Soundingboard12.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keyboard Sonatas Nos. 87–92 Levon Avagyan, Piano Antonio Soler (1729–1783) Sonatas Included in Op

Antonio SOLER Keyboard Sonatas Nos. 87–92 Levon Avagyan, Piano Antonio Soler (1729–1783) sonatas included in Op. 4 bear the date 1779. These Sonata No. 92 in D major, numbered Op. 4, No. 2, is Keyboard Sonatas Nos. 87–92 sonatas follow classical procedure and are in several again in four movements and in a style that reflects its movements, although some of the movements had prior date, 1779, and contemporary styles and forms of Born in 1729 at Olot, Girona, Antonio Soler, like many Llave de la Modulación, a treatise explaining the art of existence as single-movement works. Sonata No. 91 in C composition, as well as newer developments in keyboard other Catalan musicians of his and later generations, had rapid modulation (‘modulación agitada’), which brought major starts with a movement that has no tempo marking, instruments. The Presto suggests similar influences – the his early musical training as a chorister at the great correspondence with Padre Martini in Bologna, the leading to a second movement, marked Allegro di molto, world of Haydn, Soler’s near contemporary. The third Benedictine monastery of Montserrat, where his teachers leading Italian composer and theorist, who vainly sought in which the bass makes considerable use of divided movement brings two minuets, the first Andante largo included the maestro di capilla Benito Esteve and the a portrait of Soler to add to his gallery of leading octaves. There is contrast in a short Andante maestoso, a and the second, which it frames, a sparer Allegro. The organist Benito Valls. Soler studied the work of earlier composers. -

By Chau-Yee Lo

Dramatizing the Harpsichord: The Harpsichord Music of Elliott Carter by Chau-Yee Lo “I regard my scores as scenarios, auditory scenarios, for performers to act out their instruments, dramatizing the players as individuals and partici- pants in the ensemble.”1 Elliott Carter has often stated that this is his creative standpoint, his works from solo to orchestral pieces growing from the dramatic possibilities inherent in the sounds of the instruments. In this article I will investigate how and to what extent this applies to Carter’s harp- sichord music. Carter has written two works for the harpsichord: Sonata for Flute, Oboe, Cello, and Harpsichord was completed in 1952, and Double Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano with Two Chamber Orchestras in 1961. Both commissions were initiated by harpsichordists: the first by Sylvia Marlowe (1908–81) and the Harpsichord Quartet of New York, for whom the Sonata was written, the latter by Ralph Kirkpatrick (1911–84), who had been Carter’s fellow student at Harvard. Both works encapsulate a significant development in Carter’s technique of composition, and bear evidence of his changing approach to music in the 1950s. Shortly after completing the Double Concerto Carter started writing down the interval combinations he had frequently been using. This exercise continued and became more systematic over the next two decades, and the result is now published as the Harmony Book.2 Carter came to write for the harpsichord for the first time in the Sonata. Here the harpsichord is the only soloist, the other instruments being used as a frame. In particular Carter emphasizes the wide range of tone colours available on the modern harpsichord, echoing these in the different musi- cal characters of the other instruments. -

June 29 to July 5.Txt

CLASSIC CHOICES June 29 - July 5, 2020 PLAY DATE : Mon, 06/29/2020 6:02 AM Antonio Vivaldi Violin Concerto 6:11 AM Johann Nepomuk Hummel Serenade for Winds 6:31 AM Johan Helmich Roman Concerto for Violin and Strings 6:46 AM Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach Symphony 7:02 AM Johann Georg Pisendel Concerto forViolin,Oboes,Horns & Strings 7:16 AM Franz Joseph Haydn Piano Sonata No. 32 7:30 AM Jean-Marie Leclair Violin Concerto 7:48 AM Antonio Salieri La Veneziana (Chamber Symphony) 8:02 AM Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber Mensa sonora, Part III 8:12 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Symphony No. 34 8:36 AM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. 3 9:05 AM Leroy Anderson Concerto for piano and orchestra 9:25 AM Arthur Foote Piano Quartet 9:54 AM Leroy Anderson Syncopated Clock 10:00 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Requiem: Communio: Lux aeterna 10:06 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Violin Sonata No. 21, K 304/300c 10:23 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart DON GIOVANNI Selections 10:37 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart Sonata for 2 pianos 10:59 AM Felix Mendelssohn String Quartet No. 3 11:36 AM Mauro Giuliani Guitar Concerto No. 1 12:00 PM Danny Elfman A Brass Thing 12:10 PM Johann Strauss, Jr. Schwärmereien Concert Waltz 12:23 PM Franz Liszt Un Sospiro (A Sigh) 12:32 PM George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue 12:48 PM John Philip Sousa Our Flirtations 1:00 PM Ludwig Van Beethoven Symphony No. 6 1:43 PM Michael Kurek Sonata for Viola and Harp 2:01 PM Paul Dukas La plainte, au loin, du faune...(The 2:07 PM Leos Janacek Sinfonietta 2:33 PM Johannes Brahms Violin Sonata No. -

La Formació Musical Del Pare Antoni Soler · a Montserrat

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Revistes Catalanes amb Accés Obert LA FORMACIÓ MUSICAL DEL PARE ANTONI SOLER · A MONTSERRAT Gregori Estrada 85 El nom del pare Antoni Soler és ben conegut en el món musical d'avui. La difusió de la seva obra, difusió feta a través d'edicions, audicions i discos, presenta primordialment peces del repertori instrumental. No es pot dir encara que la figura d'Antoni Soler com a compositor sigui prou coneguda. la seva obra instrumental conservada i catalogada fins ara, és probablement inco11Jpleta. A més, Soler té una altra creació, la coral , que sobrepassa en el doble la quantitat de la instrumental. D'aquesta producció coral, avui només se n'han divulgat algunes peces, massa poques per poder-ne fer Un judici raonable. S'ha d'esperar que, amb els anys, el treball pacient dels investiga dors vagi posant en partitura intel·ligible les particel·les de cada una de les composicions corals sortides de la ploma d'Antoni Soler. El treball dels inves tigadors farà també possible una millor apreciació de l'obra de Soler a través de la interpretació viva de la seva música coral. Partitura i interpretació viva, dues condicions necessàries per poder aprofundir en el judici i la crítica dè l'obra de qualsevol compositor L'OBRA MUSICAL D'ANTONI SOLER L'obra musical del pare Soler és copiosa, cosa sorprenent si és té en compte que ell va morir prematurament als 54 anys. Com ja s'ha dit, la seva obra és coneguda sobretot en la part instrumental: més d'un centenar de Sonates per a instrument de tecla; algunes peces per a orgue; sis Concerts per a dos orgues; i sis Quintets per a corda i tecla. -

Grado Medio Prueba De Selección Piano 1º Curso

GRADO MEDIO PRUEBA DE SELECCIÓN PIANO 1º CURSO 1. EJERCICIOS TÉCNICOS. • 6 escalas y arpegios, en tonalidad mayor o/y menor 2. EJERCICIO DE LECTURA 1º VISTA. 3. OBRAS ORIENTATIVAS 1º CURSO. A) COMPOSITORES BARROCOS J. S. BACH Album Anna Magdalena Bach (Clavierbüchlein der Anna Magdalena Bach) Wiener Urtex Edition (editado por Naoyuki Taneda). Minueto en Sol BWV Anh.126 (Compositor desconocido) Marcha en Re BWV Anh. 122 (C. P. E. Bach) Polonesa en sol BWV Ahn. 125 (C. P. E. Bach) Marcha en Mi bemol BWV Ahn. 127 (C. P. E. Bach) Polonesa en Sol BWV Anh. 130 (J. A. Hasse) Apéndice: Suite de Clavecin en Sol (Christian Petzold) Pequeños Preludios: BWV 924, 926, 927, 930, 941, 942, 999, 933, 934. Invenciones: BWV 772 – 786, por ejemplo: No. 1 en Do, No. 4 en re. LOUIS CLAUDE DAQUIN Piezas para teclado Le Coucou (Rondeau) L ´Amusante (Rondeau) Mussette en Sol G. F. HÄNDEL Piezas para teclado. Aria en Sol HWV 441 Entrée en sol HWV 453.II (HHA IV/6) Lesson en la HWV 496 (HHA III/19) Minueto en sol HWV 434.IV (HHA II/1.4) Preludio en re HWV 564 (HHA IV/8) Toccata en sol HWV 586 (HHA IV/20) 1 1º CURSO HENRY PURCELL Piezas para teclado A Choice Collection of Lessons for the harpsichord or spinnet: Suites and Miscellaneuos : Una pieza que corresponda en extension mínima una página. JEAN PHILLIPE RAMEAU Pièces de Clavecin (1724) Tambourin (Rondeau) (de la Suite No. 2) La Villageoise (de la Suite No. 2) La Joyeuse (de la Suite No. -

Vincent Persichetti's Ten Sonatas for Harpsichord

STYLE AND COMPOSITIONAL TECHNIQUES IN VINCENT PERSICHETTI’S TEN SONATAS FOR HARPSICHORD A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE DOCTOR OF ARTS BY MIRABELLA ANCA MINUT DISSERTATION ADVISORS: KIRBY KORIATH AND MICHAEL ORAVITZ BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2009 ii Copyright © 2009 by Mirabella Anca Minut All rights reserved Music examples used in this dissertation comply with Section 107, Fair Use, of the Copyright Law, Title 17 of the United States Code. Sonata for Harpsichord, Op. 52 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1973, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Second Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 146 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1983, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Third Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 149 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1983, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Fourth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 151 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1983, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Fifth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 152 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1984, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Sixth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 154 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1977, 1984 Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Seventh Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 156 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1985, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Eighth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 158 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1987, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Ninth Harpsichord Sonata, Op. 163 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1987, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. Tenth Harpsichord Sonata, [Op. 167] by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1994, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. First String Quartet, Op. 7 by Vincent Persichetti © Copyright 1977, Elkan-Vogel, Inc. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my doctoral committee members, Dr. Kirby Koriath, Dr. Michael Oravitz, Dr. Robert Palmer, Dr. Raymond Kilburn, and Dr. Annette Leitze, as well as former committee member Dr. -

The Harpsichord: a Research and Information Guide

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Illinois Digital Environment for Access to Learning and Scholarship Repository THE HARPSICHORD: A RESEARCH AND INFORMATION GUIDE BY SONIA M. LEE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2012 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch, Chair and Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus Donald W. Krummel, Co-Director of Research Professor Emeritus John W. Hill Associate Professor Emerita Heidi Von Gunden ABSTRACT This study is an annotated bibliography of selected literature on harpsichord studies published before 2011. It is intended to serve as a guide and as a reference manual for anyone researching the harpsichord or harpsichord related topics, including harpsichord making and maintenance, historical and contemporary harpsichord repertoire, as well as performance practice. This guide is not meant to be comprehensive, but rather to provide a user-friendly resource on the subject. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my dissertation advisers Professor Charlotte Mattax Moersch and Professor Donald W. Krummel for their tremendous help on this project. My gratitude also goes to the other members of my committee, Professor John W. Hill and Professor Heidi Von Gunden, who shared with me their knowledge and wisdom. I am extremely thankful to the librarians and staff of the University of Illinois Library System for assisting me in obtaining obscure and rare publications from numerous libraries and archives throughout the United States and abroad. -

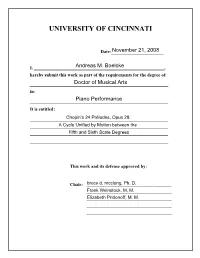

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ Chopin’s 24 Préludes, Opus 28: A Cycle Unified by Motion between the Fifth and Sixth Scale Degrees A document submitted to the The Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2008 by Andreas Boelcke B.A., Missouri Western State University in Saint Joseph, 2002 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 2005 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ii ABSTRACT Chopin’s twenty-four Préludes, Op. 28 stand out as revolutionary in history, for they are neither introductions to fugues, nor etude-like exercises as those preludes by other early nineteenth-century composers such as Johann Nepomuk Hummel, Johan Baptist Cramer, Friedrich Kalkbrenner, and Muzio Clementi. Instead they are the first instance of piano preludes as independent character pieces. This study shows, however, that Op. 28 is not just the beginning of the Romantic prelude tradition but forms a coherent large-scale composition unified by motion between the fifths and sixth scale degrees. After an overview of the compositional origins of Chopin’s Op. 28 and an outline of the history of keyboard preludes, the set will be compared to the contemporaneous ones by Hummel, Clementi, and Kalbrenner. The following chapter discusses previous theories of coherence in Chopin’s Préludes, including those by Jósef M. -

'The British Harpsichord Society' April 2021

ISSUE No. 16 Published by ‘The British Harpsichord Society’ April 2021 ________________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION 1 A word from our Guest Editor - Dr CHRISTOPHER D. LEWIS 2 FEATURES • Recording at Home during Covid 19 REBECCA PECHEFSKY 4 • Celebrating Johann Christoph Friedrich Bach COREY JAMASON 8 • Summer School, Dartington 2021 JANE CHAPMAN 14 • A Review; Zoji PAMELA NASH 19 • Early Keyboard Duets FRANCIS KNIGHTS 21 • Musings on being a Harpsichordist without Gigs JONATHAN SALZEDO 34 • Me and my Harpsichord; a Romance in Three Acts ANDREW WATSON 39 • The Art of Illusion ANDREW WILSON-DICKSON 46 • Real-time Continuo Collaboration BRADLEY LEHMAN 51 • 1960s a la 1760s PAUL AYRES 55 • Project ‘Issoudun 1648-2023’ CLAVECIN EN FRANCE 60 IN MEMORIAM • John Donald Henry (1945 – 2020) NICHOLAS LANE with 63 friends and colleagues ANNOUNCEMENTS 88 • Competitions, Conferences & Courses Please keep sending your contributions to [email protected] Please note that opinions voiced here are those of the individual authors and not necessarily those of the BHS. All material remains the copyright of the individual authors and may not be reproduced without their express permission. INTRODUCTION ••• Welcome to Sounding Board No.16 ••• Our thanks to Dr Christopher Lewis for agreeing to be our Guest Editor for this edition, especially at such a difficult time when the demands of University teaching became even more complex and time consuming. Indeed, it has been a challenging year for all musicians but ever resourceful, they have found creative ways to overcome the problems imposed by the Covid restrictions. Our thanks too to all our contributors who share with us such fascinating accounts of their musical activities during lock-down. -

Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805): an Italian in Madrid

Luigi Boccherini (1743-1805): an italian in Madrid Juan y José PLA Triosonata en Re menor - Allegro (molto) - Andante - Allegro (assai) Danzas cortesanas: Minué, Amable y Contradanzas A. SOLER (1729-1783) Sonata en Re bemol Mayor El Olé de la Curra Seguidillas Boleras P. ESTEVE (ca. 1730-ca. 1794) Jota. (“La murciana en la carcel”, 1776) D. SCARLATTI (1685-1757) Bolero. (Sonata en Mi M, K380) L. BOCCHERINI (1743-1805) Fandango. (Del “Quintetto IV en Re M”) L. BOCCHERINI Quintettino VI, Op. 30. “La musica nocturna delle strade di Madrid” - Ave Maria della Parrocchia. Ave Maria del quartiere - Minuetto dei ciechi - Rosario - Los Manolos - Variazioni sulla Ritirata Nocturna di Madrid PROGRAMME NOTES The spectacle, in homage to the figure of Boccherini, was presented in 2005 by the group of early music and dance, “Los Comediantes del Arte”, to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the composer’s death. It is a genre, called mise en scene, which is not very frequent in Spain but is very popular on the stages of the rest of Europe and is the bringing together of various stage arts such as music, dance and theatre and always based on historical criteria. This work of recuperation requires a meticulous study of documentary sources (scores, dance treatises, engravings, costume designs, etc.) in order to achieve a result which is as faithful as possible to historical reality. Our programme opens with instrumental pieces of authors from the same period, such as the Plá brothers (oboists from Valencia) and father Antonio Soler (famous pupil of Domenico Scarlatti), followed by a selection of original choreographies corresponding to court dances collected in the treatises by Minguet and Ferriol, with obvious French influences. -

1562 ECM 11.2 08-17 1400009-20 Reviews

Eighteenth Century Music http://journals.cambridge.org/ECM Additional services for Eighteenth Century Music: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here ANTONIO ABREU (c1750–c1820), DIONISIO AGUADO (1784–1849), SALVADOR CASTRO DE GISTAU (1770–after 1831), ISIDRO DE LAPORTA (. c1790), FEDERICO MORETTI (c1765–1838) SPANISH MUSIC FOR 6-COURSE GUITAR AROUND 1800 Thomas Schmitt Centaur CRC 3277, 2012; one disc, 66 minutes KENNETH A. HARTDEGEN Eighteenth Century Music / Volume 11 / Issue 02 / September 2014, pp 314 - 316 DOI: 10.1017/S1478570614000207, Published online: 07 August 2014 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S1478570614000207 How to cite this article: KENNETH A. HARTDEGEN (2014). Eighteenth Century Music, 11, pp 314-316 doi:10.1017/ S1478570614000207 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/ECM, IP address: 147.156.157.203 on 27 Aug 2014 reviews written in a galant style and based on the air ‘One evening having lost my way’, which appears in the third act of the opera. This recording succeeds in its intention to explore the neglected repertoire of public concert life in England and in doing so brings to our attention another side to a composer who has been both tarred with the brush of The Beggar’s Opera and maligned by the pen of Hawkins. The accompanying booklet notes, which contain many contemporary anecdotal references as well as an in-depth and well-supported account of the composer’s time in England, give a more balanced account of the reception of Pepusch’s works. -

Music in the Classical Era (Mus 7754)

MUSIC IN THE CLASSICAL ERA (MUS 7754) LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC & DRAMATIC ARTS FALL 2016 instructor Dr. Blake Howe ([email protected]) M&DA 274 meetings Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, 9:30–10:20 M&DA 221 office hours Fridays, 8:30–9:30, or by appointment prerequisite Students must have passed either the Music History Diagnostic Exam or MUS 3710. Howe / MUS 7754 Syllabus / 2 GENERAL INFORMATION COURSE OBJECTIVES This course pursues the diversity of musical life in the eighteenth century, examining the styles, genres, forms, and performance practices that have retrospectively been labeled “Classical.” We consider the epicenter of this era to be the mid eighteenth century (1720–60), with the early eighteenth century as its most logical antecedent, and the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century as its profound consequent. Our focus is on the interaction of French, Italian, and Viennese musical traditions, but our journey will also include detours to Spain and England. Among the core themes of our history are • the conflict between, and occasional synthesis of, French and Italian styles (or, rather, what those styles came to symbolize) • the increasing independence of instrumental music (symphony, keyboard and accompanied sonata, concerto) and its incorporation of galant and empfindsam styles • the expansion and dramatization of binary forms, eventually resulting in what will later be termed “sonata form” • signs of wit, subjectivity, and the sublime in music of the “First Viennese Modernism” (Haydn, Mozart, early Beethoven). We will seek new critical and analytical readings of well-known composers from this period (Beethoven, Gluck, Haydn, Mozart, Pergolesi, Scarlatti) and introduce ourselves to the music of some lesser-known figures (Alberti, Boccherini, Bologne, Cherubini, Dussek, Galuppi, Gossec, Hasse, Hiller, Hopkinson, Jommelli, Piccinni, Rousseau, Sammartini, Schobert, Soler, Stamitz, Vanhal, and Vinci, plus at least two of J.