Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More Online

fjqwR [Mobile ebook] Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More Online [fjqwR.ebook] Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More Pdf Free Jason Colavito ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1769210 in Books 2013-03-21Original language:English 9.00 x .80 x 6.00l, #File Name: 1482387824320 pages | File size: 70.Mb Jason Colavito : Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Faking History: Essays on Aliens, Atlantis, Monsters, and More: 1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Don't miss out.By Anonymous23Great. Grest book to debunk Ancient Aliens, giants, Graham Hancock, Randall Carlson, and other hucksters.0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Colavito Always Comes Through!By LeffingwellCan say enough for the research Colavito does to refute the historical fabrications out there! Excellent book!5 of 7 people found the following review helpful. RepetitiveBy Mary B.This book is a collection of articles, each of which is interesting, but all of which seem to cover the same ground. I only got about a third of the way through the book. Could the story of earth’s history be radically different than historians and archaeologists have led us to believe? Cable television, book publishers, and a bewildering array of websites tell us that human history is a tapestry of aliens, Atlantis, monsters, and more. But is there any truth to these “alternatives” to mainstream history? Since 2001, skeptical xenoarchaeologist Jason Colavito has investigated the weird, the wild, and the wacky in search of the truth about ancient history. -

Spencer and Jorjani

1/28/2017 Richard Spencer's ‘OneStop Shop’ for the AltRight The Atlantic TheAtlantic.com uses cookies to enhance your experience when visiting the website and to serve you with advertisements that might interest you. By continuing to use this site, you agree to our use of cookies. Find out more here. Accept cookies SUBSCRIBE Popular Latest Sections Magazine More A ‘One-Stop Shop’ for the Alt-Right The white nationalist leader Richard Spencer is setting up a headquarters in the Washington area. Rosie Gray / The Atlantic ROSIE GRAY JAN 12, 2017 | POLITICS TEXT SIZE Share Tweet Subscribe to The Atlantic’s Politics & Policy Daily, a roundup of ideas and events in American politics. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2017/01/aonestopshopforthealtright/512921/ 1/5 1/28/2017 Richard Spencer's ‘OneStop Shop’ for the AltRight The Atlantic Email SIGN UP Richard Spencer, one of the best-known leaders of the white nationalist movement that has adopted the name “alt-right,” has—by his standards—been laying relatively low lately. Spencer’s never shied away from the media, but an outbreak of Nazi salutes caught on video by The Atlantic at his organization’s conference in November caused an overwhelming uproar, making Spencer a Home Share Tweet target within his own movement and threatening his carefully cultivated image as the alt-right’s approachable face. Add to that a planned neo-Nazi march against Jews in Spencer’s town of Whitefish, Montana, stemming from his feud with a local woman whom he accused of harassing his mother, a dilletantish congressional-run trial balloon, and getting banned from Twitter for a while, and it hasn’t been the best couple of months for Spencer. -

ALIEN TALES.Pdf

Main subject: The Milky Way contains about 300 billion stars, each of them with its own planetary system. With this knowledge in mind, one day during a lunch break in Los Alamos, in the middle of a happy conversation between physicists on extraterrestrial life, Enrico Fermi suddenly asked: "But if they exist, where are they?" They exist - statistically they have had every chance to develop a civilization and also reveal themselves. Their numbers are not lacking, so, where are they? For at least a century, we humans have been emitting our radio signals into space, which have now reached a million-billion-mile radius, bringing with them the evidence of our existence to hundreds of stars by now. Nobody has answered us yet. Are we really alone in the universe? Are we really so unique? This is perhaps the biggest question we have ever asked ourselves. Are there aliens? And how are they made? What thoughts do they have? What would happen if we met them? What do we really know about life in the universe? What are the testimonies and evidence of scholars and people who have experienced rst-person revelatory experiences? The presence of extraterrestrial intelligence that periodically visits our planet is now scientically proven. In the last sixty years, at least 150,000 events have been documented for which any hypothesis of "conventional" explanation has not proved to be valid. Yet, many still do not believe in the extraterrestrial theory, in part because the political and military authorities continue to eld a strategy of discre- dit. The ten episodes of the series, lasting 48 minutes each, deal with the human-alien relationship in its various facets - from sightings to meetings, from more or less secret contacts, to great conspiracy theories. -

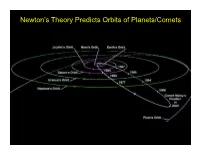

Newton's Theory Predicts Orbits of Planets/Comets

Newton’s Theory Predicts Orbits of Planets/Comets A Problem: Mercury’s Orbit Not Perfect NOT PREDICTED BY NEWTON Prediction: Another Planet – “Vulcan” – inside Mercury’s Orbit NEVER OBSERVED! A New Theory of Gravity: General Relativity Einstein A New Theory of Gravity: General Relativity Mass “warps” spacetime. This is a 2 dimensional analogy Prediction: Einstein’s Theory of Gravity Evidence for General Relativity : Gravitational Lens Is General Relativity the final Theory of Gravity? A Second Example of a Scientific Theory : Evolution Modern Humans and other primates (i.e. Chimpanzees and Gorillas) evolved from a common ancestor several million years ago. Genetic Evidence for Human Evolution: Human Chromosome 2 23 Other primates have 24 pairs of chromosomes but Humans only have 23. How can we be genetically related? The answer: Human chromosome 2 is a fusion of two chromosomes from a common ancestor Pseudoscience Example of Astrology The ancient belief that the Sun, Moon, and the planets affect human behavior and personality Astrology is NOT the same as Astronomy Astrology • Claims to study how the positions of the Sun, Moon, & planets among the stars influence human behavior • Started by Babylonians 1000 BC, was a driving force which advanced ancient astronomy • Kepler & Galileo were the last astronomers to cast horoscopes… since then astronomy grew apart from astrology into a modern science • All modern scientific tests of astrology fail… it is a pseudoscience Astrology (cont) • Is a $200M per year business, in at least 1000 newspapers, with 10,000 practicing astrologers • Uses astronomical information, but has critical and subjective step of interpretation • Has failed many published statistical tests with samples of thousands of people • Failed a famous test by Gauquelin, who found no match of star signs and profession. -

Ancient Astronaut« Narrations

Marburg Journal of Religion: Volume 11, No. 1 (June 2006) »Ancient Astronaut« Narrations A Popular Discourse on Our Religious Past1 Andreas Grünschloß Abstract: In their typical explanatory and unveiling gesture, the narrations about Ancient Astronauts have become a popular myth about our religious past. Nowadays, these narrations are often contained in a specific genre of literature on the alternative bookshelves, and a gigantic theme park in Interlaken (“Mystery Park”) is staging some of its basic ideas. This Ancient Astronaut discourse owes much to Swiss-born Erich von Däniken, to be sure, but it can be traced back to the earlier impact of Charles Fort and his iconoclastic books about “damned data” – anomalistic sightings and findings which an ignorant science deliberately seemed to “exclude”. Since then, the “Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence in Ancient Times” (Paleo-SETI or PSETI) has become a popular “research” subject, leading not only to various publications in many languages of the world, but also to lay-research organizations and conventions. – The paper tries to identify the major themes, motivations and argumentative strategies in the Ancient Astronauts discourse, as well as its typical oscillation between an ‘alternative science’ and manifest esotericism. With its ‘neo-mythic’ activity (ufological Euhemerism, re-enchantment of heaven, foundation myth for modernity, etc.), it resembles a secular and ‘ufological’ parallel to creationism, displaying a strong belief in the ‘hidden’ truth of the religious traditions. This -

Searches for Life and Intelligence Beyond Earth

Technologies of Perception: Searches for Life and Intelligence Beyond Earth by Claire Isabel Webb Bachelor of Arts, cum laude Vassar College, 2010 Submitted to the Program in Science, Technology and Society in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology September 2020 © 2020 Claire Isabel Webb. All Rights Reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _____________________________________________________________ History, Anthropology, and Science, Technology and Society August 24, 2020 Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ David Kaiser Germeshausen Professor of the History of Science (STS) Professor of Physics Thesis Supervisor Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ Stefan Helmreich Elting E. Morison Professor of Anthropology Thesis Committee Member Certified by: ___________________________________________________________________ Sally Haslanger Ford Professor of Philosophy and Women’s and Gender Studies Thesis Committee Member Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________________ Graham Jones Associate Professor of Anthropology Director of Graduate Studies, History, Anthropology, and STS Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________________ -

Extraordinary Encounters: an Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings

EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS An Encyclopedia of Extraterrestrials and Otherworldly Beings Jerome Clark B Santa Barbara, California Denver, Colorado Oxford, England Copyright © 2000 by Jerome Clark All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, except for the inclusion of brief quotations in a review, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Clark, Jerome. Extraordinary encounters : an encyclopedia of extraterrestrials and otherworldly beings / Jerome Clark. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1-57607-249-5 (hardcover : alk. paper)—ISBN 1-57607-379-3 (e-book) 1. Human-alien encounters—Encyclopedias. I. Title. BF2050.C57 2000 001.942'03—dc21 00-011350 CIP 0605040302010010987654321 ABC-CLIO, Inc. 130 Cremona Drive, P.O. Box 1911 Santa Barbara, California 93116-1911 This book is printed on acid-free paper I. Manufactured in the United States of America. To Dakota Dave Hull and John Sherman, for the many years of friendship, laughs, and—always—good music Contents Introduction, xi EXTRAORDINARY ENCOUNTERS: AN ENCYCLOPEDIA OF EXTRATERRESTRIALS AND OTHERWORLDLY BEINGS A, 1 Angel of the Dark, 22 Abductions by UFOs, 1 Angelucci, Orfeo (1912–1993), 22 Abraham, 7 Anoah, 23 Abram, 7 Anthon, 24 Adama, 7 Antron, 24 Adamski, George (1891–1965), 8 Anunnaki, 24 Aenstrians, 10 Apol, Mr., 25 -

The Ufo Enigma 21R2 Oirs Crscir2 Crs Crsoirs

CR C S UG 633 76-52 SP THE UFO ENIGMA 21R2 OIRS CRSCIR2 CRS CRSOIRS MAR CIA S. SMITH Analyst in Science and Technology Science Policy Research Division March 9, 1976 CONGRESSIONAL RESEARCH SERVICE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CR _ t' TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction 1 What is a UFO? 2 A. Definitions 2 B. Drawings by Witnesses 5 C. Types of Encounters 10 II. Witness Credibility 15 A. Sociological and Psychological Factors 15 B. Other Limitations on Witnesses 21 C. Strangeness-Probability Curve 24 III. Point - Counterpoint 25 A. Probable Invalidity of the Extraterrestrial Hypothesis 26 B. Alleged Air Force Secrecy and Cover Ups 29 C. Hoaxes and Witness Credibility 31 D. Possible Benefits to Science From a UFO Study 34 IV. Pre-1947 Accounts 37 A. Biblical Sightings 37 B. Other Early Reports 38 C. The Wave of 1896 41 D. The Post-War European Wave 44 V. 1947-1969 Accounts and Activities 46 A. United States 46 1. Kenneth Arnold and the 1947 Wave 46 2. U. S. Air Force Involvement (1948-1969) 48 a. Projects Sign and Grudge (1948-1952) 49 b. The Robertson Panel and Project Blue Book (1952-1953) 53 c. Special Report #14 and the O'Brien Report: Project Blue Book (1953-1966) 56 d. The Condon Report and Termination of USAF Interest (1967-1969) 63 3. Congressional Interest 69 a. House Armed Services Committee Hearings (1966) 69 b. House Science and Astronautics Committee Hearings (1968) 72 4. Private Organizations 80 a. APRO 81 b. NICAP 82 c. CUFOS 83 d. MUFON 84 e. -

Ufos and Alien Visits According to Polls, About a Third of Americans

UFOs and Alien Visits According to polls, about a third of Americans believe that we are being visited by flying saucers. If so, this would be profoundly important, since it would prove the existence of not just life, but technologically superior intelligent life. What is the evidence for this? In a larger sense, how much evidence should we demand to believe in alien visits? In this class we will go over the evidence and the psychology of belief. The net conclusion from my standpoint is that there is not a shred of definitive evidence for alien visits now or in the past, but that this demonstrates the eagerness people have to believe fun things :). Levels of belief and the burden of proof We will start by discussing several levels of belief, and how they apply to assessment of evidence. Levels include: • True believer. The phenomenon in question has been established beyond any possible doubt, and no further data or disproof of apparent evidence will make a difference. • Hopeful believer. Willing to accept disproof in individual cases, but still has a firm belief in the overall phenomenon. Consider Cubs fans, who are disappointed year after year but still believe starting the next season. • Genuinely neutral. Has not made up mind yet, and thinks that arguments for or against a phenomenon are about equally strong. Alternatively, has simply not cared enough to make a judgment. • Persuadable skeptic. Thinks that no current evidence for the phenomenon is enough for belief, but if strong enough evidence is presented they can accept it. • Entrenched skeptic. -

Ufo Investigations in Cold War America, 1947-1977 Kate Dorsch University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Reliable Witnesses, Crackpot Science: Ufo Investigations In Cold War America, 1947-1977 Kate Dorsch University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Dorsch, Kate, "Reliable Witnesses, Crackpot Science: Ufo Investigations In Cold War America, 1947-1977" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3231. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3231 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3231 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Reliable Witnesses, Crackpot Science: Ufo Investigations In Cold War America, 1947-1977 Abstract This dissertation explores efforts to design and execute scientific tuds ies of unidentified flying objects (UFOs) in the United States in the midst of the Cold War as a means of examining knowledge creation and the construction of scientific uthora ity and credibility around controversial subjects. I begin by placing officially- sanctioned, federally-funded UFO studies in their appropriate context as a Cold War national security project, specifically a project of surveillance and observation, built on traditional arrangements within the military- industrial-academic complex. I then show how non-traditional elements of the investigations – the reliance on non-expert witnesses to report transient phenomena – created space for dissent, both within the scientific establishment and among the broader American public. By placing this dissent within the larger social and political instability of the mid-20th century, this dissertation highlights the deep ties between scientific knowledge production and the social value and valence of professional expertise, as well as the power of experiential expertise in challenging formal, hegemonic institutions. -

Upk Bullard Pback Frontmatterrev2.Indd

© University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Contents Acknowledgments vii Preface to the Paperback Edition ix List of Abbreviations xxiii Introduction: A Mystery of Mythic Proportions 1 1 Who Goes There? The Myth and the Mystery of UFOs 25 2 The Growth and Evolution of UFO Mythology 52 3 UFOs of the Past 97 4 From the Otherworld to Other Worlds 124 5 The Space Children: A Case Example 176 6 Secret Worlds and Promised Lands 201 7 Other Than Ourselves 229 8 Explaining UFOs: An Inward Look 252 9 Explaining UFOs: Something Yet Remains 286 Appendix: UFO-Related Web Sites 315 Notes 319 Select Bibliography 375 Index 399 An illustration section follows page 165 © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Mary Castner, Mark Rodeghier, and Michael D. Swords for CUFOS, James Carrion for MUFON, Phyllis Galde for Fate magazine, Janet Bord for the Fortean Picture Library, and Richard F. Haines, whose help in providing illustrations for this book is greatly appreciated. I owe especial thanks to Jerome Clark and David M. Jacobs for reading the manu- script and devoting efforts above and beyond the call of duty to whip my unruly writ- ing into shape. A final thank-you goes to my long-suffering editor, Michael J. Briggs, who had to wait far too long for me to finish, but who did so with patience and always a helping hand. -

Horoscopes Versus Telescopes: a Focus on Astrology

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 11 - Fall 1988 © 1988, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112 Horoscopes Versus Telescopes: A Focus on Astrology A Note from the Editor: The revelation in 1988 that First Lady Nancy Reagan consulted a San Francisco astrologer in arranging the president's schedule may have surprised or amused many teachers and parents who pay little attention to this old superstition. Unfortunately, belief in the power of astrology is much more widespread among our students than many people realize. A 1984 Gallup Poll indicated that 55% of American teenagers believe that astrology works. Astrology columns appear in over 1200 newspapers in the US; by contrast, fewer than 10 newspapers have columns on astronomy. And all around the world, people base personal, financial, and even medical decisions on the advice of astrologers. Furthermore, astrology is only one of a number of pseudo-scientific beliefs whose uncritical acceptance by the media and the public has contributed to a disturbing lack of skepticism among youngsters (and, apparently, presidents) in the U.S. Many teachers feel that it is beneath our dignity to address topics like this in our courses or periods on science. Unfortunately, by failing to encourage healthy doubt and critical thinking in our children, we may be raising a generation that is willing to believe just about any far-fetched claim printed in the newspapers or reported on television. We therefore devote this issue of The Universe in the Classroom to information about debunking astrology and using student interest in such "fiction sciences'' to help encourage critical thinking and illustrate the use of the scientific method.