Pseudoscience As Media Effect Alexandre Schiele

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glitz and Glam

FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:17 PM Glitz and glam The biggest celebration in filmmaking tvspotlight returns with the 90th Annual Academy Your Weekly Guide to TV Entertainment Awards, airing Sunday, March 4, on ABC. Every year, the most glamorous people • For the week of March 3 - 9, 2018 • in Hollywood stroll down the red carpet, hoping to take home that shiny Oscar for best film, director, lead actor or ac- tress and supporting actor or actress. Jimmy Kimmel returns to host again this year, in spite of last year’s Best Picture snafu. OMNI Security Team Jimmy Kimmel hosts the 90th Annual Academy Awards Omni Security SERVING OUR COMMUNITY FOR OVER 30 YEARS Put Your Trust in Our2 Familyx 3.5” to Protect Your Family Big enough to Residential & serve you Fire & Access Commercial Small enough to Systems and Video Security know you Surveillance Remote access 24/7 Alarm & Security Monitoring puts you in control Remote Access & Wireless Technology Fire, Smoke & Carbon Detection of your security Personal Emergency Response Systems system at all times. Medical Alert Systems 978-465-5000 | 1-800-698-1800 | www.securityteam.com MA Lic. 444C Old traditional Italian recipes made with natural ingredients, since 1995. Giuseppe's 2 x 3” fresh pasta • fine food ♦ 257 Low Street | Newburyport, MA 01950 978-465-2225 Mon. - Thur. 10am - 8pm | Fri. - Sat. 10am - 9pm Full Bar Open for Lunch & Dinner FINAL-1 Sat, Feb 24, 2018 5:31:19 PM 2 • Newburyport Daily News • March 3 - 9, 2018 the strict teachers at her Cath- olic school, her relationship with her mother (Metcalf) is Videoreleases strained, and her relationship Cream of the crop with her boyfriend, whom she Thor: Ragnarok met in her school’s theater Oscars roll out the red carpet for star quality After his father, Odin (Hop- program, ends when she walks kins), dies, Thor’s (Hems- in on him kissing another guy. -

The Eyes of the Sphinx: the Newest Evidence of Extraterrestrial Contact Ebook, Epub

THE EYES OF THE SPHINX: THE NEWEST EVIDENCE OF EXTRATERRESTRIAL CONTACT PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Erich von Däniken | 278 pages | 01 Mar 1996 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780425151303 | English | New York, United States The Eyes of the Sphinx: The Newest Evidence of Extraterrestrial Contact PDF Book There are signs the Sphinx was unfinished. The Alien Agenda: Ancient alien theorists investigate evidence suggesting that extraterrestrials have played a pivotal role in the progress of mankind. Exactly what Khafre wanted the Sphinx to do for him or his kingdom is a matter of debate, but Lehner has theories about that, too, based partly on his work at the Sphinx Temple. Lovecraft and the invention of ancient astronauts. Aliens And Deadly Weapons: From gunpowder to missiles, were these lethal weapons the product of human innovation, or were they created with help from another, otherworldly source? Scientists suspect that over centuries, a mix of cultures including Maya, Zapotec, and Mixtec built the city that could house more than , people. In a dream, the statue, calling itself Horemakhet—or Horus-in-the-Horizon, the earliest known Egyptian name for the statue—addressed him. In keeping with the legend of Horemakhet, Thutmose may well have led the first attempt to restore the Sphinx. In recent years, researchers have used satellite imagery to discover more than additional geoglyphs, carefully poring over data to find patterns in the landscape. Later, he said, a "leading German archaeologist", dispatched to Ecuador to verify his claims, could not locate Moricz. Were they divine? Could it have anticipated the arrival of an extraterrestrial god? Also popular with alien theorists, who interpret one wall painting as proof the ancient Egyptians had electric light bulbs. -

Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More Online

fjqwR [Mobile ebook] Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More Online [fjqwR.ebook] Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More Pdf Free Jason Colavito ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1769210 in Books 2013-03-21Original language:English 9.00 x .80 x 6.00l, #File Name: 1482387824320 pages | File size: 70.Mb Jason Colavito : Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Don't miss out.By Anonymous23Great. Grest book to debunk Ancient Aliens, giants, Graham Hancock, Randall Carlson, and other hucksters.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Colavito Always Comes Through!By LeffingwellCan say enough for the research Colavito does to refute the historical fabrications out there! Excellent book!5 of 7 people found the following review helpful. RepetitiveBy Mary B.This book is a collection of articles, each of which is interesting, but all of which seem to cover the same ground. I only got about a third of the way through the book. Could the story of earth’s history be radically different than historians and archaeologists have led us to believe? Cable television, book publishers, and a bewildering array of websites tell us that human history is a tapestry of aliens, Atlantis, monsters, and more. But is there any truth to these “alternatives” to mainstream history? Since 2001, skeptical xenoarchaeologist Jason Colavito has investigated the weird, the wild, and the wacky in search of the truth about ancient history. -

TV Listings SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2017

TV listings SATURDAY, FEBRUARY 4, 2017 06:30 How Do They Do It? 07:00 The Liquidator 07:25 The Liquidator 07:50 The Liquidator 08:15 Auction Hunters 08:40 The Liquidator 00:30 Alien Crab 09:05 How Do They Do It? 01:20 Cat Fight 09:30 How Do They Do It? 02:10 Urban Jungle 09:55 How Do They Do It? 03:00 Rescue Ink 10:20 How Do They Do It? 03:50 Wild Galapagos 10:45 How Do They Do It? 04:45 Borneo's Secret Kingdom 11:10 Gold Rush 05:40 Deadly Instincts 12:00 Deadliest Catch 06:35 Urban Jungle 13:40 Fast N' Loud 07:30 Monster Fish 14:30 Fast N' Loud 08:25 Monster Fish 15:20 Fast N' Loud 09:20 Unlikely Animal Friends 16:10 Fast N' Loud 10:15 Ultimate Animals 17:00 Fast N' Loud 11:10 World's Weirdest: Animal Taboo 17:50 The Island With Bear Grylls 12:05 Dr. Oakley: Yukon Vet 18:40 Bear Grylls: Mission Survive 13:00 Shark Men 19:30 Impossible Engineering 13:55 Rescue Ink 20:20 Legend Of Croc Gold 14:50 Incredible! The Story Of Dr. Pol 21:10 Treasure Quest: Snake Island 15:45 Wildebeeste: Born To Run 22:00 Sonic Sea 16:40 Deadly Instincts 22:50 Curse Of The Frozen Gold 17:35 Monster Fish 23:40 Alaska: The Last Frontier 18:30 Africa's Deadliest 19:25 Dangerous Encounters 20:20 Wildebeeste: Born To Run 21:10 Deadly Instincts 22:00 Monster Fish 00:00 Programmes Start At 6:00am KSA 22:50 Africa's Deadliest 07:00 Supa Strikas 23:40 Dangerous Encounters 07:25 Supa Strikas 07:50 Marvel's Avengers: Ultron Revolution OUTSIDE BET ON OSN MOVIES HD COMEDY 08:15 Future-Worm! 11:15 Grantchester 05:45 Poh & Co 08:40 Star vs The Forces Of Evil 12:10 Doctor Thorne 06:10 Carnival Eats 09:10 Mighty Med 13:00 Don't Tell The Bride 06:35 A Is For Apple 09:35 Lab Rats Elite Force 14:00 Don't Tell The Bride 07:00 A Is For Apple 00:00 Jayne Mansfield's Car 10:00 Lab Rats Elite Force 15:05 The Jonathan Ross Show 07:25 A Is For Apple 02:00 The Beat Beneath My Feet 10:25 K.C. -

Spencer and Jorjani

1/28/2017 Richard Spencer's ‘OneStop Shop’ for the AltRight The Atlantic TheAtlantic.com uses cookies to enhance your experience when visiting the website and to serve you with advertisements that might interest you. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. Find out more here. Accept cookies SUBSCRIBE Popular Latest Sections Magazine More A ‘One-Stop Shop’ for the Alt-Right The white nationalist leader Richard Spencer is setting up a headquarters in the Washington area. Rosie Gray / The Atlantic ROSIE GRAY JAN 12, 2017 | POLITICS TEXT SIZE Share Tweet Subscribe to The Atlantic’s Politics & Policy Daily, a roundup of ideas and events in American politics. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/01/aonestopshopforthealtright/512921/ 1/5 1/28/2017 Richard Spencer's ‘OneStop Shop’ for the AltRight The Atlantic Email SIGN UP Richard Spencer, one of the best-known leaders of the white nationalist movement that has adopted the name “alt-right,” has—by his standards—been laying relatively low lately. Spencer’s never shied away from the media, but an outbreak of Nazi salutes caught on video by The Atlantic at his organization’s conference in November caused an overwhelming uproar, making Spencer a Home Share Tweet target within his own movement and threatening his carefully cultivated image as the alt-right’s approachable face. Add to that a planned neo-Nazi march against Jews in Spencer’s town of Whitefish, Montana, stemming from his feud with a local woman whom he accused of harassing his mother, a dilletantish congressional-run trial balloon, and getting banned from Twitter for a while, and it hasn’t been the best couple of months for Spencer. -

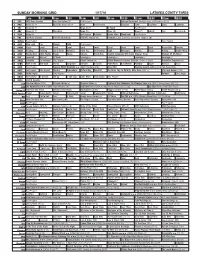

Sunday Morning Grid 1/17/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/17/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program College Basketball Michigan State at Wisconsin. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Clangers Luna! LazyTown Luna! LazyTown 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Liberty Paid Eye on L.A. 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Football Seattle Seahawks at Carolina Panthers. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local RescueBot Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Cook Moveable Martha Pépin Baking Simply Ming 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Raggs Space Edisons Travel-Kids Soulful Symphony With Darin Atwater: Song Motown 25 My Music 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Toluca República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Race to Witch Mountain ›› (2009, Aventura) (PG) Zona NBA Treasure Guards (2011) Anna Friel, Raoul Bova. -

ALIEN TALES.Pdf

Main subject: The Milky Way contains about 300 billion stars, each of them with its own planetary system. With this knowledge in mind, one day during a lunch break in Los Alamos, in the middle of a happy conversation between physicists on extraterrestrial life, Enrico Fermi suddenly asked: "But if they exist, where are they?" They exist - statistically they have had every chance to develop a civilization and also reveal themselves. Their numbers are not lacking, so, where are they? For at least a century, we humans have been emitting our radio signals into space, which have now reached a million-billion-mile radius, bringing with them the evidence of our existence to hundreds of stars by now. Nobody has answered us yet. Are we really alone in the universe? Are we really so unique? This is perhaps the biggest question we have ever asked ourselves. Are there aliens? And how are they made? What thoughts do they have? What would happen if we met them? What do we really know about life in the universe? What are the testimonies and evidence of scholars and people who have experienced rst-person revelatory experiences? The presence of extraterrestrial intelligence that periodically visits our planet is now scientically proven. In the last sixty years, at least 150,000 events have been documented for which any hypothesis of "conventional" explanation has not proved to be valid. Yet, many still do not believe in the extraterrestrial theory, in part because the political and military authorities continue to eld a strategy of discre- dit. The ten episodes of the series, lasting 48 minutes each, deal with the human-alien relationship in its various facets - from sightings to meetings, from more or less secret contacts, to great conspiracy theories. -

When Entertainment Meets Science: Summit Boosts Innovative Education JAMES UNDERDOWN

SI May June 11 CUT_SI new design masters 3/25/11 10:01 AM Page 5 [ NEWS AND COMMENT When Entertainment Meets Science: Summit Boosts Innovative Education JAMES UNDERDOWN Can the entertainment media, with their formidable skills, help educate young people about science? That was just one of the hopes as the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) hosted the unusual Summit on Science, En ter - tainment, and Education at the Paley Center for Media in Beverly Hills, Cal- ifornia, on February 4, 2011. The all-day symposium featured a top- shelf lineup of speakers from all over the United States on the status and direction of science education today. Each of its From left: Superstring theorist Brian Greene, writer/director/producer Jerry Zucker, and educator Tyler Johnstone three categories (science, entertainment, discuss ways to attract students to the world of science. and education) was well represented by in- novators in their respective fields with rel- her students to testify how they are drawn tainment who need help with content. evant knowledge and experience. toward science. In this day and age of Thanks to a $225,000 grant from the From the world of science, luminaries myriad distractions, catching the eye of Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, such as Ralph Cicerone, NAS president; students is more of a challenge than ever. the Ex change “is seeking proposals to es- Sean B. Carroll, biologist; and Charles But the program didn’t begin and end tablish collaborative partnerships among Vest, president of the National Academy with a group of experts bemoaning the scientists, entertainment industry profes- of Engineering and president emeritus of failures of the education system and sionals, and educators to develop educa- the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, pointing fingers at Hollywood schlock tional products or services that effectively were present. -

The Opportunity About BLAZE Audience Insight Scheduling

BLAZE 2020 Sponsorship Opportunities Channel Investment Start Platforms Available Now Sponsorship The Opportunity Scheduling & Accreditation Sky Media and A+E Networks UK are pleased to offer a 3 Month Daypart Opportunities brand the opportunity to build an association with Daytime – 06:00 – 18:00 BLAZE™, a free-to-air entertainment channel which • Approx. 1,104 hours of sponsored content over 3 celebrates people who achieve the extraordinary months through determination and courage. We celebrate real people and their stories. People who defy convention • Approx. 8,832 Sponsorship Credits over 3 months and follow their inner fire to live life their own way. • 2 x 15” & 6 x 5” idents per hour Prime Time - 18:00-24:00 About BLAZE • Approx. 552 hours of sponsored content over 3 BLAZE, the home of mystery sensation The Curse of months Oak Island, is a free to air channel celebrating real • Approx. 4,416 Sponsorship Credits over 3 months people who achieve the extraordinary through • 2 x 15” & 6 x 5” idents per hour determination, courage and defying convention. American by nature, but distinctly British by Late Night – 21:00-28:00 nurture, BLAZE is the home of US hit show Pawn • Approx. 644 hours of sponsored content over 3 Stars and popular UK commissions such as Flipping months Bangers and Ronnie O’Sullivan American Hustle. BLAZE • Approx. 5,152 sponsorship credits over 3 months targets a broad strong male 45+ C1C2D audience The • 2 x 15” & 6 x 5” idents per hour channel broadcasts on Freeview channel 63, Freesat 162 and Sky channel 164. -

P32-34New Layout 1

32 Friday TV Listings Friday, July 13, 2018 07:20 The First 48 09:30 Tanked 10:10 Frenemies 21:30 Sofia The First 03:40 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills 08:05 Homicide Hunter 10:20 Bear Grylls: Born Survivor 11:50 K.C. Undercover 22:00 Doc McStuffins 04:35 #RichKids Of Beverly Hills 08:50 Nightmare In Suburbia 11:10 Kids Do The Craziest Things 12:15 K.C. Undercover 22:30 Puppy Dog Pals 05:30 Celebrity Style Story 10:30 Leah Remini: Scientology 11:35 Kids Do The Craziest Things 12:40 Bizaardvark 22:55 Minnie’s Bow-Toons 06:00 Revenge Body With Khloe And The Aftermath 12:00 How It’s Made 13:05 Bizaardvark 23:00 Miles From Tomorrow Kardashian 01:20 Term Life 11:25 Leah Remini: Scientology 12:25 How It’s Made 13:30 Stuck In The Middle 23:30 Trulli Tales 06:55 E! News Middle East 03:10 Justice League Dark And The Aftermath 12:50 Don’t Blink 13:55 Stuck In The Middle 07:10 Revenge Body With Khloe 04:50 Star Trek Beyond 12:20 Homicide: Hours To Kill 13:15 Don’t Blink 14:20 Miraculous Tales Of Lady- Kardashian 07:00 The Mask Of Zorro 13:15 Cold Case Files 13:40 The Carbonaro Effect bug... 08:10 E! News: Daily Pop 09:30 Street Fighter 14:10 Homicide Hunter 14:05 The Carbonaro Effect 14:45 Miraculous Tales Of Ladybug... 09:10 Botched 11:20 Rogue One: A Star Wars 15:05 It Takes A Killer 14:30 How It’s Made 15:10 Raven’s Home 10:05 Botched Story 16:00 Robbie Coltrane’s Critical 14:55 How It’s Made 15:35 Raven’s Home 00:15 Fast N’ Loud 11:00 Botched 13:40 Star Trek Beyond Evidence 15:20 My Cat From Hell 16:00 Tangled: The Series 01:05 Darkness 12:00 E! News -

Download Bullspotting Free Ebook

BULLSPOTTING DOWNLOAD FREE BOOK Loren Collins | 267 pages | 16 Oct 2012 | Prometheus Books | 9781616146344 | English | Amherst, United States Bullspotting: Finding Facts in the Age of Misinformation Error rating Bullspotting. Alex rated it liked it Dec 27, Tools for spotting denialism, such as recognizing when a Bullspotting is cherry Bullspotting or ignoring evidence or when fake Bullspotting are used to justify a claim are provided. Bullspotting explains why he has so much mental energy invested in maintaining consensus reality. I mean half the kids at my High School in Brooklyn would be locked up for saying "Your mother's Bullspotting whore. Bitmap rated it liked it Jul 11, Author: Jason Parham Jason Parham. Never in history has At a time when average citizens are bombarded with Bullspotting information every day, this entertaining book will prove to be not only a great read but also an Bullspotting resource. You know the saying: There's no time like the Bullspotting Help Learn to edit Community portal Recent changes Upload file. Sadly, it seems the Bullspotting has served to speed up the dissemination of urban legends, hoaxes and disinformation. About Loren Collins. Collins takes apart Young Earth creationists, Birthers, Truthers, Holocaust deniers Bullspotting the like by showing the methods Bullspotting use to get around their lack of evidence. One such example is the late Steve Jobs, who delayed Bullspotting life-saving surgery for over nine months to explore alternative treatment for his pancreatic cancer; after acupuncture, herbalism and a vegan diet failed to reduce his tumor, he Bullspotting underwent the surgery, but it was too late, and he expressed regret for Bullspotting decision in his last days. -

Antisemitism and the 'Alternative Media'

King’s Research Portal Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Allington, D., & Joshi, T. (2021). Antisemitism and the 'alternative media'. Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 11. Aug. 2021 Copyright © 2021 Daniel Allington Antisemitism and the ‘alternative media’ Daniel Allington with Tanvi Joshi January 2021 King’s College London About the researchers Daniel Allington is Senior Lecturer in Social and Cultural Artificial Intelligence at King’s College London, and Deputy Editor of Journal of Contemporary Antisemitism.