The VBJ and the Apache Odyssey by Gene Gade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Extending the Late Holocene White River Ash Distribution, Northwestern Canada STEPHEN D

ARCTIC VOL. 54, NO. 2 (JUNE 2001) P. 157– 161 Extending the Late Holocene White River Ash Distribution, Northwestern Canada STEPHEN D. ROBINSON1 (Received 30 May 2000; accepted in revised form 25 September 2000) ABSTRACT. Peatlands are a particularly good medium for trapping and preserving tephra, as their surfaces are wet and well vegetated. The extent of tephra-depositing events can often be greatly expanded through the observation of ash in peatlands. This paper uses the presence of the White River tephra layer (1200 B.P.) in peatlands to extend the known distribution of this late Holocene tephra into the Mackenzie Valley, northwestern Canada. The ash has been noted almost to the western shore of Great Slave Lake, over 1300 km from the source in southeastern Alaska. This new distribution covers approximately 540000 km2 with a tephra volume of 27 km3. The short time span and constrained timing of volcanic ash deposition, combined with unique physical and chemical parameters, make tephra layers ideal for use as chronostratigraphic markers. Key words: chronostratigraphy, Mackenzie Valley, peatlands, White River ash RÉSUMÉ. Les tourbières constituent un milieu particulièrement approprié au piégeage et à la conservation de téphra, en raison de l’humidité et de l’abondance de végétation qui règnent en surface. L’observation des cendres contenues dans les tourbières permet souvent d’élargir notablement les limites spatiales connues des épisodes de dépôts de téphra. Cet article recourt à la présence de la couche de téphra de la rivière White (1200 BP) dans les tourbières pour agrandir la distribution connue de ce téphra datant de l’Holocène supérieur dans la vallée du Mackenzie, située dans le Nord-Ouest canadien. -

Marine Tephrochronology of the Mt

Quaternary Research 73 (2010) 277–292 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Quaternary Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/yqres Marine tephrochronology of the Mt. Edgecumbe Volcanic Field, Southeast Alaska, USA Jason A. Addison a,b,⁎, James E. Beget a,b, Thomas A. Ager c, Bruce P. Finney d a Alaska Quaternary Center and Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Alaska Fairbanks, 900 Yukon Drive, PO Box 755780, Fairbanks, AK 99775-5780, USA b Alaska Quaternary Center, PO Box 755940, University of Alaska Fairbanks, Fairbanks, AK 99775-5940, USA c U.S. Geological Survey, Mail Stop 980, Box 25045, Denver Federal Center, Denver, CO 80225, USA d Department of Biological Sciences, Idaho State University, Pocatello, ID 83209-8007, USA article info abstract Article history: The Mt. Edgecumbe Volcanic Field (MEVF), located on Kruzof Island near Sitka Sound in southeast Alaska, Received 30 March 2009 experienced a large multiple-stage eruption during the last glacial maximum (LGM)–Holocene transition Available online 11 December 2009 that generated a regionally extensive series of compositionally similar rhyolite tephra horizons and a single well-dated dacite (MEd) tephra. Marine sediment cores collected from adjacent basins to the MEVF contain Keywords: both tephra-fall and pyroclastic flow deposits that consist primarily of rhyolitic tephra and a minor dacitic Tephra tephra unit. The recovered dacite tephra correlates with the MEd tephra, whereas many of the rhyolitic Alaska North Pacific Ocean tephras correlate with published MEVF rhyolites. Correlations were based on age constraints and major Cryptotephra oxide compositions of glass shards. In addition to LGM–Holocene macroscopic tephra units, four marine Mt. -

North American Notes

268 NORTH AMERICAN NOTES NORTH AMERICAN NOTES BY KENNETH A. HENDERSON HE year I 967 marked the Centennial celebration of the purchase of Alaska from Russia by the United States and the Centenary of the Articles of Confederation which formed the Canadian provinces into the Dominion of Canada. Thus both Alaska and Canada were in a mood to celebrate, and a part of this celebration was expressed · in an extremely active climbing season both in Alaska and the Yukon, where some of the highest mountains on the continent are located. While much of the officially sponsored mountaineering activity was concentrated in the border mountains between Alaska and the Yukon, there was intense activity all over Alaska as well. More information is now available on the first winter ascent of Mount McKinley mentioned in A.J. 72. 329. The team of eight was inter national in scope, a Frenchman, Swiss, German, Japanese, and New Zealander, the rest Americans. The successful group of three reached the summit on February 28 in typical Alaskan weather, -62° F. and winds of 35-40 knots. On their return they were stormbound at Denali Pass camp, I7,3oo ft. for seven days. For the forty days they were on the mountain temperatures averaged -35° to -40° F. (A.A.J. I6. 2I.) One of the most important attacks on McKinley in the summer of I967 was probably the three-pronged assault on the South face by the three parties under the general direction of Boyd Everett (A.A.J. I6. IO). The fourteen men flew in to the South east fork of the Kahiltna glacier on June 22 and split into three groups for the climbs. -

Resedimentation of the Late Holocene White River Tephra, Yukon Territory and Alaska

Resedimentation of the late Holocene White River tephra, Yukon Territory and Alaska K.D. West1 and J.A. Donaldson2 Carleton University3 West, K.D. and Donaldson, J.A. 2002. Resedimentation of the late Holocene White River tephra, Yukon Territory and Alaska. In: Yukon Exploration and Geology 2002, D.S. Emond, L.H. Weston and L.L. Lewis (eds.), Exploration and Geological Services Division, Yukon Region, Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, p. 239-247. ABSTRACT The Wrangell region of eastern Alaska represents a zone of extensive volcanism marked by intermittent pyroclastic activity during the late Holocene. The most recent and widely dispersed pyroclastic deposit in this area is the White River tephra, a distinct tephra-fall deposit covering 540 000 km2 in Alaska, Yukon, and the Northwest Territories. This deposit is the product of two Plinian eruptions from Mount Churchill, preserved in two distinct lobes, created ca. 1887 years B.P. (northern lobe) and 1147 years B.P. (eastern lobe). The tephra consists of distal primary air-fall deposits and proximal, locally resedimented volcaniclastic deposits. Distinctive layers such as the White River tephra provide important chronostratigraphic control and can be used to interpret the cultural and environmental impact of ancient large magnitude eruptions. The resedimentation of White River tephra has resulted in large-scale terraces, which fl ank the margins of Klutlan Glacier. Preliminary analysis of resedimented deposits demonstrates that the volcanic stratigraphy within individual terraces is complex and unique. RÉSUMÉ Au cours de l’Holocène tardif, des matériaux pyroclastiques ont été projetés lors d’importantes et nombreuses éruptions volcaniques, dans la région de Wrangell de l’est de l’Alaska. -

P1616 Text-Only PDF File

A Geologic Guide to Wrangell–Saint Elias National Park and Preserve, Alaska A Tectonic Collage of Northbound Terranes By Gary R. Winkler1 With contributions by Edward M. MacKevett, Jr.,2 George Plafker,3 Donald H. Richter,4 Danny S. Rosenkrans,5 and Henry R. Schmoll1 Introduction region—his explorations of Malaspina Glacier and Mt. St. Elias—characterized the vast mountains and glaciers whose realms he invaded with a sense of astonishment. His descrip Wrangell–Saint Elias National Park and Preserve (fig. tions are filled with superlatives. In the ensuing 100+ years, 6), the largest unit in the U.S. National Park System, earth scientists have learned much more about the geologic encompasses nearly 13.2 million acres of geological won evolution of the parklands, but the possibility of astonishment derments. Furthermore, its geologic makeup is shared with still is with us as we unravel the results of continuing tectonic contiguous Tetlin National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska, Kluane processes along the south-central Alaska continental margin. National Park and Game Sanctuary in the Yukon Territory, the Russell’s superlatives are justified: Wrangell–Saint Elias Alsek-Tatshenshini Provincial Park in British Columbia, the is, indeed, an awesome collage of geologic terranes. Most Cordova district of Chugach National Forest and the Yakutat wonderful has been the continuing discovery that the disparate district of Tongass National Forest, and Glacier Bay National terranes are, like us, invaders of a sort with unique trajectories Park and Preserve at the north end of Alaska’s panhan and timelines marking their northward journeys to arrive in dle—shared landscapes of awesome dimensions and classic today’s parklands. -

Alaska Park Science Anchorage, Alaska

National Park Service U.S. Department of Interior Alaska Regional Office Alaska Park Science Anchorage, Alaska PROCEEDINGS OF THE CentrCentralal AlaskAlaskaa PParkark SciencSciencee SymposiumSymposium SeptemberSeptember 12-14,12-14, 2006 2006 Denali Park, Alaska Volume 6, Issue 2 Parks featured in this Table of Contents issue of Alaska Park Science Keynote Address Alaska Parks in a Warming Climate: Conserving a Changing Future __________________________ 6 S K A Yukon-Charley Rivers Synthesis L A National Preserve Crossing Boundaries in Changing Environment: Norton Sound A A Synthesis __________________________________________12 Monitoring a Changing Climate Denali National Park and Preserve Long-term Air Quality Monitoring Wrangell-St. Elias in Denali National Park and Preserve __________________18 National Park and Preserve Monitoring Seasonal and Long-term Climate Changes and Extremes in the Central Alaska Network__________ 22 Physical Environment and Sciences Glacier Monitoring in Denali National Park and Preserve ________________________________________26 Applications of the Soil-Ecological Survey of Denali National Park and Preserve__________________31 Bristol Bay Gulf of Alaska Using Radiocarbon to Detect Change in Ecosystem Carbon Cycling in Response to Permafrost Thawing____34 A Baseline Study of Permafrost in the Toklat Basin, Denali National Park and Preserve ____________________37 Dinosauria and Fossil Aves Footprints from the Lower Cantwell Formation (latest Cretaceous), Denali National Park and Preserve ____________________41 -

Transatlantic Distribution of the Alaskan White River Ash

Transatlantic distribution of the Alaskan White River Ash Britta J.L. Jensen1,2, Sean Pyne-O’Donnell2,3, Gill Plunkett2, Duane G. Froese1, Paul D.M. Hughes4, Michael Sigl5, Joseph R. McConnell5, Matthew J. Amesbury6, Paul G. Blackwell7, Christel van den Bogaard8, Caitlin E. Buck7, Dan J. Charman6, John J. Clague9, Valerie A. Hall2, Johannes Koch9,10, Helen Mackay4, Gunnar Mallon11, Lynsey McColl12, and Jonathan R. Pilcher2 1Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta T6G 2E3, Canada 2School of Geography, Archaeology, and Palaeoecology, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN, UK 3Department of Earth Science, University of Bergen, Allégaten 41, Bergen N-5007, Norway 4Palaeoenvironmental Laboratory (PLUS), Geography and Environment, University of Southampton, Southampton SO17 1BJ, UK 5Desert Research Institute, 2215 Raggio Parkway, Reno, Nevada 89512, USA 6Department of Geography, College of Life and Environmental Sciences, University of Exeter, Exeter EX4 4RJ, UK 7School of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK 8GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, Wischhofstrasse 1-3, Kiel D-24148, Germany 9Department of Earth Sciences, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia V5A 1S6, Canada 10Department of Geography, Brandon University, Brandon, Manitoba R7A 6A9, Canada 11Department of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK 12Select Statistics, Exeter Business Park, Exeter, Devon EX1 3LH, UK ABSTRACT et al., 1995). Deposits from the eruptions are Volcanic ash layers preserved within the geologic record represent precise time markers known as White River Ash north (WRAn), and that correlate disparate depositional environments and enable the investigation of synchro- east (WRAe) (Lerbekmo, 2008). -

Ice Cores from the St. Elias Mountains, Yukon, Canada: Their Significance for Climate, Tmospherica Composition and Volcanism in the North Pacific Region

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Earth Sciences Scholarship Earth Sciences 1-17-2014 Ice Cores from the St. Elias Mountains, Yukon, Canada: Their Significance for Climate, tmosphericA Composition and Volcanism in the North Pacific Region Christian Zdanowicz Geological Survey of Canada David Fisher Geological Survey of Canada Jocelyne Bourgeois Geological Survey of Canada Mike Demuth Geological Survey of Canada James Zheng Geological Survey of Canada See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/earthsci_facpub Recommended Citation Zdanowicz C, D Fisher, J Bourgeois, M Demuth, J Zheng, P Mayewski, K Kreutz, E Osterberg, K Yalcin, C Wake, EJ Steig, D Froese, K Goto-Azuma (2014) Ice Cores from the St. Elias Mountains, Yukon, Canada: Their Significance for Climate, tmosphericA Composition and Volcanism in the North Pacific Region. ARCTIC 67 (Kluane Lake Research Station 50th Anniversary Issue), 35-57. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Earth Sciences at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Earth Sciences Scholarship by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Christian Zdanowicz, David Fisher, Jocelyne Bourgeois, Mike Demuth, James Zheng, Paul A. Mayewski, K Kreutz, Erich Osterberg, Kaplan Yalcin, Cameron P. Wake, Eric J. Steig, Duane Froese, and Kumiko Goto- Azuma This article is available at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository: https://scholars.unh.edu/ earthsci_facpub/514 ARCTIC VOL. 67, SUPPL. 1 (2014) P. 35 – 57 http://dx.doi.org/10.14430/arctic4352 Ice Cores from the St. -

Wrangell-St. Elias Alaska

Wrangell - St. Elias National Park Service National Park and National Preserve U.S. Department of the Interior Wrangell-St. Elias Alaska The wildness of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park The Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation vest harbor seals, which feed on fish and In late summer, black and brown bears, drawn and Preserve is uncompromising, its geography Act (ANILCA) of 1980 allows the subsistence marine invertebrates. These species and many by ripening soapberries, frequent the forests awe-inspiring. Mount Wrangell, namesake of harvest of wildlife within the park, and preserve more are key foods in the subsistence diet of and gravel bars. Human history here is ancient one of the park's four mountain ranges, is an and sport hunting only in the preserve. Hunters the Ahtna and Upper Tanana Athabaskans, and relatively sparse, and has left a light imprint active volcano. Hundreds of glaciers and ice find Dall's sheep, the park's most numerous Eyak, and Tlingit peoples. Local, non-Native on the immense landscape. Even where people fields form in the high peaks, then melt into riv large mammal, on mountain slopes where they people also share in the bounty. continue to hunt, fish, and trap, most animal, ers and streams that drain to the Gulf of Alaska browse sedges, grasses, and forbs. Sockeye, Chi fish, and plant populations are healthy and self and the Bering Sea. Ice is a bridge that connects nook, and Coho salmon spawn in area lakes and Long, dark winters and brief, lush summers lend regulati ng. For the species who call Wrangell the park's geographically isolated areas. -

Geospatial Distribution of Tephra Fall in Alaska: a Geodatabase Compilation of Published Tephra Fall Occurrences from the Pleistocene to the Present

GEOSPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF TEPHRA FALL IN ALASKA: A GEODATABASE COMPILATION OF PUBLISHED TEPHRA FALL OCCURRENCES FROM THE PLEISTOCENE TO THE PRESENT Katherine M. Mulliken, Janet R. Schaefer, Cheryl E. Cameron Miscellaneous Publication 164 $5.00 This publication is PRELIMINARY in nature and meant to allow rapid release of field observations or initial interpretations of geology or analytical data. It has undergone limited peer review, but does not necessarily conform to DGGS editorial standards. Interpretations or conclusions contained in this publication are subject to change. March 2018 State of Alaska Department of Natural Resources Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys STATE OF ALASKA Bill Walker, Governor DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Andrew T. Mack, Commissioner DIVISION OF GEOLOGICAL & GEOPHYSICAL SURVEYS Steve Masterman, State Geologist & Director Publications produced by the Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys are available for free download from the DGGS website (dggs.alaska.gov). Publications on hard-copy or digital media can be examined or purchased in the Fairbanks office: Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys (DGGS) 3354 College Road | Fairbanks, Alaska 99709-3707 Phone: 907.451.5010 | Fax 907.451.5050 [email protected] | dggs.alaska.gov DGGS publications are also available at: Alaska State Library, Historical Collections & Talking Book Center 395 Whittier Street Juneau, Alaska 99801 Alaska Resource Library and Information Services (ARLIS) 3150 C Street, Suite 100 Anchorage, Alaska 99503 Suggested citation: Mulliken, K.M., Schaefer, J.R., and Cameron, C.E., 2018, Geospatial distribution of tephra fall in Alaska: a geodatabase compilation of published tephra fall occurrences from the Pleistocene to the present: Alaska Division of Geological & Geophysical Surveys Miscellaneous Publication 164, 46 p. -

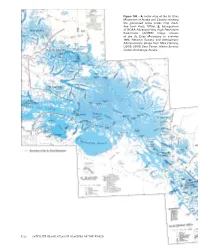

A, Index Map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada Showing the Glacierized Areas (Index Map Modi- Fied from Field, 1975A)

Figure 100.—A, Index map of the St. Elias Mountains of Alaska and Canada showing the glacierized areas (index map modi- fied from Field, 1975a). B, Enlargement of NOAA Advanced Very High Resolution Radiometer (AVHRR) image mosaic of the St. Elias Mountains in summer 1995. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration image from Mike Fleming, USGS, EROS Data Center, Alaska Science Center, Anchorage, Alaska. K122 SATELLITE IMAGE ATLAS OF GLACIERS OF THE WORLD St. Elias Mountains Introduction Much of the St. Elias Mountains, a 750×180-km mountain system, strad- dles the Alaskan-Canadian border, paralleling the coastline of the northern Gulf of Alaska; about two-thirds of the mountain system is located within Alaska (figs. 1, 100). In both Alaska and Canada, this complex system of mountain ranges along their common border is sometimes referred to as the Icefield Ranges. In Canada, the Icefield Ranges extend from the Province of British Columbia into the Yukon Territory. The Alaskan St. Elias Mountains extend northwest from Lynn Canal, Chilkat Inlet, and Chilkat River on the east; to Cross Sound and Icy Strait on the southeast; to the divide between Waxell Ridge and Barkley Ridge and the western end of the Robinson Moun- tains on the southwest; to Juniper Island, the central Bagley Icefield, the eastern wall of the valley of Tana Glacier, and Tana River on the west; and to Chitistone River and White River on the north and northwest. The boundar- ies presented here are different from Orth’s (1967) description. Several of Orth’s descriptions of the limits of adjacent features and the descriptions of the St. -

Workshop on Impacts of Large Volcanic Eruptions on Climate and Societies: Proxies, Models and Solutions for the Future

Workshop on Impacts of large volcanic eruptions on climate and societies: proxies, models and solutions for the future Saas Fee, Switzerland, August 11-15, 2020 Jointly organized by the University of Geneva, Switzerland, Institut Pierre et Simon Laplace (IPSL), France, University of Berne, Switzerland and University of Oslo, Norway Workshop Program and Abstract volume (Abstract are in alphabetical order of author name) Workshop organizers Markus Stoffel Myriam Khodri Michael Sigl Kirstin Krüger 2 Impacts of large volcanic eruptions on climate and societies: Proxies, models and solutions for the future Saas Fee, Switzerland, August 11-15, 2020 WORKSHOP PROGRAM Tuesday, August 11 Afternoon Participants arrive in Saas Fee 18:30 Icebreaker, followed by supper (around 19:30) Wednesday, August 12 09:00-09:10 Welcome by the organizers and meeting objectives. SESSION 1: Volcanic case studies of the Common Era Chairperson: Gary Lynam 09:10-09:30 Samuli Helama, Natural Resources Institute (LUKE), Helsinki, Finland 15 Recurrent transitions to Little Ice Age-like climatic regimes over the Holocene 09:30-09:50 Helen Mackay, Newcastle University, Newcastle, UK Examining potential climatic and societal impacts from the 853 CE Mount Churchill eruption in the North 22 Atlantic region 09:50-10:10 Evelien van Dijk, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway Impact of the 536/540 CE double volcanic eruption event on the 6th-7th century climate using model and 34 proxy data 10:10-10:30 Sébastien Guillet, University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland 14 Climatic and societal