Copyright by Shantel Gabrieal Buggs 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

“I Woke up to the World”: Politicizing Blackness and Multiracial Identity Through Activism

“I woke up to the world”: Politicizing Blackness and Multiracial Identity Through Activism by Angelica Celeste Loblack A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Sociology College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Elizabeth Hordge-Freeman, Ph.D. Beatriz Padilla, Ph.D. Jennifer Sims, Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 3, 2020 Keywords: family, higher education, involvement, racialization, racial socialization Copyright © 2020, Angelica Celeste Loblack TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ............................................................................................................................ iii Abstract ..................................................................................................................................... iv Introduction: Falling in Love with my Blackness ........................................................................ 1 Black while Multiracial: Mapping Coalitions and Divisions ............................................ 5 Chapter One: Literature Review .................................................................................................. 8 Multiracial Utopianism: (Multi)racialization in a Colorblind Era ..................................... 8 I Am, Because: Multiracial Pre-College Racial Socialization ......................................... 11 The Blacker the Berry: Racialization and Racial Fluidity ............................................... 15 Racialized Bodies: (Mono)racism -

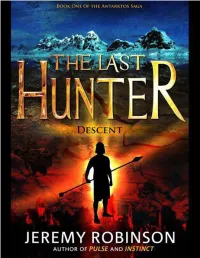

THE LAST HUNTER by Jeremy Robinson

THE LAST HUNTER By Jeremy Robinson OTHER NOVELS by JEREMY ROBINSON Threshold (coming in 2011) Instinct Pulse Kronos Antarktos Rising Beneath Raising the Past The Didymus Contingency PRAISE FOR WORKS OF JEREMY ROBINSON Skip front-matter to table of contents "Rocket-boosted action, brilliant speculation, and the recreation of a horror out of the mythologic past, all seamlessly blend into a rollercoaster ride of suspense and adventure." -- James Rollins, New York Times bestselling author of JAKE RANSOM AND THE SKULL KING'S SHADOW "With THRESHOLD Jeremy Robinson goes pedal to the metal into very dark territory. Fast-paced, action- packed and wonderfully creepy! Highly recommended!" --Jonathan Maberry, NY Times bestselling author of ROT & RUIN "Jeremy Robinson is the next James Rollins" -- Chris Kuzneski, NY Times bestselling author of THE SECRET CROWN "If you like thrillers original, unpredictable and chock-full of action, you are going to love Jeremy Robinson..."- - Stephen Coonts, NY Times bestselling author of DEEP BLACK: ARCTIC GOLD "How do you find an original story idea in the crowded action-thriller genre? Two words: Jeremy Robinson." -- Scott Sigler, NY Times Bestselling author of ANCESTOR "There's nothing timid about Robinson as he drops his readers off the cliff without a parachute and somehow manages to catch us an inch or two from doom." -- Jeff Long, New York Times bestselling author of THE DESCENT "Greek myth and biotechnology collide in Robinson's first in a new thriller series to feature the Chess Team... Robinson will have readers turning the pages..." -- Publisher's Weekly "Jeremy Robinson’s THRESHOLD is one hell of a thriller, wildly imaginative and diabolical, which combines ancient legends and modern science into a non-stop action ride that will keep you turning the pages until the wee hours. -

Reconsidering the Relationship Between New Mestizaje and New Multiraciality As Mixed-Race Identity Models1

Reconsidering the Relationship Between New Mestizaje and New Multiraciality as Mixed-Race Identity Models1 Jessie D. Turner Introduction Approximately one quarter of Mexican Americans marry someone of a different race or ethnicity— which was true even in 1963 in Los Angeles County—with one study finding that 38 percent of fourth- generation and higher respondents were intermarried.1 It becomes crucial, therefore, to consider where the children of these unions, a significant portion of the United States Mexican-descent population,2 fit within current ethnoracial paradigms. As such, both Chicana/o studies and multiracial studies theorize mixed identities, yet the literatures as a whole remain, for the most part, non-conversant with each other. Chicana/o studies addresses racial and cultural mixture through discourses of (new) mestizaje, while multiracial studies employs the language of (new) multiraciality.3 Research on the multiracially identified population focuses primarily on people of African American and Asian American, rather than Mexican American, backgrounds, whereas theories of mestizaje do not specifically address (first- and second- generation) multiracial experiences. In fact, when I discuss having parents and grandparents of different races, I am often asked by Chicana/o studies scholars, “Why are you talking about being multiracial as if it were different from being mestiza/o? Both are mixed-race experiences.” With the limitations of both fields in mind, I argue that entering these new mixed-identity discourses into conversation through an examination of both their significant parallels and divergences accomplishes two goals. First, it allows for a more complete acknowledgement and understanding of the unique nature of multiracial Mexican-descent experiences. -

Afro-Latinx Transnational Identities: Adults in the San Francisco Bay and Los Angeles Area Koby Heramil [email protected]

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Master's Theses Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects Fall 12-15-2017 Afro-Latinx Transnational Identities: Adults in the San Francisco Bay and Los Angeles Area Koby Heramil [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/thes Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Heramil, Koby, "Afro-Latinx Transnational Identities: Adults in the San Francisco Bay and Los Angeles Area" (2017). Master's Theses. 262. https://repository.usfca.edu/thes/262 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, Capstones and Projects at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Afro-Latinx Transnational Identities: Adults in the San Francisco Bay and Los Angeles Area Koby Heramil University of San Francisco November 2017 Master of Arts in International Studies Afro-Latinx Transnational Identities: Adults in the San Francisco Bay and Los Angeles Area In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree MASTER OF ARTS in INTERNATIONAL STUDIES by Koby Heramil November 21, 2017 UNIVERSITY OF SAN FRANCISCO Under the guidance and approval of the committee, and approval by all the members, this thesis project has been accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree. APPROVED: Adviser Date 12-21-2017 ________________________________________ ________________________ Academic Director Date ________________________________________ ________________________ !ii Nomenclature (For this study) 1. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

How Ninja from Die Antwoord Performs South African White Masculinities Through the Digital Archive

ZEF AS PERFORMANCE ART ON THE ‘INTERWEB’: How Ninja from Die Antwoord performs South African white masculinities through the digital archive by Esther Alet Rossouw Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM in the Department of Drama Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Supervisor: Dr M Taub AUGUST 2015 1 ABSTRACT The experience of South African rap-rave group Die Antwoord’s digital archive of online videos is one that, in this study, is interpreted as performance art. This interpretation provides a reading of the character Ninja as a performance of South African white masculinities, which places Die Antwoord’s work within identity discourse. The resurgence of the discussion and practice of performance art in the past thirty years has led some observers to suggest that Die Antwoord’s questionable work may be performance art. This study investigates a reconfiguration of the notion of performance art in online video. This is done through an interrogation of notions of risk, a conceptual dimension of ideas, audience participation and digital liveness. The character Ninja performs notions of South African white masculinities in their music videos, interviews and short film Umshini Wam which raises questions of representation. Based on the critical reading of Die Antwoord’s online video performance art, this dissertation explores notions of Zef, freakery, the abject, new ethnicities, and racechanges, as related to the research field of whiteness, to interpret Ninja’s performance of whiteness. A gendered reading of Die Antwoord’s digital archive is used to determine how hegemonic masculinities are performed by Ninja. It is determined that through their parodic performance art, Die Antwoord creates a transformative intervention through which stagnant notions of South African white masculinity may be reconfigured. -

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017

The Top 7000+ Pop Songs of All-Time 1900-2017 Researched, compiled, and calculated by Lance Mangham Contents • Sources • The Top 100 of All-Time • The Top 100 of Each Year (2017-1956) • The Top 50 of 1955 • The Top 40 of 1954 • The Top 20 of Each Year (1953-1930) • The Top 10 of Each Year (1929-1900) SOURCES FOR YEARLY RANKINGS iHeart Radio Top 50 2018 AT 40 (Vince revision) 1989-1970 Billboard AC 2018 Record World/Music Vendor Billboard Adult Pop Songs 2018 (Barry Kowal) 1981-1955 AT 40 (Barry Kowal) 2018-2009 WABC 1981-1961 Hits 1 2018-2017 Randy Price (Billboard/Cashbox) 1979-1970 Billboard Pop Songs 2018-2008 Ranking the 70s 1979-1970 Billboard Radio Songs 2018-2006 Record World 1979-1970 Mediabase Hot AC 2018-2006 Billboard Top 40 (Barry Kowal) 1969-1955 Mediabase AC 2018-2006 Ranking the 60s 1969-1960 Pop Radio Top 20 HAC 2018-2005 Great American Songbook 1969-1968, Mediabase Top 40 2018-2000 1961-1940 American Top 40 2018-1998 The Elvis Era 1963-1956 Rock On The Net 2018-1980 Gilbert & Theroux 1963-1956 Pop Radio Top 20 2018-1941 Hit Parade 1955-1954 Mediabase Powerplay 2017-2016 Billboard Disc Jockey 1953-1950, Apple Top Selling Songs 2017-2016 1948-1947 Mediabase Big Picture 2017-2015 Billboard Jukebox 1953-1949 Radio & Records (Barry Kowal) 2008-1974 Billboard Sales 1953-1946 TSort 2008-1900 Cashbox (Barry Kowal) 1953-1945 Radio & Records CHR/T40/Pop 2007-2001, Hit Parade (Barry Kowal) 1953-1935 1995-1974 Billboard Disc Jockey (BK) 1949, Radio & Records Hot AC 2005-1996 1946-1945 Radio & Records AC 2005-1996 Billboard Jukebox -

AWARDS 21X MULTI-PLATINUM ALBUM May // 5/1/18 - 5/31/18

RIAA GOLD & PLATINUM HOOTIE & THE BLOWFISH // CRACKED REAR VIEW AWARDS 21X MULTI-PLATINUM ALBUM May // 5/1/18 - 5/31/18 FUTURE // EVOL PLATINUM ALBUM In May, RIAA certified 201 Song Awards and 37 Album Awards. All RIAA Awards dating back to 1958 are available at BLACK PANTHER THE ALBUM // SOUNDTRACK PLATINUM ALBUM riaa.com/gold-platinum! Don’t miss the NEW riaa.com/goldandplatinum60 site celebrating 60 years of Gold & Platinum CHARLIE PUTH // VOICENOTES GOLD ALBUM Awards and many #RIAATopCertified milestones for your favorite artists! LORDE // MELODRAMA SONGS GOLD ALBUM www.riaa.com // // // GOLD & PLATINUM AWARDS MAY // 5/1/18 - 5/31/18 MULTI PLATINUM SINGLE // 43 Cert Date// Title// Artist// Genre// Label// Plat Level// Rel. Date// R&B/ 5/22/2018 Bank Account 21 Savage Slaughter Gang/Epic 7/7/2017 Hip Hop Meant To Be (Feat. 5/25/2018 Bebe Rexha Pop Warner Bros Records 8/11/2017 Florida Georgia Line) 5/11/2018 Attention Charlie Puth Pop Atlantic Records 4/20/2017 R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records R&B/ Young Money/Cash Money/ 5/31/2018 God's Plan Drake 1/19/2018 Hip Hop Republic Records Crew (Feat. -

Sing Solo Pirate: Songs in the Key of Arrr! a Literature Guide for the Singer and Vocal Pedagogue

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music Music, School of 5-2013 Sing Solo Pirate: Songs in the Key of Arrr! A Literature Guide for the Singer and Vocal Pedagogue Michael S. Tully University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent Part of the Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Music Practice Commons Tully, Michael S., "Sing Solo Pirate: Songs in the Key of Arrr! A Literature Guide for the Singer and Vocal Pedagogue" (2013). Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music. 62. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/musicstudent/62 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Music, School of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Research, Creative Activity, and Performance - School of Music by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SING SOLO PIRATE: SONGS IN THE KEY OF ARRR! A LITERATURE GUIDE FOR THE SINGER AND VOCAL PEDAGOGUE by Michael S. Tully A DOCTORAL DOCUMENT Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Major: Music Under the Supervision of Professor William Shomos Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 SING SOLO PIRATE: SONGS IN THE KEY OF ARRR! A LITERATURE GUIDE FOR THE SINGER AND VOCAL PEDAGOGUE Michael S. Tully, D.M.A. University of Nebraska, 2013 Advisor: William Shomos Pirates have always been mysterious figures. -

Proquest Dissertations

READING, WRITING, AND RACIALIZATION: THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF BLACKNESS FOR STUDENTS AND EDUCATORS IN A PRINCE GEORGE'S COUNTY PUBLIC MIDDLE SCHOOL By Arvenita Washington Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of American University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy In Anthropology the ollege of Arts and Sciences ;;ia~~ Date 2008 American University Washington, D.C. 20016 AfvtERICAN UNIVERSffY LIBRARY ~ ~1,--1 UMI Number: 3340831 Copyright 2008 by Washington, Arvenita All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. ® UMI UM I M icroform 3340831 Copyright 2009 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway PO Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ©COPYRIGHT by Arvenita Washington 2008 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED I would like to dedicate this dissertation to my parents, my family, especially my Granny, and to all of my ancestors who paved a way in spite of oppression for me to have the opportunities I have and to exist in this moment. READING, WRITING, AND RACIALIZATION: THE SOCIAL CONSTRUCTION OF BLACKNESS FOR STUDENTS AND EDUCATORS IN A PRINCE GEORGE'S COUNTY PUBLIC MIDDLE SCHOOL BY Arvenita Washington ABSTRACT We do not fully understand how people of African descent, both in the United States and foreign born, conceptualize their integration into the predominantly "Black space" of Prince George's County or if and how the constituents of Black spaces are conceived of as diverse. -

Research Article COMBATING RACIAL STEREOTYPES THROUGH FILM

InternationalInternational journal Journal of ofResearch Recent and Advances Review in inHealth Multidisciplinary Sciences, July - 2014Research , February -2015 sZ International Journal of Recent Advances in Multidisciplinary Research Vol. 02, Issue 02, pp.0211-0218, February, 2015 Research Article COMBATING RACIAL STEREOTYPES THROUGH FILM: AN EXAMINATION OF STRATEGIES ADVANCED BY THE FILM “A DAY WITHOUT A MEXICAN” *Timothy E. Martin, Jr., Levi Pressnell, Daniel Turner, Terrence A. Merkerson and Andrew C. Kwon University of Alabama, US ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Article History: There are many diverging opinions on the issue of immigration and in 2012 one specific cultural group Received 27th November, 2014 received large attention within national media. One movie offers a portrayal of what life would be like Received in revised form in California if those of Hispanic ethnicity suddenly disappeared. Director Sergio Arau’s “A Day 05th December, 2014 without a Mexican” (2004) is a satirical comedy that seeks to demonstrate how important Hispanics are Accepted 09th January, 2015 to California. This movie intends to be comedic while conveying a persuasive message about the st Published online 28 February, 2015 important role of Hispanics in America. Although race in the media has been traditionally focused on escalating negative portrayals of various ethnic groups, there is an apparent trend in employing humor in Keywords: media to combat stereotypes and as a form of protest. This paper explores the types of rhetorical devices Race, and strategies the film “A Day without a Mexican” (2004) uses to combat race issues, confront Stereotypes, stereotypes, and then outlines the four main strategies discovered within the film.