the body to a machine, creating a half-human, half-fabricated voice. -

Sacred Music, 136.4, Winter 2009

SACRED MUSIC Winter 2009 Volume 136, Number 4 EDITORIAL Viennese Classical Masses? | William Mahrt 3 ARTICLES Between Tradition and Innovation: Sacred Intersections and the Symphonic Impulse in Haydn’s Late Masses | Eftychia Papanikolaou 6 “Requiem per me”: Antonio Salieri’s Plans for His Funeral | Jane Schatkin Hettrick 17 Haydn’s “Nelson” Mass in Recorded Performance: Text and Context | Nancy November 26 Sunday Vespers in the Parish Church | Fr. Eric M. Andersen 33 REPERTORY The Masses of William Byrd | William Mahrt 42 COMMENTARY Seeking the Living: Why Composers Have a Responsibility to be Accessible to the World | Mark Nowakowski 49 The Role of Beauty in the Liturgy | Fr. Franklyn M. McAfee, D.D. 51 Singing in Unison? Selling Chant to the Reluctant Choir | Mary Jane Ballou 54 ARCHIVE The Lost Collection of Chant Cylinders | Fr. Jerome F. Weber 57 The Ageless Story | Jennifer Gregory Miller 62 REVIEWS A Gift to Priests | Rosalind Mohnsen 66 A Collection of Wisdom and Delight | William Tortolano 68 The Fire Burned Hot | Jeffrey Tucker 70 NEWS The Chant Pilgrimage: A Report 74 THE LAST WORD Musical Instruments and the Mass | Kurt Poterack 76 POSTSCRIPT Gregorian Chant: Invention or Restoration? | William Mahrt SACRED MUSIC Formed as a continuation of Caecilia, published by the Society of St. Caecilia since 1874, and The Catholic Choirmaster, published by the Society of St. Gre- gory of America since 1915. Published quarterly by the Church Music Associ- ation of America. Office of Publication: 12421 New Point Drive, Harbour Cove, Richmond, VA 23233. E-mail: [email protected]; Website: www.musicasacra.com Editor: William Mahrt Managing Editor: Jeffrey Tucker Editor-at-Large: Kurt Poterack Editorial Assistance: Janet Gorbitz and David Sullivan.